EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Transferring Water from the Rhone to Barcelona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Foix Routes Marked with an Asterisk (*)

a Barcelona Standard symbols Facilities and services Vilafranca BV del Penedès motorway park ofce -2128 TGV dual carriageway information Signposted itineraries road construction of interest trail museum, permanent N-340a exhibition These are circular routes that return to the starting point, except GR (long-distance footpath) cultural facility N-340 El Foix routes marked with an asterisk (*). The routes are designed to audiovisuals B-212 PR (short-distance park footpath) documentation centre reveal the richness of the natural and cultural heritage of different Cal Rubió SL (local footpath) places within the park and are usually adapted for families. nature school PR-C 148 IP park itinerary bird observatory AP-7 Train / TGV start of signposted itinerary el Sant Sepulcre A B A B urban area la Múnia 1 2 hrs 7.8 km 3 30 min 1.4 km rock shelter/cave (Castellví de la Marca) els Monjos park boundary spring (Santa Margarida i els Monjos) From castle to castle: from Penyafort Along the riverbank from El Foix to PR-C 148 boundary of other food produce Moja to Castellet* Penyafort protected spaces winery C-15 Starting point: Penyafort castle (Santa Starting point: Penyafort castle (Santa peak la Costa restaurant Margarida i Els Monjos) Margarida i Els Monjos) Catalan farmhouse, GR 92-3 Molí del Foix Torre building rural tourism nt d e M el Serral a closed-off pat recreational area ta -r font de Mata-rectors e 2 1 hr A B 4 km c signposted controlled shing BV 181,8 m Espitlles to Sant Miquel d’Olèrdola itineraries -2176 rs railway station Els Monjos -

As Indicators of Habitat Quality in Mediterranean Streams and Rivers in the Province of Barcelona (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula)

International Journal of Odonatology, 2016 Vol. 19, No. 3, 107–124, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13887890.2016.1172991 Dragonflies (Insecta: Odonata) as indicators of habitat quality in Mediterranean streams and rivers in the province of Barcelona (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula) Ricard Martín∗ and Xavier Maynou Catalan Odonata Study Group, Institució Catalana d’Història Natural, Barcelona, Spain (Received 7 November 2015; final version received 24 March 2016) In a field study carried out in 2011 and 2014 adult dragonflies were identified as a rapid and easy-to-use means of assessing habitat quality and biological integrity of Mediterranean streams and rivers in the province of Barcelona (Region Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula). The study included sampling sites from five different river catchments: Besòs, Foix, Llobregat, Ter and Tordera. Multivariate statistical procedures and indicator species analysis were used to investigate the relationship between river ecological status, study sites and dragonfly species or species assemblages’ occurrence. The dragonfly association identified with western Mediterranean permanent streams, i.e. Cordulegaster boltonii, Boyeria irene, Onychogom- phus uncatus and Calopteryx virgo meridionalis, was found only at the sites with the highest status. All these taxa were identified as indicator species of sites with the best scores for the macroinvertebrate based IBMWP index and for the combined IASPT index, which reflects the sensitivity of the macroinvertebrate families present to environmental changes; besides, B. irene and C. virgo meridionalis alsoprovedtobe indicator species of the riparian forest quality index and C. boltonii of the more inclusive ECOSTRIMED, which assesses the overall conservation status of the riverine habitats. The information obtained on habi- tat preferences and indicator value showed that adults of these taxa may constitute a valuable tool for preliminary or complementary cost-effective monitoring of river status and restoration practices as part of a broader set of indices reflecting biodiversity and ecosystem integrity. -

Century Barcelona

Immigration and Integration in a Mediterranean City: The Making of the Citizen in Fifteenth- Century Barcelona Volume 1 Carolina Obradors Suazo Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, July 2015. European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Immigration and Integration in a Mediterranean City: The Making of the Citizen in Fifteenth-Century Barcelona. Volume 1 Carolina Obradors Suazo Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Luca Molà, (EUI, Supervisor). Prof. Regina Grafe, (EUI, Second Reader). Dr. Roser Salicrú i Lluch (Institució Milà i Fontanals -CSIC, External Supervisor). Prof. Bartolomé Yun-Casalilla (EUI, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Seville). Prof. James Amelang (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid). © Carolina Obradors Suazo, 2015. No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Immigration and Integration in a Mediterranean City: The Making of the Citizen in Fifteenth-Century Barcelona Carolina Obradors Suazo Thesis Supervisor: Professor Luca Molà Abstract. This thesis explores the norms, practices, and experiences that conditioned urban belonging in Late Medieval Barcelona. A combination of institutional, legal, intellectual and cultural analysis, the dissertation investigates how citizenship evolved and functioned on the Barcelonese stage. To this end, the thesis is structured into two parts. Part 1 includes four chapters, within which I establish the legal and institutional background of the Barcelonese citizen. Citizenship as a fiscal and individual privilege is contextualised within the negotiations that shaped the limits and prerogatives of monarchical and municipal power from the thirteenth to the late fourteenth centuries. -

Catalan Farmhouses and Farming Families in Catalonia Between the 16Th and Early 20Th Centuries

CATALAN HISTORICAL REVIEW, 9: 71-84 (2016) Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Barcelona DOI: 10.2436/20.1000.01.122 · ISSN: 2013-407X http://revistes.iec.cat/chr/ Catalan farmhouses and farming families in Catalonia between the 16th and early 20th centuries Assumpta Serra* Institució Catalana d’Estudis Agraris Received 20 May 2015 · Accepted 15 July 2015 Abstract The masia (translated here as the Catalan farmhouse), or the building where people reside on a farming estate, is the outcome of the landscape where it is located. It underwent major changes from its origins in the 11th century until the 16th century, when its evolu- tion peaked and a prototype was reached for Catalonia as a whole. For this reason, in the subsequent centuries the model did not change, but building elements were added to it in order to adapt the home to the times. Catalan farmhouses are a historical testimony, and their changes and enlargements always reflect the needs of their inhabitants and the technological possibilities of the period. Keywords: evolution, architectural models, farmhouses, rural economy, farming families Introduction techniques or the spread of these techniques became availa- ble to more and more people. Larger or more numerous Some years ago, historians stopped studying only the ma- rooms characterised the evolution of a structure that was jor political events or personalities to instead focus on as- originally called a hospici, domus, casa or alberg, although pects that were closer to the majority of the people, because we are not certain of the reason behind such a variety of this is where the interest lies: in learning about our ances- words. -

Fuerzas Hidroeléctricas Del Segre, the Gomis Family, Which Founded and Owned the Company, Had Been Involved in the Electricity Business for a Long Time

SHORT ARTICLEST he Image Lourdes Martínez Collection: Fuerzas Prado PHOTOGRAPHY Hidroeléctricas Spain del Segre The cataloguing and simultaneous digitisation should be made of the pictures of workers at of images generated by the Fuerzas Hidro- great heights on the dam wall, transmission eléctricas del Segre company is a project car- towers or bridges), to the difficulties posed by ried out in the National Archive of Catalonia the weather. In this regard, the collection in collaboration with the Fundación Endesa, includes some photographs of the minor resulting in the collection becoming easy to flooding events of the river in March 1947, consult not only in the actual Archive, but also December 1949, May 1950, and May 1956 through the Internet. This was a long-che- (two or three photos per weather phenome- rished ambition of the ANC, since the Fuerzas non), and also of the winds in the winter of Hidroeléctricas del Segre is one of the most 1949-1950. The great flood of June 1953 of comprehensive collections in terms of being the river Segre is particularly well documented, able to monitor the construction of a hydro- with 63 photographs, which convincingly con- electric complex. I am referring, more spe- vey how the river severely punished the area in cifically, to the hydroelectric station of Oliana1 . general and more particularly building work on Indeed, of the 2,723 units catalogued in the the dam. collection, approximately 1,500 pertain to the aforementioned project. These pictures also allow us to study the engi- neering techniques and tools used in the 1940s The construction of the Oliana dam was un- and 1950s, particularly the machinery used, dertaken in 1946. -

Catalonia 1400 the International Gothic Style

Lluís Borrassà: the Vocation of Saint Peter, a panel from the Retable of Saint Peter in Terrassa Catalonia 1400 The International Gothic Style Organised by: Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya. From 29 March to 15 July 2012 (Temporary Exhibitions Room 1) Curator: Rafael Cornudella (head of the MNAC's Department of Gothic Art), with the collaboration of Guadaira Macías and Cèsar Favà Catalonia 1400. The International Gothic Style looks at one of the most creative cycles in the history of Catalan art, which coincided with the period in western art known as the 'International Gothic Style'. This period, which began at the end of the 14th century and went on until the mid-15th century, gave us artists who played a central role in the history of European art, as in the case of Lluís Borrassà, Rafael Destorrents, Pere Joan and Bernat Martorell. During the course of the 14th century a process of dialogue and synthesis took place between the two great poles of modernity in art: on one hand Paris, the north of France and the old Netherlands, and on the other central Italy, mainly Tuscany. Around 1400 this process crystallised in a new aesthetic code which, despite having been formulated first and foremost in a French and 'Franco- Flemish' ambit, was also fed by other international contributions and immediately spread across Europe. The artistic dynamism of the Franco- Flemish area, along with the policies of patronage and prestige of the French ruling House of Valois, explain the success of a cultural model that was to captivate many other European princes and lords. -

Impacts of Use and Abuse of Nature in Catalonia with Proposals for Sustainable Management

land Essay Impacts of Use and Abuse of Nature in Catalonia with Proposals for Sustainable Management Josep Peñuelas 1,2,3,4,* , Josep Germain 2, Enrique Álvarez 3, Enric Aparicio 5, Pere Arús 6, Corina Basnou 3, Cèsar Blanché 7,Núria Bonada 8 , Puri Canals 9, Marco Capodiferro 10 , Xavier Carceller 11, Alexandre Casademunt 12,13 , Joan Casals 14 , Pere Casals 15, Francesc Casañas 14, Jordi Catalán 3,4 , Joan Checa 16 , Pedro J. Cordero 17, Joaquim Corominas 18, Adolf de Sostoa 8, Josep Maria Espelta Morral 3, Marta Estrada 1,19 , Ramon Folch 1,20, Teresa Franquesa 21,22, Carla Garcia-Lozano 23 , Mercè Garí 10,24 , Anna Maria Geli 25, Óscar González-Guerrero 16 , Javier Gordillo 3, Joaquim Gosálbez 1,8, Joan O. Grimalt 1,10 , Anna Guàrdia 3, Rosó Isern 3, Jordi Jordana 26 , Eva Junqué 10,27, Josep Lascurain 28, Jordi Lleonart 19, Gustavo A. Llorente 8 , Francisco Lloret 3,29, Josep Lloret 5 , Josep Maria Mallarach 9,30, Javier Martín-Vide 31 , Rosa Maria Medir 25, Yolanda Melero 3 , Josep Montasell 32, Albert Montori 8, Antoni Munné 33, Oriol Nel·lo 1,16 , Santiago Palazón 34 , Marina Palmero 3, Margarita Parés 21, Joan Pino 3,29 , Josep Pintó 23 , Llorenç Planagumà 13 , Xavier Pons 16 , Narcís Prat 8 , Carme Puig 35, Ignasi Puig 36 , Pere Puigdomènech 1,6, Eudald Pujol-Buxó 8 ,Núria Roca 8 , Jofre Rodrigo 37, José Domingo Rodríguez-Teijeiro 8 , Francesc Xavier Roig-Munar 23, Joan Romanyà 38 , Pere Rovira 15 , Llorenç Sàez 29,39, Maria Teresa Sauras-Yera 8 , David Serrat 1,40, Joan Simó 14, Jordi Soler 41, Jaume Terradas 1,3,29 , Ramon -

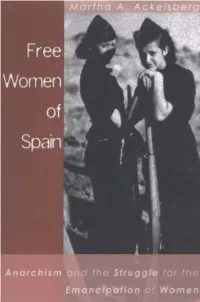

Ackelsberg L

• • I I Free Women of Spain Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women I Martha A. Ackelsberg l I f I I .. AK PRESS Oakland I West Virginia I Edinburgh • Ackelsberg. Martha A. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women Lihrary of Congress Control Numher 2003113040 ISBN 1-902593-96-0 Published hy AK Press. Reprinted hy Pcrmi"inn of the Indiana University Press Copyright 1991 and 2005 by Martha A. Ackelsherg All rights reserved Printed in Canada AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612-1163 USA (510) 208-1700 www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh. EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555-5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] The addresses above would be delighted to provide you with the latest complete AK catalog, featur ing several thousand books, pamphlets, zines, audio products, videos. and stylish apparel published and distributed bv AK Press. A1tern�tiv�l�! Uil;:1t r\llr "-""'l:-,:,i!'?� f2":' �!:::: :::::;:;.p!.::.;: ..::.:.:..-..!vo' :uh.. ,.",i. IIt;W� and updates, events and secure ordering. Cover design and layout by Nicole Pajor A las compafieras de M ujeres Libres, en solidaridad La lucha continua Puiio ell alto mujeres de Iberia Fists upraised, women of Iheria hacia horiz,ontes prePiados de luz toward horizons pregnant with light por rutas ardientes, on paths afire los pies en fa tierra feet on the ground La frente en La azul. face to the blue sky Atirmondo promesas de vida Affimling the promise of life desafiamos La tradicion we defy tradition modelemos la arcilla caliente we moLd the warm clay de un mundo que nace del doLor. -

Coalition Politics in Catalan Local Governments, 1979-2011

Coalition Politics in Catalan Local Governments, 1979-2011 Santi Martínez Farrero ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) i a través del Dipòsit Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX ni al Dipòsit Digital de la UB. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX o al Dipòsit Digital de la UB (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) y a través del Repositorio Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR o al Repositorio Digital de la UB. -

Pluviometric Anomaly in the Llobregat Delta

Tethys, 6, 31–50, 2009 Journal edited by ACAM Journal of Weather & Climate of the Western Mediterranean (Associacio´ Catalana de Meteorologia) www.tethys.cat ISSN-1697-1523 eISSN-1139-3394 DOI:10.3369/tethys.2009.6.03 Pluviometric anomaly in the Llobregat Delta J. Mazon´ 1 and D. Pino1,2 1Department of Applied Physics. Escola Politecnica` Superior de Castelldefels, Universitat Politecnica` de Catalunya. Avda. del Canal Ol´ımpic s/n. 08860 Castelldefels 2Institut d’Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC/CSIC). Barcelona Received: 16-X-2008 – Accepted: 10-III-2009 – Translated version Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract The data from surface automatic weather stations show that in the area of the Llobregat delta (northeast of the Iberian Peninsula) we can observe greater precipitation than in nearby inland areas (Ordal, Collserola, Garraf), than on the other side of a massif located on the coast (Garraf) and than on the northern coast. This distribution of the precipitation could be explained by the formation of a nocturnal surface cold front in the Llobregat delta. In order to analyze in-depth the physical mechanisms that can influence the formation of this front (topography, sea and drainage winds), two rain episodes in the area were simulated with the MM5 mesoscale model, reproducing satisfactorily the physical mechanisms that favor the appearance of the front. Key words: nocturnal land breeze, coastal fronts, precipitation rhythms 1 Introduction which becomes wider when reaching the delta area. Sec- ondly, it is due to the sudden rise of the Garraf massif, in the When two air masses with different temperatures, and westernmost area of the delta, and of Montju¨ıc Mountain to therefore different densities, converge on the surface, as it is the east, both limiting the Llobregat delta, and therefore lim- known, they do not mix, but the warmer and less dense mass iting the cold air that descends the valley during the night. -

A Consortium for Integrated Management and Governance in the Costa Del Garraf - ES

A Consortium for Integrated Management and Governance in the Costa Del Garraf - ES A Consortium for Integrated Management and Governance in the Costa Del Garraf - ES 1. Policy Objective & Theme ADAPTATION TO RISK: Managing impacts of climate change and safeguarding resilience of coasts/coastal systems ADAPTATION TO RISK: Preventing and managing natural hazards and technological (human-made) hazards ADAPTATION TO RISK: Integrating coherent strategies covering the risk-dimension (prevention to response) into planning and investment SUSTAINABLE USE OF RESOURCES: Preserving coastal environment (its functioning and integrity) to share space SUSTAINABLE USE OF RESOURCES: Sound use of resources and promotion of less resource intensive processes/products SUSTAINABLE ECONOMIC GROWTH: Balancing economic, social, cultural development whilst enhancing environment SUSTAINABLE ECONOMIC GROWTH: Improving competitiveness 2. Key Approaches Integration Participation Knowledge-based Ecosystems based approach 3. Experiences that can be exchanged A successful approach for sustainable and integrated coastal management, through the establishment of a local Consortium which includes municipalities, county councils, and the Regional Departments of the Generalitat of Catalonia, to elaborate action plans and specific projects. This initiative is the implementation at the local level of all the European, national and regional ICZM regulations, promoting the co-ordination and co-operation with institutional actors, scientists and social associations. 4. Overview of the case The Consortium was created in 2006 with the aim to sustainably manage a coastal, marine and land area in the county of Garraf, following the European Recommendation on ICZM. It comprises the municipalities of Sitges, Sant Pere de Ribes, Vilanova i Cubelles; Garraf Regional Council and three departments of the Government of Catalonia: Environment and Housing, Agriculture, Food and Rural Action and Country Planning and Public Works. -

Memòria Mapa De Patrimoni Cultural De Cubelles

Memòria mapa de patrimoni cultural Cubelles Tríade Serveis Culturals Novembre 2020 CIF J-61424263 c. Dr. Pasteur, 15, 1r 1a 08720 Vilafranca del Penedès Tel. 93 817 28 68 [email protected] www.triadecultural.com MEMÒRIA DEL MAPA DE PATRIMONI CULTURAL I NATURAL DE CUBELLES (EL GARRAF) Vilafranca del Penedès, novembre de 2020 ÍNDEX 1. METODOLOGIA I CRITERIS DE REALITZACIÓ DEL MAPA DE PATRIMONI CULTURAL ................................................................................................................... 3 2. DIAGNÒSTIC ........................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Marc geogràfic i medi físic ................................................................................... 6 2.1.1 Paisatge........................................................................................................ 6 2.1.2 Clima ............................................................................................................ 8 2.1.3 Geomorfologia .............................................................................................. 9 2.1.4 Vegetació ...................................................................................................... 9 2.1.4 Hidrologia ................................................................................................... 11 2.2 Geografia Humana. Estructura urbana. Economia i poblament ......................... 11 2.3 Síntesi històrica ................................................................................................