Recovering the Body and Expanding the Boundaries of Self in Japanese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sought for Butoh Body: Tatsumi Hijikata's Cultural Rejection And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Waseda University Transcommunication Vol.3-1 Spring 2016 Graduate School of International Culture and Communication Studies Article The Sought For Butoh Body: Tatsumi Hijikata’s Cultural Rejection and Creation Julie Valentine Dind Abstract This paper studies the influence of both Japanese and Western cultures on Hijikata Tatsumi’s butoh dance in order to problematize the relevance of butoh outside of the cultural context in which it originated. While it is obvious that cultural fusion has been taking place in the most recent developments of butoh dance, this paper attempts to show that the seeds of this cultural fusion were already present in the early days of Hijikata’s work, and that butoh dance embodies his ambivalence toward the West. Moreover this paper furthers the idea of a universal language of butoh true to Hijikata’s search for a body from the “world which cannot be expressed in words”1 but only danced. The research revolves around three major subjects. First, the shaping power European underground literature and German expressionist dance had on Hijikata and how these influences remained present in all his work throughout his entire career. Secondly, it analyzes the transactions around the Japanese body and Japanese identity that take place in the work of Hijikata in order to see how Western culture might have acted as much as a resistance as an inspiration in the creation of butoh. Third, it examines the unique aspects of Hijikata’s dance, in an attempt to show that he was not only a product of his time but also aware of the shaping power of history and actively fighting against it in his quest for a body standing beyond cultural fusion or history. -

By Michio Arimitsu from Voodoo to Butoh

From Voodoo to Butoh: Katherine By Michio Arimitsu Dunham, Hijikata Tatsumi, and Trajal Harrell’s Transcultural Refashioning of “Blackness” I said black is . an’ black ain’t . Black will git you . put butoh aesthetics and techniques in dialogue with an’ black won’t. [. .] Black will make you . or black those of voguing, has given us a tantalizing glimpse will unmake you. of what’s to come.5 Rather than directly engaging – Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952) with Harrell’s ongoing refashioning of butoh, I want to underscore the cultural significance of his endeavor by I remember Hijikata’s body—a northern body, the skin situating it in the history of Afro-Asian performative very white, the hair standing out very black against it. exchange across the Pacific. More specifically, however, – Donald Richie, “On Tatsumi Hijikata” (1987) I want to shed a new light on an encounter between Hijikata and Katherine Dunham (1909–2006), the pioneering African American modern dancer, at a Introduction: What Would Have Happened if Hijikata decisive moment before Hijikata’s “dance of darkness/ Tatsumi Had Not Seen Katherine Dunham in 1957? blackness” was born. As I argue, Dunham’s voodoo- Like a skilled designer who duly respects the traditions, inspired performance, along with torrential imports of but is never afraid of pushing the boundaries of the other African American/Afro-Caribbean images and fashion world, Trajal Harrell fascinates and provokes cultural forms into post-WWII Japan, had a much more his audience by tailoring seemingly disparate materials crucial role in the early aesthetics of butoh than has from near and far to his own eclectic choreography. -

The Originating Impulses of Ankoku Butoh: Towards an Understanding of the Trans-Cultural Embodiment of Tatsumi Hijikata's Dance of Darkness

The originating impulses of Ankoku Butoh: Towards an understanding of the trans-cultural embodiment of Tatsumi Hijikata's dance of darkness A thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS of RHODES UNIVERSITY by Orlando Vincent Truter December 2007 1 ;, Contents Page Introduction 3 Chapter 1: Climates and concurrences 13 Chapter 2: The origin of Ankoku Butoh 23 Chapter 3: Trans-cultural embodiment of the Ankoku Butoh body 77 2 l\1akc )- Ol.ll- d""ll nures f'iEVEI~ unoc"Jille 01' ,\-,rue ill a ;ionk Introduction Ankoku Butoh is a performing art devised in Japan in the wake of the Second World War by the dancer and choreographer Tatsumi Hijikata (born Akita, 1928; died Tokyo, 1986). A highly aesthetic and subversive performing art, Butoh often evokes "images of decay, of fear and desperation, images of eroticism, ecstasy and stillness."1 Typically performed with a white layer of paint covering the entire body of the dancer, Butoh is visually characterized by continual transformations between postures, distorted physical and facial expressions, and an emphasis on condensed and visually slow movements. Some of the general characteristics of Butoh performance include "a particular openness to working with the subtle energy in the body; the malleability of time; the power of the grotesque.,,2 While Ankoku Butoh flourished in Japan during the dynamic decades of the 1960s and 1970s, Hijikata's influence has spread with travelling or migrant Japanese performers and teachers, companies and individuals who practise Butoh, or who have been influenced by Ankoku Butoh, or who appropriate elements of its aesthetic for other practices, both within and outside of the performing arts. -

Tatsumi Hijikata and Eikoh Hosoe: Collaborations with Tatsumi Hijikata

Nonaka-Hill is pleased to announce two exhibitions; Tatsumi Hijikata and Eikoh Hosoe: Collaborations with Tatsumi Hijikata These exhibitions are on view from October 12 - November 30, 2019, with an opening reception on Saturday, October 12th, 5-8pm. Tatsumi Hijikata Tatsumi Hijikata was the founder of Ankoku Butoh (literally meaning, dance of darkness), widely known and practiced today, some 60 years later, as Butoh. Hijikata arrived to Tokyo from the Northern rural Tohoku region in 1952 and worked blue-collar jobs to support his dance pursuits. As his rural accent set him apart from Tokyo's urbanites, Hijikata filled his time reading French writers, such as Jean Genet, Antonin Artaud and Georges Bataille. Aesthetically, he looked towards artists such as Egon Schiele, Hans Bellmer and Willem De Kooning. Hijikata’s provocative performances stemmed from this exploration of eros, debauchery, disease and death, evoking the rarely seen dark half of the human psyche. With awareness of German Expressionist dance and technical capabilities in Modern dance genres including jazz, flamenco, classical ballet and pantomime, Hijikata felt the imperative to develop a new dance form, and with the underlying notion of the anti-establishment, Hijikata's Butoh stands as a form of anti-dance. The exhibition's organizer, Takashi Morishita has written "Hijikata's Butoh… is body art whose expression is a "convulsion of existence"'. As an artist working in performance with relationship to Happenings, a popular in his times, Tatsumi Hijikata became a central figure -

Butoh: on the Edge of Crisis?*

BUTOH: ON THE EDGE OF CRISIS?* A Critical Analysis of the Japanese Avant-garde Project in a Postmodern Perspective MA thesis Tara Ishizuka Hassel December 2005 Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, Faculty of Humanities, University of Oslo * Hijikata often used the word crisis in a wish to express a crisis in contemporary Japanese society. The title also refers to the renowned documentary titled “Body on the edge of crisis” by Michael Blackwell productions Foreword ___________________________________________________________ 2 1 Introduction _______________________________________________________ 3 1.1 Schools of Butoh_________________________________________________ 3 1.2 Theoretical approach _____________________________________________ 5 2 The History of Butoh _______________________________________________ 9 2.1 Post-war Japan__________________________________________________ 9 2.2 Butoh’s ideological and philosophical background_____________________ 12 2.3 Ankoku Butoh _________________________________________________ 15 2.4 Influences on Butoh_____________________________________________ 18 2.5 The Butoh-fu __________________________________________________ 22 3 Method of analyzing Butoh - Phenomenology_______________________ 30 3.1 What is Phenomenology? ________________________________________ 30 3.2 The materialisation of the body and the traditional Eastern body concept ___ 32 3.3 The abandoned body and its shadows 42 3.4 Closing comment with regard on Butoh _____________________________ 46 4 Theory ___________________________________________________________ -

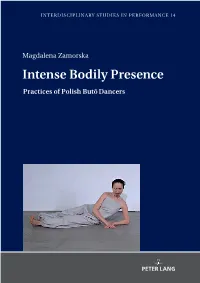

Practices of Polish Butō Dancers

Interdisciplinary Studies in Performance 14 14 Interdisciplinary Studies in Performance 14 Magdalena Zamorska Magdalena Zamorska Intense Bodily Presence The author explores the practices of Polish buto¯ dancers. Underlining the Magdalena Zamorska Magdalena transcultural potential of the genre, she discusses in particular their individual body-mind practices and so-called buto¯ techniques in order to produce a Intense Bodily Presence generalised account of buto¯ training. Her argument is underpinned by complex field research which she carried out as an expert observer and a workshop Practices of Polish Buto¯ Dancers participant. Drawing on a transdisciplinary approach, which combines insights and findings from the fields of cultural and performance studies, cultural anthropology and cognitive sciences, the book depicts the sequence of three phases which make up the processual structure of buto¯ training: intro, following and embodiment. The Author Magdalena Zamorska is a Ph.D. graduate in Humanities (2012) and an assistant professor at the Institute of Cultural Studies at the University of Wroclaw (Poland). Her research interests include movement, social choreography, issues of perception and reception in choreographic performances. She also explores the intersections of humanities and science. Intense Bodily Presence. Practices of Polish Buto¯ Dancers BodilyIntense Presence. Practices Buto¯ Polish of ISPE-14 276512_Zamorska_TL_151-214 A5HC Fusion.indd 1 08.10.18 15:10 Interdisciplinary Studies in Performance 14 14 Interdisciplinary Studies in Performance 14 Magdalena Zamorska Magdalena Zamorska Intense Bodily Presence The author explores the practices of Polish buto¯ dancers. Underlining the Magdalena Zamorska Magdalena transcultural potential of the genre, she discusses in particular their individual body-mind practices and so-called buto¯ techniques in order to produce a Intense Bodily Presence generalised account of buto¯ training. -

Exploring Japanese Avant-Garde Art Through Butoh Dance

Week1 Exploring Japanese Avant-garde Art Through Butoh Dance Handout English Version Week 1 Towards butoh: Experimentation Week 2 Dancing butoh: Embodiment Week 3 Behind butoh: Creation Week 4 Expanding butoh: Globalisation © Keio University 2019/1/6 Butoh_Week1 - Google ドキュメント Week1 Towards butoh: Experimentation WEEK 1: TOWARDS BUTOH: EXPERIMENTATION Activity 1: Introduction of the course First of all, let's watch butoh. 1.1 WELCOME TO THE WORLD OF JAPANESE AVANT-GARDE ART VIDEO (01:38) 1.2 FIRST OF ALL, LET'S SEE BUTOH ARTICLE 1.3 WHAT IS BUTOH? ARTICLE 1.4 THE BACKGROUND OF BUTOH ARTICLE Activity 2: Post-war Tokyo and the birth of Butoh Let's take a closer look at Tatsumi Hijikata himself who created butoh, as well as the social background of 1950's in Japan. 1.5 POST-WAR RECONSTRUCTION AND HIGH ECONOMIC GROWTH VIDEO (00:58) 1.6 POST-WAR JAPANESE ART ARTICLE 1.7 POST-WAR JAPANESE DANCE ARTICLE 1.8 BEFORE BUTOH VIDEO (02:43) 1.9 THE BIRTH OF BUTOH VIDEO (04:12) 1.10 THE ESTABLISHMENT OF BUTOH ARTICLE 1.11 THE WAR AND THE ART DISCUSSION Activity 3: From "happening dance" to butoh See how Japanese art absorbed, refigured and influenced Western art in the 20th century through Tatsumi Hijikata's butoh dance. 1.12 "NAVEL AND A-BOMB" ARTICLE 1.13 THE AVANT-GARDE AND EXPERIMENTS IN PHYSICAL EXPRESSION ARTICLE 1.14 AVANT-GARDE ART AND ANTI-ART ARTICLE 1.15 THE HAPPENING DANCE ARTICLE Exploring Japanese Avant-garde Art Through Butoh Dance KEIO UNIVERSITY © Keio University https://docs.google.com/document/d/1XGlM_hiVykuLtxRGv_HnU9MafeIMpLihQV0zHzSr_d0/edit# 1/56 2019/1/6 Butoh_Week1 - Google ドキュメント Week1 Towards butoh: Experimentation 1.16 THE FORMATION OF ANKOKU BUTOH VIDEO (02:25) Activity 4: Rebellion of the Body Let's learn through the work of Tatsumi Hijikata and the impact of butoh as an activity in the society. -

Hijikata Tatsumi’S from Being Jealous of a Dog’S Vein

i Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Philosophische Fakultät III Institut für Japanologie Hijikata Tatsumi’s From Being Jealous of a Dog’s Vein Magisterarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Magister Artium (M.A.) im Fach Japanologie Vorgelegt von Elena Polzer Geboren am 20. Mai 1978 in Friedrichshafen Wissenschaftlicher Betreuer Professor Dr. Klaus Kracht Berlin, 25. August 2004 ii EIGENSTÄNDIGKEITSERKLÄRUNG Ich versichere hiermit, dass ich die vorliegende Magisterarbeit selbstständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Hilfsmittel benutzt habe. Die Stellen, die anderen Werken dem Wortlaut oder dem Sinn nach entnommen wurden, habe ich in jedem einzelnen Fall durch die Angabe der Quelle, auch der benutzten Sekundärliteratur, als Entlehnung kenntlich gemacht. Berlin, 25.8.2004 Elena Polzer ii iii Deutsche Zusammenfassung Diese Arbeit besteht aus zwei Teilen. Der erste Teil der Arbeit ist eine kurze Zusammenfassung vom Leben und Werk Hijikata Tatsumis. Hijikata Tatsumi, der gemeinhin als der wichtigste Begründer des Butoh gilt, wurde 1928 als Sohn eines Bauern und Nudelladenbesitzers in der Präfektur Akita, in der Tôhoku Gegend, geboren. Mit 19 Jahren zog er zum ersten Mal in die Großstadt nach Tokyo. 1959 zeigte Hijikata zusammen mit Ohno Kazuos Sohn, Ohno Yoshito, auf dem sechsten Tanzfestival des Vereins zur Pflege des modernen Tanzes, das kurze Stück Kinjiki [Verbotene Farben]. Das düstere Stück wurde zu einem Riesenskandal. Von 1965 bis 1968 entstand der Fotoband Kamaitachi [Sichel Wiesel] in Zusammenarbeit mit Hosoe Eikoh. 1968 war auch das Jahr seines sicherlich bekanntesten Stückes: Hijikata Tatsumi to nihonjin - nikutai no hanran [Hijikata Tatsumi und die Japaner – die Rebellion des Körpers]. Wenig später hörte Hijikata auf selber zu tanzen, und widmete sich nur noch der Choreographie. -

Duality, Symbolism, and Time: a Convergent Practice in Butoh and Surrealist Expression

DUALITY, SYMBOLISM, AND TIME: A CONVERGENT PRACTICE IN BUTOH AND SURREALIST EXPRESSION by TAYLOR NICOLE THEIS A THESIS Presented to the Department of Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts June 2014 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Taylor Nicole Theis Title: Duality, Symbolism, and Time: A Convergent Practice in Butoh and Surrealist Expression This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Fine Arts degree in the Department of Dance by: Christian Cherry Chairperson Steven Chatfield Member Shannon Mockli Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2014 ii This thesis and all materials contained herein are covered by the “Creative Commons By” license 2014 Taylor Nicole Theis iii THESIS ABSTRACT Taylor Nicole Theis Master of Fine Arts Department of Dance June 2014 Title: Duality, Symbolism, and Time: A Convergent Practice in Butoh and Surrealist Expression Butoh and Surrealism share some common features, three of which are: duality, symbolism and the manipulation of time. This project is an examination of the intersection of these elements and the development of a movement practice using these three, shared focusing lenses of Butoh and Surrealism, culminating in a performance. The methodology of this study sought to generate movement through improvisation and studio exercises based upon a melded Butoh/Surrealist universe developed through applied research in the convergent elements of duality, symbolism and the manipulation of time. -

Methods of Performer Training in Hijikata Tatsumi’S Butō Dance

BECOMING NOTHING TO BECOME SOMETHING: METHODS OF PERFORMER TRAINING IN HIJIKATA TATSUMI’S BUTŌ DANCE A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Tanya Calamoneri May 2012 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Luke Kahlich, Professor, Department of Dance Dr. Kariamu Welsh, Professor, Department of Dance Dr. Shigenori Nagatomo, Professor, Department of Religion Dr. Kimmika Williams-Witherspoon, Associate Professor, Department of Theater © Copyright 2012 by Tanya Calamoneri All Rights Reserved € ii ABSTRACT This study investigates performer training in ankoku butō dance, focusing specifically on the methods of Japanese avant-garde artist Hijikata Tatsumi, who is considered the co-founder and intellectual force behind this form. The goal of this study is to articulate the butō dancer’s preparation and practice under his direction. Clarifying Hijikata’s embodied philosophy offers valuable scholarship to the ongoing butō studies dialogue, and further, will be useful in applying butō methods to other modes of performer training. Ultimately, my plan is to use the findings of this study in combination with research in other body-based performance training techniques to articulate the pathway by which a performer becomes “empty,” or “nothing,” and what that state makes possible in performance. In an effort to investigate the historically-situated and culturally-specific perspective of the body that informed the development of ankoku butō dance, I am employing frameworks provided by Japanese scholars who figure prominently in the zeitgeist of 1950s and 1960s Japan. Among them are Nishida Kitarō, founder of the Kyoto School, noted for introducing and developing phenomenology in Japan, and Yuasa Yasuo, noted particularly for his study of ki energy. -

Richard Hawkins “To the House of Shibusawa” 14 September – 13 October 2018 Opening Reception on Friday, 14 September

Richard Hawkins “To the House of Shibusawa” 14 September – 13 October 2018 opening reception on Friday, 14 September, 7-9 pm In our second-floor gallery, we present “To the House of Shibusawa”, an exhibition of new and selected works conceived by Richard Hawkins in conversation with Robert Snowden. Here, Richard Hawkins muses on the close friendship between two historical Japanese cultural figures: Tatsumi Hijikata, founder of butoh, and Tatsuhiko Shibusawa, known as an idiosyncratic collector as well as the Japanese translator of the writings of Marquis de Sade, Joris-Karl Huysmans’s “Á Rebours”, Jean Genet’s “Querelle”, Georges Bataille’s “Erotism” and essays on Hans Bellmer. It becomes evident that the interests shared by these two friends – sensuality, dismemberment, nihilism, crime, perversity, abjection, French Décadence – helped foster the artform that became Hijikata’s “dance of darkness”. Richard Hawkins’s speculations on the Shibusawa-Hijikata connection revolve around two artefacts coinciding with the early days of butoh: Yokoo Tadanori’s poster for Hijikata’s “Rose Colored Dance” (1965) and the caricature of the decadent scholar in Yukio Mishima’s “Temple of the Dawn” (1970). In the latter, the increasingly- fascist Mishima portrays a character loosely based on Shibusawa, who represents what he considers the worst of culture descending into decline, a serial fantasizer of rituals called “murder theaters” – a more frenzied version of the perceived affect of butoh performance, but not so far from Hijikata’s own more privately imaginative wanderings. In the Tadanori poster, the designer emphasized less the performance’s title, “Rose Colored” and more its subtitle “A La Maison de Civecawa”, a mixture of Proust-allusion and absurdist French with the intent of making indisputably obvious the fruitful conversations Hijikata and Shibusawa must have had within the scholar’s cabinet-of-decadent-curiosities home and library. -

Special Affects : Compositing Images in the Bodies of Butoh

Special Affects Compositing Images in the Bodies ofBut oh Michael Homblow Submitted in accordance with the regulations for Master of Arts Thesis University of Technology, Sydney 2004 Certificate of Authorship I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Candidate '<::!-- 1 Acknowledgments Many thanks to my supervisors, Douglas Khan and Cathryn Vasseleu for their incredible patience and invaluable comments - Douglas during the formative phase of the research, and Cathryn for the writing and submission stages later on. I would also like to acknowledge my proofers for their corrections and suggestions (Stephen Gapps, Margaret Mahew, Andrew Hornblow and Stevie Bee). My utmost gratitude goes to the cast and crew of my short film,pneu babe/ (see credits on DVD, inside back cover), as well as my butoh teachers- in particular Min Tanaka, Kazuo and Yoshito Ohno, Gekidan Kaitaisha, Tony Yap and Yumi Umiumare. I would also like to acknowledge Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, Antonin Artaud, and Tatsumi Hijikata, for inspiring this research. Above all, I am forever indebted to my friends and family, in particular my martial-arts teacher, friend and mentor John Michelis, my confidant and 'wing-man' James Lygo, my parents Andrew and Daphne Horn blow for their tireless support and encouragement, my dear brother Douglas, and my fellow traveler in heart Mariela Laratro.