Timeline of the Evolutionary History of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vertebrate Outline 2014

Winter 2014 EVOLUTION OF VERTEBRATES – LECTURE OUTLINE January 6 Introduction January 8 Unit 1 Vertebrate diversity and classification January 13 Unit 2 Chordate/Vertebrate bauplan January 15 Unit 3 Early vertebrates and agnathans January 20 Unit 4 Gnathostome bauplan; Life in water January 22 Unit 5 Early gnathostomes January 27 Unit 6 Chondrichthyans January 29 Unit 7 Major radiation of fishes: Osteichthyans February 3 Unit 8 Tetrapod origins and the invasion of land February 5 Unit 9 Extant amphibians: Lissamphibians February 10 Unit 10 Evolution of amniotes; Anapsids February 12 Midterm test (Units 1-8) February 17/19 Study week February 24 Unit 11 Lepidosaurs February 26 Unit 12 Mesozoic archosaurs March 3 March 5 Unit 13 Evolution of birds March 10 Unit 14 Avian flight March 12 Unit 15 Avian ecology and behaviour March 17 March 19 Unit 16 Rise of mammals March 24 Unit 17 Monotremes and marsupials March 26 Unit 18 Eutherians March 31 End of term test (Units 9-18) April 2 No lecture Winter 2014 EVOLUTION OF VERTEBRATES – LAB OUTLINE January 8 No lab January 15 Lab 1 Integuments and skeletons January 22 No lab January 29 Lab 2 Aquatic locomotion February 5 No lab February 12 Lab 3 Feeding: Form and function February 19 Study week February 26 Lab 4 Terrestrial locomotion March 5 No lab March 12 Lab 5 Flight March 19 No lab March 26 Lab 6 Sensory systems April 2 Lab exam Winter 2014 GENERAL INFORMATION AND MARKING SCHEME Professor: Dr. Janice M. Hughes Office: CB 4052; Telephone: 343-8280 Email: [email protected] Technologist: Don Barnes Office: CB 3015A; Telephone: 343-8490 Email: don [email protected] Suggested textbook: Pough, F.H., C, M, Janis, and J. -

Molecular and Functional Evolution of Hemoglobin in Perissodactyl

Molecular and functional evolution of hemoglobin in perissodactyl mammals (equids, tapirs, and rhinos) by Margaret Clapin A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Biological Sciences University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Canada © 2019 Abstract: In this thesis, the oxygen binding characteristics of recombinant hemoglobin (Hb) isoforms (HbA [α2β2] and HbA2 [α2δ2]) from the extinct woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) are compared with Sumatran rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) and black rhino (Diceros bicornis) Hb. The major Hb component (HbA) of horses (Equus caballus) was also examined, as its blood O2 affinity has a low thermal sensitivity. This trait is commonly associated with cold-adaptation as it permits O2 to be offloaded at the cool peripheral tissues of regionally endothermic mammals, though the mechanism(s) by which the oxygenation enthalpy is reduced in horse Hb is unknown. It was hypothesized that the woolly rhino Hb isoforms would have similarly low thermal sensitivities to that of horses, either through enhanced effector binding or by altering the energetic transition from the tense to the relaxed state of hemoglobin. To test this hypothesis the hemoglobin coding sequences for each of the above species were determined and their Hb isoforms expressed using E. coli and purified. Oxygen equilibrium curves were then determined in the presence and absence of allosteric effectors at 25 and 37°C. Horse HbA had a low sensitivity to 2,3- diphosphoglycerate (DPG), though its low temperature sensitivity was primarily driven by increased DPG binding at the lower test temperature. -

Lecture 20 - the History of Life on Earth

Lecture 20 - The History of Life on Earth Lecture 20 The History of Life on Earth Astronomy 141 – Autumn 2012 This lecture reviews the history of life on Earth. Rapid diversification of anaerobic prokaryotes during the Proterozoic Eon Emergence of Photosynthesis and the rise of O2 in the Earth’s atmosphere. Rise of Eukaryotes and the Cambrian Explosion in biodiversity at the start of the Phanerozoic Eon Colonization of land first by plants, then by animals Emergence of primates, then hominids, then humans. A brief digression on notation: “ya” = “years ago” Introduce a simple compact notation for writing the length of time before the present day. For example: “3.5 Billion years ago” “454 Million years ago” Gya = “giga-years ago”, hence 3.5 Gya = 3.5 Billion years ago Mya = “mega-years ago”, hence 454 Mya = 454 Million years ago [Note: some sources use Ga and Ma] Astronomy 141 - Winter 2012 1 Lecture 20 - The History of Life on Earth The four Eons of geological time. Hadean: 4.5 – 3.8 Gya: Formation, oceans & atmosphere Archaean: 3.8 – 2.5 Gya: Stromatolites & fossil bacteria Proterozoic: 2.5 Gya – 454 Mya: Eukarya and Oxygen Phanerozoic: since 454 Mya: Rise of plant and animal life The Archaean Eon began with the end of heavy bombardment ~3.8 Gya. Conditions stabilized. Oceans, but no O2 in the atmosphere. Stromatolites appear in the geological record ~3.5 Gya and thrived for >1 Billion years Rise of anaerobic microbes in the deep ocean & shores using Chemosynthesis. Time of rapid diversification of life driven by Natural Selection. -

The World at the Time of Messel: Conference Volume

T. Lehmann & S.F.K. Schaal (eds) The World at the Time of Messel - Conference Volume Time at the The World The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 2011 Frankfurt am Main, 15th - 19th November 2011 ISBN 978-3-929907-86-5 Conference Volume SENCKENBERG Gesellschaft für Naturforschung THOMAS LEHMANN & STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL (eds) The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference Frankfurt am Main, 15th – 19th November 2011 Conference Volume Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung IMPRINT The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Conference Volume Publisher PROF. DR. DR. H.C. VOLKER MOSBRUGGER Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Editors DR. THOMAS LEHMANN & DR. STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected]; [email protected] Language editors JOSEPH E.B. HOGAN & DR. KRISTER T. SMITH Layout JULIANE EBERHARDT & ANIKA VOGEL Cover Illustration EVELINE JUNQUEIRA Print Rhein-Main-Geschäftsdrucke, Hofheim-Wallau, Germany Citation LEHMANN, T. & SCHAAL, S.F.K. (eds) (2011). The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates. 22nd International Senckenberg Conference. 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main. Conference Volume. Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, Frankfurt am Main. pp. 203. -

Chapter 22 Notes: Introduction to Evolution

NOTES: Ch 22 – Descent With Modification – A Darwinian View of Life Our planet is home to a huge variety of organisms! (Scientists estimate of organisms alive today!) Even more amazing is evidence of organisms that once lived on earth, but are now . Several hundred million species have come and gone during 4.5 billion years life is believed to have existed on earth So…where have they gone… why have they disappeared? EVOLUTION: the process by which have descended from . Central Idea: organisms alive today have been produced by a long process of . FITNESS: refers to traits and behaviors of organisms that enable them to survive and reproduce COMMON DESCENT: species ADAPTATION: any inherited characteristic that enhances an organism’s ability to ~based on variations that are HOW DO WE KNOW THAT EVOLUTION HAS OCCURRED (and is still happening!!!)??? Lines of evidence: 1) So many species! -at least (250,000 beetles!) 2) ADAPTATIONS ● Structural adaptations - - ● Physiological adaptations -change in - to certain toxins 3) Biogeography: - - and -Examples: 13 species of finches on the 13 Galapagos Islands -57 species of Kangaroos…all in Australia 4) Age of Earth: -Rates of motion of tectonic plates - 5) FOSSILS: -Evidence of (shells, casts, bones, teeth, imprints) -Show a -We see progressive changes based on the order they were buried in sedimentary rock: *Few many fossils / species * 6) Applied Genetics: “Artificial Selection” - (cattle, dogs, cats) -insecticide-resistant insects - 7) Homologies: resulting from common ancestry Anatomical Homologies: ● comparative anatomy reveals HOMOLOGOUS STRUCTURES ( , different functions) -EX: ! Vestigial Organs: -“Leftovers” from the evolutionary past -Structures that Embryological Homologies: ● similarities evident in Molecular/Biochemical Homologies: ● DNA is the “universal” genetic code or code of life ● Proteins ( ) Darwin & the Scientists of his time Introduction to Darwin… ● On November 24, 1859, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. -

Ancient Metaproteomics: a Novel Approach for Understanding Disease And

Ancient metaproteomics: a novel approach for understanding disease and diet in the archaeological record Jessica Hendy PhD University of York Archaeology August, 2015 ii Abstract Proteomics is increasingly being applied to archaeological samples following technological developments in mass spectrometry. This thesis explores how these developments may contribute to the characterisation of disease and diet in the archaeological record. This thesis has a three-fold aim; a) to evaluate the potential of shotgun proteomics as a method for characterising ancient disease, b) to develop the metaproteomic analysis of dental calculus as a tool for understanding both ancient oral health and patterns of individual food consumption and c) to apply these methodological developments to understanding individual lifeways of people enslaved during the 19th century transatlantic slave trade. This thesis demonstrates that ancient metaproteomics can be a powerful tool for identifying microorganisms in the archaeological record, characterising the functional profile of ancient proteomes and accessing individual patterns of food consumption with high taxonomic specificity. In particular, analysis of dental calculus may be an extremely valuable tool for understanding the aetiology of past oral diseases. Results of this study highlight the value of revisiting previous studies with more recent methodological approaches and demonstrate that biomolecular preservation can have a significant impact on the effectiveness of ancient proteins as an archaeological tool for this characterisation. Using the approaches developed in this study we have the opportunity to increase the visibility of past diseases and their aetiology, as well as develop a richer understanding of individual lifeways through the production of molecular life histories. iii iv List of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... -

Integrative and Comparative Biology Integrative and Comparative Biology, Volume 58, Number 4, Pp

Integrative and Comparative Biology Integrative and Comparative Biology, volume 58, number 4, pp. 605–622 doi:10.1093/icb/icy088 Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology SYMPOSIUM INTRODUCTION The Temporal and Environmental Context of Early Animal Evolution: Considering All the Ingredients of an “Explosion” Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/article-abstract/58/4/605/5056706 by Stanford Medical Center user on 15 October 2018 Erik A. Sperling1 and Richard G. Stockey Department of Geological Sciences, Stanford University, 450 Serra Mall, Building 320, Stanford, CA 94305, USA From the symposium “From Small and Squishy to Big and Armored: Genomic, Ecological and Paleontological Insights into the Early Evolution of Animals” presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology, January 3–7, 2018 at San Francisco, California. 1E-mail: [email protected] Synopsis Animals originated and evolved during a unique time in Earth history—the Neoproterozoic Era. This paper aims to discuss (1) when landmark events in early animal evolution occurred, and (2) the environmental context of these evolutionary milestones, and how such factors may have affected ecosystems and body plans. With respect to timing, molecular clock studies—utilizing a diversity of methodologies—agree that animal multicellularity had arisen by 800 million years ago (Ma) (Tonian period), the bilaterian body plan by 650 Ma (Cryogenian), and divergences between sister phyla occurred 560–540 Ma (late Ediacaran). Most purported Tonian and Cryogenian animal body fossils are unlikely to be correctly identified, but independent support for the presence of pre-Ediacaran animals is recorded by organic geochemical biomarkers produced by demosponges. -

Plant Evolution an Introduction to the History of Life

Plant Evolution An Introduction to the History of Life KARL J. NIKLAS The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction 1 1 Origins and Early Events 29 2 The Invasion of Land and Air 93 3 Population Genetics, Adaptation, and Evolution 153 4 Development and Evolution 217 5 Speciation and Microevolution 271 6 Macroevolution 325 7 The Evolution of Multicellularity 377 8 Biophysics and Evolution 431 9 Ecology and Evolution 483 Glossary 537 Index 547 v Introduction The unpredictable and the predetermined unfold together to make everything the way it is. It’s how nature creates itself, on every scale, the snowflake and the snowstorm. — TOM STOPPARD, Arcadia, Act 1, Scene 4 (1993) Much has been written about evolution from the perspective of the history and biology of animals, but significantly less has been writ- ten about the evolutionary biology of plants. Zoocentricism in the biological literature is understandable to some extent because we are after all animals and not plants and because our self- interest is not entirely egotistical, since no biologist can deny the fact that animals have played significant and important roles as the actors on the stage of evolution come and go. The nearly romantic fascination with di- nosaurs and what caused their extinction is understandable, even though we should be equally fascinated with the monarchs of the Carboniferous, the tree lycopods and calamites, and with what caused their extinction (fig. 0.1). Yet, it must be understood that plants are as fascinating as animals, and that they are just as important to the study of biology in general and to understanding evolutionary theory in particular. -

Studies of the Laboulbeniomycetes: Diversity, Evolution, and Patterns of Speciation

Studies of the Laboulbeniomycetes: Diversity, Evolution, and Patterns of Speciation The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40049989 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ! STUDIES OF THE LABOULBENIOMYCETES: DIVERSITY, EVOLUTION, AND PATTERNS OF SPECIATION A dissertation presented by DANNY HAELEWATERS to THE DEPARTMENT OF ORGANISMIC AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Biology HARVARD UNIVERSITY Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2018 ! ! © 2018 – Danny Haelewaters All rights reserved. ! ! Dissertation Advisor: Professor Donald H. Pfister Danny Haelewaters STUDIES OF THE LABOULBENIOMYCETES: DIVERSITY, EVOLUTION, AND PATTERNS OF SPECIATION ABSTRACT CHAPTER 1: Laboulbeniales is one of the most morphologically and ecologically distinct orders of Ascomycota. These microscopic fungi are characterized by an ectoparasitic lifestyle on arthropods, determinate growth, lack of asexual state, high species richness and intractability to culture. DNA extraction and PCR amplification have proven difficult for multiple reasons. DNA isolation techniques and commercially available kits are tested enabling efficient and rapid genetic analysis of Laboulbeniales fungi. Success rates for the different techniques on different taxa are presented and discussed in the light of difficulties with micromanipulation, preservation techniques and negative results. CHAPTER 2: The class Laboulbeniomycetes comprises biotrophic parasites associated with arthropods and fungi. -

A Critique of Phanerozoic Climatic Models Involving Changes in The

Earth-Science Reviews 56Ž. 2001 1–159 www.elsevier.comrlocaterearscirev A critique of Phanerozoic climatic models involving changes in the CO2 content of the atmosphere A.J. Boucot a,), Jane Gray b,1 a Department of Zoology, Oregon State UniÕersity, CorÕallis, OR 97331, USA b Department of Biology, UniÕersity of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403, USA Received 28 April 1998; accepted 19 April 2001 Abstract Critical consideration of varied Phanerozoic climatic models, and comparison of them against Phanerozoic global climatic gradients revealed by a compilation of Cambrian through Miocene climatically sensitive sedimentsŽ evaporites, coals, tillites, lateritic soils, bauxites, calcretes, etc.. suggests that the previously postulated climatic models do not satisfactorily account for the geological information. Nor do many climatic conclusions based on botanical data stand up very well when examined critically. Although this account does not deal directly with global biogeographic information, another powerful source of climatic information, we have tried to incorporate such data into our thinking wherever possible, particularly in the earlier Paleozoic. In view of the excellent correlation between CO2 present in Antarctic ice cores, going back some hundreds of thousands of years, and global climatic gradient, one wonders whether or not the commonly postulated Phanerozoic connection between atmospheric CO2 and global climatic gradient is more coincidence than cause and effect. Many models have been proposed that attempt to determine atmospheric composition and global temperature through geological time, particularly for the Phanerozoic or significant portions of it. Many models assume a positive correlation between atmospheric CO2 and surface temperature, thus viewing changes in atmospheric CO2 as playing the critical role in r regulating climate temperature, but none agree on the levels of atmospheric CO2 through time. -

Inferring Echolocation in Ancient Bats Arising From: N

NATURE | Vol 466 | 19 August 2010 BRIEF COMMUNICATIONS ARISING Inferring echolocation in ancient bats Arising from: N. Veselka et al. Nature 463, 939–942 (2010) Laryngeal echolocation, used by most living bats to form images of O. finneyi falls outside the size range seen in living echolocating bats their surroundings and to detect and capture flying prey1,2, is con- and is similar to the proportionally smaller cochleae of bats that lack sidered to be a key innovation for the evolutionary success of bats2,3, laryngeal echolocation4,8, suggesting that it did not echolocate. and palaeontologists have long sought osteological correlates of echolocation that can be used to infer the behaviour of fossil bats4–7. Veselka et al.8 argued that the most reliable trait indicating echoloca- tion capabilities in bats is an articulation between the stylohyal bone (part of the hyoid apparatus that supports the throat and larynx) and a the tympanic bone, which forms the floor of the middle ear. They examined the oldest and most primitive known bat, Onychonycteris finneyi (early Eocene, USA4), and argued that it showed evidence of this stylohyal–tympanic articulation, from which they concluded that O. finneyi may have been capable of echolocation. We disagree with their interpretation of key fossil data and instead argue that O. finneyi was probably not an echolocating bat. The holotype of O. finneyi shows the cranial end of the left stylohyal resting on the tympanic bone (Fig. 1c–e). However, the stylohyal on the right side is in a different position, the tip of the stylohyal extends beyond the tympanic on both sides of the skull, and both tympanics are crushed. -

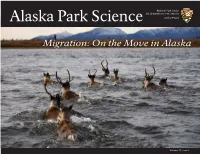

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest