Class, Culture and Conflict in Barcelona 1898–1937

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

El Posicionament Colonialista D'enric Prat De La Riba I Les

Associació Recerques. Història, Economia, Cultura ISSN 0210-380X Recerques 62 (2011) 117-150 El posicionament colonialista d’Enric Prat de la Riba i les guerres del Marroc Enric Prat de la Riba’s colonialist outlook and the Morocco wars per Eloy Martín Corrales RESUM: ABSTRACT: Per raons d’índole purament ideològica, For purely ideological reasons, much bona part de la historiografia catalana (la do- of Catalan history (the mainstream one, minant, encara que no la de més gran quali- though not the best) has tended to regard tat) ha tendit a considerar que l’ideòleg més the most important ideologist of moderate important del nacionalisme moderat, Enric nationalism, Enric Prat de la Riba, as indiffe- Prat de la Riba, era aliè als postulats coloni- rent to the colonialist ideas so widespread alistes tan estesos per l’Europa de finals del throughout late nineteenth and early twen- segle XIX i començaments del XX. No obs- tieth-century Europe. An exhaustive analy- tant això, l’exhaustiu anàlisi de la seva obra sis of his published work, however, allows publicada permet afirmar taxativament que the author to affirm that Prat was without Prat de la Riba era un clar abanderat del colo- a doubt a champion of colonialism. This nialisme. Això explica que, malgrat les seves explains why, despite his misgivings about diferències amb l’activitat colonial espanyola, some aspects of Spanish colonial activity, he acabés donant suport resoludament a la in- strongly supported in the event the Spanish tervenció de l’exèrcit espanyol al Marroc. army’s intervention in Morocco. PARAULES CLAU: KEYWORDS: Colonialisme, Prat de la Riba, naciona- Colonialism, Prat de la Riba, nationalism, lisme, Marroc. -

Simone Weil: an Anthology

PENGUIN � CLASSICS SIMONE WElL : AN AN THOL OGY SIMONE WElL (1909-1 943) is one of the most important thinkers of the modern period. The distinctive feature of her work is the indissoluble link she makes between the theory and practice of both politics and religion and her translation of thought into action . A brilliant philosopher and mathematician, her life rep resents a quest for justice and balance in both the academic and the practical spheres. A scholar of deep and wide erudition, she became during the thirties an inspired teacher and activist. So as to experience physical labour at first hand, she spent almost two years as a car factory worker soon after the Front Populaire and later became a fighterin the Spanish Civil War. When her home city of Paris was occupied, she joined the Resistance in the South of France and became for a time an agricultural labourer before acceding to her parents' wish to escape Nazi persecution of the Jews by fleeing to New York. Leaving America, she joined the Free French in London where, frustrated by the exclusively intellectual nature of the work delegated to her, and weakened by a number of physical and emotional factors, she contracted tuberculosis and died in a Kentish sanatorium at the age of thirty-four. The bulk of her voluminous oeuvre was published posthumously. SIAN MILES was born and brought up in the bi-cultural atmos phere of Wales and educated there and in France where she has lived for many years. She has taught at a number of universities worldwide, including Tufts University, Massachusetts, Dakar University, Senegal and York University, Toronto. -

Humanizing Streets the Superblocks in the Eixample, Barcelona

HUMANIZING STREETS THE SUPERBLOCKS IN THE EIXAMPLE, BARCELONA Pamela AcuÑA Kuchenbecker Msc Thesis LanDscape Architecture WAGeninGen UniVersitY October 2019 HUMANIZING STREETS THE SUPERBLOCKS IN THE EIXAMPLE, BARCELONA Pamela ANDrea AcuÑA Kuchenbecker Msc Thesis LanDscape Architecture WAGeninGen UniVersitY October 2019 © Pamela Acuña Kuchenbecker Chair Group Landscape Architecture Wageningen University October 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of either the author or the Wageningen University Landscape Architecture Chairgroup. Pamela Andrea Acuña Kuchenbecker Registration number: 111184005150 [email protected] LAR-80436/39 Master Thesis Landscape Architecture Chair Group Landscape Architecture Phone: +31 317 484 056 Fax: +31 317 482 166 E-mail: [email protected] www.lar.wur.nl Postbus 47 6700 AA, Wageningen The Netherlands Examiner Dr. ir. Rudi van Etteger MA Wageningen University, Landscape Architecture group Supervisor & examiner Dr. dipl. ing. Sanda Lenzholzer Wageningen University, Landscape Architecture group Humanizing streets ABSTRACT People’s behavior is affected by the combination of sight, Therefore, the purpose of this thesis is to generate sounds, smells, textures, tastes, and thermal conditions, knowledge for the intersections of superblocks, which can determine how long a place will be used. The which present a deficiency in providing citizens with built environment, due to its population growth over the a comfortable and positive sensory experience. This centuries and with its consequent reduction of green thesis fills the knowledge gap by inferring a new multi- urban areas, has deprived citizens of many pleasures and sensory approach, which aims towards a pleasurable introduced new unpleasant sensations. -

21-467-Planol Plegable Caraa Agost 2021

Sant Genís Cementiri de Collserola Cementiri de Collserola Montcada i Reixac Ciutat Meridiana Ciutat Meridiana C Pl. Parc de Ciutat Meridiana Funicular t 112 Barris Zona 97 r 112 Velòdrom Horta Torre Baró a Sant 185 102 de Vallvidrera . 112 Montbau la Vall 185 Nord d Genís Mpal. d’Horta 183 62 96 e 19 76 Ctra. Horta 182 Vallbona S 112 d’Hebron 18 Peu del Funicular t. a Cerdanyola 3 u C 97 0 e 183 l u a 8 l 19 r g 76 Sant Genís 1 a r e a r a t Transports d 183 C i v Pl. 76 V21 l Lliçà n l 76 Bellprat 0 a Meguidó s 8 a Parc de a de le te Av. Escolapi CàncerTorre Baró Torre Baró 83 1 V t e 1 C Mundet l s u Metropolitans Hospital Universitari 135 A Roq Vallbona e La Font 102 Ronda de Dalt C tra. d Sinaí 76 de la Vall d’Hebron Arquitecte Moragas e r del Racó M19 Can Marcet D50 104 d Rda. Guineueta Vella o j Sarrià Vall d’Hebron 135 Pl. Valldaura a 60 de Barcelona Pg. Sta. Eulàlia C Montbau Pg. Valldaura Metro Roquetes Parc del Llerona 96 35 M o 9 1 Botticelli Roquetes 97 . llse M1 V23 Canyelles / 47 V7 v rola Vall d’Hebron 135 185 Pla de Fornells A 119 Vall d’Hebron V27 Canyelles ya 27 R 180 104 o 196 Funicular M19 n Pl. 127 o 62 ibidab 60 lu C drig . T del Tibidabo 102 ta Porrera de Karl 185 Canyelles 47 a o B v a Canyelles ro alenyà 130 A C Marx sania Can Caralleu Eduard Toda Roquetes A rte Sant Just Desvern 35 G e 1 d r Campoamor a r t Barri de la Mercè Parc del n e u V3 Pl. -

Bolstering Community Ties and Its Effect on Crime

Bolstering community ties and its effect on crime: Evidence from a quasi-random experiment Magdalena Dom´ınguez and Daniel Montolio∗ Work in progress - Do not cite without permission This version: February 2019 Abstract In this paper we study the effect of bolstering community ties on local crime rates. To do so, we take advantage of the quasi-random nature of the implementation of a community health policy in the city of Barcelona. Salut als Barris (BSaB) is a policy that through community-based initiatives and empowerment of citizenship aims at improving health outcomes and reducing inequalities of the most disadvantaged neighborhoods. Based on economic and sociological literature it is also arguable that it may affect other relevant variables for overall welfare, such as crime rates. In order to test such a hypothesis, we use monthly data at the neighborhood level and a staggered Differences-in-Differences approach. Overall we find that BSaB highly reduces crimes related to non-cognitive features as well as those where there is a very close personal link (labeled as home crimes), with responses ranging from 9% to 18%. Additionally, female victimization rates drop for all age groups as well as the offense rates of younger cohorts. We argue that such outcomes are due to stronger community ties. Such results provide evidence in favor of non-traditional crime preventing policies. Keywords: crime; community action; differences-in-differences. JEL codes: C23, I18, I28, J18. ∗Dept. of Economics, University of Barcelona and IEB: [email protected] ; [email protected] We are grateful to Elia Diez and Maribel Pasarin at the Barcelona Public Health Agency (ASPB) and IGOP researchers Raquel Gallego and Ernesto Morales at Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) for their insightful comments on the program. -

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939 Sam Dolgoff (editor) 1974 Contents Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introductory Essay by Murray Bookchin 9 Part One: Background 28 Chapter 1: The Spanish Revolution 30 The Two Revolutions by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 30 The Bolshevik Revolution vs The Russian Social Revolution . 35 The Trend Towards Workers’ Self-Management by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 36 Chapter 2: The Libertarian Tradition 41 Introduction ............................................ 41 The Rural Collectivist Tradition by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 41 The Anarchist Influence by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 44 The Political and Economic Organization of Society by Isaac Puente ....................................... 46 Chapter 3: Historical Notes 52 The Prologue to Revolution by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 52 On Anarchist Communism ................................. 55 On Anarcho-Syndicalism .................................. 55 The Counter-Revolution and the Destruction of the Collectives by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 56 Chapter 4: The Limitations of the Revolution 63 Introduction ............................................ 63 2 The Limitations of the Revolution by Gaston Leval ....................................... 63 Part Two: The Social Revolution 72 Chapter 5: The Economics of Revolution 74 Introduction ........................................... -

Memòria Fundació Ernest Lluch Sumari 0

’08 Memòria Fundació Ernest Lluch Sumari 0 1. Presentació 3 2. Òrgans de Govern / Seccions Territorials 6 3. Informe de Gestió 2008 11 3.1.Informe d’activitats 12 3.2.Dades Econòmiques 22 4. Memòria detallada d’activitats 2008 per àmbits territorials 31 4.1. Activitats Catalunya 32 4.2. Secció Aragonesa 66 4.4. Secció Madrilenya 76 4.3. Secció Basca 81 4.5. Secció Valenciana 84 5. Cronologia 89 6. Publicacions 95 1 Presentació Benvolgudes i benvolguts, Des de la seva constitució, el 21 de gener de 2002, els objectius de la Fundació responen, Madrid el 25 de gener de 2008 i des de llavors ha estat a Saragossa, Sant Sebastià, per una part, a la necessitat de mantenir viva la memòria, el pensament i l’obra d’Ernest Santander i Vitoria. En aquesta mateixa direcció cal destacar els esforços esmerçats en la Lluch, i per l’altra, a la voluntat de promoure activitats basant-se en la reflexió intel·lectual, la creació de l’Arxiu Ernest Lluch que s’ubicarà a la que esperem sigui la nova seu de la Fundació producció acadèmica, els compromisos cívics i les aspiracions socials, culturals i esportives aquest proper 2009, la Biblioteca Ernest Lluch de Vilassar de Mar. Un segon eix d’activitats de amb les que Ernest Lluch ens interpel·lava. la Fundació està basat en el desenvolupament dels projectes en el si dels 4 àmbits temàtics que estructuren les activitats de la Fundació. En aquests sentit, cal destacar la consolidació És per aquest motiu, que des dels seus inicis la Fundació promou, organitza i realitza, un del programa de beques i premis, la Conferència Acadèmica Ernest Lluch i els seminaris i cur- ampli ventall d’activitats relacionades amb el bagatge intel·lectual, cultural i acadèmic sos com els realitzats a la Universitat Pompeu Fabra, la Universitat de Barcelona, la Universitat d’Ernest Lluch, en els àmbits en què va excel·lir i pels quals fou reconeguda la seva person- Internacional Menéndez y Pelayo, a Santander, la Universitat del Pais Basc, o la Universitat de alitat i aportació. -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

“Behind-The-Table” Conflicts in the Failed Negotiation for a Referendum for the Independence of Catalonia

“Behind-the-Table” Conflicts in the Failed Negotiation for a Referendum for the Independence of Catalonia Oriol Valentí i Vidal*∗ Spain is facing its most profound constitutional crisis since democracy was restored in 1978. After years of escalating political conflict, the Catalan government announced it would organize an independence referendum on October 1, 2017, an outcome that the Spanish government vowed to block. This article represents, to the best of the author’s knowledge, the first scholarly examination to date from a negotiation theory perspective of the events that hindered political dialogue between both governments regarding the organization of the secession vote. It applies Robert H. Mnookin’s insights on internal conflicts to identify the apparent paradox that characterized this conflict: while it was arguably in the best interest of most Catalans and Spaniards to know the nature and extent of the political relationship that Catalonia desired with Spain, their governments were nevertheless unable to negotiate the terms and conditions of a legal, mutually agreed upon referendum to achieve this result. This article will argue that one possible explanation for this paradox lies in the “behind-the-table” *Attorney; Lecturer in Law, Barcelona School of Management (Universitat Pompeu Fabra) as of February 2018. LL.M. ‘17, Harvard Law School; B.B.A. ‘13 and LL.B. ‘11, Universitat Pompeu Fabra; Diploma in Legal Studies ‘10, University of Oxford. This article reflects my own personal views and has been written under my sole responsibility. As such, it has not been written under the instructions of any professional or academic organization in which I render my services. -

Article Journal of Catalan Intellectual History, Volume I, Issue 1, 2011 | Print ISSN 2014-1572 / Online ISSN 2014-1564 DOI 10.2436/20.3001.02.1 | Pp

article Journal of Catalan IntelleCtual HIstory, Volume I, Issue 1, 2011 | Print ISSN 2014-1572 / online ISSN 2014-1564 DoI 10.2436/20.3001.02.1 | Pp. 27-45 http://revistes.iec.cat/index.php/JoCIH Ignasi Casanovas and Frederic Clascar. Historiography and rediscovery of the thought of the 1700s and 1800s* Miquel Batllori abstract This text shows the similitudes and the differences between Ignasi Casanovas and Frederic Clascar, two of the most important representatives of the religious thought in Catalonia, in the first third of the 20th century. The article studies their philosophi- cal writings in the rich context of their global work, analysing their deficiencies and underlining the positive contribution to the Catalan culture. key words Ignasi Casanovas, Frederic Clascar, religious thought. I would like to begin with a small anecdote on the question as to whether there is such a thing as “Catalan” philosophy. Whilst teaching at Harvard, Juan Mar- ichal, publisher and scholar of the life and political works of Manuel Azaña, was asked by an American colleague what he taught there. On receiving the answer “the History1 of Latin America Thought”, the colleague replied, “Is there such * We would like to thank INEHCA and the Societat Catalana de Filosofia (Catalan Philo- sophical Society) for allowing us to public the text of this speech given by Father Miquel Batllori on 26 February 2002 as part of the course “Thought and Philosophy in Catalonia. I: 1900- 1923” at the INEHCA. The text, corrected by Miquel Batllori, has been published in the first of the volumes containing the contributions made in these courses: J. -

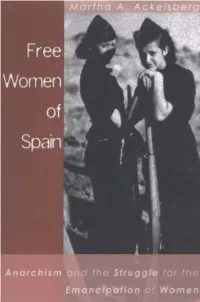

Ackelsberg L

• • I I Free Women of Spain Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women I Martha A. Ackelsberg l I f I I .. AK PRESS Oakland I West Virginia I Edinburgh • Ackelsberg. Martha A. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women Lihrary of Congress Control Numher 2003113040 ISBN 1-902593-96-0 Published hy AK Press. Reprinted hy Pcrmi"inn of the Indiana University Press Copyright 1991 and 2005 by Martha A. Ackelsherg All rights reserved Printed in Canada AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612-1163 USA (510) 208-1700 www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh. EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555-5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] The addresses above would be delighted to provide you with the latest complete AK catalog, featur ing several thousand books, pamphlets, zines, audio products, videos. and stylish apparel published and distributed bv AK Press. A1tern�tiv�l�! Uil;:1t r\llr "-""'l:-,:,i!'?� f2":' �!:::: :::::;:;.p!.::.;: ..::.:.:..-..!vo' :uh.. ,.",i. IIt;W� and updates, events and secure ordering. Cover design and layout by Nicole Pajor A las compafieras de M ujeres Libres, en solidaridad La lucha continua Puiio ell alto mujeres de Iberia Fists upraised, women of Iheria hacia horiz,ontes prePiados de luz toward horizons pregnant with light por rutas ardientes, on paths afire los pies en fa tierra feet on the ground La frente en La azul. face to the blue sky Atirmondo promesas de vida Affimling the promise of life desafiamos La tradicion we defy tradition modelemos la arcilla caliente we moLd the warm clay de un mundo que nace del doLor.