Plant Diversity Ecol 182 – 3-1-2007 Posted on Web – 2-28-07 at 5:30 Pm Summary from Last Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogenetic Classification of Life

Proc. Natl. Accad. Sci. USA Vol. 93, pp. 1071-1076, February 1996 Evolution Archaeal- eubacterial mergers in the origin of Eukarya: Phylogenetic classification of life (centriole-kinetosome DNA/Protoctista/kingdom classification/symbiogenesis/archaeprotist) LYNN MARGULIS Department of Biology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003-5810 Conitribluted by Lynnl Marglulis, September 15, 1995 ABSTRACT A symbiosis-based phylogeny leads to a con- these features evolved in their ancestors by inferable steps (4, sistent, useful classification system for all life. "Kingdoms" 20). rRNA gene sequences (Trichomonas, Coronympha, Giar- and "Domains" are replaced by biological names for the most dia; ref. 11) confirm these as descendants of anaerobic eu- inclusive taxa: Prokarya (bacteria) and Eukarya (symbiosis- karyotes that evolved prior to the "crown group" (12)-e.g., derived nucleated organisms). The earliest Eukarya, anaero- animals, fungi, or plants. bic mastigotes, hypothetically originated from permanent If eukaryotes began as motility symbioses between Ar- whole-cell fusion between members of Archaea (e.g., Thermo- chaea-e.g., Thermoplasma acidophilum-like and Eubacteria plasma-like organisms) and of Eubacteria (e.g., Spirochaeta- (Spirochaeta-, Spirosymplokos-, or Diplocalyx-like microbes; like organisms). Molecular biology, life-history, and fossil ref. 4) where cell-genetic integration led to the nucleus- record evidence support the reunification of bacteria as cytoskeletal system that defines eukaryotes (21)-then an Prokarya while -

Plant Evolution an Introduction to the History of Life

Plant Evolution An Introduction to the History of Life KARL J. NIKLAS The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction 1 1 Origins and Early Events 29 2 The Invasion of Land and Air 93 3 Population Genetics, Adaptation, and Evolution 153 4 Development and Evolution 217 5 Speciation and Microevolution 271 6 Macroevolution 325 7 The Evolution of Multicellularity 377 8 Biophysics and Evolution 431 9 Ecology and Evolution 483 Glossary 537 Index 547 v Introduction The unpredictable and the predetermined unfold together to make everything the way it is. It’s how nature creates itself, on every scale, the snowflake and the snowstorm. — TOM STOPPARD, Arcadia, Act 1, Scene 4 (1993) Much has been written about evolution from the perspective of the history and biology of animals, but significantly less has been writ- ten about the evolutionary biology of plants. Zoocentricism in the biological literature is understandable to some extent because we are after all animals and not plants and because our self- interest is not entirely egotistical, since no biologist can deny the fact that animals have played significant and important roles as the actors on the stage of evolution come and go. The nearly romantic fascination with di- nosaurs and what caused their extinction is understandable, even though we should be equally fascinated with the monarchs of the Carboniferous, the tree lycopods and calamites, and with what caused their extinction (fig. 0.1). Yet, it must be understood that plants are as fascinating as animals, and that they are just as important to the study of biology in general and to understanding evolutionary theory in particular. -

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

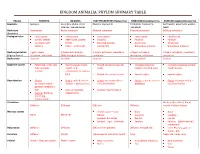

Kingdom Animalia: Phylum Summary Table

KINGDOM ANIMALIA: PHYLUM SUMMARY TABLE Phylum PORIFERA CNIDARIA PLATYHELMINTHES (flatworms) NEMATODA (roundworms) ANNELIDA (segmented worms) Examples Sponges Sea jellies, Hydra, coral Planaria, tapeworm Trichinella, hookworm, Earthworm, polychaete worms, colonies, sea anemones nematode leech Body type Asymmetry Radial symmetry Bilateral symmetry Bilateral symmetry Bilateral symmetry (Symmetry) Ecological roles Food source Food source Food source Food source Food source home / shelter Reef- home, protect Parasitic Parasitic Parasitic symbiotic with shores Eat dead animals – Aerate soil Aerate soil bacteria Chem. – anticancer saprophyte Breakdown material Breakdown material Body organization 2 germ layers 2 layers: ecto & endo 3 layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, 3 layers: ectoderm, 3 layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, (# germ layers) Ectoderm, endoderm With mesoglea between endoderm mesoderm, endoderm endoderm Body cavity Acoelom Acoelom Acoelom Pseudocoelom Coelom Digestive system Filter feed: collar cells, Gastrovascular cavity, Mouth and gastrovascular Complete digestive Complete digestive system: food vacuoles, mouth, and cavity system: mouth & anus mouth & anus osculum nematocysts to capture food Mouth also serves as anus Special organs Special organs Reproduction Sexual: Sexual: male & female Sexual: hermaphroditic – Sexual: separate sexes = Sexual: hermaphroditic – heramaphroditic – medusa – gametes fuse cross fertilization dioecious cross fertilization gametes released in H2O Asexual: budding, Asexual: fragmentation Asexual: budding, regeneration -

Chlorophyta Is a Division of Green Algae, Informally Called

Chlorophyta is a division of green algae, informally waters of the Sargasso Sea. Many brown algae, such as called chlorophytes. The name is used in two very members of the order Fucales, commonly grow along different senses so that care is needed to determine the rocky seashores. Some members of the class are used as use by a particular author. In older classification food for humans. systems, it refers to a highly paraphyletic group of all Worldwide there are about 1500–2000 species of brown the green algae within the green plants (Viridiplantae), algae.[4] Some species are of sufficient commercial and thus includes about 7,000 species [4] [5] of mostly importance, such as Ascophyllum nodosum , that they aquatic photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. Like the have become subjects of extensive research in their own land plants (bryophytes and tracheophytes), green algae right.[5] [4] contain chlorophylls a and b, and store food as starch Brown algae belong to a very large group, the in their plastids. Heterokontophyta, a eukaryotic group of organisms In newer classifications, it refers to one of the two distinguished most prominently by having chloroplasts clades making up the Viridiplantae, which are the surrounded by four membranes, suggesting an origin chlorophytes and the streptophytes or charophytes.[6][7] from a symbiotic relationship between a basal In this sense it includes only about 4,300 species.[3] eukaryote and another eukaryotic organism. Most brown algae contain the pigment fucoxanthin, which is responsible for the distinctive greenish-brown color that The red algae, or Rhodophyta ( / r o ʊ ˈ d ɒ f ɨ t ə / or / gives them their name. -

Fungi-Chapter 31 Refer to the Images of Life Cycles of Rhizopus, Morchella and Mushroom in Your Text Book and Lab Manual

Fungi-Chapter 31 Refer to the images of life cycles of Rhizopus, Morchella and Mushroom in your text book and lab manual. Chytrids Chytrids (phylum Chytridiomycota) are found in terrestrial, freshwater, and marine habitats including hydrothermal vents They can be decomposers, parasites, or mutualists Molecular evidence supports the hypothesis that chytrids diverged early in fungal evolution Chytrids are unique among fungi in having flagellated spores, called zoospores Zygomycetes The zygomycetes (phylum Zygomycota) exhibit great diversity of life histories They include fast-growing molds, parasites, and commensal symbionts The life cycle of black bread mold (Rhizopus stolonifer) is fairly typical of the phylum Its hyphae are coenocytic Asexual sporangia produce haploid spores The zygomycetes are named for their sexually produced zygosporangia Zygosporangia are the site of karyogamy and then meiosis Zygosporangia, which are resistant to freezing and drying, can survive unfavorable conditions Some zygomycetes, such as Pilobolus, can actually “aim” and shoot their sporangia toward bright light Glomeromycetes The glomeromycetes (phylum Glomeromycota) were once considered zygomycetes They are now classified in a separate clade Glomeromycetes form arbuscular mycorrhizae by growing into root cells but covered by host cell membrane. Ascomycetes Ascomycetes (phylum Ascomycota) live in marine, freshwater, and terrestrial habitats Ascomycetes produce sexual spores in saclike asci contained in fruiting bodies called ascocarps Ascomycetes are commonly -

Biology of Fungi, Lecture 2: the Diversity of Fungi and Fungus-Like Organisms

Biology of Fungi, Lecture 2: The Diversity of Fungi and Fungus-Like Organisms Terms You Should Understand u ‘Fungus’ (pl., fungi) is a taxonomic term and does not refer to morphology u ‘Mold’ is a morphological term referring to a filamentous (multicellular) condition u ‘Mildew’ is a term that refers to a particular type of mold u ‘Yeast’ is a morphological term referring to a unicellular condition Special Lecture Notes on Fungal Taxonomy u Fungal taxonomy is constantly in flux u Not one taxonomic scheme will be agreed upon by all mycologists u Classical fungal taxonomy was based primarily upon morphological features u Contemporary fungal taxonomy is based upon phylogenetic relationships Fungi in a Broad Sense u Mycologists have traditionally studied a diverse number of organisms, many not true fungi, but fungal-like in their appearance, physiology, or life style u At one point, these fungal-like microbes included the Actinomycetes, due to their filamentous growth patterns, but today are known as Gram-positive bacteria u The types of organisms mycologists have traditionally studied are now divided based upon phylogenetic relationships u These relationships are: Q Kingdom Fungi - true fungi Q Kingdom Straminipila - “water molds” Q Kingdom Mycetozoa - “slime molds” u Kingdom Fungi (Mycota) Q Phylum: Chytridiomycota Q Phylum: Zygomycota Q Phylum: Glomeromycota Q Phylum: Ascomycota Q Phylum: Basidiomycota Q Form-Phylum: Deuteromycota (Fungi Imperfecti) Page 1 of 16 Biology of Fungi Lecture 2: Diversity of Fungi u Kingdom Straminiplia (Chromista) -

Animal Phylum Poster Porifera

Phylum PORIFERA CNIDARIA PLATYHELMINTHES ANNELIDA MOLLUSCA ECHINODERMATA ARTHROPODA CHORDATA Hexactinellida -- glass (siliceous) Anthozoa -- corals and sea Turbellaria -- free-living or symbiotic Polychaetes -- segmented Gastopods -- snails and slugs Asteroidea -- starfish Trilobitomorpha -- tribolites (extinct) Urochordata -- tunicates Groups sponges anemones flatworms (Dugusia) bristleworms Bivalves -- clams, scallops, mussels Echinoidea -- sea urchins, sand Chelicerata Cephalochordata -- lancelets (organisms studied in detail in Demospongia -- spongin or Hydrazoa -- hydras, some corals Trematoda -- flukes (parasitic) Oligochaetes -- earthworms (Lumbricus) Cephalopods -- squid, octopus, dollars Arachnida -- spiders, scorpions Mixini -- hagfish siliceous sponges Xiphosura -- horseshoe crabs Bio1AL are underlined) Cubozoa -- box jellyfish, sea wasps Cestoda -- tapeworms (parasitic) Hirudinea -- leeches nautilus Holothuroidea -- sea cucumbers Petromyzontida -- lamprey Mandibulata Calcarea -- calcareous sponges Scyphozoa -- jellyfish, sea nettles Monogenea -- parasitic flatworms Polyplacophora -- chitons Ophiuroidea -- brittle stars Chondrichtyes -- sharks, skates Crustacea -- crustaceans (shrimp, crayfish Scleropongiae -- coralline or Crinoidea -- sea lily, feather stars Actinipterygia -- ray-finned fish tropical reef sponges Hexapoda -- insects (cockroach, fruit fly) Sarcopterygia -- lobed-finned fish Myriapoda Amphibia (frog, newt) Chilopoda -- centipedes Diplopoda -- millipedes Reptilia (snake, turtle) Aves (chicken, hummingbird) Mammalia -

Darwin's “Tree of Life”

Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education DARWIN’S “TREE OF LIFE” mon descent. Finally, he demands that text- books treat universal common ancestry as PHYLOGENETIC TREES unproven and refrain from illustrating that n biology, a phylogenetic tree, or phyloge- “theory” with misleading phylogenies. ny, is used to show the genealogic relation- Therefore, according to Wells, textbooks Iships of living things. A phylogeny is not should state that there is no evidence for com- so much evidence for evolution as much as it mon descent and that the most recent research is a codification of data about evolutionary his- refutes the concept entirely. Wells is complete- tory. According to biological evolution, organ- ly wrong on all counts, and his argument is isms share common ancestors; a phylogeny entirely based on misdirection and confusion. shows how organisms are related. The tree of He mixes up these various topics in order to life shows the path evolution took to get to the confuse the reader into thinking that when current diversity of life. It also shows that we combined, they show an endemic failure of can ascertain the genealogy of disparate living evolutionary theory. In effect, Wells plays the organisms. This is evidence for evolution only equivalent of an intellectual shell game, put- in that we can construct such trees at all. If ting so many topics into play that the “ball” of evolution had not happened or common ances- evolution gets lost. try were false, we would not be able to discov- THE CAMBRIAN EXPLOSION er hierarchical branching genealogies for ells claims that the Cambrian organisms (although textbooks do not general- Explosion “presents a serious chal- ly explain this well). -

New Phylogenomic Analysis of the Enigmatic Phylum Telonemia Further Resolves the Eukaryote Tree of Life

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/403329; this version posted August 30, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. New phylogenomic analysis of the enigmatic phylum Telonemia further resolves the eukaryote tree of life Jürgen F. H. Strassert1, Mahwash Jamy1, Alexander P. Mylnikov2, Denis V. Tikhonenkov2, Fabien Burki1,* 1Department of Organismal Biology, Program in Systematic Biology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden 2Institute for Biology of Inland Waters, Russian Academy of Sciences, Borok, Yaroslavl Region, Russia *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: TSAR, Telonemia, phylogenomics, eukaryotes, tree of life, protists bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/403329; this version posted August 30, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract The broad-scale tree of eukaryotes is constantly improving, but the evolutionary origin of several major groups remains unknown. Resolving the phylogenetic position of these ‘orphan’ groups is important, especially those that originated early in evolution, because they represent missing evolutionary links between established groups. Telonemia is one such orphan taxon for which little is known. The group is composed of molecularly diverse biflagellated protists, often prevalent although not abundant in aquatic environments. -

I Biology I Lecture Outline 9 Kingdom Protista

I Biology I Lecture Outline 9 Kingdom Protista References (Textbook - pages 373-392, Lab Manual - pages 95-115) Major Characteristics Algae 1. Cbaracteristics 2. Classification 3. Division Cblorophyta 4. Division Chrysophyta 5. Division Phaeopbyta 6. Division Rhodopbyta Protozoans 1. Characteristics 2. Classification 3. Class FlageUata 4. Class Sarcodina 5. Class Ciliata 6. Class Sporozoa I Biology I Lecture Notes 9 Kingdom Protista References (Textbook - pages 373-392, Lab Manual- pages 95-115) Major Characteristics I. Protists possess eukaryotic cells with well defined nuclei and organelles 2. Most are unicellular, however there are multi-cellularforms 3. They are diverse in their structure 4. They vary in size from microscope algae to kelp that can be over 100feet in length 5. They are diverse (like bacteria) in the way they meet their nutritional needs A . Some are photosynthetic like land plants - are autotrophic B. Some ingest theirfood like animals - heterotrophic by ingestion C. Some absorb theirfood like bacteria andfungi - heterotrophic by absorption D. One species - Euglena - is mixotrophic meaning that it is capable ofboth autotrophic and heterotrophic life styles. 6. Reproduction in Protists A. is usually asexual by mitosis B. sexual reproduction involves meiosis and spore formation and usualJy occurs only when environmental conditions are hostile C. spores are resistant and can withstand adverse conditions 7. Some protozoans form cysts - a type ofresting stage 8. Photosynthetic protists (mostly algae) are part ofplankton. Plankton are those organisms suspended infresh and marine waters that serve asfood for -- heterotrophic animals and other protists 9. There are diverse opinions on how to classify members ofthe Kingdom Protista. -

The Wide World of Plants

11 The Wide World of Plants With so many different plants in the world, it’s tough to keep them all straight. But there are certain features we can see in plants that allow us to put them into helpful categories. Recommended Reading Plants: Flower Plants, Ferns, Mosses, and Other Plants, by Shar Levine and Leslie John- stone (Note: The intro to chapters 4 and 5 refer to the earth being over 100 million years old.) The Tree Book: For Kids and their Grown Ups,by Gina Ingoglia, p. 26-89 (Note: Fantastic resource for identifying trees during this week’s activity.) Nature Walk — Exploring ACTIVITY Plants Now that you know a little bit more about the different divisions of plants, take some time to get outdoors and explore plants this week! SUPPLY LIST INSTRUCTIONS • Copies of Exploring 1. Walk around outside and try to find examples of plants that are in the Plants: Observation four different divisions of plants we discussed in plants: Journal page Phylum Bryophyta, the mosses • Pencil Phylum Pterophyta, the ferns Phylum Coniferophyta, the cone-bearing plants Phylum Anthophyta, the flowering plants 2. Try to find at least one to two different examples of each category of plant you can sketch on the Exploring Plants: Observation Journal page. 3. See if you can identify the species of the plant — use a book or online resource to help you out! Reminder! Be sure to continue caring for and monitoring your bean plant. How is it doing? Take the time to sketch what it looks like and record its height.