Peasant Servitude in Mediaeval Catalonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Century Barcelona

Immigration and Integration in a Mediterranean City: The Making of the Citizen in Fifteenth- Century Barcelona Volume 1 Carolina Obradors Suazo Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, July 2015. European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Immigration and Integration in a Mediterranean City: The Making of the Citizen in Fifteenth-Century Barcelona. Volume 1 Carolina Obradors Suazo Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Luca Molà, (EUI, Supervisor). Prof. Regina Grafe, (EUI, Second Reader). Dr. Roser Salicrú i Lluch (Institució Milà i Fontanals -CSIC, External Supervisor). Prof. Bartolomé Yun-Casalilla (EUI, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Seville). Prof. James Amelang (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid). © Carolina Obradors Suazo, 2015. No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Immigration and Integration in a Mediterranean City: The Making of the Citizen in Fifteenth-Century Barcelona Carolina Obradors Suazo Thesis Supervisor: Professor Luca Molà Abstract. This thesis explores the norms, practices, and experiences that conditioned urban belonging in Late Medieval Barcelona. A combination of institutional, legal, intellectual and cultural analysis, the dissertation investigates how citizenship evolved and functioned on the Barcelonese stage. To this end, the thesis is structured into two parts. Part 1 includes four chapters, within which I establish the legal and institutional background of the Barcelonese citizen. Citizenship as a fiscal and individual privilege is contextualised within the negotiations that shaped the limits and prerogatives of monarchical and municipal power from the thirteenth to the late fourteenth centuries. -

Catalonia 1400 the International Gothic Style

Lluís Borrassà: the Vocation of Saint Peter, a panel from the Retable of Saint Peter in Terrassa Catalonia 1400 The International Gothic Style Organised by: Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya. From 29 March to 15 July 2012 (Temporary Exhibitions Room 1) Curator: Rafael Cornudella (head of the MNAC's Department of Gothic Art), with the collaboration of Guadaira Macías and Cèsar Favà Catalonia 1400. The International Gothic Style looks at one of the most creative cycles in the history of Catalan art, which coincided with the period in western art known as the 'International Gothic Style'. This period, which began at the end of the 14th century and went on until the mid-15th century, gave us artists who played a central role in the history of European art, as in the case of Lluís Borrassà, Rafael Destorrents, Pere Joan and Bernat Martorell. During the course of the 14th century a process of dialogue and synthesis took place between the two great poles of modernity in art: on one hand Paris, the north of France and the old Netherlands, and on the other central Italy, mainly Tuscany. Around 1400 this process crystallised in a new aesthetic code which, despite having been formulated first and foremost in a French and 'Franco- Flemish' ambit, was also fed by other international contributions and immediately spread across Europe. The artistic dynamism of the Franco- Flemish area, along with the policies of patronage and prestige of the French ruling House of Valois, explain the success of a cultural model that was to captivate many other European princes and lords. -

Ackelsberg L

• • I I Free Women of Spain Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women I Martha A. Ackelsberg l I f I I .. AK PRESS Oakland I West Virginia I Edinburgh • Ackelsberg. Martha A. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women Lihrary of Congress Control Numher 2003113040 ISBN 1-902593-96-0 Published hy AK Press. Reprinted hy Pcrmi"inn of the Indiana University Press Copyright 1991 and 2005 by Martha A. Ackelsherg All rights reserved Printed in Canada AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612-1163 USA (510) 208-1700 www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh. EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555-5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] The addresses above would be delighted to provide you with the latest complete AK catalog, featur ing several thousand books, pamphlets, zines, audio products, videos. and stylish apparel published and distributed bv AK Press. A1tern�tiv�l�! Uil;:1t r\llr "-""'l:-,:,i!'?� f2":' �!:::: :::::;:;.p!.::.;: ..::.:.:..-..!vo' :uh.. ,.",i. IIt;W� and updates, events and secure ordering. Cover design and layout by Nicole Pajor A las compafieras de M ujeres Libres, en solidaridad La lucha continua Puiio ell alto mujeres de Iberia Fists upraised, women of Iheria hacia horiz,ontes prePiados de luz toward horizons pregnant with light por rutas ardientes, on paths afire los pies en fa tierra feet on the ground La frente en La azul. face to the blue sky Atirmondo promesas de vida Affimling the promise of life desafiamos La tradicion we defy tradition modelemos la arcilla caliente we moLd the warm clay de un mundo que nace del doLor. -

Coalition Politics in Catalan Local Governments, 1979-2011

Coalition Politics in Catalan Local Governments, 1979-2011 Santi Martínez Farrero ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) i a través del Dipòsit Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX ni al Dipòsit Digital de la UB. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX o al Dipòsit Digital de la UB (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) y a través del Repositorio Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR o al Repositorio Digital de la UB. -

(At the Service of the Roman Empire) and the Subsequent Economic Imperialism

Image: Map of Western Europe, by Fernão Vaz Dourado (1520-1580). Estimated actual date: ≈1705. European colonization (at the service of the Roman Empire) and the subsequent Economic Imperialism Author: Andreu Marfull-Pujadas 2017 © All rights reserved Exercise done for the Project of the Scientific Direction "New Chronology" - НЕВ ХРОНОЛОГИЈАА - directed by the professors A.T.Fomenko and G.V.Nosovskiy Work developed in the GLOBAL DIAGRAM OF THE DOUBLE CHRONOLOGICAL MANIPULATION OF THE HUMAN HISTORY - Representation of the Global Chronological Map of the "New Chronology" (Part 3) V.3.0 2017/10/12 Posted on 2018/01/12 Index 1. THE RECONSTRUCTION OF DILATED HISTORY ................................................... 3 1.1. The Empire of Human Civilizations, 10th-21st centuries ......................................................................... 3 1.2. Egypt = Rome = Greece, the Original Empire .......................................................................................... 4 1.3. Archaeology and “ancient” Thought ......................................................................................................... 5 1.4. Jerusalem = Holy Land = Several cities ................................................................................................... 5 1.5. America before to “1492” .......................................................................................................................... 7 1.6. The transformation of the Horde-Ottoman Alliance into the Janua (Genoa)-Palaiologos Alliance .......... 8 -

The University and the Region: an Historical Overview and Some Reflections on the Case of Catalonia

CONEIXEMENT I SOCIETAT 04 ARTICLES THE UNIVERSITY AND THE REGION: AN HISTORICAL OVERVIEW AND SOME REFLECTIONS ON THE CASE OF CATALONIA Ricard Pié* The increase in the number of publicly funded universities in Catalonia, the emergence of four private universi- ties, the major urban impact on the cities of Girona, Lleida, Reus, Tarragona and Vic as a result of the implantation of their respective universities, together with demographic factors such as the decline in the higher education population, as well as the need to rationalise the present map of universities in Catalonia, call for a considered appraisal of the relationship between the university and the region, as well as the relevance of that relationship to regional and academic restructuring policies affecting Catalan universities in the future. Contents 1. The university and its surrounding region 2. The founding of the medieval university, an urban phenomenon 3. The crisis of the traditional university model and the re-founding of the university as a temple of knowledge 4. The American experience: from rural college to mass university 5. The university as a motor of regional development 6. Spanish universities and their struggle for renewal 7. The difficult years, from the Spanish Civil War to the coming of democracy 8. The explosion of the university map in Spain under the new autonomous regions 9. The genesis of today’s university map in Catalonia 10. Some questions concerning the Catalan university map in relation to the differential value of region * Ricard PIÉ is an architect and senior lecturer at the Polytechnic University of Catalonia 16 THE UNIVERSITY AND THE REGION: AN HISTÒRICAL OVERVIEW AND SOME REFLECTIONS ON THE CASE OF CATALONIA 1. -

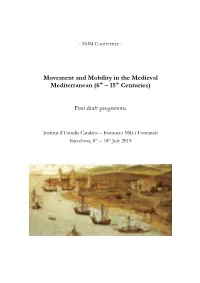

First Draft Programme

- SMM Conference - Movement and Mobility in the Medieval Mediterranean (6th – 15th Centuries) First draft programme Institut d’Estudis Catalans – Institució Milà i Fontanals Barcelona, 8th – 10th July 2019 Monday 8th Tuesday 9th Wednesday 10th Thursday 11th Friday 12th 9h30 S2 - panels 9h30 S6 - panels 9h30 S9 - panels 11h00 6-7-8-9-10 11h00 26-27-28-29-30 11h00 41-42-43-44-45 11h00 11h00 11h00 Coffee break Coffee break Coffee break 11h30 11h30 11h30 11h30 S3 - panels 11h30 S7 - panels 11h30 Simon Barton’s 13h00 11-12-13-14-15 13h00 31-32-33-34-35 13h00 Homage Programme summary 14h00 13h00 13h00 Opening session Lunchtime Lunchtime 14h30 14h30 14h30 Full day excursion to medieval 14h30 SMM’s Book and Girona, Sant Pere 14h45 Journal Prizes 14h30 S4 - panels 14h30 Keynote: Amy G. de Rodes medieval 16h00 16-17-18-19-20 16h00 Remensnyder monastery, fishing 14h45 and touristic Break 15h00 village of el Port de la Selva (from 9 15h00 Keynote: Petra 16h00 16h00 am to 9 pm) Coffee break Coffee break 16h30 M. Sijpesteijn 16h30 16h30 16h30 16h30 S5 (panels 16h30 S8 - panels Coffee break 17h00 18h00 21-22-23-24-25) 18h00 36-37-38-39-40 17h00 S1 - panels 18h00 AGM Visit to ‘Medieval 18h30 1-2-3-4-5 20h00 Barcelona’ and 19h00 18h30 Conference ‘700 years of the Reception 20h 20h00 dinner ACA’ exhibitions Monday 8th of July 14h00 – 14h30 Opening Session 14h30 – 14h45 SMM’s Book and Journal Prizes 14h45 – 15h00 Break 15h00 – 16h30 Keynote Petra M. Sijpesteijn (Leiden University): Global Networks: Mobility and Exchange in the Mediterranean (600-1000) The establishment of the Muslim Empire in the mid-seventh century C.E. -

Law, Liturgy, and Sacred Space in Medieval Catalonia and Southern France, 800-1100

Law, Liturgy, and Sacred Space in Medieval Catalonia and Southern France, 800-1100 Adam Christopher Matthews Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 1 ©2021 Adam Christopher Matthews All Rights Reserved 2 Abstract Law, Liturgy, and Sacred Space in Medieval Catalonia and Southern France, 800-1100 Adam Christopher Matthews With the collapse of the Visigothic kingdom, the judges of Catalonia and southern France worked to keep the region‘s traditional judicial system operable. Drawing on records of judicial proceedings and church dedications from the ninth century to the end of the eleventh, this dissertation explores how judges devised a liturgically-influenced court strategy to invigorate rulings. They transformed churches into courtrooms. In these spaces, changed by merit of the consecration rite, community awe for the power infused within sacred space could be utilized to achieve consensus around the legitimacy of dispute outcomes. At the height of a tribunal, judges brought litigants and witnesses to altars, believed to be thresholds of Heaven, and compelled them to authenticate their testimony before God and his saints. Thus, officials supplemented human means of enforcement with the supernatural powers permeating sanctuaries. This strategy constitutes a hybridization of codified law and the belief in churches as real sacred spaces, a conception that emerged from the Carolingian liturgical reforms of the ninth century. In practice, it provided courts with a means to enact the mandates from the Visigothic Code and to foster stability. The result was a flexible synthesis of law, liturgy, and sacred space that was in many cases capable of harnessing spiritual and community pressure in legal proceedings. -

Memory in the Middle Ages: Approaches from Southwestern

CMS MEMORY IN THE MIDDLE AGES APPROACHES FROM SOUTHWESTERN EUROPE Memory was vital to the functioning of the medieval world. People in medieval societies shared an identity based on commonly held memo- MEMORY IN THE MIDDLE AGES THE MIDDLE IN MEMORY ries. Religions, rulers, and even cities and nations justifi ed their exis- tence and their status through stories that guaranteed their deep and unbroken historical roots. The studies in this interdisciplinary collec- tion explore how manifestations of memory can be used by historians as a prism through which to illuminate European medieval thought and value systems.The contributors have drawn a link between memory and medieval science, management of power and remembrance of the dead ancestors through examples from southern Europe as a means and Studies CARMEN Monographs of enriching and complicating our study of the Middle Ages; this is a region with a large amount of documentation but which to date has not been widely studied. Finally, the contributors have researched the role of memory as a means to sustain identity and ideology from the past to the present. This book has two companion volumes, dealing with ideology and identity as part of a larger project that seeks to map and interrogate the signifi cance of all three concepts in the Middle Ages in the West. CARMEN Monographs and Studies seeks to explore the movements of people, ideas, religions and objects in the medieval period. It welcomes publications that deal with the migration of people and artefacts in the Middle Ages, the adoption of Christianity in northern, Baltic, and east- MEMORY IN central Europe, and early Islam and its expansion through the Umayyad caliphate. -

Social Structure of Catalonia

THE SOCIAL STRUCTURE OF CATALONIA By SALVADOR GINER 1984 THE ANGLO-CATALAN SOCIETY THE ANGLO-CATALAN SOCIETY OCCASIONAL PUBLICATIONS No 1. Salvador Giner. The Social Structure of Catalonia. No 2. J Salvat-Papasseit. Selected Poems. Translated with an Introduction by D. Keown and T. Owen. © Salvador Giner, 1980. Printed by The University of Sheffield Printing Unit. Cover design by Joan Gili. ISSN No. 0144-5863 ISBN No. 09507137 08 IN MEMORIAM JOSEP MARIA BATISTA I ROCA (1895-1978) Dr. J. M. Batista i Roca, founder member of the Anglo-Catalan Society and its first Honorary Life President, always hoped that the Society would at some stage be able to publish some of the work of its members and guest speakers. Unfortunately this was never possible during his lifetime, but now that the Society, with the help of a grant from Omnium Cultural, is undertaking the publication of Occasional Papers it seems appropriate that this Series as a whole should be dedicated to the fond memory which the Society holds of him. CONTENTS Foreword 1 I. The historical roots of an open society. 4 II. Social classes and the rise of Catalan industrial capitalism. 15 III. A broken progress. 28 IV. The structure and change of Catalan society, 1939-1980. 38 V. The reconquest of democracy. 54 VI. The future of the Catalans. 65 Appendices. Maps. 75 A Select Bibliography. 77 FOREWORD A la memòria de Josep Maria Sariola i Bosch, català com cal The following essay is based on a lecture given at a meeting of the Anglo- Catalan Society in November 1979* Members of the Society's Committee kindly suggested that I write up the ideas presented at that meeting so that they could be published under its auspices in a series of Occasional Papers then being planned. -

The Pyrenees Region by Friedrich Edelmayer

The Pyrenees Region by Friedrich Edelmayer The Pyrenees region encompasses areas from the Kingdom of Spain, the Republic of France and the Principality of An- dorra. It is also linguistically heterogeneous. In addition to the official state languages Spanish and French, Basque, Aragonese, Catalan and Occitan are spoken. All of these languages have co-official character in certain regions of Spain, although not in France. In the modern era, changes to the political-geographical boundary between the present states of France and Spain occurred in the 16th century, when the Kingdom of Navarre was divided into two unequal parts, and in 1659/1660 when northern Catalonia became part of France after the Treaty of the Pyrenees. However, the border area between France and Spain was not only a stage for conflict, but also a setting for numerous communi- cation and transfer processes. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Languages and Peoples in the Pyrenees 1. Basque 2. Aragonese 3. Catalan 4. Occitan 5. Spanish and French 3. The History of the Pyrenees Region 4. Transfer and Communication Processes in the Pyrenees 5. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Bibliography 3. Notes Indices Citation Introduction There are three states today in the area of Europe which is dominated by the Pyrenees Mountains: the French Repub- lic (République française), the Kingdom of Spain (Reino de España) and, in the middle of the (high) mountains, the small Principality of Andorra (Principat d'Andorra). The border between France and Spain runs today mostly along the main ridge of the mountains and, with few exceptions, along the watershed between the rivers that meet the sea at the Spanish coast and those that meet the sea at the French coast. -

Stranding of Freshwater Turtles at Different Sea Beaches in Catalonia

Bol. Asoc. Herpetol. Esp. (2020) 31(1) Preprint-175 Stranding of freshwater turtles at different sea beaches in Catalonia after storm Gloria Ramón Mascort1,2, Enric Badosa3, Joan Budó2, Xavier Capalleras2, Joaquim Soler4 & Albert Martínez-Silvestre4 1 Cl. La Jonquera, 17. 2. 17600 Figueres. Girona. Spain. C.e.: [email protected] 2 Centre de reproducció de tortugues (CRT) de l’Albera. 17780 Garriguella. Girona. Spain. 3 Cl. Pau Costa, 7. 08350 Arenys de Mar. Barcelona. Spain. 4 CRARC. Av. Maresme, 45. 08783 Masquefa. Barcelona. Spain. Fecha de aceptación: 17 de junio de 2020. Key words: Flash flood, Mauremys leprosa, Trachemys scripta, Emys orbicularis, Invasive species. RESUMEN: La tormenta Gloria afectó intensamente el litoral mediterráneo de la península ibé- rica del 19 al 26 de enero de 2020, con un importante temporal marítimo y muy abundantes lluvias que en algunos puntos rozaron los 500 mm. El caudal de los principales ríos de Cataluña aumentó extraordinariamente y arrastró centenares de tortugas acuáticas hacia el mar, mientras que el temporal marítimo diseminó los animales por las playas próximas a esos ríos. En días posteriores se encontraron más de 200 tortugas de cinco especies a lo largo de la costa y en algu- nos casos alejadas algunas decenas de kilómetros de la desembocadura del río correspondiente. En el presente estudio se constata la capacidad de supervivencia y la potencial capacidad colo- nizadora del galápago leproso, ya sea a través de una misma cuenca fluvial o transportados por las olas de un temporal. También se destaca la necesidad de proteger adecuadamente el hábitat de las especies de tortugas autóctonas y limitar la expansión de las especies exóticas e invasoras.