2002 Opinions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Lives: Engaging People, Places and Systems to Improve Health Outcomes, 2014

Changing Lives Engaging People, Places and Systems to Improve Health Outcomes 2014 Highmark Foundation Giving Report www.highmarkfoundation.org The image on the cover of this report is meant to represent positive change and improvement, and speaks directly to the positive impact the Foundation has on the people and communities it serves. 1 Changing Lives: Engaging People, Places and Systems to Improve Health Outcomes Mission The Highmark Foundation is a private, charitable organization of Highmark Inc. that supports initiatives and programs aimed at improving community health. The Foundation’s mission is to improve the health, well-being and quality of life for individuals who reside in the communities served by Highmark Inc. The Foundation strives to support evidence-based programs that impact multiple counties and work collaboratively to leverage additional funding to achieve replicable models. For more information, visit www.highmarkfoundation.org. Contents Board Members and Officers 3 Introduction to the Highmark Foundation 4 Highmark Foundation Grants 8 Highmark Foundation in the News 18 2014 Highmark Foundation Giving Report 1 The Highmark Foundation was established in 2000 to improve The initiatives funded by the Foundation fall within four the health and well-being of people living in the diverse categories: chronic disease, family health, service delivery communities served by Highmark Inc. We do this by awarding systems and healthy communities. These are the areas where high-impact grants to charitable organizations, hospitals and we have seen the greatest needs and remain our primary schools that develop programs to advance community health. areas of focus. The Foundation’s greatest successes are strong partnerships As we look ahead to 2015 and beyond, the Foundation with regional, national and global organizations with similar remains committed to improving the health and well-being missions, working to raise awareness of community health of communities throughout Pennsylvania and West Virginia. -

In Re Victor Romm

United States Bankruptcy Court Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division Transmittal Sheet for Opinions for Publishing and Posting on Website Will this Opinion be Published? No Bankruptcy Caption: In re Victor Romm Bankruptcy No. 05 B 46897 Adversary Caption: Pearle Vision, Inc. and Pearle, Inc. v. Victor Romm Adversary No. 06 A 69 Date of Issuance: December 13, 2006 Judge: A. Benjamin Goldgar Appearance of Counsel: Attorney for debtor Victor Romm: John O. Noland, Jr., Chicago, IL Attorneys for Pearle Vision, Inc. and Pearle Inc.: John D. Silk, Rothschild, Barry & Myers, Chicago, IL, Craig P. Rieders, Genovese Joblove & Battista, P.A., Miami, FL UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION In re: ) Chapter 7 ) VICTOR ROMM, ) No. 05 B 46897 ) Debtor. ) ______________________________________ ) ) PEARLE VISION, INC., and PEARLE, ) INC., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) No. 06 A 69 ) VICTOR ROMM, ) ) Defendant. ) Judge Goldgar MEMORANDUM OPINION Before the court for ruling is the motion of debtor Victor Romm to dismiss the first amended adversary complaint of plaintiffs Pearle Vision, Inc. and Pearle, Inc. (collectively “Pearle”). For the reasons that follow, the motion to dismiss will be denied. 1. Background In deciding Romm’s motion, the court has considered both the first amended complaint and its exhibits, taking all facts alleged to be true. See Hollander v. Brown, 457 F.3d 688, 690 (7th Cir. 2006). The court has also reviewed the debtor’s petition and schedules, along with the district court’s docket and papers filed in the related action styled Pearle Vision, Inc., et al. v. Romm, et al., No. 04 C 4349 (N.D. -

Pennsylvania's Largest Employers (At Least 1,000 Employees)

Pennsylvania's Largest Employers (At Least 1,000 Employees) 1st Quarter, 2018 Combined Government Ownerships Center for Workforce Information & Analysis (877) 4WF-DATA • www.workstats.dli.pa.gov • [email protected] September 2018 Rank Employer Rank Employer 1 Federal Government 51 ACME Markets Inc 2 State Government 52 Aerotek Inc 3 Wal-Mart Associates Inc 53 Geisinger Medical Center 4 Trustees of the University of PA 54 Reading Hospital 5 City of Philadelphia 55 Dolgencorp LLC 6 Pennsylvania State University 56 Carnegie Mellon University 7 Giant Food Stores LLC 57 Abington Memorial Hospital 8 School District of Philadelphia 58 FedEx Ground Package System Inc 9 UPMC Presbyterian Shadyside 59 Highmark Inc 10 United Parcel Service Inc 60 Kohl's Department Stores Inc 11 PNC Bank NA 61 Rite Aid of Pennsylvania Inc 12 University of Pittsburgh 62 Marmaxx Operating Corporation 13 Lowe's Home Centers LLC 63 The Hershey Company 14 Weis Markets Inc 64 Wells Fargo NA 15 The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia 65 Temple University Hospital Inc 16 Comcast Cablevision Corp (PA) 66 York Hospital 17 Home Depot USA Inc 67 SmithKline Beecham Corporation 18 PA State System of Higher Education 68 Starbucks Corporation 19 Giant Eagle Inc 69 Boscov's Department Store LLC 20 Amazon.com DEDC LLC 70 School District of Pittsburgh 21 The Vanguard Group Inc 71 UPMC Pinnacle Hospitals 22 Target Corporation 72 Geisinger Clinic 23 Merck Sharp & Dohme Corporation 73 Dick's Sporting Goods Inc 24 Western Penn Allegheny Health 74 Hershey Entertainment & Resorts Co 25 -

Two Locals Perish in Car Crash

Mailed free to requesting homes in Eastford, Pomfret & Woodstock Vol. IV, No. 19 Complimentary to homes by request (860) 928-1818/e-mail: [email protected] ‘Courage is the price that life exacts for granting peace.’ FRIDAY, JANUARY 23, 2009 Two Quiet Corner observes historic inauguration day locals OBAMA SWORN IS AS 44TH U.S. PRESIDENT BY MATT SANDERSON regation, and emerged from that VILLAGER STAFF WRITER dark chapter stronger and united, Barack Obama was sworn in as we cannot help but believe that the perish in the 44th president of the United old hatreds shall someday pass; that States Tuesday, Jan. 20, at the presi- the lines of tribe shall soon dis- dential inauguration, and has solve. …” moved into his new residence with It was estimated that more than car crash his family at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. two million people crowded the in Washington, D.C. He is the first National Mall and the parade route U.S. president of African-American along Pennsylvania Avenue just to AREA’S FIRST descent. be a part of the occasion. “… We are shaped by every lan- After being sworn in and reciting FATALITIES IN 2009 guage and culture,” said Obama in the oath of office while keeping his Matt Sanderson photo the midst of his inaugural address. left hand over the Lincoln Bible “Drawn from every end of this Bethany Mongeau and her mother Barbara Barrows, both of Brooklyn, attended BY MATT SANDERSON earth; and because we have tasted the inauguration ceremony of President Barack Obama in Washington, D.C., VILLAGER STAFF WRITER Turn To INAUGURATION, A14 the bitter swill of Civil War and seg- page Tuesday, Jan. -

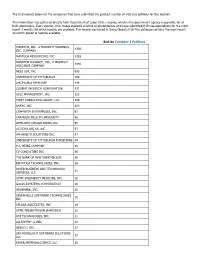

The H1B Records Below List the Companies That Have Submitted the Greatest Number of H1B Visa Petitions for This Location

The H1B records below list the companies that have submitted the greatest number of H1B visa petitions for this location. This information was gathered directly from Department of Labor (DOL) records, which is the government agency responsible for all H1B submissions. Every quarter, DOL makes available a listing of all companies who have submitted H1B visa applications for the most recent 3 months for which records are available. The records contained in Going Global's H1B Plus database contains the most recent 12-month period of records available. Sort by Company | Petitions MASTECH, INC., A MASTECH HOLDINGS, 4339 INC. COMPANY MASTECH RESOURCING, INC. 1393 MASTECH ALLIANCE, INC., A MASTECH 1040 HOLDINGS COMPANY NESS USA, INC. 693 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH 169 UHCP D/B/A UPMC MEP 144 COGENT INFOTECH CORPORATION 131 SDLC MANAGEMENT, INC. 123 FIRST CONSULTING GROUP, LLC 104 ANSYS, INC. 100 COMPUTER ENTERPRISES, INC. 97 CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY 96 INTELLECT DESIGN ARENA INC. 95 ACCION LABS US, INC. 63 HM HEALTH SOLUTIONS INC. 57 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH PHYSICIANS 44 H.J. HEINZ COMPANY 40 CV CONSULTING INC 36 THE BANK OF NEW YORK MELLON 36 INFOYUGA TECHNOLOGIES, INC. 36 BAYER BUSINESS AND TECHNOLOGY 31 SERVICES, LLC UPMC EMERGENCY MEDICINE, INC. 28 GALAX-ESYSTEMS CORPORATION 26 HIGHMARK, INC. 25 SEVEN HILLS SOFTWARE TECHNOLOGIES 25 INC VELAGA ASSOCIATES, INC 24 UPMC PRESBYTERIAN SHADYSIDE 22 DVI TECHNOLOGES, INC. 21 ALLEGHENY CLINIC 20 GENCO I. INC. 17 SRI MOONLIGHT SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 17 LLC BAYER MATERIALSCIENCE, LLC 16 BAYER HEALTHCARE PHARMACEUTICALS, 16 INC. VISVERO, INC. 16 CYBYTE, INC. 15 BOMBARDIER TRANSPORTATION 15 (HOLDINGS) USA, INC. -

United States of America First Circuit Court of Appeals

United States of America First Circuit Court of Appeals NO. 08-2300 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee, v. CIRINO GONZALEZ, Defendant/Appellant BRIEF OF DEFENDANT - APPELLANT By: Joshua L. Gordon, Esq. N.H. Bar No. 9046, Mass. Bar No. 566630 Law Office of Joshua L. Gordon 26 S. Main St., #175 Concord, NH 03301 (603) 226-4225 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES......................................... iii STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION....................................1 STATEMENT OF ISSUES...........................................2 STATEMENT OF FACTS AND STATEMENT OF THE CASE.............4 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT........................................6 ARGUMENT......................................................8 Convictions I. Mr. Gonzalez Was Convicted of Accessory and Conspiracy to Accessory, but not Conspiracy to Impede Officers..............8 A. Indictment.........................................8 B. Jury Instructions...................................11 C. Special Verdict....................................12 D. Sentencing for Dual-Object Conspiracy.................14 II. Mr. Gonzalez is Not Guilty of Count II Conspiracy............15 A. Government Did Not Prove All Elements of Conspiracy...15 B. Precedents Involving Conjunctive Indictments and Disjunctive Instructions Do Not Apply to Mr. Gonzalez’s Case...................................18 III. Count III Accessory after the Fact Indictment Failed to State an Element...............................................21 IV. No Evidence to Prove Mr. Gonzalez Knew the Elements of the Browns’ -

Download Our 2020 Corporate Profile

HIGHMARK HEALTH 2020 CORPORATE PROFILE 1 Living Health: Together for a Purpose 2020 Corporate Profile HIGHMARK HEALTH 2020 CORPORATE PROFILE 2 Our vision is a world Highmark Health is committed to reinventing the health experience so that everything and everyone works together for the health of those we serve. Boldly challenging unsustainable health care models of the past, we are where everyone building a new model, Living Health, to simplify the customer experience, free up clinicians to focus on care, embraces health. and leverage innovative technology and partnerships to deliver truly individualized health planning. We believe that creating a remarkable health experience will drive better health outcomes and lower total cost of care. Like our work, our financial priorities also serve our social purpose of building stronger communities of Our mission is to healthier people. In 2020, that included more than $750 million invested to support customers, providers, and create a remarkable communities during the pandemic, and another $760 million in capital investments. health experience, A DIVERSE PORTFOLIO OF LEADING HEALTH COMPANIES freeing people to Highmark Health’s diverse portfolio of aliates and subsidiaries meets a broad spectrum of health needs for be their best. consumers, business customers, and government entities. Highmark Inc. and its Blue-branded aliates HM Health Solutions combines technology and (Highmark Health Plans) proudly cover the leading industry knowledge to deliver business insurance needs of millions of individuals, families, solutions to health plan payers so they can run their and seniors, while also oering a variety of health- organizations eciently in a competitive and ever- related products and services. -

Historical and Clinical Study of Criminality with Special Reference to Theft, an Fred Brown

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 21 Article 7 Issue 3 November Fall 1930 Historical and Clinical Study of Criminality with Special Reference to Theft, An Fred Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Fred Brown, Historical and Clinical Study of Criminality with Special Reference to Theft, An, 21 Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 400 (1930-1931) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. AN HISTORICAL AND CLINICAL STUDY OF CRIMINALITY WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THEFT1 FRED BROWN TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. Introduction Chapter II. Theft and the Offender in Primitive Society. Chapter III. Crime and the Offender in Ancient Times Chapter IV. Theories of Crime in the Middle Ages Chapter V. Attitudes and Theories from the Beginning of the Eighteenth to the End of the Nineteenth Cen- tury Chapter VI. Contemporary Theories and -Studies of Crim- inality Bibliography AN HISTORICAL AND CLINICAL STUDY OF CRIMINALITY WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THEFT "Enemy" shall ye say but not "Villain," "Invalid" shall ye say but not "Wretch," "Fool" shall ye say but not "Sinner." "Hearken, ye judges! There is another madness besides, and it is before the deed. Ah! ye have not gone deep enough into this soul." -Thus Spake Zarathustra. -

2019 Highmark Health Annual Report: Corporate Profile

HIGHMARK HEALTH 2019 CORPORATE PROFILE 1 Embracing Health in Remarkable Ways GLORIA, AHN PATIENT ▶ 2019 Corporate Profile HIGHMARK HEALTH 2019 CORPORATE PROFILE 2 Our vision is a world Highmark Health is committed to reinventing the health experience so that everything and everyone works together seamlessly for the health of those we serve. Boldly challenging unsustainable health care models of where everyone the past, we are simplifying the customer experience, freeing up clinicians to focus on care, and leveraging embraces health. innovative technology and partnerships to deliver truly individualized health planning. We believe that creating a remarkable health experience is also the path to better health outcomes and lower total cost of care. Like our work, our organizational giving — totaling $206.5 million in 2019 — centers on our larger social purpose of Our mission is to building stronger communities of healthier people. create a remarkable A DIVERSE PORTFOLIO OF LEADING HEALTH CARE COMPANIES health experience, Highmark Health’s strong and diverse portfolio of businesses meets a broad spectrum of health needs for freeing people to consumers, business customers, and government entities. be their best. Highmark Inc. and its Blue-branded affiliates (Health HM Home & Community Services specializes Plan) proudly cover the insurance needs of millions of in population health management solutions that individuals, families and seniors, while also offering a benefit payers, providers, and customers. variety of health-related products and services. HM Insurance Group works to protect businesses Allegheny Health Network (AHN) has more and their employees from the financial risks than 250 clinical facilities, including hospitals associated with catastrophic health care costs. -

Highmark Inc. Company Overview

Highmark Inc. Company Overview Vision A world where everyone embraces health Mission To create a remarkable health experience, freeing people to be their best Key Statistics • Founded Mid 1930s • Number of employees 6,000 • 5.6 million members are covered by Highmark Inc. • Highmark Health had $18 Billion in Operating Revenue in 2019 • Highmark Inc., together with its Blue-branded affiliates, collectively comprise the fourth-largest overall Blue Cross Blue Shield-affiliated organization in the country based on membership. Company Headquarters • Pittsburgh, Pa. Community Support • In 2019, the Health Plans' corporate giving benefited hundreds of organizations, donating more than $17 million in the areas of western, central, and northeastern Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Delaware. In addition, Highmark's signature program, Walk for a Healthy Community, along with Adopt-a-School programs initiated by employees in Pittsburgh and Erie, and National Make a Difference Day of volunteering, provided significant benefits to individuals and the communities the Health Plans proudly serve. 1 Products • Highmark Inc. is a national, diversified health care partner based in Pittsburgh that serves members across the United States through its businesses in health insurance, dental insurance, and reinsurance. We offer a variety of plans in our core service areas. • Our diversified businesses also provide a broad spectrum of specialty products, such as dental insurance, and reinsurance to 50 million Americans across all 50 states and the District of Columbia. • Our diversified businesses rank among the nation's leaders in their categories: o Fifth largest dental insurance carrier in the U.S. o Among the top five largest stop loss carriers Awards • Medicare Advantage plans recognized for member satisfaction For the fourth consecutive year, Highmark's Medicare Advantage plans received high rankings in the annual J.D. -

Town of St. Joseph

TOWN OF ST. JOSEPH INVESTIGATIVE AUDIT ISSUED MARCH 1, 2016 LOUISIANA LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR 1600 NORTH THIRD STREET POST OFFICE BOX 94397 BATON ROUGE, LOUISIANA 70804-9397 LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR DARYL G. PURPERA, CPA, CFE DIRECTOR OF INVESTIGATIVE AUDIT ROGER W. HARRIS, J.D., CCEP Under the provisions of state law, this report is a public document. A copy of this report has been submitted to the Governor, to the Attorney General, and to other public officials as required by state law. A copy of this report is available for public inspection at the Baton Rouge office of the Louisiana Legislative Auditor and at the office of the parish clerk of court. This document is produced by the Louisiana Legislative Auditor, State of Louisiana, Post Office Box 94397, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70804-9397 in accordance with Louisiana Revised Statute 24:513. Eight copies of this public document were produced at an approximate cost of $31.20. This material was produced in accordance with the standards for state agencies established pursuant to R.S. 43:31. This report is available on the Legislative Auditor’s website at www.lla.la.gov. When contacting the office, you may refer to Agency ID No. 2321 or Report ID No. 50140032 for additional information. In compliance with the Americans With Disabilities Act, if you need special assistance relative to this document, or any documents of the Legislative Auditor, please contact Elizabeth Coxe, Chief Administrative Officer, at 225-339-3800. LOUISIANA LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR DARYL G. PURPERA, CPA, CFE March 1, 2016 THE HONORABLE EDWARD BROWN, MAYOR, AND MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF ALDERMEN TOWN OF ST. -

United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit

Case: 10-1081 Document: 00116320473 Page: 1 Date Filed: 01/19/2012 Entry ID: 5611724 United States Court of Appeals For the First Circuit No. 09-2402 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee, v. ELAINE BROWN, Defendant, Appellant, No. 10-1081 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee, v. EDWARD BROWN, Defendant, Appellant. APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW HAMPSHIRE [Hon. George Z. Singal, U.S. District Judge] Before Lynch, Chief Judge, Lipez and Thompson, Circuit Judges. Case: 10-1081 Document: 00116320473 Page: 2 Date Filed: 01/19/2012 Entry ID: 5611724 Leslie Feldman-Rumpler for appellant Elaine Brown. Dean Stowers, with whom Stowers Law Firm was on brief, for appellant Edward Brown. Seth R. Aframe, Assistant United States Attorney, with whom John P. Kacavas, United States Attorney was on brief, for appellee. January 19, 2012 Case: 10-1081 Document: 00116320473 Page: 3 Date Filed: 01/19/2012 Entry ID: 5611724 THOMPSON, Circuit Judge. A nine-month long stand-off between United States Marshals (the "Marshals") and husband and wife team, Edward and Elaine Brown, resulted in the Browns' criminal convictions. Edward and Elaine1 each appealed and we consolidated. Both claim that the district court committed a myriad of errors justifying reversal. After careful consideration, we reject each argument and affirm. BACKGROUND2 A. The Tax Evasion Trial To put this appeal in context, we begin with another criminal matter involving the Browns. In April 2006, Edward and Elaine were indicted by a federal grand jury on charges relating to their failure to pay federal income tax - an omission that stemmed from the Browns' belief that they were not legally obligated to do so.