Phylogenetic Classification of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexual Selection in Fungi

Sexual selection in Fungi Bart P. S. Nieuwenhuis Thesis committee Thesis supervisor Prof. dr. R.F. Hoekstra Emeritus professor of Genetics (Population and Quantitative Genetics) Wageningen University Thesis co-supervisor Dr. D.K. Aanen Assistant professor at the Laboratory of Genetics Wageningen University Other members Prof. dr. J. B. Anderson, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada Prof. dr. W. de Boer, NIOO, Wageningen and Wageningen University Prof. dr. P.G.L. Klinkhamer, Leiden University, Leiden Prof. dr. H.A.B. Wösten, Utrecht Univesity, Utrecht This research was conducted under the auspices of the C.T. de Wit Graduate School for Production Ecology and Resource Conservation (PE&RC) Sexual selection in Fungi Bart P. S. Nieuwenhuis Thesis submittted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. dr. M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Friday 21 September 2012 at 4 p.m. in the Aula. Bart P. S. Nieuwenhuis Sexual selection in Fungi Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2012) With references, with summaries in Dutch and English ISBN 978-94-6173-358-0 Contents Chapter 1 7 General introduction Chapter 2 17 Why mating types are not sexes Chapter 3 31 On the asymmetry of mating in the mushroom fungus Schizophyllum commune Chapter 4 49 Sexual selection in mushroom-forming basidiomycetes Chapter 5 59 Fungal fidelity: Nuclear divorce from a dikaryon by mating or monokaryon regeneration Chapter 6 69 Fungal nuclear arms race: experimental evolution for increased masculinity in a mushroom Chapter 7 89 Sexual selection in the fungal kingdom Chapter 8 109 Discussion: male and female fitness Bibliography 121 Summary 133 Dutch summary 137 Dankwoord 147 Curriculum vitea 153 Education statement 155 6 Chapter 1 General introduction Bart P. -

Why Mushrooms Have Evolved to Be So Promiscuous: Insights from Evolutionary and Ecological Patterns

fungal biology reviews 29 (2015) 167e178 journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fbr Review Why mushrooms have evolved to be so promiscuous: Insights from evolutionary and ecological patterns Timothy Y. JAMES* Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA article info abstract Article history: Agaricomycetes, the mushrooms, are considered to have a promiscuous mating system, Received 27 May 2015 because most populations have a large number of mating types. This diversity of mating Received in revised form types ensures a high outcrossing efficiency, the probability of encountering a compatible 17 October 2015 mate when mating at random, because nearly every homokaryotic genotype is compatible Accepted 23 October 2015 with every other. Here I summarize the data from mating type surveys and genetic analysis of mating type loci and ask what evolutionary and ecological factors have promoted pro- Keywords: miscuity. Outcrossing efficiency is equally high in both bipolar and tetrapolar species Genomic conflict with a median value of 0.967 in Agaricomycetes. The sessile nature of the homokaryotic Homeodomain mycelium coupled with frequent long distance dispersal could account for selection favor- Outbreeding potential ing a high outcrossing efficiency as opportunities for choosing mates may be minimal. Pheromone receptor Consistent with a role of mating type in mediating cytoplasmic-nuclear genomic conflict, Agaricomycetes have evolved away from a haploid yeast phase towards hyphal fusions that display reciprocal nuclear migration after mating rather than cytoplasmic fusion. Importantly, the evolution of this mating behavior is precisely timed with the onset of diversification of mating type alleles at the pheromone/receptor mating type loci that are known to control reciprocal nuclear migration during mating. -

Genome Sequence of the Hyperthermophilic Crenarchaeon Pyrobaculum Aerophilum

Genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic crenarchaeon Pyrobaculum aerophilum Sorel T. Fitz-Gibbon*†, Heidi Ladner*‡, Ung-Jin Kim§, Karl O. Stetter¶, Melvin I. Simon§, and Jeffrey H. Miller*ʈ *Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Genetics, and Molecular Biology Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1489; †IGPP Center for Astrobiology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1567; §Division of Biology, 147-75, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125; and ¶Archaeenzentrum, Regensburg University, 93053 Regensburg, Germany Contributed by Melvin I. Simon, November 30, 2001 We determined and annotated the complete 2.2-megabase genome sequence of Pyrobaculum aerophilum, a facultatively aerobic nitrate- C) crenarchaeon. Clues were°100 ؍ reducing hyperthermophilic (Topt found suggesting explanations of the organism’s surprising intoler- ance to sulfur, which may aid in the development of methods for genetic studies of the organism. Many interesting features worthy of further genetic studies were revealed. Whole genome computational analysis confirmed experiments showing that P. aerophilum (and perhaps all crenarchaea) lack 5 untranslated regions in their mRNAs and thus appear not to use a ribosome-binding site (Shine–Dalgarno)- .based mechanism for translation initiation at the 5 end of transcripts Inspection of the lengths and distribution of mononucleotide repeat- tracts revealed some interesting features. For instance, it was seen that mononucleotide repeat-tracts of Gs (or Cs) are highly unstable, a pattern expected for an organism deficient in mismatch repair. This result, together with an independent study on mutation rates, sug- gests a ‘‘mutator’’ phenotype. ϭ yrobaculum aerophilum is a hyperthermophilic (Tmax 104°C, Fig. 1. Small subunit rRNA-based phylogenetic tree of the crenarchaea. -

By Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

COMPARATIVE ANATOMY AND HISTOCHEMISTRY OF TIIE ASSOCIATION OF PUCCIiVIA POARUM WITH ITS ALTERNATE HOSTS By TALIB aWAID AL-KHESRAJI Department of Botany~ Universiiy of SheffieZd Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy JUNE 1981 Vol 1 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, lS23 7BQ www.bl.uk BEST COpy AVAILABLE. VARIABLE PRINT QUALITY TO MY PARENTS i Ca.1PARATIVE ANATCl1Y AND HISTOCHEMISTRY OF THE ASSOCIATION OF PUCCINIA POARUM WITH ITS ALTERNATE HOSTS Talib Owaid Al-Khesraji Depaptment of Botany, Univepsity of Sheffield The relationship of the macrocyclic rust fungus PUccinia poarum with its pycnial-aecial host, Tussilago fapfaPa, and its uredial-telial host, Poa ppatensis, has been investigated, using light microscopy, electron microscopy and micro-autoradiography. Aspects of the morp hology and ontogeny of spores and sari, which were previously disputed, have been clarified. Monokaryotic hyphae grow more densely in the intercellular spaces of Tussilago leaves than the dikaryotic intercellular hyphae on Poa. Although ultrastructurally sbnilar, monokaryotic hyphae differ from dikaryotic hyphae in their interaction with host cell walls, often growing embedded in wall material which may project into the host cells. The frequency of penetration of Poa mesophyll cells by haustoria of the dikaryon is greater than that of Tussilago cells by the relatively undifferentiated intracellular hyphae of the monokaryon. Intracellular hyphae differ from haustoria in their irregular growth, septation, lack of a neck-band or markedly constricted neck, the deposition of host wall-like material in the external matrix bounded by the invaginated host plasmalemma and in the association of callose reactions \vith intracellular hyphae and adjacent parts of host walls. -

Plant Evolution an Introduction to the History of Life

Plant Evolution An Introduction to the History of Life KARL J. NIKLAS The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction 1 1 Origins and Early Events 29 2 The Invasion of Land and Air 93 3 Population Genetics, Adaptation, and Evolution 153 4 Development and Evolution 217 5 Speciation and Microevolution 271 6 Macroevolution 325 7 The Evolution of Multicellularity 377 8 Biophysics and Evolution 431 9 Ecology and Evolution 483 Glossary 537 Index 547 v Introduction The unpredictable and the predetermined unfold together to make everything the way it is. It’s how nature creates itself, on every scale, the snowflake and the snowstorm. — TOM STOPPARD, Arcadia, Act 1, Scene 4 (1993) Much has been written about evolution from the perspective of the history and biology of animals, but significantly less has been writ- ten about the evolutionary biology of plants. Zoocentricism in the biological literature is understandable to some extent because we are after all animals and not plants and because our self- interest is not entirely egotistical, since no biologist can deny the fact that animals have played significant and important roles as the actors on the stage of evolution come and go. The nearly romantic fascination with di- nosaurs and what caused their extinction is understandable, even though we should be equally fascinated with the monarchs of the Carboniferous, the tree lycopods and calamites, and with what caused their extinction (fig. 0.1). Yet, it must be understood that plants are as fascinating as animals, and that they are just as important to the study of biology in general and to understanding evolutionary theory in particular. -

Classifications of Fungi

Chapter 24 | Fungi 675 Sexual Reproduction Sexual reproduction introduces genetic variation into a population of fungi. In fungi, sexual reproduction often occurs in response to adverse environmental conditions. During sexual reproduction, two mating types are produced. When both mating types are present in the same mycelium, it is called homothallic, or self-fertile. Heterothallic mycelia require two different, but compatible, mycelia to reproduce sexually. Although there are many variations in fungal sexual reproduction, all include the following three stages (Figure 24.8). First, during plasmogamy (literally, “marriage or union of cytoplasm”), two haploid cells fuse, leading to a dikaryotic stage where two haploid nuclei coexist in a single cell. During karyogamy (“nuclear marriage”), the haploid nuclei fuse to form a diploid zygote nucleus. Finally, meiosis takes place in the gametangia (singular, gametangium) organs, in which gametes of different mating types are generated. At this stage, spores are disseminated into the environment. Review the characteristics of fungi by visiting this interactive site (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/ fungi_kingdom) from Wisconsin-online. 24.2 | Classifications of Fungi By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following: • Identify fungi and place them into the five major phyla according to current classification • Describe each phylum in terms of major representative species and patterns of reproduction The kingdom Fungi contains five major phyla that were established according to their mode of sexual reproduction or using molecular data. Polyphyletic, unrelated fungi that reproduce without a sexual cycle, were once placed for convenience in a sixth group, the Deuteromycota, called a “form phylum,” because superficially they appeared to be similar. -

Displacement of the Canonical Single-Stranded DNA-Binding Protein in the Thermoproteales

Displacement of the canonical single-stranded DNA-binding protein in the Thermoproteales Sonia Paytubia,1,2, Stephen A. McMahona,2, Shirley Grahama, Huanting Liua, Catherine H. Bottinga, Kira S. Makarovab, Eugene V. Kooninb, James H. Naismitha,3, and Malcolm F. Whitea,3 aBiomedical Sciences Research Complex, University of St Andrews, Fife KY16 9ST, United Kingdom; and bNational Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20894 AUTHOR SUMMARY Proteins are the major structural and biochemical route involved direct puri- operational components of cells. Even fication and identification of proteins the simplest organisms possess hundreds thatcouldbindtossDNAinoneofthe of different proteins, and more complex Thermoproteales, Thermoproteus tenax. organisms typically have many thou- This approach resulted in the identifi- sands. Because all living beings, from cation of the product of the gene ttx1576 microbes to humans, are related by as a candidate for the missing SSB. evolution, they share a core set of pro- We proceeded to characterize the teins in common. Proteins perform properties of the Ttx1576 protein, (which fundamental roles in key metabolic we renamed “ThermoDBP” for Ther- processes and in the processing of in- moproteales DNA-binding protein), formation from DNA via RNA to pro- showing that it has all the biochemical teins. A notable example is the ssDNA- properties consistent with a role as a binding protein, SSB, which is essential functional SSB, including a clear prefer- for DNA replication and repair and is ence for ssDNA binding and low se- widely considered to be one of the quence specificity. Using crystallographic few core universal proteins shared by analysis, we solved the structure of the alllifeforms.Herewedemonstrate Fig. -

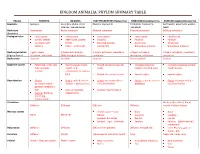

Kingdom Animalia: Phylum Summary Table

KINGDOM ANIMALIA: PHYLUM SUMMARY TABLE Phylum PORIFERA CNIDARIA PLATYHELMINTHES (flatworms) NEMATODA (roundworms) ANNELIDA (segmented worms) Examples Sponges Sea jellies, Hydra, coral Planaria, tapeworm Trichinella, hookworm, Earthworm, polychaete worms, colonies, sea anemones nematode leech Body type Asymmetry Radial symmetry Bilateral symmetry Bilateral symmetry Bilateral symmetry (Symmetry) Ecological roles Food source Food source Food source Food source Food source home / shelter Reef- home, protect Parasitic Parasitic Parasitic symbiotic with shores Eat dead animals – Aerate soil Aerate soil bacteria Chem. – anticancer saprophyte Breakdown material Breakdown material Body organization 2 germ layers 2 layers: ecto & endo 3 layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, 3 layers: ectoderm, 3 layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, (# germ layers) Ectoderm, endoderm With mesoglea between endoderm mesoderm, endoderm endoderm Body cavity Acoelom Acoelom Acoelom Pseudocoelom Coelom Digestive system Filter feed: collar cells, Gastrovascular cavity, Mouth and gastrovascular Complete digestive Complete digestive system: food vacuoles, mouth, and cavity system: mouth & anus mouth & anus osculum nematocysts to capture food Mouth also serves as anus Special organs Special organs Reproduction Sexual: Sexual: male & female Sexual: hermaphroditic – Sexual: separate sexes = Sexual: hermaphroditic – heramaphroditic – medusa – gametes fuse cross fertilization dioecious cross fertilization gametes released in H2O Asexual: budding, Asexual: fragmentation Asexual: budding, regeneration -

Fungi-Chapter 31 Refer to the Images of Life Cycles of Rhizopus, Morchella and Mushroom in Your Text Book and Lab Manual

Fungi-Chapter 31 Refer to the images of life cycles of Rhizopus, Morchella and Mushroom in your text book and lab manual. Chytrids Chytrids (phylum Chytridiomycota) are found in terrestrial, freshwater, and marine habitats including hydrothermal vents They can be decomposers, parasites, or mutualists Molecular evidence supports the hypothesis that chytrids diverged early in fungal evolution Chytrids are unique among fungi in having flagellated spores, called zoospores Zygomycetes The zygomycetes (phylum Zygomycota) exhibit great diversity of life histories They include fast-growing molds, parasites, and commensal symbionts The life cycle of black bread mold (Rhizopus stolonifer) is fairly typical of the phylum Its hyphae are coenocytic Asexual sporangia produce haploid spores The zygomycetes are named for their sexually produced zygosporangia Zygosporangia are the site of karyogamy and then meiosis Zygosporangia, which are resistant to freezing and drying, can survive unfavorable conditions Some zygomycetes, such as Pilobolus, can actually “aim” and shoot their sporangia toward bright light Glomeromycetes The glomeromycetes (phylum Glomeromycota) were once considered zygomycetes They are now classified in a separate clade Glomeromycetes form arbuscular mycorrhizae by growing into root cells but covered by host cell membrane. Ascomycetes Ascomycetes (phylum Ascomycota) live in marine, freshwater, and terrestrial habitats Ascomycetes produce sexual spores in saclike asci contained in fruiting bodies called ascocarps Ascomycetes are commonly -

Pyrobaculum Igneiluti Sp. Nov., a Novel Anaerobic Hyperthermophilic Archaeon That Reduces Thiosulfate and Ferric Iron

TAXONOMIC DESCRIPTION Lee et al., Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2017;67:1714–1719 DOI 10.1099/ijsem.0.001850 Pyrobaculum igneiluti sp. nov., a novel anaerobic hyperthermophilic archaeon that reduces thiosulfate and ferric iron Jerry Y. Lee, Brenda Iglesias, Caleb E. Chu, Daniel J. P. Lawrence and Edward Jerome Crane III* Abstract A novel anaerobic, hyperthermophilic archaeon was isolated from a mud volcano in the Salton Sea geothermal system in southern California, USA. The isolate, named strain 521T, grew optimally at 90 C, at pH 5.5–7.3 and with 0–2.0 % (w/v) NaCl, with a generation time of 10 h under optimal conditions. Cells were rod-shaped and non-motile, ranging from 2 to 7 μm in length. Strain 521T grew only in the presence of thiosulfate and/or Fe(III) (ferrihydrite) as terminal electron acceptors under strictly anaerobic conditions, and preferred protein-rich compounds as energy sources, although the isolate was capable of chemolithoautotrophic growth. 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis places this isolate within the crenarchaeal genus Pyrobaculum. To our knowledge, this is the first Pyrobaculum strain to be isolated from an anaerobic mud volcano and to reduce only either thiosulfate or ferric iron. An in silico genome-to-genome distance calculator reported <25 % DNA–DNA hybridization between strain 521T and eight other Pyrobaculum species. Due to its genotypic and phenotypic differences, we conclude that strain 521T represents a novel species, for which the name Pyrobaculum igneiluti sp. nov. is proposed. The type strain is 521T (=DSM 103086T=ATCC TSD-56T). Anaerobic respiratory processes based on the reduction of recently revealed by the receding of the Salton Sea, ejects sulfur compounds or Fe(III) have been proposed to be fluid of a similar composition at 90–95 C. -

Differences in Lateral Gene Transfer in Hypersaline Versus Thermal Environments Matthew E Rhodes1*, John R Spear2, Aharon Oren3 and Christopher H House1

Rhodes et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2011, 11:199 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/11/199 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Differences in lateral gene transfer in hypersaline versus thermal environments Matthew E Rhodes1*, John R Spear2, Aharon Oren3 and Christopher H House1 Abstract Background: The role of lateral gene transfer (LGT) in the evolution of microorganisms is only beginning to be understood. While most LGT events occur between closely related individuals, inter-phylum and inter-domain LGT events are not uncommon. These distant transfer events offer potentially greater fitness advantages and it is for this reason that these “long distance” LGT events may have significantly impacted the evolution of microbes. One mechanism driving distant LGT events is microbial transformation. Theoretically, transformative events can occur between any two species provided that the DNA of one enters the habitat of the other. Two categories of microorganisms that are well-known for LGT are the thermophiles and halophiles. Results: We identified potential inter-class LGT events into both a thermophilic class of Archaea (Thermoprotei) and a halophilic class of Archaea (Halobacteria). We then categorized these LGT genes as originating in thermophiles and halophiles respectively. While more than 68% of transfer events into Thermoprotei taxa originated in other thermophiles, less than 11% of transfer events into Halobacteria taxa originated in other halophiles. Conclusions: Our results suggest that there is a fundamental difference between LGT in thermophiles and halophiles. We theorize that the difference lies in the different natures of the environments. While DNA degrades rapidly in thermal environments due to temperature-driven denaturization, hypersaline environments are adept at preserving DNA. -

Biology of Fungi, Lecture 2: the Diversity of Fungi and Fungus-Like Organisms

Biology of Fungi, Lecture 2: The Diversity of Fungi and Fungus-Like Organisms Terms You Should Understand u ‘Fungus’ (pl., fungi) is a taxonomic term and does not refer to morphology u ‘Mold’ is a morphological term referring to a filamentous (multicellular) condition u ‘Mildew’ is a term that refers to a particular type of mold u ‘Yeast’ is a morphological term referring to a unicellular condition Special Lecture Notes on Fungal Taxonomy u Fungal taxonomy is constantly in flux u Not one taxonomic scheme will be agreed upon by all mycologists u Classical fungal taxonomy was based primarily upon morphological features u Contemporary fungal taxonomy is based upon phylogenetic relationships Fungi in a Broad Sense u Mycologists have traditionally studied a diverse number of organisms, many not true fungi, but fungal-like in their appearance, physiology, or life style u At one point, these fungal-like microbes included the Actinomycetes, due to their filamentous growth patterns, but today are known as Gram-positive bacteria u The types of organisms mycologists have traditionally studied are now divided based upon phylogenetic relationships u These relationships are: Q Kingdom Fungi - true fungi Q Kingdom Straminipila - “water molds” Q Kingdom Mycetozoa - “slime molds” u Kingdom Fungi (Mycota) Q Phylum: Chytridiomycota Q Phylum: Zygomycota Q Phylum: Glomeromycota Q Phylum: Ascomycota Q Phylum: Basidiomycota Q Form-Phylum: Deuteromycota (Fungi Imperfecti) Page 1 of 16 Biology of Fungi Lecture 2: Diversity of Fungi u Kingdom Straminiplia (Chromista)