A Canadian Perspective on the International Film Festival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Sexploitation to Canuxploitation (Representations of Gender in the Canadian ‘Slasher’ Film)

Maple Syrup Gore: From Sexploitation to Canuxploitation (Representations of Gender in the Canadian ‘Slasher’ Film) by Agnieszka Mlynarz A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Theatre Studies Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Agnieszka Mlynarz, April, 2017 ABSTRACT Maple Syrup Gore: From Sexploitation to Canuxploitation (Representations of Gender in the Canadian ‘Slasher’ Film) Agnieszka Mlynarz Advisor: University of Guelph, 2017 Professor Alan Filewod This thesis is an investigation of five Canadian genre films with female leads from the Tax Shelter era: The Pyx, Cannibal Girls, Black Christmas, Ilsa: She Wolf of the SS, and Death Weekend. It considers the complex space women occupy in the horror genre and explores if there are stylistic cultural differences in how gender is represented in Canadian horror. In examining variations in Canadian horror from other popular trends in horror cinema the thesis questions how normality is presented and wishes to differentiate Canuxploitation by defining who the threat is. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Dr. Paul Salmon and Dr. Alan Filewod. Alan, your understanding, support and above all trust in my offbeat work ethic and creative impulses has been invaluable to me over the years. Thank you. To my parents, who never once have discouraged any of my decisions surrounding my love of theatre and film, always helping me find my way back despite the tears and deep- seated fears. To the team at Black Fawn Distribution: Chad Archibald, CF Benner, Chris Giroux, and Gabriel Carrer who brought me back into the fold with open arms, hearts, and a cold beer. -

Download File

Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 Eileen Ryan Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 ©2012 Eileen Ryan All rights reserved ABSTRACT Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 By Eileen Ryan In the first decade of their occupation of the former Ottoman territories of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in current-day Libya, the Italian colonial administration established a system of indirect rule in the Cyrenaican town of Ajedabiya under the leadership of Idris al-Sanusi, a leading member of the Sufi order of the Sanusiyya and later the first monarch of the independent Kingdom of Libya after the Second World War. Post-colonial historiography of modern Libya depicted the Sanusiyya as nationalist leaders of an anti-colonial rebellion as a source of legitimacy for the Sanusi monarchy. Since Qaddafi’s revolutionary coup in 1969, the Sanusiyya all but disappeared from Libyan historiography as a generation of scholars, eager to fill in the gaps left by the previous myopic focus on Sanusi elites, looked for alternative narratives of resistance to the Italian occupation and alternative origins for the Libyan nation in its colonial and pre-colonial past. Their work contributed to a wider variety of perspectives in our understanding of Libya’s modern history, but the persistent focus on histories of resistance to the Italian occupation has missed an opportunity to explore the ways in which the Italian colonial framework shaped the development of a religious and political authority in Cyrenaica with lasting implications for the Libyan nation. -

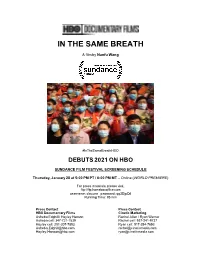

In the Same Breath

IN THE SAME BREATH A film by Nanfu Wang #InTheSameBreathHBO DEBUTS 2021 ON HBO SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL SCREENING SCHEDULE Thursday, January 28 at 5:00 PM PT / 6:00 PM MT – Online (WORLD PREMIERE) For press materials, please visit: ftp://ftp.homeboxoffice.com username: documr password: qq3DjpQ4 Running Time: 95 min Press Contact Press Contact HBO Documentary Films Cinetic Marketing Asheba Edghill / Hayley Hanson Rachel Allen / Ryan Werner Asheba cell: 347-721-1539 Rachel cell: 937-241-9737 Hayley cell: 201-207-7853 Ryan cell: 917-254-7653 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] LOGLINE Nanfu Wang's deeply personal IN THE SAME BREATH recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. SHORT SYNOPSIS IN THE SAME BREATH, directed by Nanfu Wang (“One Child Nation”), recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. In a deeply personal approach, Wang, who was born in China and now lives in the United States, explores the parallel campaigns of misinformation waged by leadership and the devastating impact on citizens of both countries. Emotional first-hand accounts and startling, on-the-ground footage weave a revelatory picture of cover-ups and misinformation while also highlighting the strength and resilience of the healthcare workers, activists and family members who risked everything to communicate the truth. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT I spent a lot of my childhood in hospitals taking care of my father, who had rheumatic heart disease. -

News Release

News Release For immediate release (All figures are in Cdn$, unless otherwise indicated) BCE REPORTS 2004 YEAR-END AND FOURTH QUARTER RESULTS Montréal, Québec, February 2, 2005 — For the full year 2004 BCE Inc. (TSX, NYSE: BCE) reported revenue of $19.2 billion, up 2.4 per cent and EBITDA1 of $7.6 billion, an increase of 2.1 per cent over the full year 2003. For the fourth quarter of 2004, the company reported revenue of $5.0 billion, up 3.5 per cent, and EBITDA of $1.8 billion, down 0.9 per cent when compared to the same period last year. In 2004, before restructuring BCE achieved its free cash flow2 target of approximately $1 billion and earnings per share (EPS)3 of $2.02 which was up 6.3 per cent. “The past year was important for BCE as we laid the foundation to position Bell Canada for a new era of communications,” said Michael Sabia, President and Chief Executive Officer of BCE Inc. “We delivered on our key strategic initiatives and met our guidance for financial performance in 2004. Overall, our progress in the year gives us confidence in the forward momentum of the company as outlined at our annual investor conference in mid- December.” The company’s performance in 2004 and the outlook for 2005 and beyond were among the factors that led BCE in December to increase its common share annual dividend by $0.12, or 10 per cent. In the fourth quarter, the company’s revenue growth rate continued to improve. The quarter saw continued subscriber growth in wireless, video and DSL. -

To Utopianize the Mundane: Sound and Image in Country Musicals Siyuan Ma

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 3-23-2016 To Utopianize the Mundane: Sound and Image in Country Musicals Siyuan Ma Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ma, Siyuan, "To Utopianize the Mundane: Sound and Image in Country Musicals" (2016). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6112 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To Utopianize the Mundane: Sound and Image in Country Musicals by (Max) Siyuan Ma A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a concentration in Film and New Media Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Andrew Berish, Ph.D. Amy Rust, Ph.D. Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 1, 2016 Keywords: country music, utopia, authenticity, community, country musical, Pure Country Copyright © 2016, (Max) Siyuan Ma Dedication To Judy Seale, Phil and Elisabeth Pearson, Eddie Heinzelman, and those who offered me thoughts and reflections on country music in music stores and banjo shops in Florida, New York, and Pennsylvania. Yo-Yo Ma, and those who care about music and culture and encourage humanistic thinking, feeling and expressing. Hao Lee, Bo Ma, and Jean Kuo. -

Missions and Film Jamie S

Missions and Film Jamie S. Scott e are all familiar with the phenomenon of the “Jesus” city children like the film’s abused New York newsboy, Little Wfilm, but various kinds of movies—some adapted from Joe. In Susan Rocks the Boat (1916; dir. Paul Powell) a society girl literature or life, some original in conception—have portrayed a discovers meaning in life after founding the Joan of Arc Mission, variety of Christian missions and missionaries. If “Jesus” films while a disgraced seminarian finds redemption serving in an give us different readings of the kerygmatic paradox of divine urban mission in The Waifs (1916; dir. Scott Sidney). New York’s incarnation, pictures about missions and missionaries explore the East Side mission anchors tales of betrayal and fidelity inTo Him entirely human question: Who is or is not the model Christian? That Hath (1918; dir. Oscar Apfel), and bankrolling a mission Silent movies featured various forms of evangelism, usually rekindles a wealthy couple’s weary marriage in Playthings of Pas- Protestant. The trope of evangelism continued in big-screen and sion (1919; dir. Wallace Worsley). Luckless lovers from different later made-for-television “talkies,” social strata find a fresh start together including musicals. Biographical at the End of the Trail mission in pictures and documentaries have Virtuous Sinners (1919; dir. Emmett depicted evangelists in feature films J. Flynn), and a Salvation Army mis- and television productions, and sion worker in New York’s Bowery recent years have seen the burgeon- district reconciles with the son of the ing of Christian cinema as a distinct wealthy businessman who stole her genre. -

68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan A

Specters of '68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Galen Cranz, Chair Professer C. Greig Crysler Professor Richard Walker Summer 2015 Sagan Copyright page Sagan Abstract Specters of '68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Galen Cranz, Chair Political protest is an increasingly frequent occurrence in urban public space. During times of protest, the use of urban space transforms according to special regulatory circumstances and dictates. The reorganization of economic relationships under neoliberalism carries with it changes in the regulation of urban space. Environmental design is part of the toolkit of protest control. Existing literature on the interrelation of protest, policing, and urban space can be broken down into four general categories: radical politics, criminological, technocratic, and technical- professional. Each of these bodies of literature problematizes core ideas of crowds, space, and protest differently. This leads to entirely different philosophical and methodological approaches to protests from different parties and agencies. This paper approaches protest, policing, and urban space using a critical-theoretical methodology coupled with person-environment relations methods. This paper examines political protest at American Presidential National Conventions. Using genealogical-historical analysis and discourse analysis, this paper examines two historical protest event-sites to develop baselines for comparison: Chicago 1968 and Dallas 1984. Two contemporary protest event-sites are examined using direct observation and discourse analysis: Denver 2008 and St. -

Broadcasting Taste: a History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media a Thesis in the Department of Co

Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media A Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2016 © Zoë Constantinides, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Zoë Constantinides Entitled: Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Communication Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: __________________________________________ Beverly Best Chair __________________________________________ Peter Urquhart External Examiner __________________________________________ Haidee Wasson External to Program __________________________________________ Monika Kin Gagnon Examiner __________________________________________ William Buxton Examiner __________________________________________ Charles R. Acland Thesis Supervisor Approved by __________________________________________ Yasmin Jiwani Graduate Program Director __________________________________________ André Roy Dean of Faculty Abstract Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media Zoë Constantinides, -

Minding the Gap : a Rhetorical History of the Achievement

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Minding the gap : a rhetorical history of the achievement gap Laura Elizabeth Jones Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Laura Elizabeth, "Minding the gap : a rhetorical history of the achievement gap" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3633. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3633 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. MINDING THE GAP: A RHETORICAL HISTORY OF THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Laura Jones B.S., University of Colorado, 1995 M.S., Louisiana State University, 2010 August 2013 To the students of Glen Oaks, Broadmoor, SciAcademy, McDonough 35, and Bard Early College High Schools in Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana ii Acknowledgements I am happily indebted to more people than I can name, particularly members of the Baton Rouge and New Orleans communities, where countless students, parents, faculty members and school leaders have taught and inspired me since I arrived here in 2000. I am happy to call this complicated and deeply beautiful community my home. -

News Release

News Release BCE Reaches Definitive Agreement to be Acquired By Investor Group Led by Teachers, Providence and Madison BCE Board Recommends Shareholders Accept C$42.75 (US$40.13) Per Share Offer • Offer is 40% premium over “undisturbed share price” • Closing targeted for first quarter, 2008 MONTREAL, Quebec, June 30, 2007 – BCE (TSX/NYSE: BCE) today announced that the company has entered into a definitive agreement for BCE to be acquired by an investor group led by Teachers Private Capital, the private investment arm of the Ontario Teachers Pension Plan, Providence Equity Partners Inc. and Madison Dearborn Partners, LLC. The all-cash transaction is valued at C$51.7 billion (US$48.5 billion), including C$16.9 billion (US$15.9 billion) of debt, preferred equity and minority interests. The BCE Board of Directors unanimously recommends that shareholders vote to accept the offer. Under the terms of the transaction, the investor group will acquire all of the common shares of BCE not already owned by Teachers for an offer price of C$42.75 per common share and all preferred shares at the prices set forth in the attached schedule. Financing for the transaction is fully committed through a syndicate of banks acting on behalf of the purchaser. The purchase price represents a 40% premium over the undisturbed average trading price of BCE common shares in the first quarter of 2007, prior to the possibility of a privatization transaction surfacing publicly. The transaction values BCE at 7.8 times EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) for the 12-month period ending March 31, 2007. -

Film Festival 2008

THE LEO AWARDS and PACIFIC CINÉMATHÈQUE proudly present TALKBACK A FILM ARTIST SALON WITH LEO AWARDS 2008 NOMINEES FILM FESTIVAL 2008 THURSDAY, MAY 22 @ CINEMA 319 at PACIFIC CINÉMATHÈQUE Join First Weekend Club for an evening of intimate The Leo Awards, the annual celebration of excellence in made-in-B.C. film and television, were established in conversations with some of BC’s finest filmmaking talent 1998 to honour the best of B.C. film and television, and are presented each year at a gala awards ceremony. at the the swanky Cinema 319 at 319 Main Street. Since 2003, they have been a project of the Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Foundation of British Columbia, a non-profit society formed to celebrate and promote the achievements of the B.C. film and television industry. Keep your movie ticket stub from any of the Leo Award Film Festival screenings at Pacific Cinémathèque and your THURSDAY, MAY 15 admission fee to the Talkback will be waived. The Leo Awards Film Festival provides an opportunity for members of the general public to share in the impressive FEATURE LENGTH DRAMA accomplishments of our B.C. filmmakers. Public screening of this year’s Leo Awards nominees in several program Visit www.firstweekendclub.ca for event details and categories — encompassing features, documentaries, short dramas, and student productions — will be presented updates on featured guests. FRIDAY, MAY 16 over five days, May 15-19, at Pacific Cinémathèque. The 10th Annual Leo Awards Celebration and Gala Awards DOCUMENTARY Ceremony will take place the following weekend, May 23 & 24, at the Westin Bayshore Vancouver. -

2018-2015 BC Master Production Agreement

2015-2018 BRITISH COLUMBIA PMRAODSUTCTEIOR N AGREEMENT 300 - 380 West 2nd Avenue Vancouver, BC V5Y 1C8 p 604.689.0727 f 604.689.1145 [email protected] www.ubcp.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Preamble ...................................................................................................................................... 1 SECTION A - GENERAL CLAUSES..................................................................................... 1 ARTICLE A1 - UNION RECOGNITION AND APPLICATION ........................................... 1 Union Recognition .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Scope of Agreement........................................................................................................................................ 1 Future Negotiations on Scope of Agreement ................................................................................................. 1 Minimum Terms ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Agreement in Whole ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Rights of Producer .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Laws of British Columbia Apply ..................................................................................................................