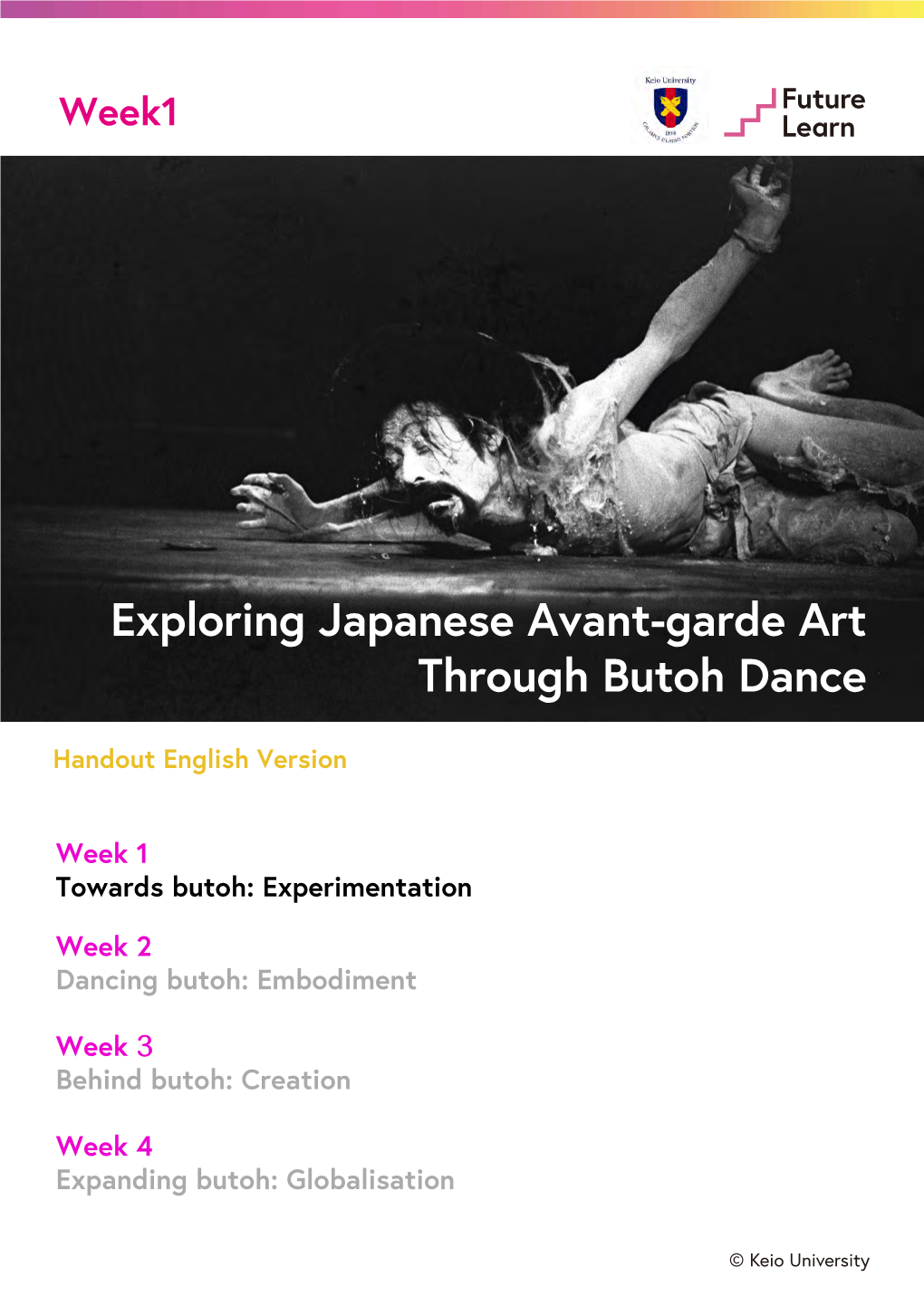

Exploring Japanese Avant-Garde Art Through Butoh Dance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Booxter Export Page 1

Cover Title Authors Edition Volume Genre Format ISBN Keywords The Museum of Found Mirjam, LINSCHOOTEN Exhibition Soft cover 9780968546819 Objects: Toronto (ed.), Sameer, FAROOQ Catalogue (Maharaja and - ) (ed.), Haema, SIVANESAN (Da bao)(Takeout) Anik, GLAUDE (ed.), Meg, Exhibition Soft cover 9780973589689 Chinese, TAYLOR (ed.), Ruth, Catalogue Canadian art, GASKILL (ed.), Jing Yuan, multimedia, 21st HUANG (trans.), Xiao, century, Ontario, OUYANG (trans.), Mark, Markham TIMMINGS Piercing Brightness Shezad, DAWOOD. (ill.), Exhibition Hard 9783863351465 film Gerrie, van NOORD. (ed.), Catalogue cover Malenie, POCOCK (ed.), Abake 52nd International Art Ming-Liang, TSAI (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover film, mixed Exhibition - La Biennale Huang-Chen, TANG (ill.), Catalogue media, print, di Venezia - Atopia Kuo Min, LEE (ill.), Shih performance art Chieh, HUANG (ill.), VIVA (ill.), Hongjohn, LIN (ed.) Passage Osvaldo, YERO (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover 9780978241995 Sculpture, mixed Charo, NEVILLE (ed.), Catalogue media, ceramic, Scott, WATSON (ed.) Installaion China International Arata, ISOZAKI (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover architecture, Practical Exhibition of Jiakun, LIU (ill.), Jiang, XU Catalogue design, China Architecture (ill.), Xiaoshan, LI (ill.), Steven, HOLL (ill.), Kai, ZHOU (ill.), Mathias, KLOTZ (ill.), Qingyun, MA (ill.), Hrvoje, NJIRIC (ill.), Kazuyo, SEJIMA (ill.), Ryue, NISHIZAWA (ill.), David, ADJAYE (ill.), Ettore, SOTTSASS (ill.), Lei, ZHANG (ill.), Luis M. MANSILLA (ill.), Sean, GODSELL (ill.), Gabor, BACHMAN (ill.), Yung -

Off Museum! Performance Art That Turned the Street Into 'Theatre,' Circa 1964 Tokyo

Performance Paradigm 2 (March 2006) Off Museum! Performance Art That Turned the Street into ‘Theatre,’ Circa 1964 Tokyo Midori Yoshimoto Performance art was an integral part of the urban fabric of Tokyo in the late 1960s. The so- called angura, the Japanese abbreviation for ‘underground’ culture or subculture, which mainly referred to film and theatre, was in full bloom. Most notably, Tenjô Sajiki Theatre, founded by the playwright and film director Terayama Shûji in 1967, and Red Tent, founded by Kara Jûrô also in 1967, ruled the underground world by presenting anti-authoritarian plays full of political commentaries and sexual perversions. The butoh dance, pioneered by Hijikata Tatsumi in the late 1950s, sometimes spilled out onto streets from dance halls. Students’ riots were ubiquitous as well, often inciting more physically violent responses from the state. Street performances, however, were introduced earlier in the 1960s by artists and groups, who are often categorised under Anti-Art, such as the collectives Neo Dada (originally known as Neo Dadaism Organizer; active 1960) and Zero Jigen (Zero Dimension; active 1962-1972). In the beginning of Anti-Art, performances were often by-products of artists’ non-conventional art-making processes in their rebellion against the artistic institutions. Gradually, performance art became an autonomous artistic expression. This emergence of performance art as the primary means of expression for vanguard artists occurred around 1964. A benchmark in this aesthetic turning point was a group exhibition and outdoor performances entitled Off Museum. The recently unearthed film, Aru wakamono-tachi (Some Young People), created by Nagano Chiaki for the Nippon Television Broadcasting in 1964, documents the performance portion of Off Museum, which had been long forgotten in Japanese art history. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Cutie and the Boxer, 1/11/2013

CUTIE AND THE BOXER, 1/11/2013 PRESENTS A FILM BY ZACHARY HEINZERLING CUTIE AND THE BOXER US|HD UK THEATRICAL RELEASE: 1 Nov, 2013 RUNNING TIME: 82 minutes Press Contact: Yung Kha T. 0207 831 7252 [email protected] Web: http://cutieandtheboxer.co.uk/ Twitter: @CutieAndBoxer Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/cutieandtheboxer CUTIE AND THE BOXER, 1/11/2013 SHORT SYNOPSIS A reflection on love, sacrifice, and the creative spirit, this candid New York story explores the chaotic 40- year marriage of renowned “boxing” painter Ushio Shinohara and his artist wife, Noriko. As a rowdy, confrontational young artist in Tokyo, Ushio seemed destined for fame, but met with little commercial success after he moved to New York City in 1969, seeking international recognition. When 19-year-old Noriko moved to New York to study art, she fell in love with Ushio—abandoning her education to become the wife and assistant to an unruly, husband. Over the course of their marriage, the roles have shifted. Now 80, Ushio struggles to establish his artistic legacy, while Noriko is at last being recognized for her own art—a series of drawings entitled “Cutie,” depicting her challenging past with Ushio. Spanning four decades, the film is a moving portrait of a couple wrestling with the eternal themes of sacrifice, disappointment and aging, against a background of lives dedicated to art. LONG SYNPOSIS Cutie and the Boxer is an intimate, observational documentary chronicling the unique love story between Ushio and Noriko Shinohara, married Japanese artists living in New York. Bound by years of quiet resentment, disappointments and missed professional opportunities, they are locked in a hard, dependent love. -

The Sought for Butoh Body: Tatsumi Hijikata's Cultural Rejection And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Waseda University Transcommunication Vol.3-1 Spring 2016 Graduate School of International Culture and Communication Studies Article The Sought For Butoh Body: Tatsumi Hijikata’s Cultural Rejection and Creation Julie Valentine Dind Abstract This paper studies the influence of both Japanese and Western cultures on Hijikata Tatsumi’s butoh dance in order to problematize the relevance of butoh outside of the cultural context in which it originated. While it is obvious that cultural fusion has been taking place in the most recent developments of butoh dance, this paper attempts to show that the seeds of this cultural fusion were already present in the early days of Hijikata’s work, and that butoh dance embodies his ambivalence toward the West. Moreover this paper furthers the idea of a universal language of butoh true to Hijikata’s search for a body from the “world which cannot be expressed in words”1 but only danced. The research revolves around three major subjects. First, the shaping power European underground literature and German expressionist dance had on Hijikata and how these influences remained present in all his work throughout his entire career. Secondly, it analyzes the transactions around the Japanese body and Japanese identity that take place in the work of Hijikata in order to see how Western culture might have acted as much as a resistance as an inspiration in the creation of butoh. Third, it examines the unique aspects of Hijikata’s dance, in an attempt to show that he was not only a product of his time but also aware of the shaping power of history and actively fighting against it in his quest for a body standing beyond cultural fusion or history. -

By Michio Arimitsu from Voodoo to Butoh

From Voodoo to Butoh: Katherine By Michio Arimitsu Dunham, Hijikata Tatsumi, and Trajal Harrell’s Transcultural Refashioning of “Blackness” I said black is . an’ black ain’t . Black will git you . put butoh aesthetics and techniques in dialogue with an’ black won’t. [. .] Black will make you . or black those of voguing, has given us a tantalizing glimpse will unmake you. of what’s to come.5 Rather than directly engaging – Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952) with Harrell’s ongoing refashioning of butoh, I want to underscore the cultural significance of his endeavor by I remember Hijikata’s body—a northern body, the skin situating it in the history of Afro-Asian performative very white, the hair standing out very black against it. exchange across the Pacific. More specifically, however, – Donald Richie, “On Tatsumi Hijikata” (1987) I want to shed a new light on an encounter between Hijikata and Katherine Dunham (1909–2006), the pioneering African American modern dancer, at a Introduction: What Would Have Happened if Hijikata decisive moment before Hijikata’s “dance of darkness/ Tatsumi Had Not Seen Katherine Dunham in 1957? blackness” was born. As I argue, Dunham’s voodoo- Like a skilled designer who duly respects the traditions, inspired performance, along with torrential imports of but is never afraid of pushing the boundaries of the other African American/Afro-Caribbean images and fashion world, Trajal Harrell fascinates and provokes cultural forms into post-WWII Japan, had a much more his audience by tailoring seemingly disparate materials crucial role in the early aesthetics of butoh than has from near and far to his own eclectic choreography. -

Galleria Massimo Minini

GALLERIA MASSIMO MININI Via Apollonio 68 – 25128 Brescia tel. 030383034 [email protected] www.galleriaminini.it shusaku arakawa seventeen works Can art be put at the service of the mind? Marcel Duchamp made this a principle, Shusaku Arakawa made it a reality. Arakawa, an artist who was anything but local in his thinking, left Japan to plunge into the New York scene of the ’60s. With one goal: to create mental art, a science of the imagination that conceives and conveys two civilizations; a new form of thought that blends together two opposite worlds: analytic and compendious, discriminating and absolutizing, impersonal and subjective. He drew on concrete reality, on visual images anchored to the world around them, objects described through mental diagrams—shadows at first, then graphic renderings that follow geometric rules. Since the visible world is impossible to capture with the sole aid of geometry, he proceeded by meditation, infusing atonal fields with pure spirit and trading images for words. The names of things conjure up enigmatic outlines, similar forms refer to different objects, color is added to give substance to the arrangement of signs. What we see on the canvas before us is not a fixed image, but a visualization of thought in movement. Shusaku Arakawa (Nagoya, July 6, 1936 – Manhattan, May 18, 2010) was an artist and architect, one of the best-known and most influential figures in Japanese art. His major shows have included: Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 1958; MOMA, New York, 1966; 35th Venice Biennale, 1970; Neue National Galerie, Berlin, 1972; Städtische Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, 1977; Solomon R. -

Translating the Narrative: an Approach to the Conceptual Design of a Contemporary Orthodox Christian Church

Translating the Narrative: an Approach to the Conceptual Design of a Contemporary Orthodox Christian Church by Anastasiya Burchevska A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master In Architecture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016 Anastasiya Burchevska Abstract The conceptual design approach is meant to address the challenges faced by an architect when it comes to creating a contemporary Orthodox Christian church. The design would have to adapt to various urban, architectural and social conditions that significantly differ from those of the previous eras. This design approach establishes a framework that allows the integration of the various design aspects of such a complex architectural object as the Orthodox Christian church at the conceptual design stage. This thesis focuses on the creation of the architectural narrative or the information layer integrated in the building design as a method of communicating a theological concept in terms applicable to the current cultural and temporal context. ii Table of Contents Translating the Narrative: an Approach to the Conceptual Design of a Contemporary Orthodox Christian Church ................................................................................................. i Abstract ......................................................................................................................... ii Table of Contents ........................................................................................................ -

Recovering the Body and Expanding the Boundaries of Self in Japanese

Contemporary Theatre Review, Vol. 20(1), 2010, 56–67 Recovering the Body and Expanding the Boundaries of Self in Japanese 1. Ankoku translates as Butoh: Hijikata Tatsumi, Georges ‘sheer’, ‘utter’ or ‘total’ darkness. 2. Reference is being made Bataille and Antonin Artaud here to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki of 1945, which were followed by the Catherine Curtin profound humiliation of American occupation. Note that Hijikata was a teenager during this time; he was born in March 1928 and died in January 1986. Ankoku Butoh (the Dance of Utter Darkness),1 a revolutionary dance form 3. Hijikata rebelled against the orthodoxy of the created by Hijikata Tatsumi in the late 1950s, emerged in the new Tokyo Shingeki establishment. 2 This new theatre was a that developed out of the dark, post-nuclear war years. Implicit in movement away from Hijikata’s work was a powerful critique of the cultural hegemony, rationa- the decadence, grotesqueness and lity and increasing individualism that were the outcomes of intensifying fantasy of traditional western influence. In his dance, Hijikata allowed alternative narratives to Kabuki, which offered close interaction with emerge, freeing the subject to take up new positions that would destabilise the audience and a manifold sensuality. notions of separation, individual personality and coherent identity. He 4. In the late nineteenth ironically incorporated elements from a pre-modern Japanese sensibility century, constraints were imposed on androgyny and appealed to those western artists and thinkers who preferred the and cross-dressing in Gnostic principles of darkness as potent alternatives to the privileging of traditional Kabuki and Noh theatre, with the clarity and light within their own traditions. -

Fergus Mccaffrey, St. Barth Natsuyuki Nakanishi / Jiro Takamatsu August 6

Fergus McCaffrey, St. Barth Natsuyuki Nakanishi / Jiro Takamatsu August 6 – September 15, 2015 Fergus McCaffrey, St. Barth is proud to present an exhibition of paintings and works on paper by two of the most influential Japanese artist. Natsuyuki Nakanishi / Jiro Takamatsu will be on view from August 6 - September 15, with an opening reception from 6:00 – 8:00 PM on Thursday, August 6. Natsuyuki Nakanishi and Jiro Takamatsu formed the legendary collective Hi Red Center in 1963 along with Genpei Akasegawa; named from the English translations of the first characters of their surnames-- “taka” (high), “aka” (red) and “naka” (center). The movement was short-lived, but produced performance pieces involving the community and participants in Tokyo, which sought to eliminate the boundary between art and life. After the movement ended in 1964, Nakanishi and Takamatsu worked individually in order to pursue their own artistic practice. In his over 50-year career, Nakanishi has constantly challenged the role of the artist and his relation to art making. Describing his art as coming to its own fruition, Nakanishi works to deconstruct formal elements to recompose them into abstract forms. The drawings featured in the exhibition each have their own individual development, yet are explorations of a continuous idea. Though minimal in nature, Nakanishi’s works hold much depth and investigate the abstract process that gravity imposes on the medium on a flat plane. Perhaps one of the most influential artists working in Japan during the 1960s and 1970s, Jiro Takamatsu altered the evolution of conceptual art in Japan as an artist and theorist, dominating Japanese artistic discourse during those years. -

Existence Beyond Condition This Text Is Excerpted from a Forthcoming

Existence Beyond Condition This text is excerpted from a forthcoming anthology of newly translated writings by Kishio Suga, edited by Andrew Maerkle and published by Skira Editore and Blum & Poe. Introduction by Andrew Maerkle In 1970 Bijutsu Techō dedicated the featured content of its February issue to the voices of emerging artists. Subjects included Susumu Koshimizu, Lee Ufan, Katsuhiko Narita, Nobuo Sekine, Katsuro Yoshida, and Suga, who all appeared together in a roundtable discussion. 1 The year prior, in 1969, these artists had made their mark at major exhibitions, such as the 9th Contemporary Art Exhibition of Japan at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum and the annual Trends in Contemporary Art exhibition at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto. Not participating in either, Suga was the lone exception, although his solo exhibition in October 1969 at Tamura Gallery, where he presented the work Parallel Strata, caught the eye of influential critics such as Toshiaki Minemura. Indeed, Suga was on the cusp of his breakthrough. Later in 1970, he would be included in Trends in Contemporary Art in Kyoto, as well as another important annual survey, the Artists Today exhibition organized by the Yokohama Civic Art Gallery, and August 1970: Aspects of New Japanese Art at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. Additionally, he won the grand prize at the 5th Japan Art Festival exhibition, which traveled to the Guggenheim Museum in New York under the title Contemporary Japanese Art. It was a sign of things to come, then, that Suga was chosen to contribute one of two long essays that led the roundtable, the other being Lee Ufan’s “In Search of Encounter.”2 Full of dense rhetoric, “Existence beyond Condition” is one of Suga’s most challenging texts to unpack. -

2012 SUNY New Paltzdownload

New York Conference on Asian Studies September 28 –29, 2012 ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ NYCAS 12 Conference Theme Contesting Tradition State University of New York at New Paltz Executive Board New York Conference on Asian Studies Patricia Welch Hofstra University NYCAS President (2005-2008, 2008-2011, 2011-2014) Michael Pettid (2008-2011) Binghamton University, SUNY Representative to the AAS Council of Conferences (2011-2014) Kristin Stapleton (2008-2011, 2011-2014) University at Buffalo, SUNY David Wittner (2008-2011, 2011-2014) Utica College Thamora Fishel (2009-2012) Cornell University Faizan Haq (2009-2012) University at Buffalo, SUNY Tiantian Zheng (2010-2013) SUNY Cortland Ex Officio Akira Shimada (2011-2012) David Elstein (2011-2012) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS 12 Conference Co-Chairs Lauren Meeker (2011-2014) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Treasurer Ronald G. Knapp (1999-2004, 2004-2007, 2007-2010, 2010-2013) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Executive Secretary The New York Conference on Asian Studies is among the oldest of the nine regional conferences of the Association for Asian Studies (AAS), the largest society of its kind in the world. NYCAS is represented on the Council of Conferences, one of the sub-divisions of the governing body of the AAS. Membership in NYCAS is open to all persons interested in Asian Studies. It draws its membership primarily from New York State but welcomes participants from any region interested in its activities. All persons registering for the annual meeting pay a membership fee to NYCAS, and are considered members eligible to participate in the annual business meeting and to vote in all NYCAS elections for that year.