Final 1998 Clean Air Plan Appendices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fy19-20 Low Carbon Transit Operations Program Allocation Award List

Caltrans-Division of Rail and Mass Transportation FY19-20 LOW CARBON TRANSIT OPERATIONS PROGRAM ALLOCATION AWARD LIST Disadvantaged Low 1/2 Mile Low- Community Income Income Buffer Total Project Project Benefit Benefit Benefit Request SB 1119 District Project ID Lead Agency: Project Name: Type: Project Description (Short): FY19-20 City of Arcata (Arcata Mad River Transit To allow Free Transit to encourage ridership on Arcata Mad River Transit NO YES NO #N/A 1 19-20-D01-001 System) AMRTS Free Fares Operations System $13,339 This project will provide reduced fares and free ticket vouchers to raise Humboldt Transit Reduced Fares and Free awareness of public transportation. This will give riders an opportunity to NO YES NO #N/A 1 19-20-D01-002 Authority Ticket Vouchers Operations try transit at no cost. $303,307 This project provides for the purchase and installation of a solar canopy to cover the bus parking lot. The canopy will provide enough electricity to power four electric buses and the operations facility. The canopy will also shade the lot, reducing the time buses are idling prior to inspection and NO YES NO #N/A 1 19-20-D01-003 Lake Transit Authority Solar Canopy Project Capital start-up. $102,736 The project will provide unlimited free use of Lake Transit Authority bus routes anywhere in Lake, Napa, or Mendocino counties for the following: Free Fares for Community (1) any Mendocino College or Woodland College student displaying a College Students and the valid student identification and (2) any child between the age of 7 and 17 NO YES NO #N/A 1 19-20-D01-004 Lake Transit Authority Summer Cruisin' Program Operations between June 15 and August 31 (known as the Summer Cruisin' Program) $23,351 RCTA will use LCTOP funding in a three-year bus electrification project, planning an installing an electric recharge facility and augmenting an FTA bus grant to purchase an electric powered vehicle. -

Capital Budget

REGULAR MEETING of the SANTA BARBARA METROPOLITAN TRANSIT DISTRICT BOARD OF DIRECTORS a Public Agency Tuesday, June 1, 2021 8:30 AM VIA TELECONFERENCE IMPORTANT NOTICE REGARDING THIS BOARD MEETING: This virtual meeting is being conducted utilizing teleconferencing and electronic means pursuant to State of California Executive Order N-29-20 issued by Governor Gavin Newsom on March 17, 2020, regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. The public may only view a livestream of the meeting online at: http://tinyurl.com/sbmtdyoutube Public Participation To make a general public comment or to comment on a specific agenda item, the following methods are available: Email, Phone, and Zoom webinar. All comments will be limited to 3 minutes per speaker. 1. Email: • Submit public comment to [email protected] before 12 p.m. on the Monday prior to the Board meeting for advance distribution to the Board of Directors. • Public comment emails submitted to [email protected] during the meeting will be recognized if the email is received prior to or during the item to be addressed. • In ALL emailed Public Comments, please include: (A) The agenda item(s) to be addressed (B) If you would like your comment read into the record (C) Public Comment text 2. Phone: Call the Zoom webinar line 10 minutes prior to the 8:30 a.m. meeting start time: • Toll-Free Dial-in: (669) 900-6833. • When prompted, enter Meeting ID 960 9033 4281 and then #. • When prompted for a password, dial 869064 and then #. • When the item you wish to address is announced, dial *9 to request to comment. -

VCTC Intercity Five-Year Service Plan Ventura County Transportation Commission

VENTURA COUNTY SHORT RANGE TRANSIT PLAN Ventura County Transportation Commission VCTC Intercity Five-Year Service Plan Ventura County Transportation Commission August 2015 VCTC INTERCITY – FIVE YEAR PLAN Ventura County Transportation Commission Table of Contents Page 1 Executive Summary .........................................................................................................1-1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1-1 Plan Development .................................................................................................................................. 1-1 2 Service Evaluation ...........................................................................................................2-1 Historical Trends ..................................................................................................................................... 2-1 Service Allocation .................................................................................................................................. 2-3 System Ridership Performance ............................................................................................................ 2-5 Route Profiles ........................................................................................................................................ 2-10 VCTC Intercity On-Board Survey Results ....................................................................................... -

DRAFT Service Implementation Plan

Task 4.4: DRAFT Service Implementation Plan SLOCOG Coast Rail Corridor Study March 26, 2021 In Association With: AMMA Transit Planning Verdin Marketing Coast Rail Corridor Study March 2021 Service Implementation Plan CONTENTS Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Stakeholder Engagement .......................................................................................................................... 2 Service Options ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Assessment of Service Options ................................................................................................................ 4 Governance ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Next Steps ................................................................................................................................................. 7 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Study Purpose ............................................................................................................................... 8 Study Need ................................................................................................................................... -

PLEASE NOTE: Credit Adjustment Processing Times for Eligible

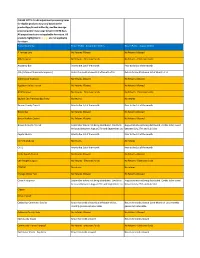

PLEASE NOTE: Credit adjustment processing times for eligible products may vary based on the product type/transit authority, and the average processing time may range between 60-90 days. All prepaid cards are not applicable for return. All products highlighted in orange are not applicable for return. Transit Authority Return Policy - September Orders Return Policy - August Orders A Yankee Line No Returns Allowed No Returns Allowed ABS Vanpool No Returns - Electronic funds No Returns - Electronic funds Academy Bus Prior to the 1st of the month Prior to the 1st of the month ACE (Altamont Commuter Express) Return for credit allowed 1st of Month of Us Return for credit allowed 1st of Month of Us Adirondack Trailways No Returns Allowed No Returns Allowed Appleton Valley Transit No Returns Allowed No Returns Allowed AVR Vanpool No Returns - Electronic funds No Returns - Electronic funds Baylink San Francisco Bay Ferry No returns No returns Beaver County Transit Prior to the 1st of the month Prior to the 1st of the month Bloom Bus No Returns Allowed No Returns Allowed Boston Harbor Cruises No Returns Allowed No Returns Allowed Broward County Transit September tickets not being distributed. Credits to August tickets not being distributed. Credits to be issued be issued between August 27th and September 1st. between July 27th and July 31st. Capital Metro Prior to the 1st of the month Prior to the 1st of the month CAT (Harrisburg) No returns No returns CATS Prior to the 1st of the month Prior to the 1st of the month Cedar Rapids Transit No Returns Allowed No Returns Allowed Cee People Buspool No Returns - Electronic funds No Returns - Electronic funds CENTRO No returns No returns Chicago Water Taxi No Returns Allowed No Returns Allowed Clean Air Express September tickets not being distributed. -

Intercommunity Transit Service

STAFF REPORT TO: TTAC, NCTAC, SBCTAC SUBJECT: Intercommunity Transit Service MEETING DATE: May 4, 2004 AGENDA ITEM: 4 RECOMMENDATION: A. Recommend approval of final draft Intercommunity Transit Service Implementation Plan between Lompoc – VAFB – Santa Maria. B. Recommend selection of lease/purchase budget scenario for development of CMAQ application. C. Review and comment on draft, Memorandum of Understanding, between the cities of Santa Maria, Lompoc, the County of Santa Barbara, and the Santa Barbara County Association of Governments, Regarding Coordination of a Three-Year Pilot Project to Provide Regular, Fixed Route, Commuter Public Transportation Service between Lompoc and Santa Maria. DISCUSSION: Background Last month staff obtained input from various advisory committees such as TTAC (Technical Transportation Advisory Committee) North County Transit Advisory Committee (NCTAC), and the Santa Barbara County Transit Advisory Council (SBCTAC) on the draft Transit Service Implementation Plan. The North County Transit Advisory Committee met on March 30 and approved the draft plan with the recommendation that a bus leasing option be given priority consideration so the service is delivered expeditiously. The Santa Barbara County Transit Advisory Council met later that same day and recommended that a leasing option be given priority consideration so the service is delivered expeditiously and that a low – floor bus configuration be selected to facilitate use of the service by disabled users. TTAC met on April 1 and requested the following adjustments to the assumptions in the development of the final plan: re-examine fuel costs due to recent increase in fuel price, assess implications of schedule on driver needs due to likelihood of split shifts increasing costs, delete Lakeview SB stop, add a formal annual evaluation period, at the end of two years assess continuation of service based on performance standards, and increase costs for comparable ADA transit service option. -

An Evaluation of California's Continuously Appropriated

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Projects Master's Theses and Graduate Research Fall 12-2019 An Evaluation of California’s Continuously Appropriated Programs Funded through Cap-and-Trade Domingo Candelas San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_projects Part of the Energy Policy Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Health Policy Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, Policy History, Theory, and Methods Commons, Public Administration Commons, and the Transportation Commons Recommended Citation Candelas, Domingo, "An Evaluation of California’s Continuously Appropriated Programs Funded through Cap-and-Trade" (2019). Master's Projects. 899. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.rjby-w76c https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_projects/899 This Master's Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Evaluation of California’s Continuously Appropriated Programs Funded through Cap-and-Trade By Domingo Candelas A Thesis Quality Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master’s Degree in PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION Frances Edwards, Ph.D. The Graduate School San Jose State University Fall 2019 CONTINUOUS APPROPRIATIONS IN CAP-AND-TRADE 2 Abstract In 2006, the State of California passed AB 32, the Global Warming Solutions Act (CARB, 2014). Through this legislation, the state sought to reduce its carbon emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. The California Air Resources Board (CARB) was tasked with doing so and thus instituted the Cap-and-Trade program, a market-based mechanism to reduce emissions. -

Transportation Emergency Preparedness Plan DRAFT | September 30, 2020 TABLE of CONTENTS

TRANSPORTATION EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS PLAN DRAFT Prepared for Prepared by Claris Strategy Terra Firma Enterprises CPARS Consulting SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 WARNING: FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Information contained in this document is exempt from FOIA (Exemption 2). Any authorized individual who knowingly or recklessly divulges information from this document may be imprisoned for one year, fined or both. This page intentionally left blank. 3 | Transportation Emergency Preparedness Plan DRAFT | September 30, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION 10 1.1 Foreword 10 1.2 How to use the TEPP 10 1.3 Planning Assumptions and Considerations 11 1.4 Purpose 11 1.5 Objectives 12 1.6 Scope and Applicability 12 1.7 Authorities, Requirements and Regulations 12 1.8 Approval and Promulgation 13 1.9 Maintenance of Plan 13 1.10 Public Awareness and Education 13 1.11 ADA Considerations 14 1.12 Training, Exercises and Improvement Plan 14 1.13 Distribution List / Department and Agency Concurrence 14 2.0 SECTION TWO: SANTA BARBARA AND VENTURA COUNTIES OVERVIEW 18 2.1 Transportation Infrastructure for Santa Barbara and Ventura Counties 20 2.2 Vulnerable Populations 31 2.3 Threat Summaries 33 2.4 Prioritization Of Threats That May Impact Transportation 44 3.0 SECTION THREE: CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS 48 3.1 Organization 48 3.2 Activation Procedures 55 3.3 Communications 62 3.4 Facilities 63 4.0 SECTION FOUR: ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES 66 4.1 Local and Regional Government Agencies 66 4.2 State Agencies 69 4.3 Federal Government 70 4.4 Multi-Agency Coordination -

Public Transportation Modernization, Improvement, and Service Enhancement Account Program Annual Legislative Report Fiscal Year 2017–18

Public Transportation Modernization, Improvement, and Service Enhancement Account Program Annual Legislative Report Fiscal Year 2017–18 Report to the Legislature 2018 [This page intentionally left blank.] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 2 Background ................................................................................................................................ 3 Statutory Reference and Purpose ........................................................................................ 3 Program Background ........................................................................................................... 3 Program Status/Program Accomplishments ............................................................................... 4 Intercity Rail Improvement Program Projects ........................................................................ 4-10 Table 1: Open Intercity Rail Improvement Program Projects ................................................ 8 Table 2: Completed/Closed Intercity Rail Improvement Program Projects ....................... 9-10 Mass Transportation Program Proposition 1B Bond Fund .........................................................10 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................11 Appendix A. Statutory Reporting Reference .............................................................................12 -

Transit Needs Assessment 2019

Transit Needs Assessment 2019 MARCH 2019 Transit Needs Assessment 2019 Project Staff Marjie Kirn Executive Director Michael Becker Director of Planning Jared Carvalho Transportation Planner Santa Barbara County Association of Governments 260 North San Antonio Road, Suite B Santa Barbara, CA, 93110 (805) 961-8900 www.sbcag.org Financial support for the preparation of this report was provided by the State of California. 2019 Membership Roster SUPERVISORS Member Supervisorial District DAS WILLIAMS FIRST DISTRICT GREGG HART (Vice Chair) SECOND DISTRICT JOAN HARTMANN THIRD DISTRICT PETER ADAM FOURTH DISTRICT STEVE LAVAGNINO FIFTH DISTRICT CITIES Member Alternate BUELLTON HOLLY SIERRA ED ANDRISEK Mayor Councilmember CARPINTERIA AL CLARK WADE NOMURA Councilmember Councilmember GOLETA PAULA PEROTTE STUART KASDIN Mayor Councilmember GUADALUPE ARISTON JULIAN GINA RUBALCABA Mayor Councilmember LOMPOC JAMES MOSBY JENELLE OSBORNE Councilmember Councilmember SANTA BARBARA CATHY MURILLO NONE Mayor SANTA MARIA ALICE PATINO (Chair) ETTA WATERFIELD Mayor Councilmember SOLVANG RYAN TOUSSAINT KAREN WAITE Mayor Councilmember EX-OFFICIO (NON-VOTING) MEMBERS CALTRANS DISTRICT 5 TIM GUBBINS 19th SENATE DISTRICT HANNAH BETH JACKSON 33rd ASSEMBLY DISTRICT JORDAN CUNNINGHAM 35th ASSEMBLY DISTRICT MONIQUE LIMON This page is intentionally left blank. With Special Recognition Santa Barbara County Transit Advisory Committee (SBCTAC) Representative of: Voting Member LOCAL SOCIAL SERVICE PROVIDERS FOR PERSONS Bleavins, Polly WITH DISABILITIES Children and Families Commission -

Item #11 May 11, 2018 MEMO TO: VENTURA COUNTY

VCTC - October 5, 2018, May 2018 Fare Equity Survey Item #12, Attachment A 1 of 90 Item #11 May 11, 2018 MEMO TO: VENTURA COUNTY TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION FROM: MARTIN R. ERICKSON, PUBLIC TRANSIT DIRECTOR SUBJECT: TITLE VI FARE EQUITY SURVEY RESULTS RECOMMENDATION: Receive a presentation on Title VI Fare Equity Survey results from Moore & Associates. Provide direction to staff to initiate the process for a fare increase, develop analysis of revenue and ridership impacts of a fare increase, and return to the Commission in June with alternatives. BACKGROUND: The Commission last approved a fare increase for VCTC Intercity transit service in November, 2010. Periodic evaluation of our fare structure is an industry best practice, and to this end, VCTC staff has been exploring fare restructuring options. Additionally, the Coastal Express Policy Committee, comprised of members for VCTC and SBCAG, has recommended a fare increase be brought to the full Commission. As such, current demographic and fare payment information is essential to ensure continued compliance with federal Title VI requirements. In 2017, VCTC retained Moore & Associates, Inc. to conduct onboard passenger surveys to compile passenger information regarding fare payment methods as well as demographic information in support of federal Title VI requirements. Survey objectives included: Identify passenger fare payment characteristics, including types of passes used; Develop passenger demographic profiles; Develop a profile of fare usage by minority and low-income individuals; and Identify trip characteristics. These objectives were reached through the systematic collection of a sufficient number of completed passenger surveys to allow assessments of rider demographics, fare usage patterns, and trip characteristics by route. -

Staff Report

STAFF REPORT SUBJECT: Transit Needs Assessment MEETING DATE: April 21, 2005 AGENDA ITEM: 8 RECOMMENDATION: Adopt a resolution approving unmet transit needs findings and consider approval of the 2005 Transit Needs Assessment Report SUMMARY: The annual Transit Needs Assessment process, as required by the state Transportation Development Act (TDA), requires SBCAG to adopt by resolution findings of “unmet needs” and “reasonable to meet”, for identified transit needs for jurisdictions which request LTF Article 8 funds to be used for the purpose of streets and roads. Those jurisdictions seeking the use of LTF Article 8 funds for streets and roads purposes are the cities of Lompoc and Santa Maria and northern Santa Barbara County. Because all LTF Article 8 funds in the South Coast are dedicated to transit, there are no findings of unmet need or reasonable to meet for South Coast transit needs identified through the public process. However, SBCAG does document and work with SBMTD to resolve these issues. A summary of the findings of unmet need and reasonable to meet is located on pages 10-13 and a summary of policy considerations is located on page 14 of this report. Transit services in the north county are continuing to improve with new intercommunity transit being initiated between Santa Maria, Vandenberg Air Force Base and Lompoc and expansion of services within the urbanized areas. Providing service that is cost effective and meets minimum farebox recovery requirements, however, is an ongoing challenge for north county transit operators. Based on the assessment documented in the report, it is recommended that the board find that there are no unmet transit needs that are reasonable to meet, beyond those that are being met through expanded services in FY 2005-06.