Plant Evolution an Introduction to the History of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 20 - the History of Life on Earth

Lecture 20 - The History of Life on Earth Lecture 20 The History of Life on Earth Astronomy 141 – Autumn 2012 This lecture reviews the history of life on Earth. Rapid diversification of anaerobic prokaryotes during the Proterozoic Eon Emergence of Photosynthesis and the rise of O2 in the Earth’s atmosphere. Rise of Eukaryotes and the Cambrian Explosion in biodiversity at the start of the Phanerozoic Eon Colonization of land first by plants, then by animals Emergence of primates, then hominids, then humans. A brief digression on notation: “ya” = “years ago” Introduce a simple compact notation for writing the length of time before the present day. For example: “3.5 Billion years ago” “454 Million years ago” Gya = “giga-years ago”, hence 3.5 Gya = 3.5 Billion years ago Mya = “mega-years ago”, hence 454 Mya = 454 Million years ago [Note: some sources use Ga and Ma] Astronomy 141 - Winter 2012 1 Lecture 20 - The History of Life on Earth The four Eons of geological time. Hadean: 4.5 – 3.8 Gya: Formation, oceans & atmosphere Archaean: 3.8 – 2.5 Gya: Stromatolites & fossil bacteria Proterozoic: 2.5 Gya – 454 Mya: Eukarya and Oxygen Phanerozoic: since 454 Mya: Rise of plant and animal life The Archaean Eon began with the end of heavy bombardment ~3.8 Gya. Conditions stabilized. Oceans, but no O2 in the atmosphere. Stromatolites appear in the geological record ~3.5 Gya and thrived for >1 Billion years Rise of anaerobic microbes in the deep ocean & shores using Chemosynthesis. Time of rapid diversification of life driven by Natural Selection. -

Buzzle – Zoology Terms – Glossary of Biology Terms and Definitions Http

Buzzle – Zoology Terms – Glossary of Biology Terms and Definitions http://www.buzzle.com/articles/biology-terms-glossary-of-biology-terms-and- definitions.html#ZoologyGlossary Biology is the branch of science concerned with the study of life: structure, growth, functioning and evolution of living things. This discipline of science comprises three sub-disciplines that are botany (study of plants), Zoology (study of animals) and Microbiology (study of microorganisms). This vast subject of science involves the usage of myriads of biology terms, which are essential to be comprehended correctly. People involved in the science field encounter innumerable jargons during their study, research or work. Moreover, since science is a part of everybody's life, it is something that is important to all individuals. A Abdomen: Abdomen in mammals is the portion of the body which is located below the rib cage, and in arthropods below the thorax. It is the cavity that contains stomach, intestines, etc. Abscission: Abscission is a process of shedding or separating part of an organism from the rest of it. Common examples are that of, plant parts like leaves, fruits, flowers and bark being separated from the plant. Accidental: Accidental refers to the occurrences or existence of all those species that would not be found in a particular region under normal circumstances. Acclimation: Acclimation refers to the morphological and/or physiological changes experienced by various organisms to adapt or accustom themselves to a new climate or environment. Active Transport: The movement of cellular substances like ions or molecules by traveling across the membrane, towards a higher level of concentration while consuming energy. -

The Chloroplast Rpl23 Gene Cluster of Spirogyra Maxima (Charophyceae) Shares Many Similarities with the Angiosperm Rpl23 Operon

Algae Volume 17(1): 59-68, 2002 The Chloroplast rpl23 Gene Cluster of Spirogyra maxima (Charophyceae) Shares Many Similarities with the Angiosperm rpl23 Operon Jungho Lee* and James R. Manhart Department of Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, 77843-3258, U.S.A. A phylogenetic affinity between charophytes and embryophytes (land plants) has been explained by a few chloro- plast genomic characters including gene and intron (Manhart and Palmer 1990; Baldauf et al. 1990; Lew and Manhart 1993). Here we show that a charophyte, Spirogyra maxima, has the largest operon of angiosperm chloroplast genomes, rpl23 operon (trnI-rpl23-rpl2-rps19-rpl22-rps3-rpl16-rpl14-rps8-infA-rpl36-rps11-rpoA) containing both embryophyte introns, rpl16.i and rpl2.i. The rpl23 gene cluster of Spirogyra contains a distinct eubacterial promoter sequence upstream of rpl23, which is the first gene of the green algal rpl23 gene cluster. This sequence is completely absent in angiosperms but is present in non-flowering plants. The results imply that, in the rpl23 gene cluster, early charophytes had at least two promoters, one upstream of trnI and another upstream of rpl23, which partially or completely lost its function in land plants. A comparison of gene clusters of prokaryotes, algal chloroplast DNAs and land plant cpDNAs indicated a loss of numerous genes in chlorophyll a+b eukaryotes. A phylogenetic analysis using presence/absence of genes and introns as characters produced trees with a strongly supported clade contain- ing chlorophyll a+b eukaryotes. Spirogyra and embryophytes formed a clade characterized by the loss of rpl5 and rps9 and the gain of trnI (CAU) and introns in rpl2 and rpl16. -

Chapter 22 Notes: Introduction to Evolution

NOTES: Ch 22 – Descent With Modification – A Darwinian View of Life Our planet is home to a huge variety of organisms! (Scientists estimate of organisms alive today!) Even more amazing is evidence of organisms that once lived on earth, but are now . Several hundred million species have come and gone during 4.5 billion years life is believed to have existed on earth So…where have they gone… why have they disappeared? EVOLUTION: the process by which have descended from . Central Idea: organisms alive today have been produced by a long process of . FITNESS: refers to traits and behaviors of organisms that enable them to survive and reproduce COMMON DESCENT: species ADAPTATION: any inherited characteristic that enhances an organism’s ability to ~based on variations that are HOW DO WE KNOW THAT EVOLUTION HAS OCCURRED (and is still happening!!!)??? Lines of evidence: 1) So many species! -at least (250,000 beetles!) 2) ADAPTATIONS ● Structural adaptations - - ● Physiological adaptations -change in - to certain toxins 3) Biogeography: - - and -Examples: 13 species of finches on the 13 Galapagos Islands -57 species of Kangaroos…all in Australia 4) Age of Earth: -Rates of motion of tectonic plates - 5) FOSSILS: -Evidence of (shells, casts, bones, teeth, imprints) -Show a -We see progressive changes based on the order they were buried in sedimentary rock: *Few many fossils / species * 6) Applied Genetics: “Artificial Selection” - (cattle, dogs, cats) -insecticide-resistant insects - 7) Homologies: resulting from common ancestry Anatomical Homologies: ● comparative anatomy reveals HOMOLOGOUS STRUCTURES ( , different functions) -EX: ! Vestigial Organs: -“Leftovers” from the evolutionary past -Structures that Embryological Homologies: ● similarities evident in Molecular/Biochemical Homologies: ● DNA is the “universal” genetic code or code of life ● Proteins ( ) Darwin & the Scientists of his time Introduction to Darwin… ● On November 24, 1859, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. -

Random Mutation and Natural Selection in Competitive and Non-Competitive Environments

ISSN: 2574-1241 Volume 5- Issue 4: 2018 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.09.001751 Alan Kleinman. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res Mini Review Open Access Random Mutation and Natural Selection In Competitive and Non-Competitive Environments Alan Kleinman* Department of Medicine, USA Received: : September 10, 2018; Published: September 18, 2018 *Corresponding author: Alan Kleinman, PO BOX 1240, Coarsegold, CA 93614, USA Abstract Random mutation and natural selection occur in a variety of different environments. Three of the most important factors which govern the rate at which this phenomenon occurs is whether there is competition between the different variants for the resources of the environment or not whether the replicator can do recombination and whether the intensity of selection has an impact on the evolutionary trajectory. Two different experimental models of random mutation and natural selection are analyzed to determine the impact of competition on random mutation and natural selection. One experiment places the different variants in competition for the resources of the environment while the lineages are attempting to evolve to the selection pressure while the other experiment allows the lineages to grow without intense competition for the resources of the environment while the different lineages are attempting to evolve to the selection pressure. The mathematics which governs either experiment is discussed, and the results correlated to the medical problem of the evolution of drug resistance. Introduction important experiments testing the RMNS phenomenon. And how Random mutation and natural selection (RMNS) are a does recombination alter the evolutionary trajectory to a given phenomenon which works to defeat the treatments physicians use selection pressure? for infectious diseases and cancers. -

Timeline of the Evolutionary History of Life

Timeline of the evolutionary history of life This timeline of the evolutionary history of life represents the current scientific theory Life timeline Ice Ages outlining the major events during the 0 — Primates Quater nary Flowers ←Earliest apes development of life on planet Earth. In P Birds h Mammals – Plants Dinosaurs biology, evolution is any change across Karo o a n ← Andean Tetrapoda successive generations in the heritable -50 0 — e Arthropods Molluscs r ←Cambrian explosion characteristics of biological populations. o ← Cryoge nian Ediacara biota – z ← Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity o Earliest animals ←Earliest plants at every level of biological organization, i Multicellular -1000 — c from kingdoms to species, and individual life ←Sexual reproduction organisms and molecules, such as DNA and – P proteins. The similarities between all present r -1500 — o day organisms indicate the presence of a t – e common ancestor from which all known r Eukaryotes o species, living and extinct, have diverged -2000 — z o through the process of evolution. More than i Huron ian – c 99 percent of all species, amounting to over ←Oxygen crisis [1] five billion species, that ever lived on -2500 — ←Atmospheric oxygen Earth are estimated to be extinct.[2][3] Estimates on the number of Earth's current – Photosynthesis Pong ola species range from 10 million to 14 -3000 — A million,[4] of which about 1.2 million have r c been documented and over 86 percent have – h [5] e not yet been described. However, a May a -3500 — n ←Earliest oxygen 2016 -

Phylogenetic Classification of Life

Proc. Natl. Accad. Sci. USA Vol. 93, pp. 1071-1076, February 1996 Evolution Archaeal- eubacterial mergers in the origin of Eukarya: Phylogenetic classification of life (centriole-kinetosome DNA/Protoctista/kingdom classification/symbiogenesis/archaeprotist) LYNN MARGULIS Department of Biology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003-5810 Conitribluted by Lynnl Marglulis, September 15, 1995 ABSTRACT A symbiosis-based phylogeny leads to a con- these features evolved in their ancestors by inferable steps (4, sistent, useful classification system for all life. "Kingdoms" 20). rRNA gene sequences (Trichomonas, Coronympha, Giar- and "Domains" are replaced by biological names for the most dia; ref. 11) confirm these as descendants of anaerobic eu- inclusive taxa: Prokarya (bacteria) and Eukarya (symbiosis- karyotes that evolved prior to the "crown group" (12)-e.g., derived nucleated organisms). The earliest Eukarya, anaero- animals, fungi, or plants. bic mastigotes, hypothetically originated from permanent If eukaryotes began as motility symbioses between Ar- whole-cell fusion between members of Archaea (e.g., Thermo- chaea-e.g., Thermoplasma acidophilum-like and Eubacteria plasma-like organisms) and of Eubacteria (e.g., Spirochaeta- (Spirochaeta-, Spirosymplokos-, or Diplocalyx-like microbes; like organisms). Molecular biology, life-history, and fossil ref. 4) where cell-genetic integration led to the nucleus- record evidence support the reunification of bacteria as cytoskeletal system that defines eukaryotes (21)-then an Prokarya while -

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

Lessons from 20 Years of Plant Genome Sequencing: an Unprecedented Resource in Need of More Diverse Representation

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.31.446451; this version posted May 31, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Lessons from 20 years of plant genome sequencing: an unprecedented resource in need of more diverse representation Authors: Rose A. Marks1,2,3, Scott Hotaling4, Paul B. Frandsen5,6, and Robert VanBuren1,2 1. Department of Horticulture, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA 2. Plant Resilience Institute, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA 3. Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa 4. School of Biological Sciences, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA 5. Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA 6. Data Science Lab, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA Keywords: plants, embryophytes, genomics, colonialism, broadening participation Correspondence: Rose A. Marks, Department of Horticulture, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA; Email: [email protected]; Phone: (603) 852-3190; ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7102-5959 Abstract The field of plant genomics has grown rapidly in the past 20 years, leading to dramatic increases in both the quantity and quality of publicly available genomic resources. With an ever- expanding wealth of genomic data from an increasingly diverse set of taxa, unprecedented potential exists to better understand the evolution and genome biology of plants. -

Local Drift Load and the Heterosis of Interconnected Populations

Heredity 84 (2000) 452±457 Received 5 November 1999, accepted 9 December 1999 Local drift load and the heterosis of interconnected populations MICHAEL C. WHITLOCK*, PAÈ R K. INGVARSSON & TODD HATFIELD Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z4 We use Wright's distribution of equilibrium allele frequency to demonstrate that hybrids between populations interconnected by low to moderate levels of migration can have large positive heterosis, especially if the populations are small in size. Bene®cial alleles neither ®x in all populations nor equilibrate at the same frequency. Instead, populations reach a mutation±selection±drift±migration balance with sucient among-population variance that some partially recessive, deleterious mutations can be masked upon crossbreeding. This heterosis is greatest with intermediate mutation rates, intermediate selection coecients, low migration rates and recessive alleles. Hybrid vigour should not be taken as evidence for the complete isolation of populations. Moreover, we show that heterosis in crosses between populations has a dierent genetic basis than inbreeding depression within populations and is much more likely to result from alleles of intermediate eect. Keywords: deleterious mutations, heterosis, hybrid ®tness, inbreeding depression, migration, population structure. Introduction genetic drift, producing ospring with higher ®tness than the parents (see recent reviews on inbreeding in Crow (1948) listed several reasons why crosses between Thornhill, 1993). Decades of work in agricultural individuals from dierent lines or populations might genetics con®rms this pattern: when divergent lines are have increased ®tness relative to more `pure-bred' crossed their F1 ospring often perform substantially 1individuals, so-called `hybrid vigour'. Crow commented better than the average of the parents (Falconer, 1981; on many possible mechanisms behind hybrid vigour, Mather & Jinks, 1982). -

Kingdom Animalia: Phylum Summary Table

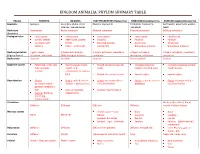

KINGDOM ANIMALIA: PHYLUM SUMMARY TABLE Phylum PORIFERA CNIDARIA PLATYHELMINTHES (flatworms) NEMATODA (roundworms) ANNELIDA (segmented worms) Examples Sponges Sea jellies, Hydra, coral Planaria, tapeworm Trichinella, hookworm, Earthworm, polychaete worms, colonies, sea anemones nematode leech Body type Asymmetry Radial symmetry Bilateral symmetry Bilateral symmetry Bilateral symmetry (Symmetry) Ecological roles Food source Food source Food source Food source Food source home / shelter Reef- home, protect Parasitic Parasitic Parasitic symbiotic with shores Eat dead animals – Aerate soil Aerate soil bacteria Chem. – anticancer saprophyte Breakdown material Breakdown material Body organization 2 germ layers 2 layers: ecto & endo 3 layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, 3 layers: ectoderm, 3 layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, (# germ layers) Ectoderm, endoderm With mesoglea between endoderm mesoderm, endoderm endoderm Body cavity Acoelom Acoelom Acoelom Pseudocoelom Coelom Digestive system Filter feed: collar cells, Gastrovascular cavity, Mouth and gastrovascular Complete digestive Complete digestive system: food vacuoles, mouth, and cavity system: mouth & anus mouth & anus osculum nematocysts to capture food Mouth also serves as anus Special organs Special organs Reproduction Sexual: Sexual: male & female Sexual: hermaphroditic – Sexual: separate sexes = Sexual: hermaphroditic – heramaphroditic – medusa – gametes fuse cross fertilization dioecious cross fertilization gametes released in H2O Asexual: budding, Asexual: fragmentation Asexual: budding, regeneration -

Construct a Plant Evolution Timeline

Constructing a Timeline of Plant Evolution Use this photo as a guide to creating an interactive timeline. Refer to Geologic Time Scale charts. A good resource is http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/help/timeform.php Use the “Plant Timeline Cards” found at the end of this document. Attach pictures with Velcro to allow for manipulation by students, and to “build” the timeline in increments. Teachers will need to find and print photos for “seed ferns” or omit that step in the timeline. Cut and paste the text below under each picture. Cyanobacteria: Also known as blue- Mosses: These have the first identifiable green algae, these are bacteria transport systems for water (xylem), and (prokaryotes – no nucleus) that can reproduce via spores, which encase sex photosynthesize. cells to prevent desiccation. They still need to live near water. First eukaryotes (cell nucleus): Scientist think that eukaryotes evolved via Hornworts: These developed the cuticle symbiosis, with one bacteria engulfing (waxy coating to prevent water loss) and another, but not digesting it. stomata (openings in the cuticle to allow Chloroplasts were originally for gas exchange.) All land plants except cyanobacteria engulfed by another liverworts have these two features. bacterium. Development of a true vascular system Anabaena: These water organisms allowed for better transport of water evolved from being unicellular to more and provided structural support for the complex, multicellular organisms. Their plant to grow taller. specialized cells help with nitrogen fixation. Club mosses: These were the first plants to have true leaves with veins. They also Stoneworts: Scientists think that developed roots as an anchoring system colonization of land occurred only once, to allow plant to grow taller.