Minding the Gap : a Rhetorical History of the Achievement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Same Breath

IN THE SAME BREATH A film by Nanfu Wang #InTheSameBreathHBO DEBUTS 2021 ON HBO SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL SCREENING SCHEDULE Thursday, January 28 at 5:00 PM PT / 6:00 PM MT – Online (WORLD PREMIERE) For press materials, please visit: ftp://ftp.homeboxoffice.com username: documr password: qq3DjpQ4 Running Time: 95 min Press Contact Press Contact HBO Documentary Films Cinetic Marketing Asheba Edghill / Hayley Hanson Rachel Allen / Ryan Werner Asheba cell: 347-721-1539 Rachel cell: 937-241-9737 Hayley cell: 201-207-7853 Ryan cell: 917-254-7653 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] LOGLINE Nanfu Wang's deeply personal IN THE SAME BREATH recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. SHORT SYNOPSIS IN THE SAME BREATH, directed by Nanfu Wang (“One Child Nation”), recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. In a deeply personal approach, Wang, who was born in China and now lives in the United States, explores the parallel campaigns of misinformation waged by leadership and the devastating impact on citizens of both countries. Emotional first-hand accounts and startling, on-the-ground footage weave a revelatory picture of cover-ups and misinformation while also highlighting the strength and resilience of the healthcare workers, activists and family members who risked everything to communicate the truth. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT I spent a lot of my childhood in hospitals taking care of my father, who had rheumatic heart disease. -

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

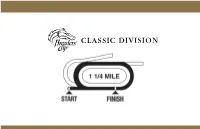

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

204 Longways Stables 204

204 Longways Stables 204 Empire Maker Pioneerof The Nile AMERICAN Star of Goshen PHAROAH Yankee Gentleman Littleprincessemma N. (USA) Exclusive Rosette Storm Cat chesnut filly 23/03/2018 Giant's Causeway ADESTE FIDELES Mariah's Storm 2011 (USA) Imagine Sadler's Wells 1998 Doff The Derby E.B.F./B.C. Nominated AMERICAN PHAROAH (2012), 9 wins at 2 and 3 years, Breeders' Cup Classic (Gr.1). Stud in 2016. Sire of FOUR WHEEL DRIVE, Breeders' Cup Juvenile Turf Sprint, Gr.2, SWEET MELANIA, Jessamine S., Gr.2, MAVEN, Prix du Bois, Gr.3, CAFE PHAROAH, Hyacinth S., L., HARVEY'S LIL GOIL, Busanda S., ANOTHER MIRACLE, Skidmore S., American Theorem, Monarch of Egypt. 1st dam ADESTE FIDELES, 1 win, pl. 3 times at 3 years in IRE. Own sister to VISCOUNT NELSON and POINT PIPER. Dam of : N., (see above), her 2nd foal. 2nd dam IMAGINE, 4 wins at 2 and 3 years in GB and IRE, Irish 1000 Guineas (Gr.1), Oaks S.(Gr.1), C. L. Weld Park S.(Gr.3), 2nd Rockfel S.(Gr.2), £382,032. Own sister to STRAWBERRY ROAN. Dam of 12 foals of racing age, 9 winners incl. : HORATIO NELSON (c., Danehill), 4 wins at 2 years in FR, IRE & GB, Prix Jean-Luc Lagardère (Gr.1), Futurity S.(Gr.2), Superlative S.(Gr.3), 2nd Dewhurst S.(Gr.1), £284,236. VISCOUNT NELSON (c., Giant's Causeway), 4 wins at 2 to 5 in IRE & UAE, Al Fahidi Fort S.(Gr.2), 2nd Champagne S.(Gr.2), 3rd Irish 2000 Guineas (Gr.1), Eclipse S.(Gr.1), £465,391. -

A Canadian Perspective on the International Film Festival

NEGOTIATING VALUE: A CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE ON THE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL by Diane Louise Burgess M.A., University ofBritish Columbia, 2000 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the School ofCommunication © Diane Louise Burgess 2008 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2008 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or by other means, without permission ofthe author. APPROVAL NAME Diane Louise Burgess DEGREE PhD TITLE OF DISSERTATION: Negotiating Value: A Canadian Perspective on the International Film Festival EXAMINING COMMITTEE: CHAIR: Barry Truax, Professor Catherine Murray Senior Supervisor Professor, School of Communication Zoe Druick Supervisor Associate Professor, School of Communication Alison Beale Supervisor Professor, School of Communication Stuart Poyntz, Internal Examiner Assistant Professor, School of Communication Charles R Acland, Professor, Communication Studies Concordia University DATE: September 18, 2008 11 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Minding the Body Interacting Socially Through Embodied Action

Linköping Studies in Science and Technology Dissertation No. 1112 Minding the Body Interacting socially through embodied action by Jessica Lindblom Department of Computer and Information Science Linköpings universitet SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden Linköping 2007 © Jessica Lindblom 2007 Cover designed by Christine Olsson ISBN 978-91-85831-48-7 ISSN 0345-7524 Printed by UniTryck, Linköping 2007 Abstract This dissertation clarifies the role and relevance of the body in social interaction and cognition from an embodied cognitive science perspective. Theories of embodied cognition have during the past two decades offered a radical shift in explanations of the human mind, from traditional computationalism which considers cognition in terms of internal symbolic representations and computational processes, to emphasizing the way cognition is shaped by the body and its sensorimotor interaction with the surrounding social and material world. This thesis develops a framework for the embodied nature of social interaction and cognition, which is based on an interdisciplinary approach that ranges historically in time and across different disciplines. It includes work in cognitive science, artificial intelligence, phenomenology, ethology, developmental psychology, neuroscience, social psychology, linguistics, communication, and gesture studies. The theoretical framework presents a thorough and integrated understanding that supports and explains the embodied nature of social interaction and cognition. It is argued that embodiment is the part and parcel of social interaction and cognition in the most general and specific ways, in which dynamically embodied actions themselves have meaning and agency. The framework is illustrated by empirical work that provides some detailed observational fieldwork on embodied actions captured in three different episodes of spontaneous social interaction in situ. -

4Th MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE

th 4 MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, 17 TO 24 JANUARY, 2018 SOCIAL PROGRAMME: ROYAL PEDREGAL HOTEL ACADEMIC PROGRAMME: NATIONAL AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO Auditorio Alfonso Caso and Anexos de la Facultad de Derecho FINAL PROGRAMME (Online version linked to abstracts. Download PDF here) 1/47 All delegates please note: 1. Presentation slots may have needed to be moved by the organisers, and may appear in a different place from that of the final printed programme. Please consult the schedule located in the Conference Programme upon arrival at the Conference for your presentation time. 2. Please note that presenters have to ensure the following times for presentation to allow for adequate time for questions from the floor and smooth transition of sessions. Delegates must not stray from their allocated 20 minutes. Further, delegates are welcome to move within sessions, therefore presenters MUST limit their talk to the allocated time. Therefore, Q&A will be AFTER each talk, and NOT at the end of the three presentations. Plenary and Invited Talks – 45 min. presentation and 15 min. discussion (Q&A). 3. For panels, each panellist must stick strictly to a 10 minute time frame, before discussion with the floor commences. 4. Note that co-authors may be presenting at the conference in place of, or with the main author. For all co-authors, delegates are advised to consult the Conference Abstracts link on the Minding Animals website. Use of the term et al is provided where there is more than two authors of an abstract. 5. Moderator notes will be available at all front desks in tutorial rooms, along with Time Sheets (5, 3 and 1 minute Left). -

A Canadian Perspective on the International Film Festival

NEGOTIATING VALUE: A CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE ON THE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL by Diane Louise Burgess M.A., University ofBritish Columbia, 2000 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the School ofCommunication © Diane Louise Burgess 2008 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2008 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or by other means, without permission ofthe author. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-58719-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-58719-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. -

Starz’S €˜America to Me’ Docuseries Explores Race in Schools

Starz’s ‘America to Me’ Docuseries Explores Race in Schools 06.29.2018 Filmmaker Steve James (Hoop Dreams, The Interrupters, Life Itself, Abacus: Small Enough to Jail) spent a year inside suburban Chicago's Oak Park and River Forest High School, exploring the grapple with decades-long racial and educational inequities. America to Me follows students, teachers and administrators at one of the country's highest performing and diverse public schools, digging into many of the stereotypes and challenges that today's teenagers face, and looking at what has succeeded and failed in the quest to achieve racial equality in our educational system. The 10-part series also serves as the launch of a social impact campaign focusing on the issues highlighted in each episode. Starz partnered with series producer Participant Media to encourage candid conversations about racism through a downloadable Community Conversation Toolkit and elevate student voices through a national spoken-word poetry contest. Alongside the release of each new episode, the campaign will also host a high-profile screening event in one city across the country. Over the course of 10 weeks, these 10 events will seed a national dialogue anchored by the series, and kick off activities across the country to inspire students, teachers, parents and community leaders to develop local initiatives that address inequities in their own communities, says Starz. James directed and executive produced the series, along with executive producers Gordon Quinn (The Trials of Muhammad Ali), Betsy Steinberg (Edith+Eddie) and Justine Nagan (Minding the Gap) at his longtime production home, Kartemquin Films. -

Doc Nyc Unveils Influential Short Lists

DOC NYC UNVEILS INFLUENTIAL SHORT LISTS FOR FEATURES & SHORTS PLUS INAUGURAL “WINNER’S CIRCLE” SECTION, LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT SCREENINGS, “40 UNDER 40” LIST AND NEW AWARDS NEW YORK, September 26, 2019 - DOC NYC, America’s largest documentary festival, celebrating its 10th anniversary, announced the lineup for three of its most prestigious sections. Short List: Features and Short List: Shorts each curate a selection of nonfiction films that the festival’s programming team considers to be among the year’s strongest contenders for Oscars and other awards. For the first time, the Short List: Features will vie for juried awards in four categories: Directing, Producing, Cinematography and Editing, and a Best Director prize will also be awarded in the Short List: Shorts section. The festival also announced the launch of a new section, Winner’s Circle, highlighting films that have won top prizes at international festivals, but might fly below the radar of American audiences. Michael Apted and Martin Scorsese, the two recipients of DOC NYC’s previously announced Visionaries Lifetime Achievement Awards, will also have their latest documentary films screened: 63 Up and Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese, respectively. The festival also announced the second year of its 40 Under 40 list of young rising stars in the documentary community, co-presented by Topic Studios. “Today’s announcements of the DOC NYC Short Lists, Winner’s Circle and 40 Under 40 showcase a tremendous breadth and depth of talent,” said festival Artistic Director Thom Powers. “We’re excited to bring New York audiences to some of the year’s best films and showcase the future of the documentary field.” AMPAS members can email [email protected] to register for a Short List Pass to gain free admission to Short List, Winner’s Circle and Lifetime Achievement screenings; as well as to the panel discussions for Short List: Features (Fri, Nov. -

Ancient Skiers Book 2014

Second Edition - 2014 INTRODUCTION When I was asked if I would write the history of the Ancient Skiers, I was excited and willing. My husband, Jim, and I were a part of those early skiers during those memorable times. We had “been there and done that” and it was time to put it down on paper for future generations to enjoy. Yes, we were a part of The Ancient Skiers and it is a privilege to be able to tell you about them and the way things were. Life was different - and it was good! I met Jim on my first ski trip on the Milwaukee Ski Train to the Ski Bowl in 1938. He sat across the aisle and had the Sunday funnies - I had the cupcakes - we made a bond and he taught me to ski. We were married the next year. Jim became Certified as a ski instructor at the second certification exam put on by the Pacific Northwest Ski Association (PNSA) in 1940, at the Ski Bowl. I took the exam the next year at Paradise in 1941, to become the first woman in the United States to become a Certified Ski Instructor. Skiing has been my life, from teaching students, running a ski school, training instructors, and most of all being the Executive Secretary for the Pacific Northwest Ski Instructors Association (PNSIA) for over 16 years. I ran their Symposiums for 26 years, giving me the opportunity to work with many fine skiers from different regions as well as ski areas. Jim and I helped organize the PNSIA and served on their board for nearly 30 years. -

07-12-2021 WIF and the Sundance Institute Financing

July 12, 2021 Media Contacts: Spencer Alcorn [email protected] Women’s Financing Intensive, from WIF (Women In Film, Los Angeles) & Sundance Institute, Elevates Twelve Feature Projects with Tailored Support Intensive equips filmmakers with financing strategies and introduces them to leading financiers. LOS ANGELES - The Sundance Institute and WIF (Women In Film, Los Angeles) today announce the projects and creators selected for the annual WIF and Sundance Institute Financing Intensive. The Intensive is designed to help women producers—fiction and documentary—build the skills and relationships necessary to advance a feature-length project to the next stage of financing success. On July 14–15, producers and their attached directors participate in small group workshops focused on both pitching and financing strategy, and professional skills development. The Intensive continues the week of July 19 with one-on-one meetings with potential financiers and partners including The Harnisch Foundation, IDA, Impact Partners, Participant, Freeform, Hulu, Gamechanger, Chicken & Egg Pictures, K Period. The Intensive will first kick off with a free public session on July 13 at 2pm – 3:15pm ET, Protecting Producers, that will explore fresh ideas in producer career sustainability. The conversation will take place on Sundance Co//ab and include: Carrie Lozano (Director, Sundance Documentary Film Program and Artist Programs), Yael Melamede (Documentary Producers Alliance), producer Summer Shelton, and Avril Speaks (Producers Union). The Institute and WIF have been working together to address the most challenging obstacles facing women filmmakers at both structural and project-based levels. Accessing capital remains elusive even for seasoned creators, and research by both institutions has shown that women continue to deal with particular gendered biases that make it harder to secure financing. -

Mirror Lake: Beauty & History Imagine Getting Paid for Your Hobby

Lynn Lotkowictz Lynn St. Petersburg, FL MAR/APR 2021 Est. September 2004 Imagine Getting Paid Changing Lives With for Your Hobby the Red Tent Initiative –– JANAN TALAFER –– ometimes a simple synchronicity can be life-changing in ways we couldn’t dream of at the time. That’s what happened Sfor Barbara Rhode, a St. Petersburg licensed marriage and family therapist and founder of the Red Tent Women’s Initiative. Barbara had just finished reading Anita Diamant’s book, The Red Tent – a compelling fiction about the ancient tradition of women seeking comfort in each other’s company while they spent time in the “red tent.” The book reinforced Barbara’s belief that for many women, having a safe space to share their feelings and experiences was very much missing in today’s society. John and Lien Satino with their dog Mino out for a drive in the vintage Edsel –– SAMANTHA BOND RICHMAN –– magine getting paid for your hobby. Shore Acres resident John Satino does just that. He’s a car guy from way back in his childhood, hanging out in his stepdad’s garage, and later fixing cars Ineeding a lot of work, which he bought from the ‘back lot’ of the local Chevy dealership and then sold for a profit. He was changing out engines and transmissions even before he had his driver’s license in his original state of Ohio. Since 1984, his car collection has been featured in numerous television and movie productions, sometimes generating a nice daily stipend, though clearly John would collect cars with or without the added attention.