Practices of Polish Butō Dancers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Golem Allegories

IRIE International Review of Information Ethics Vol. 26 (12/2017) Ivan Capeller: The Golem Allegories This is the first piece of a three-part article about the allegorical aspects of the legend of the Golem and its epistemological, political and ethical implications in our Internet plugged-in connected times. There are three sets of Golem allegories that may refer to questions relating either to language and knowledge, work and technique, or life and existence. The Golem allegories will be read through three major narratives that are also clearly or potentially allegorical: Walter Benjamin’s allegory of the chess player at the very beginning of his theses On the Concept of History, William Shakespeare’s last play The Tempest and James Cameron’s movie The Terminator. Each one of these narratives is going to be considered as a key allegory for a determinate aspect of the Golem, following a three-movement reading of the Golem legend that structures this very text as its logical outcome. Agenda: The Golem and the Chess Player: Language, Knowledge and Thought........................................ 79 Between Myth and Allegory ................................................................................................................. 79 Between the Puppet and the Dwarf ..................................................................................................... 82 Between Bio-Semiotics and Cyber-Semiotics ........................................................................................ 85 Author: Prof. Dr. Ivan Capeller: Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação (PPGCI) e Escola de Comunicação (ECO) da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro/RJ, [email protected] Relevant publications: - A Pátina do Filme: da reprodução cinemática do tempo à representação cinematográfica da história. Revista Matrizes (USP. Impresso) , v. V, p. 213-229, 2009 - Kubrick com Foucault, o desvio do panoptismo. -

The Body in Question: the Income Tax and Human Body Materials

ZELENAK_FORMATTED_PREPROOF_PERMA (DO NOT DELETE) 3/14/2017 2:18 PM THE BODY IN QUESTION: THE INCOME TAX AND HUMAN BODY MATERIALS ∗ LAWRENCE ZELENAK I INTRODUCTION The federal income tax treatment of transactions in human body materials— such as eggs, sperm, blood, milk, hair, and kidneys—is a mess. Nothing is firmly settled. Consider, for example, the recent first-impression case of Perez v. Commissioner,1 in which the Tax Court concluded that a paid “donor” of ova had received fully taxable compensation-for-services income (rejecting the taxpayer’s claim that the payments qualified under the statutory exclusion from gross income of “damages . on account of personal physical injuries”2). By contrast, academic commentators writing before Perez had thought it fairly obvious that a paid egg donor was the seller of an asset,3 thus giving rise to at least the possibility of taxation at the favorable rates applicable to long-term capital gain. Similar confusion reigns in the case of taxpayers who donate their blood to charity. There is support both for the proposition that a blood donor performs a service for the charity4 (and so is subject to the rule that contributions of services are not deductible5), and also for the proposition that a blood donation is a contribution of property (the value of which would be deductible but for the happenstance that blood cells do not live long enough to satisfy the holding period for long-term capital gain).6 Although the same no-deduction result is Copyright © 2017 by Lawrence Zelenak. This article is also available online at http://lcp.law.duke.edu/. -

Vibrations of Emptiness ❙

from Croatian stages: Vibrations of Emptiness ❙ A review of the performance SJENA (SHADOW) by MARIJA ©ΔEKIΔ ❙ Iva Nerina Sibila The same stream of life that runs through my veins One thing is certain, the question about the meaning and night and day runs through the world and dances approach to writing about dance comes to a complete halt in rhythmic measures. when the task at hand is writing about an exceptional per- formance. Such performances offer us numerous forays into It is the same life that shoots in joy through the dust of the world of the author, numerous interpretations and analy- the earth in numberless blades of grass and breaks into ses, as well as reasons why to write about it. I believe that tumultuous waves of leaves and flowers. Shadow, which is the impetus for this text, is one such per- formance. It is the same life that is rocked in the ocean-cradle of birth and of death, in ebb and in flow. Implosion of Opposites Travelling within the space of Shadow, we encounter a I feel my limbs are made glorious by the touch of this series of opposite notions. Art ∑ science, East ∑ West, body world of life. And my pride is from the life-throb of ages ∑ spirit, improvisation ∑ choreography, male ∑ female, young dancing in my blood this moment. ∑ old are all dualities that are continuously repeated no mat- Tagore ter which direction the analysis takes. Treated in the pre-text of Marija ©ÊekiÊ and her associ- ates these oppositions do not cancel each other out, do not I recently participated in a discussion on the various ways join together, do not enter into conflict, nor confirm each in which one can write about a dance performance. -

The Sought for Butoh Body: Tatsumi Hijikata's Cultural Rejection And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Waseda University Transcommunication Vol.3-1 Spring 2016 Graduate School of International Culture and Communication Studies Article The Sought For Butoh Body: Tatsumi Hijikata’s Cultural Rejection and Creation Julie Valentine Dind Abstract This paper studies the influence of both Japanese and Western cultures on Hijikata Tatsumi’s butoh dance in order to problematize the relevance of butoh outside of the cultural context in which it originated. While it is obvious that cultural fusion has been taking place in the most recent developments of butoh dance, this paper attempts to show that the seeds of this cultural fusion were already present in the early days of Hijikata’s work, and that butoh dance embodies his ambivalence toward the West. Moreover this paper furthers the idea of a universal language of butoh true to Hijikata’s search for a body from the “world which cannot be expressed in words”1 but only danced. The research revolves around three major subjects. First, the shaping power European underground literature and German expressionist dance had on Hijikata and how these influences remained present in all his work throughout his entire career. Secondly, it analyzes the transactions around the Japanese body and Japanese identity that take place in the work of Hijikata in order to see how Western culture might have acted as much as a resistance as an inspiration in the creation of butoh. Third, it examines the unique aspects of Hijikata’s dance, in an attempt to show that he was not only a product of his time but also aware of the shaping power of history and actively fighting against it in his quest for a body standing beyond cultural fusion or history. -

By Michio Arimitsu from Voodoo to Butoh

From Voodoo to Butoh: Katherine By Michio Arimitsu Dunham, Hijikata Tatsumi, and Trajal Harrell’s Transcultural Refashioning of “Blackness” I said black is . an’ black ain’t . Black will git you . put butoh aesthetics and techniques in dialogue with an’ black won’t. [. .] Black will make you . or black those of voguing, has given us a tantalizing glimpse will unmake you. of what’s to come.5 Rather than directly engaging – Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952) with Harrell’s ongoing refashioning of butoh, I want to underscore the cultural significance of his endeavor by I remember Hijikata’s body—a northern body, the skin situating it in the history of Afro-Asian performative very white, the hair standing out very black against it. exchange across the Pacific. More specifically, however, – Donald Richie, “On Tatsumi Hijikata” (1987) I want to shed a new light on an encounter between Hijikata and Katherine Dunham (1909–2006), the pioneering African American modern dancer, at a Introduction: What Would Have Happened if Hijikata decisive moment before Hijikata’s “dance of darkness/ Tatsumi Had Not Seen Katherine Dunham in 1957? blackness” was born. As I argue, Dunham’s voodoo- Like a skilled designer who duly respects the traditions, inspired performance, along with torrential imports of but is never afraid of pushing the boundaries of the other African American/Afro-Caribbean images and fashion world, Trajal Harrell fascinates and provokes cultural forms into post-WWII Japan, had a much more his audience by tailoring seemingly disparate materials crucial role in the early aesthetics of butoh than has from near and far to his own eclectic choreography. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Raquel Almazan

RAQUEL ALMAZAN RAQUEL.ALMAZAN@ COLUMBIA.EDU WWW.RAQUELALMAZAN.COM SUMMARY Raquel Almazan is an actor, writer, director in professional theatre / film / television productions. Her eclectic career as artist-activist spans original multi- media solo performances, playwriting, new work development and dramaturgy. She is a practitioner of Butoh Dance and creator/teacher of social justice arts programs for youth/adults, several focusing on social justice. Her work has been featured in New York City- including Off-Broadway, throughout the United States and internationally in Greece, Italy, Slovenia, Colombia, Chile, Guatemala and Sweden; including plays within her lifelong project on writing bi-lingual plays in dedication to each Latin American country (Latin is America play cycle). EDUCATION MFA Playwriting, School of the Arts Columbia University, New York City BFA Theatre Performance/Playwriting University of Florida-New World School of With honors the Arts Conservatory, Miami, Florida AA Film Directing Miami Dade College, Miami Florida PLAYWRITING – Columbia University Playwriting through aesthetics/ Playwriting Projects: Charles Mee Play structure and analysis/Playwriting Projects: Kelly Stuart Thesis and Professional Development: David Henry Hwang and Chay Yew American Spectacle: Lynn Nottage Political Theatre/Dramaturgy: Morgan Jenness Collaboration Class- Mentored by Ken Rus Schmoll Adaptation: Anthony Weigh New World SAC Master Classes Excerpt readings and feedback on Blood Bits and Junkyard Food plays: Edward Albee Writing as a career- -

Axon February 2019 Release Notes

Axon February 2019 Release Notes Document Revision: A Evidence.com Version 2019.2 Axon February 2019 Release Notes Apple, iOS, and Safari are trademarks of Apple, Inc. registered in the US and other countries. Firefox is a trademark of The Mozilla Foundation registered in the US and other countries. Google, Google Play, Android, and Chrome are trademarks of Google, Inc. Microsoft, Windows, Internet Explorer, and Excel are trademarks of Microsoft Corporation registered in the US and other countries. Javascript is a trademark of Oracle America, Inc. registered in the US and other countries. , Axon, Axon Body, Axon Body 2, Axon Capture, Axon Citizen, Axon Dock, Axon Fleet, Axon Fleet 2, Axon Flex, Axon Flex 2, Axon Interview, Axon View, Axon View XL, Evidence.com (Axon Evidence), Evidence.com Lite, Evidence Sync, and TASER are trademarks of Axon Enterprise, Inc., some of which are registered in the US and other countries. For more information, visit www.axon.com/legal. All rights reserved. ©2019 Axon Enterprise, Inc. Axon Enterprise, Inc. Page 2 of 24 Axon February 2019 Release Notes Table of Contents Overview ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Important Information for Evidence Sync users with Axon Body 2...................................................... 5 Axon Evidence.com February Release Updates ...................................................................................... 5 Evidence Groups ....................................................................................................................................... -

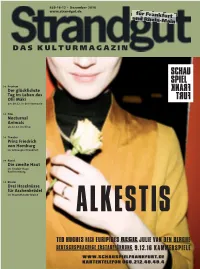

D a S K U L T U R M a G a Z

459-16-12 s Dezember 2016 www.strandgut.de für Frankfurt und Rhein-Main D A S K U L T U R M A G A Z I N >> Preview Der glücklichste Tag im Leben des Olli Mäki am 14.12. in der Harmonie >> Film Nocturnal Animals ab 22.12. im Kino >> Theater Prinz Friedrich von Homburg im Schauspiel Frankfurt >> Kunst Die zweite Haut im Sinclair-Haus Bad Homburg >> Kinder Drei Haselnüsse für Aschenbrödel im Staatstheater Mainz ALKESTIS TED HUGHES NACH EURIPIDES REGIE JULIE VAN DEN BERGHE DEUTSCHSPRACHIGE ERSTAUFFÜHRUNG 9.12.16 KAMMERSPIELE WWW.SCHAUSPIELFRANKFURT.DE KARTENTELEFON 069.212.49.49.4 INHALT Film 4 Das unbekannte Mädchen von Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne 6 Nocturnal Animals von Tom Ford 7 Paula von Christian Schwochow 8 abgedreht Sully © Warner Bros. 8 Frank Zappa – Eat That Question von Thorsten Schütte 9 Treppe 41 10 Filmstarts Preview Zwischen Wachen 5 Der glücklichste Tag im Leben des Olli Mäki und Träumen Frank Zappa © Frank Deimel »Nocturnal Animals« von Tom Ford Theater Schon in den ersten Bildern 17 Tanztheater 6 herrscht ein beunruhigender 18 Der Nussknacker im Staatstheater Darmstadt Widerspruch zwischen abstoßender 19 Late Night Hässlichkeit und perfektionistischer in der Schmiere Ästhetik: Zu sehen ist in Zeitlupe wa- 20 Hass berndes Fleisch von alten, grotesk auf den Landungsbrücken 20 vorgeführt fetten Frauenkörpern vor einem Das unbekannte Mädchen 21 Jesus und Novalis leuchtend roten Vorhang. Die Da- bei Willy Praml men sind Teil einer Ausstellung, die 22 Kafka/Heimkehr die Galeristin Susan Morrow (Amy in der Wartburg Wiesbaden 23 Prinz Friedrich von Homburg Adams) kuratiert hat. -

So Who Taught Master Funakoshi?

OSS!! Official publication of KARATENOMICHI MALAYSIA VOLUME 1 EDITION 1 SO WHO TAUGHT MASTER FUNAKOSHI? Tomo ni Karate no michi ayumu In his bibliography, Gichin Funakoshi wrote that he had two main teachers, Masters Azato and Itosu, though he s ometimes trained under IN THIS ISSUE Matsumura, Kiyuna, Kanryo Higaonna, and SO WHO TAUGHT MASTER Niigaki. Who were these two Masters and FUNAKOSHI? SHU-HA-RI how did they influence him? ISAKA SENSEI FUNDAMENTALS (SIT DOWN LESSON) : SEIZA Yasutsune “Ankoh” Azato (1827–1906) was born into a family of hereditary THE SHOTO CENTRE MON chiefs of Azato, a village between the towns of Shuri and Naha. Both he and his good friend Yasutsune Itosu learned karate from Sokon FUNAKOSHI O’SENSEI MEMORIAL “Bushi” Matsumura, bodyguard to three Okinawan kings. He had legendary GASSHUKU 2009 martial skills employing much intelligence and strategy over strength and 2009 PLANNER ferocity. Funakoshi states that though lightly built when he began training, after a few years Azato as well as Itosu had developed their physiques “to admirable and magnificent degrees.” ANGRY WHITE PYJAMAS FIGHT SCIENCE Azato was skilled in karate, horsemanship, archery, Jigen Ryu ken-jutsu, MEMBER’S CONTRIBUTIONS Chinese literature and politics. SPOTLIGHT Continued on page 2 READABLES DVD FIGHT GEAR TEAM KIT FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK Welcome to the inaugural issue of OSS!! To some of the members who have been with us for quite sometime knows how long this newsletter have been in planning. Please don’t forget to send me your feedback so that I can make this newsletter a better resource for all of us. -

United States District Court Eastern District Of

Case 2:13-cv-05463-KDE-SS Document 1 Filed 08/16/13 Page 1 of 118 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA PAUL BATISTE D/B/A * CIVIL ACTION NO. ARTANG PUBLISHING LLC * * SECTION: “ ” Plaintiff, * * JUDGE VERSUS * * MAGISTRATE FAHEEM RASHEED NAJM, P/K/A T-PAIN, KHALED * BIN ABDUL KHALED, P/K/A DJ KHALED, WILLIAM * ROBERTS II, P/K/A RICK ROSS, ANTOINE * MCCOLISTER P/K/A ACE HOOD, 4 BLUNTS LIT AT * ONCE PUBLISHING, ATLANTIC RECORDING * CORPORATION, BYEFALL MUSIC LLC, BYEFALL * PRODUCTIONS, INC., CAPITOL RECORDS LLC, * CASH MONEY RECORDS, INC., EMI APRIL MUSIC, * INC., EMI BLACKWOOD MUSIC, INC., * FIRST-N-GOLD PUBLISHING, INC., FUELED BY * RAMEN, LLC, NAPPY BOY, LLC, NAPPY BOY * ENTERPRISES, LLC, NAPPY BOY PRODUCTIONS, * LLC, NAPPY BOY PUBLISHING, LLC, NASTY BEAT * MAKERS PRODUCTIONS, INC., PHASE ONE * NETWORK, INC., PITBULL’S LEGACY * PUBLISHING, RCA RECORDS, RCA/JIVE LABEL * GROUP, SONGS OF UNIVERSAL, INC., SONY * MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT DIGITAL LLC, * SONY/ATV MUSIC PUBLISHING, LLC, SONY/ATV * SONGS, LLC, SONY/ATV TUNES, LLC, THE ISLAND * DEF JAM MUSIC GROUP, TRAC-N-FIELD * ENTERTAINMENT, LLC, UMG RECORDINGS, INC., * UNIVERSAL MUSIC – MGB SONGS, UNIVERSAL * MUSIC – Z TUNES LLC, UNIVERSAL MUSIC * CORPORATION, UNIVERSAL MUSIC PUBLISHING, * INC., UNIVERSAL-POLYGRAM INTERNATIONAL * PUBLISHING, INC., WARNER-TAMERLANE * PUBLISHING CORP., WB MUSIC CORP., and * ZOMBA RECORDING LLC * * Defendants. * ****************************************************************************** Case 2:13-cv-05463-KDE-SS Document 1 Filed 08/16/13 Page 2 of 118 COMPLAINT Plaintiff Paul Batiste, doing business as Artang Publishing, LLC, by and through his attorneys Koeppel Traylor LLC, alleges and complains as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. This is an action for copyright infringement. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Liao, P. (2006). An Inquiry into the Creative Process of Butoh: With Reference to the Implications of Eastern and Western Significances. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/11883/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] An Inquiry into the Creative Process of Butoh: With Reference to the Implications of Eastern and Western Significances PhD Thesis Pao-Yi Liao Jan 2006 Laban City University London, U. K. Table of Contents Page II Table of Contents Acknowledgement IV Declaration IV Abstract V Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1 1.1 The Nature of the Research Inquiry --- ------------------------- -------- 2