Dead Cat Alley: an Archaeological Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Historical Experience of Labor: Archaeological Contributions To

4 Barbara L. Voss (芭芭拉‧沃斯) Pacific Railroad, complained about the scarcity of white labor in California. Crocker proposed that Chinese laborers would be hardworking The Historical Experience and reliable; both he and Stanford had ample of Labor: Archaeological prior experience hiring Chinese immigrants to work in their homes and on previous business Contributions to Interdisciplinary ventures (Howard 1962:227; Williams 1988:96). Research on Chinese Railroad construction superintendent J. H. Stro- Railroad Workers bridge balked but relented when faced with rumors of labor organizing among Irish immi- 劳工的历史经验:考古学对于中 grants. As Crocker’s testimony to the Pacific 国铁路工人之跨学科研究的贡献 Railway Commission later recounted: “Finally he [Strobridge] took in fifty Chinamen, and a ABSTRACT while after that he took in fifty more. Then, they did so well that he took fifty more, and he Since the 1960s, archaeologists have studied the work camps got more and more until we finally got all we of Chinese immigrant and Chinese American laborers who could use, until at one time I think we had ten built the railroads of the American West. The artifacts, sites, or twelve thousand” (Clark 1931:214; Griswold and landscapes provide a rich source of empirical informa- 1962:109−111; Howard 1962:227−228; Chiu tion about the historical experiences of Chinese railroad 1967:46; Kraus 1969a:43; Saxton 1971:60−66; workers. Especially in light of the rarity of documents Mayer and Vose 1975:28; Tsai 1986; Williams authored by the workers themselves, archaeology can provide 1988:96−97; Ambrose 2000:149−152; I. Chang direct evidence of habitation, culinary practices, health care, social relations, and economic networks. -

Yolo County Cannabis Land Use Ordinance Draft Environmental

Ascent Environmental Cultural Resources 3.5 CULTURAL RESOURCES This section analyzes and evaluates the potential impacts of the project on known and unknown cultural resources as a result of adoption and implementation of the proposed CLUO, including issuance of subsequent Cannabis Use Permits pursuant to the adopted CLUO. Cultural resources include districts, sites, buildings, structures, or objects generally older than 50 years and considered to be important to a culture, subculture, or community for scientific, traditional, religious, or other reasons. They include prehistoric resources, historic-era resources, and tribal cultural resources (the latter as defined by AB 52, Statutes of 2014, in PRC Section 21074). This section also analyzes archaeological, historical, and tribal cultural resources. Paleontological resources are discussed in Section 3.7, “Geology and Soils.” Archaeological resources are locations where human activity has measurably altered the earth or left deposits of prehistoric or historic-era physical remains (e.g., stone tools, bottles, former roads, house foundations). Historical (or architectural or built environment) resources include standing buildings (e.g., houses, barns, outbuildings, cabins), intact structures (e.g., dams, bridges, wells), or other remains of human’s alteration of the environment (e.g., foundation pads, remnants of rock walls). Tribal cultural resources were added as a distinct resource subject to review under CEQA, effective January 1, 2015, under AB 52. Tribal cultural resources are sites, features, places, cultural landscapes, sacred places, and objects with cultural value to a California Native American tribe that are either included or determined to be eligible for inclusion in the California Register of Historical Resources (CRHR) or local registers of historical resources. -

California State Parks

1 · 2 · 3 · 4 · 5 · 6 · 7 · 8 · 9 · 10 · 11 · 12 · 13 · 14 · 15 · 16 · 17 · 18 · 19 · 20 · 21 Pelican SB Designated Wildlife/Nature Viewing Designated Wildlife/Nature Viewing Visit Historical/Cultural Sites Visit Historical/Cultural Sites Smith River Off Highway Vehicle Use Off Highway Vehicle Use Equestrian Camp Site(s) Non-Motorized Boating Equestrian Camp Site(s) Non-Motorized Boating ( Tolowa Dunes SP C Educational Programs Educational Programs Wind Surfing/Surfing Wind Surfing/Surfing lo RV Sites w/Hookups RV Sites w/Hookups Gasquet 199 s Marina/Boat Ramp Motorized Boating Marina/Boat Ramp Motorized Boating A 101 ed Horseback Riding Horseback Riding Lake Earl RV Dump Station Mountain Biking RV Dump Station Mountain Biking r i S v e n m i t h R i Rustic Cabins Rustic Cabins w Visitor Center Food Service Visitor Center Food Service Camp Site(s) Snow Sports Camp Site(s) Geocaching Snow Sports Crescent City i Picnic Area Camp Store Geocaching Picnic Area Camp Store Jedediah Smith Redwoods n Restrooms RV Access Swimming Restrooms RV Access Swimming t Hilt S r e Seiad ShowersMuseum ShowersMuseum e r California Lodging California Lodging SP v ) l Klamath Iron Fishing Fishing F i i Horse Beach Hiking Beach Hiking o a Valley Gate r R r River k T Happy Creek Res. Copco Del Norte Coast Redwoods SP h r t i t e s Lake State Parks State Parks · S m Camp v e 96 i r Hornbrook R C h c Meiss Dorris PARKS FACILITIES ACTIVITIES PARKS FACILITIES ACTIVITIES t i Scott Bar f OREGON i Requa a Lake Tulelake c Admiral William Standley SRA, G2 • • (707) 247-3318 Indian Grinding Rock SHP, K7 • • • • • • • • • • • (209) 296-7488 Klamath m a P Lower CALIFORNIA Redwood K l a Yreka 5 Tule Ahjumawi Lava Springs SP, D7 • • • • • • • • • (530) 335-2777 Jack London SHP, J2 • • • • • • • • • • • • (707) 938-5216 l K Sc Macdoel Klamath a o tt Montague Lake A I m R National iv Lake Albany SMR, K3 • • • • • • (888) 327-2757 Jedediah Smith Redwoods SP, A2 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • (707) 458-3018 e S Mount a r Park h I4 E2 t 3 Newell Anderson Marsh SHP, • • • • • • (707) 994-0688 John B. -

Cultural, Paleontological, and Tribal Cultural Resources

Chapter 7—Cultural, Paleontological, and Tribal Cultural Resources 7.1 Introduction This chapter describes the existing conditions (environmental and regulatory) and assesses the potential cultural, paleontological, and tribal resources impacts of the 2020 Metropolitan Transportation Plan/Sustainable Communities Strategy (proposed MTP/SCS). Where necessary and feasible, mitigation measures are identified to reduce these impacts. The information presented in this chapter is based on review of existing and available information and is regional in scope. Data, analysis, and findings provided in this chapter were considered and prepared at a programmatic level. For consistency with the 2016 MTP/SCS EIR, paleontological resources are addressed in this chapter even though these resources are grouped with geology and soils in Appendix G of the CEQA Guidelines (SACOG 2016). Impacts to unique geologic features are addressed in Chapter 9 – Geology, Soils, Seismicity, and Mineral Resources. Cultural resources include archaeological sites or districts of prehistoric or historic origin, built environment resources older than 50 years (e.g., historic buildings, structures, features, objects, districts, and landscapes), and traditional or ethnographic resources, including tribal cultural resources, which are a separate category of cultural resources under CEQA. Paleontological resources include mineralized, partially mineralized, or unmineralized bones and teeth, soft tissues, shells, wood, leaf impressions, footprints, burrows, and microscopic remains that are more than 5,000 years old and occur mainly in Pleistocene or older sedimentary rock units. In response to the Notice of Preparation (NOP), SACOG received comments related to cultural and tribal cultural resources from the Native American Heritage Commission (NAHC) and United Auburn Indian Community of the Auburn Rancheria. -

Willamette Valley Voices: Connecting Generations

Willamette Valley Voices: Connecting Generations A publication of the Willamette Heritage Center at The Mill Digital Proofer Editor: Keni Sturgeon, Willamette Heritage Center Editorial board: Willamette Valley Vo... Hannah Marshall, Western Oregon University Authored by Willamette Heritag... Duke Morton, Western Oregon University 7.0" x 10.0" (17.78 x 25.40 cm) Jeffrey Sawyer, Western Oregon University Black & White on White paper Amy Vandegrift, Willamette Heritage Center 78 pages ISBN-13: 9781478201755 ISBN-10: 1478201754 Please carefully review your Digital Proof download for formatting, grammar, and design issues that may need to be corrected. We recommend that you review your book three times, with each time focusing on a different aspect. Check the format, including headers, footers, page 1 numbers, spacing, table of contents, and index. 2 Review any images or graphics and captions if applicable. 3 Read the book for grammatical errors and typos. Once you are satisfied with your review, you can approve your proof and move forward to the next step in the publishing process. To print this proof we recommend that you scale the PDF to fit the size © 2012 Willamette Heritage Center at The Mill of your printer paper. Willamette Valley Voices: Connecting Generations is published biannually – summer and winter – by the Willamette Heritage Center at The Mill, 1313 Mill Street SE, Salem, OR 97301. Nothing in the journal may be reprinted in whole or part without written permission from the publisher. Direct inquiries to Curator, Willamette Heritage Center, 1313 Mill Street SE, Salem, OR 97301 or email [email protected]. www.willametteheritage.org Willamette Valley Voices: Connecting Generations In This Issue A Journal of Willamette Valley History This edition of Willamette Valley Voices: Connecting Generations is the first of the Willamette Volume 1 Summer 2012 Number 1 Heritage Center’s new biannual publication. -

Block 14 Memorial Garden Gains Funding Page 3

Spring 2021 Our Big Backyard Our Big Parks and nature news and events and news nature and Parks “There's so much history that's left to be told.” Block 14 memorial garden gains funding page 3 What’s inside Cover story Miyo Iwakoshi, on left, was the first Japanese immigrant Parks and nature news and events and news nature and Parks to Oregon. She is among the incredible women buried at Metro's historic cemeteries. page 8 Oak map Mapping nearly every oak in the region takes a team, and patience. Our Big Backyard Our Big page 6 oregonmetro.gov TABLE OF CONTENTS Share your nature and win! Share your nature 2 Parks and nature news 3 Mussel bay 4 Wildflower field guide 5 One oak at a time 6 Finding her story 8 Tools for living 11 Coloring: Oregon white oak canopy 12 Winner: Rick Hafele, Wilsonville If you picnic at Blue Lake or take your kids to the At Graham Oaks Nature Park, I walked by this patch of lupine. I tried to imagine what they’d look like with a Oregon Zoo, enjoy symphonies at the Schnitz or auto dramatic sunrise. I finally saw my chance and arrived in time to set up just as the clouds lifted enough for the first shows at the convention center, put out your trash or rays of morning sunlight to do their thing. Follow Rick on Instagram @rickhafele drive your car – we’ve already crossed paths. So, hello. We’re Metro – nice to meet you. In a metropolitan area as big as Portland, we can do a lot of things better together. -

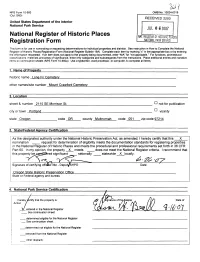

Vv Signature of Certifying Offidfel/Title - Deput/SHPO Date

NPSForm 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JUL 0 6 2007 National Register of Historic Places m . REG!STi:ffililSfGRicTLA SES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SERVICE — This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instruction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classifications, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Lone Fir Cemetery other names/site number Mount Crawford Cemetery 2. Location street & number 2115 SE Morrison St. not for publication city or town Portland vicinity state Oregon code OR county Multnomah code 051 zip code 97214 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties | in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR [Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_ meets __does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Lone Fir Cemetery Recommendations Mar 2010 PDF Open

LONE FIR CEMETERY EXISTING CONDITIONS, RECOMMENDATIONS, AND FUNDING SOURCES Portland Metro Sustainability Center Lango Hansen Landscape Architects Historical Research Associates KPFF Consulting Engineers Reyes Engineering 2008 Lone Fir Cemetery Existing Conditions Lone Fir Cemetery contains many historical elements which have significance both as defined by the National Register of Historic Places and the Secretary of the Interior. As part of its listing on the National Register of Historic Places, a number of contributing resources (CR) are defined, including the site of the cemetery itself. These contributing resources that were indicated in the National Register submission are indicated as such below. Using the Secretary of the Interior’s “Guidelines for Rehabilitating Cultural Landscapes” a number of character defining elements (CD) have also been indicated. Character defining elements convey the historical, cultural or architectural values of the cultural landscape. Additional items listed below are considered “functional” (F) in that they are more recent additions to the cemetery, and are not contributing resources or character defining features. As part of the master plan of the cemetery, items listed as contributing resources and character defining elements should be sensitively restored and preserved. Items listed as functional elements should be improved to be of consistent quality and materials as used elsewhere in the cemetery. SITE • Lone Fir Cemetery - CR STRUCTURES • Macleay Mausoleum – CR • Maintenance Structure Near Macleay -

Archaeology and Architecture of the Overseas Chinese: a Bibliography

ARCHAEOLOGY AND ARCHITECTURE OF THE OVERSEAS CHINESE: A BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled by Peter D. Schulz and Rebecca Allen Emigration from southeastern China over the last few centuries represents one of the most important population movements of modern history. Deriving primarily from Guangdong and Fujian, emigrants were attracted first to Taiwan, then southeast Asia, North America, and Australasia, as well as many other areas of the globe, where they occupied an amazing variety of social and economic roles. This movement has attracted the attention of Western observers since at least the middle of the 19th century, when overseas Chinese (Huáqiáo) immigrants began arriving in the gold fields of California and Australia, and soon aroused the interest of Western social scientists. Beginning with early descriptive studies (Ratzel 1876), these observers have dealt with a variety of issues, including ethnicity, sojourner status, migrant and industrial labor, middleman minorities and entrepreneurial capitalism. In California alone, Huáqiáo immigrants and their descendents played crucial roles in the development of so many industries that one important early historical study (Chinn et al. 1969) devoted considerable effort describing only the major ones. In the mid-1990s, the SHA published a series of bibliographies that documented archaeological references concerning the immigrant experience in North America. This bibliography is intended to be an extension of that series. It is inevitable that any bibliographic effort involving an active area of research will be immediately out of date. For that reason, we are publishing these references on the SHA website, where readers will have immediate and efficient access, and we can periodically update the information. -

Faunal Remains As Markers of Ethnic Identity

FAUNAL REMAINS AS MARKERS OF ETHNIC IDENTITY: THE PHILADELPHIA HOUSE AS A CASE STUDY OF GERMAN-AMERICAN ETHNICITY ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Anthropology ____________ by © Jennifer Marie Muñoz 2011 Fall 2011 FAUNAL REMAINS AS MARKERS OF ETHNIC IDENTITY: THE PHILADELPHIA HOUSE AS A CASE STUDY OF GERMAN-AMERICAN ETHNICITY A Thesis by Jennifer Marie Muñoz Fall 2011 APPROVED BY THE DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND VICE PROVOST FOR RESEARCH: _________________________________ Eun K. Park, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: ______________________________ _________________________________ Guy Q. King, Ph.D. Antoinette Martinez, Ph.D., Chair Graduate Coordinator _________________________________ Frank E. Bayham, Ph.D. PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this thesis may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to two people. For Tad, my greatest champion, my best friend, my light and my love. You taught me how to restore faith in myself when I needed it the most. You have seen me at my best and my worst, and yet you still stand beside me, supporting me with the kind of maturity and optimism that I did not known could exist in a single person. Thank you for always believing in me, and for supporting my thesis work with the patience of a saint. And to my Mookie, my sweet mom. By your example, I have learned that a mother’s love for her daughter transcends even the greatest hardships that life can present. -

GLO Surveyors Interment Data Arranged Alphabetically

GLO Surveyors Interment Data Arranged Alphabetically 12/11/2017 Surveyor Age Burial Tombstone St. City Cemetery Aall, Nicolai 1875-1958 Died in Seattle, WA Seattle Benjamin cremated Abbott, 1829-1902 Died in Olympia, No Marker for him WA Tumwater Masonic Lewis WA. His second present at either of Cemetery Gallatin wife, Helen is buried his wife's graves. in Masonic Gps of likely Cemetery, gravesite beside his Tumwater. His wife at Masonic obituary lists his Cemetery by Jerry burial place as Olson: Masonic Cemetery. There is a Lewis B. 47°00'51.1" Abbott with an 1855 122°53'47.8" death date buried ± 10 ft. just North of Helen Abbott at Masonic Cemetery, without a marker. Abbott, 1834-1894 Died in Waukegan, See Jerry Olson IL Waukegan Oakwood Richard Illinois, buried in Cemetery Aroy Oakwood Cemetery, Waukegan Illinois Adams, 1847-1894 Committed suicide See Jerry Olson WA Tacoma Tacoma Alexander with a gunshot to the Cemetery Marshall head in Tacoma, Gps of tombstone by buried in Tacoma Jerry Olson: Cemetery, Tacoma, Washington, Lot 8, 47°12'45.8" Block B, Section 1, 122°28'54.7" space 1 ± 11 ft. Allen, Bryan 1877-1952 Died in Olympia, See Jerry Olson WA Tumwater Masonic Hunt "Bun" buried in Masonic Cemetery Cemetery, Gps of grave marker Tumwater, by Jerry Olson: Washington, Row 6, Lot 2, Block 129 47°00'55.3" 122°53'53.5" ± 6 ft. Surveying North of the River, Second Edition copyright 2017, Jerry Olson Interment Data A 705 Surveyor Age Burial Tombstone St. City Cemetery Allen, 1839-1910 Died in Olympia, see Jerry Olson WA Olympia Thomas Washington, buried Newton in Masonic Cemetery, Tumwater, Washington. -

The Golden State Robert Louis Stevenson SP, I2 U U U (707) 942-4575 Ciccittyty Samuel P

ON THE WAY TO THE PARK ON THE WAY TO THE PARK Getting here should be half the fun - not a headache. Getting here should be half the fun - not a headache. ODWALLA ODWALLA TheO D WA Ar L Lt Aful Mix of The Artf ThTea Asrttefu al Mnidx Nofutrition ul Mix of aste and trition Taste and Nutrition T Nu WHEN YOU’RE AT THE PARK ODWALLA & THE TIP 4 To warm up sunset or sunrise scenes, adjust your WHEN YOU’RE AT THE PARK Us Canon Outdoor camera’s White Balance settings. Auto White Balance’s WHEN YOU’RE AT THE PARK ODWALLA ENVIRONMENT LeLett Us PPlalantn At A job is to remove color from the light in photos, and a sunrise or sunset is where you WANT brilliant oranges For more than ree For u! PHOTO TIPS and reds. A switch to the Cloudy or Shade setting will Chris Anderson 25 years, Odwalla Tree ForYo ! he Ar As part ofT our on-going commitment to you and toY Motherou TIP 1 Use your autofocus precisely, even in landscape T rt warm up colors, for a rich effect. I’m here to save you money. And keep you safe. Let Us fu f has been committed I’m here to save you money. And keep you safe. Earth, we want to plant trees in your state parks! Here’s how: pictures. Pick out one primary subject in the scene, and I’m here to save you money. And keep you safe. Pla l Mix of I’m here to save you money.