Avila Gillian M 2020 Masters.Pdf (12.22Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vibrations of Emptiness ❙

from Croatian stages: Vibrations of Emptiness ❙ A review of the performance SJENA (SHADOW) by MARIJA ©ΔEKIΔ ❙ Iva Nerina Sibila The same stream of life that runs through my veins One thing is certain, the question about the meaning and night and day runs through the world and dances approach to writing about dance comes to a complete halt in rhythmic measures. when the task at hand is writing about an exceptional per- formance. Such performances offer us numerous forays into It is the same life that shoots in joy through the dust of the world of the author, numerous interpretations and analy- the earth in numberless blades of grass and breaks into ses, as well as reasons why to write about it. I believe that tumultuous waves of leaves and flowers. Shadow, which is the impetus for this text, is one such per- formance. It is the same life that is rocked in the ocean-cradle of birth and of death, in ebb and in flow. Implosion of Opposites Travelling within the space of Shadow, we encounter a I feel my limbs are made glorious by the touch of this series of opposite notions. Art ∑ science, East ∑ West, body world of life. And my pride is from the life-throb of ages ∑ spirit, improvisation ∑ choreography, male ∑ female, young dancing in my blood this moment. ∑ old are all dualities that are continuously repeated no mat- Tagore ter which direction the analysis takes. Treated in the pre-text of Marija ©ÊekiÊ and her associ- ates these oppositions do not cancel each other out, do not I recently participated in a discussion on the various ways join together, do not enter into conflict, nor confirm each in which one can write about a dance performance. -

The Sought for Butoh Body: Tatsumi Hijikata's Cultural Rejection And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Waseda University Transcommunication Vol.3-1 Spring 2016 Graduate School of International Culture and Communication Studies Article The Sought For Butoh Body: Tatsumi Hijikata’s Cultural Rejection and Creation Julie Valentine Dind Abstract This paper studies the influence of both Japanese and Western cultures on Hijikata Tatsumi’s butoh dance in order to problematize the relevance of butoh outside of the cultural context in which it originated. While it is obvious that cultural fusion has been taking place in the most recent developments of butoh dance, this paper attempts to show that the seeds of this cultural fusion were already present in the early days of Hijikata’s work, and that butoh dance embodies his ambivalence toward the West. Moreover this paper furthers the idea of a universal language of butoh true to Hijikata’s search for a body from the “world which cannot be expressed in words”1 but only danced. The research revolves around three major subjects. First, the shaping power European underground literature and German expressionist dance had on Hijikata and how these influences remained present in all his work throughout his entire career. Secondly, it analyzes the transactions around the Japanese body and Japanese identity that take place in the work of Hijikata in order to see how Western culture might have acted as much as a resistance as an inspiration in the creation of butoh. Third, it examines the unique aspects of Hijikata’s dance, in an attempt to show that he was not only a product of his time but also aware of the shaping power of history and actively fighting against it in his quest for a body standing beyond cultural fusion or history. -

Raquel Almazan

RAQUEL ALMAZAN RAQUEL.ALMAZAN@ COLUMBIA.EDU WWW.RAQUELALMAZAN.COM SUMMARY Raquel Almazan is an actor, writer, director in professional theatre / film / television productions. Her eclectic career as artist-activist spans original multi- media solo performances, playwriting, new work development and dramaturgy. She is a practitioner of Butoh Dance and creator/teacher of social justice arts programs for youth/adults, several focusing on social justice. Her work has been featured in New York City- including Off-Broadway, throughout the United States and internationally in Greece, Italy, Slovenia, Colombia, Chile, Guatemala and Sweden; including plays within her lifelong project on writing bi-lingual plays in dedication to each Latin American country (Latin is America play cycle). EDUCATION MFA Playwriting, School of the Arts Columbia University, New York City BFA Theatre Performance/Playwriting University of Florida-New World School of With honors the Arts Conservatory, Miami, Florida AA Film Directing Miami Dade College, Miami Florida PLAYWRITING – Columbia University Playwriting through aesthetics/ Playwriting Projects: Charles Mee Play structure and analysis/Playwriting Projects: Kelly Stuart Thesis and Professional Development: David Henry Hwang and Chay Yew American Spectacle: Lynn Nottage Political Theatre/Dramaturgy: Morgan Jenness Collaboration Class- Mentored by Ken Rus Schmoll Adaptation: Anthony Weigh New World SAC Master Classes Excerpt readings and feedback on Blood Bits and Junkyard Food plays: Edward Albee Writing as a career- -

La Voz September 2005

WWW.LAVOZ.US.COM PERIÓDICO BILINGÜE ABRIL • APRILH 2011 PO BOX 3688, SANTA ROSA, CA 95402 VOLUME / VOLUMEN X, NUMBER / NÚMERO 5 ¡Nueva galería de fotos de La Voz ! www.lavoz.us.com 50% INGLÉS – 50% ESPAÑOL, un periódico comunitario producido y operado en la región. 50% IN ENGLISH! BILINGUAL New La Voz photo gallery! www.lavoz.us.com The Voice 50% ENGLISH – 50% SPANISH NEWSPAPER locally owned and operated © 2011 • La Voz • 50¢ community newspaper. BILINGUAL NEWSPAPER ¡50% EN ESPAÑOL! El Mejor Periódico Bilingüe del Norte de California NORTHERN CALIFORNIA’S FOREMOST BILINGUAL NEWSPAPER DOS IDIOMAS, DOS CULTURAS, UN ENTENDIMIENTO BalenciagaBalenciagaandSpain, and Spain, de YoungoungMuseum, Museum, SananFr Francisco TWO LANGUAGES, TWO CULTURES, BalenciagaBalenciagayEspaña, y España, MuseoMuseoDe De Young, enenS SananFr Francisco ONE UNDERSTANDING ¡VENGA A CELEBRAR EL 10mo. ANIVERSARIO DEL CENTRO PARA LA JORNADA DIARIA DE GRATON! viernes, 8 de abril, 2011 de 7pm - 11pm Sebastopol Community Cultural Center, 390 Morris St, Sebastopol, CA Compre sus boletos por Internet: brownpapertickets.com Precio de $25 - $50. Gratis-niños menores de 14. No se rechaza a persona alguna por falta de fondos. Para boletos e informacion llame al 707.829.1864 www.gratondaylabor.org COME CELEBRATE THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE GRATON DAY LABOR CENTER! Friday, April 8th, 2011 from 7pm - 11pm Spain, ca. 1922. Mantón de Manila (shawl) Silk, polychrome silk floral embroidery. The Hispanic Society of America, New York, gift of Mary Ellen Padin 2002. Foto de / Photo by Ani Weaver Sebastopol Community Cultural Center La colonización española en Filipinas inició en el siglo XVI, asimismo durante la infancia de Cristóbal Balenciaga mucha de la riqueza de la costa vasca aún se derivaba del intercambio 390 Morris Street, Sebastopol, CA 95472 con ese país. -

Female Flamenco Artists: Brave, Transgressive, Creative Women, Masters

Ángeles CRUZADO RODRÍGUEZ Universidad de Sevilla Female flamenco artists: brave, transgressive, creative women, masters... essential to understand flamenco history Summary From its birth, in the last third of nineteenth century, and during the first decades of the twentieth, flamenco has counted on great female leading figures -singers, dancers and guitar players-, who have made important contributions to that art and who, in many cases, have ended their lives completely forgotten and ruined. On the other hand, in Francoist times, when it was sought to impose the model of the woman as mother and housewife, it is worth emphasizing another range of female figures who have not developed a professional career but have assumed the important role of transmitting their rich artistic family legacy to their descendants. Besides rescuing many of these leading figures, this article highlights the main barriers and difficulties that those artists have had to face because they were women. Keywords: flamenco history, women, flamenco singers, flamenco dancers, guitar players 1. Introduction Flamenco is an art in which, from the beginning, there has been an important gender segregation. Traditionally women have been identified with dancing, which favours body exhibition, while men have been related to guitar playing and to those flamenco styles which are considered more solemn, such as seguiriya. Nevertheless, this type of attitudes are based in prejudices without a scientific base. Re-reading flamenco history from gender perspective will allow us to discover the presence of a significant number of women, many of whom have been forgotten, whose contribution has been essential to mold flamenco art as we know it now. -

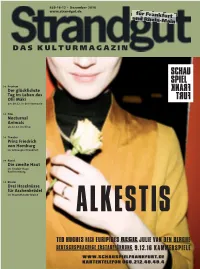

D a S K U L T U R M a G a Z

459-16-12 s Dezember 2016 www.strandgut.de für Frankfurt und Rhein-Main D A S K U L T U R M A G A Z I N >> Preview Der glücklichste Tag im Leben des Olli Mäki am 14.12. in der Harmonie >> Film Nocturnal Animals ab 22.12. im Kino >> Theater Prinz Friedrich von Homburg im Schauspiel Frankfurt >> Kunst Die zweite Haut im Sinclair-Haus Bad Homburg >> Kinder Drei Haselnüsse für Aschenbrödel im Staatstheater Mainz ALKESTIS TED HUGHES NACH EURIPIDES REGIE JULIE VAN DEN BERGHE DEUTSCHSPRACHIGE ERSTAUFFÜHRUNG 9.12.16 KAMMERSPIELE WWW.SCHAUSPIELFRANKFURT.DE KARTENTELEFON 069.212.49.49.4 INHALT Film 4 Das unbekannte Mädchen von Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne 6 Nocturnal Animals von Tom Ford 7 Paula von Christian Schwochow 8 abgedreht Sully © Warner Bros. 8 Frank Zappa – Eat That Question von Thorsten Schütte 9 Treppe 41 10 Filmstarts Preview Zwischen Wachen 5 Der glücklichste Tag im Leben des Olli Mäki und Träumen Frank Zappa © Frank Deimel »Nocturnal Animals« von Tom Ford Theater Schon in den ersten Bildern 17 Tanztheater 6 herrscht ein beunruhigender 18 Der Nussknacker im Staatstheater Darmstadt Widerspruch zwischen abstoßender 19 Late Night Hässlichkeit und perfektionistischer in der Schmiere Ästhetik: Zu sehen ist in Zeitlupe wa- 20 Hass berndes Fleisch von alten, grotesk auf den Landungsbrücken 20 vorgeführt fetten Frauenkörpern vor einem Das unbekannte Mädchen 21 Jesus und Novalis leuchtend roten Vorhang. Die Da- bei Willy Praml men sind Teil einer Ausstellung, die 22 Kafka/Heimkehr die Galeristin Susan Morrow (Amy in der Wartburg Wiesbaden 23 Prinz Friedrich von Homburg Adams) kuratiert hat. -

Spain and the Philippines at Empire's End | University of Warwick

09/25/21 HP310: Spain and the Philippines at Empire's End | University of Warwick HP310: Spain and the Philippines at View Online Empire's End (2016/17) Adam Lifshey. 2008. ‘The Literary Alterities of Philippine Nationalism in José Rizal’s “El Filibusterismo”.’ PMLA 123 (5): 1434–47. http://0-www.jstor.org.pugwash.lib.warwick.ac.uk/stable/25501945?seq=1#page_scan_tab _contents. Alda Blanco. n.d. ‘Memory-Work and Empire: Madrid’s Philippines Exhibition (1887).’ Journal of Romance Studies 5 (1): 53–63. https://contentstore.cla.co.uk/secure/link?id=f9466952-5520-e711-80c9-005056af4099. Anderson, Benedict. 16AD. ‘First Filipino.’ 16AD. http://www.lrb.co.uk/v19/n20/benedict-anderson/first-filipino. ———. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Rev. and ext. ed. London: Verso. http://encore.lib.warwick.ac.uk/iii/encore/record/C__Rb2727725. Arbues-Fandos, Natalia. 2008. ‘The Manila Shawl Route.’ 2008. https://riunet.upv.es/bitstream/handle/10251/31505/2008_03_137_142.pdf?sequence=1. Camara, Eduardo Martin de la. 1922. ‘Parnaso Filipino. Antologia de Poetas Del Archipielago Magallanico.’ 1922. https://ia802609.us.archive.org/13/items/parnasofilipino16201gut/16201-h/16201-h.htm#p 103. Castro, Juan E. de. 2011. ‘En Qué Idioma Escribe Ud.?: Spanish, Tagalog, and Identity in José Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere.’ MLN 126 (2): 303–21. https://doi.org/10.1353/mln.2011.0014. ‘Christian Doctrine, in Spanish and Tagalog (Manila, 1593; World Digital Library).’ n.d. https://www.wdl.org/en/item/82/view/1/5/. ‘Competing Colonialisms: The Portuguese, Spanish and French Presence in Asia. -

García Márquez, Gabriel ''Cien Años De Soledad''-Sp-En.P65

García’s Cien Gregory Rabassa Cien años de soledad ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE de by Gabriel García Márquez Gabriel García Márquez tr. by Gregory Rabassa bajado de Libros Tauro Avon Books, http://www.LibrosTauro.com.ar New York, USA [incontables errores de escaner sobre todo de concordancias] I. Chapter 1 Muchos años después, frente al pelotón de fusilamiento, el coronel MANY YEARS LATER as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía había de recordar aquella tarde remota en que su padre Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his lo llevó a conocer el hielo. Macondo era entonces una aldea de veinte casas father took him to discover ice. At that time Macondo was a village of de barro y cañabrava construidas a la orilla de un río de aguas diáfanas que twenty adobe houses, built on the bank of a river of clear water that ran se precipitaban por un lecho de piedras pulidas, blancas y enormes como along a bed of polished stones, which were white and enormous, like huevos prehistóricos. El mundo era tan reciente, que muchas cosas care- prehistoric eggs. The world was so recent that many things lacked names, cían de nombre, y para mencionarlas había que señalarías con el dedo. and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point. Todos los años, por el mes de marzo, una familia de gitanos Every year during the month of March a family of ragged gypsies desarrapados plantaba su carpa cerca de la aldea, y con un grande would set up their tents near the village, and with a great uproar of alboroto de pitos y timbales daban a conocer los nuevos inventos. -

Here Has Been a Substantial Re-Engagement with Ibsen Due to Social Progress in China

2019 IFTR CONFERENCE SCHEDULE DAY 1 MONDAY JULY 8 WG 1 DAY 1 MONDAY July 8 9:00-10:30 WG1 SAMUEL BECKETT WORKING GROUP ROOM 204 Chair: Trish McTighe, University of Birmingham 9:00-10:00 General discussion 10:00-11:00 Yoshiko Takebe, Shujitsu University Translating Beckett in Japanese Urbanism and Landscape This paper aims to analyze how Beckett’s drama especially Happy Days is translated within the context of Japanese urbanism and landscape. According to Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, “shifts are seen as required, indispensable changes at specific semiotic levels, with regard to specific aspects of the source text” (Baker 270) and “changes at a certain semiotic level with respect to a certain aspect of the source text benefit the invariance at other levels and with respect to other aspects” (ibid.). This paper challenges to disclose the concept of urbanism and ruralism that lies in Beckett‘s original text through the lens of site-specific art demonstrated in contemporary Japan. Translating Samuel Beckett’s drama in a different environment and landscape hinges on the effectiveness of the relationship between the movable and the unmovable. The shift from Act I into Act II in Beckett’s Happy Days gives shape to the heroine’s urbanism and ruralism. In other words, Winnie, who is accustomed to being surrounded by urban materialism in Act I, is embedded up to her neck and overpowered by the rural area in Act II. This symbolical shift experienced by Winnie in the play is aesthetically translated both at an urban theatre and at a cave-like theatre in Japan. -

Encounters with Nelida Tirado, José Moreno and Calvin Hazen

Studio BFPL: Encounters with Nelida Tirado, José Moreno and Calvin Hazen Nelida Tirado, dance José Moreno, voice Calvin Hazen, guitar LAND "Solea" abbreviated from the word "Soledad' often referred to as the Mother of the flamenco forms, means loneliness. The feeling and content of the music/dance is generally serious in nature, often with a sententious tone conveying a feeling of intimate pain and despair. SEA "Alegria" meaning joy, is of the family of vibrant flamenco forms of the rich port and naval station of Cadiz, Spain. Situated on a slice of land surrounded by sea, it boasts some of Spain's most beautiful architecture, beaches and sunny climate. The feel of the piece reflects the lively life there often referencing sailors and many seas. Accompanied by a mantón de manila, the manila shawl is very popular in Andalucia for festive occasions and also used as an accessory in the dance. The women use shawls to enhance and add drama to the performance twirling it around her body and air. AIR "Cantiñas" originating in the area of Cadiz in Andalucia, is festive reflecting the feeling of Cadiz where cantiñear is synonym of playing and improvising. Elements inherent of the spirit of cantiñas. About Nelida Tirado Nelida Tirado began her formal training at Ballet Hispanico of New York at the age of six. Barely out of her teens, she was invited to tour the U.S. with Jose Molina Bailes Españoles, a soloist in Carlota Santana’s Flamenco Vivo, soloist and dance captain in Compañía Maria Pages and in Compania Antonio El Pipa. -

Colombian Artists in Paris, 1865-1905

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2010 Colombian Artists in Paris, 1865-1905 Maya Jiménez The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2151 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] COLOMBIAN ARTISTS IN PARIS, 1865-1905 by MAYA A. JIMÉNEZ A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2010 © 2010 MAYA A. JIMÉNEZ All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Professor Katherine Manthorne____ _______________ _____________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor Kevin Murphy__________ ______________ _____________________________ Date Executive Officer _______Professor Judy Sund________ ______Professor Edward J. Sullivan_____ ______Professor Emerita Sally Webster_______ Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Colombian Artists in Paris, 1865-1905 by Maya A. Jiménez Adviser: Professor Katherine Manthorne This dissertation brings together a group of artists not previously studied collectively, within the broader context of both Colombian and Latin American artists in Paris. Taking into account their conditions of travel, as well as the precarious political and economic situation of Colombia at the turn of the twentieth century, this investigation exposes the ways in which government, politics and religion influenced the stylistic and thematic choices made by these artists abroad. -

Chinese Objects in the Museo Historico Nacional Collection

FROM CHINA TO CHILE: CHINESE OBJECTS IN THE MUSEO HISTORICO NACIONAL COLLECTION ISABEL ALVARADO PERALES Chief, Department of Exhibitions and Conservation, National Historical Museum, Santiago, Chile Abstract: The textile and costume collection of the National Historical Museum in Santiago, Chile, contains many objects from China. Among these artifacts are silk Manila shawls, embroidered with flowers and fringed on all sides. Contents: Museo Histórico Nacional, National Historical Museum, Santiago, Chile; Chinese Artifacts; Manila Shawls; Embroidery Introduction The textile and costume collection of the National Historical Museum contains a variety of clothing and textiles artifacts. Most of these objects were used in Chile; some of them were made in the country; and others were brought from Europe. However, there are a small number of pieces that were included in donations from collectors who traveled around the world in search of objects and then donated their personal collections when the museum was founded in 1911. Artifacts from China including Manila Shawls Examples of pieces coming from China are a pair lotus shoes decorated with embroidered flowers with colorful silk threads (Fig. 1), a pair of boots with embroidered decorative patterns (Fig. 2), and two brisé fans from China, one made of ivory (Fig. 3) and the other made in dark tortoiseshell (Fig. 4), both from the nineteenth century. Also coming from China, the museum has in its collection an important number of Manila shawls, especially black ones. This kind of shawl is a square piece of silk cloth fully-embroidered. To use it as a garment, the shawl was folded in half like a triangle and worn over the shoulders.