In Re Victor Romm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2002 Opinions

ERIE COUNTY LEGAL JOURNAL (Published by the Committee on Publications of the Erie County Legal Journal and the Erie County Bar Association) Reports of Cases Decided in the Several Courts of Erie County for the Year 2002 LXXXV ERIE, PA JUDGES of the Courts of Erie County during the period covered by this volume of reports COURTS OF COMMON PLEAS HONORABLE WILLIAM R. CUNNINGHAM -------- President Judge HONORABLE GEORGE LEVIN ---------------------------- Senior Judge HONORABLE ROGER M. FISCHER ----------------------- Senior Judge HONORABLE FRED P. ANTHONY --------------------------------- Judge HONORABLE SHAD A. CONNELLY ------------------------------- Judge HONORABLE JOHN A. BOZZA ------------------------------------ Judge HONORABLE STEPHANIE DOMITROVICH --------------------- Judge HONORABLE ERNEST J. DISANTIS, JR. ------------------------- Judge HONORABLE MICHAEL E. DUNLAVEY -------------------------- Judge HONORABLE ELIZABETH K. KELLY ----------------------------- Judge HONORABLE JOHN J. TRUCILLA --------------------------------- Judge Volume 85 TABLE OF CASES -A- Ager, et al. v. Steris Corporation ------------------------------------------------ 54 Alessi, et al. v. Millcreek Township Zoning Hearing Bd. and Sheetz, et al. 77 Altadonna; Commonwealth v. --------------------------------------------------- 90 American Manufacturers Mutual Insurance Co.; Odom v. ----------------- 232 Azzarello; Washam v. ------------------------------------------------------------ 181 -B- Beaton, et. al.; Brown v. ------------------------------------------------------------ -

Two Locals Perish in Car Crash

Mailed free to requesting homes in Eastford, Pomfret & Woodstock Vol. IV, No. 19 Complimentary to homes by request (860) 928-1818/e-mail: [email protected] ‘Courage is the price that life exacts for granting peace.’ FRIDAY, JANUARY 23, 2009 Two Quiet Corner observes historic inauguration day locals OBAMA SWORN IS AS 44TH U.S. PRESIDENT BY MATT SANDERSON regation, and emerged from that VILLAGER STAFF WRITER dark chapter stronger and united, Barack Obama was sworn in as we cannot help but believe that the perish in the 44th president of the United old hatreds shall someday pass; that States Tuesday, Jan. 20, at the presi- the lines of tribe shall soon dis- dential inauguration, and has solve. …” moved into his new residence with It was estimated that more than car crash his family at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. two million people crowded the in Washington, D.C. He is the first National Mall and the parade route U.S. president of African-American along Pennsylvania Avenue just to AREA’S FIRST descent. be a part of the occasion. “… We are shaped by every lan- After being sworn in and reciting FATALITIES IN 2009 guage and culture,” said Obama in the oath of office while keeping his Matt Sanderson photo the midst of his inaugural address. left hand over the Lincoln Bible “Drawn from every end of this Bethany Mongeau and her mother Barbara Barrows, both of Brooklyn, attended BY MATT SANDERSON earth; and because we have tasted the inauguration ceremony of President Barack Obama in Washington, D.C., VILLAGER STAFF WRITER Turn To INAUGURATION, A14 the bitter swill of Civil War and seg- page Tuesday, Jan. -

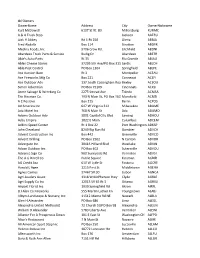

Owner Info with Codes.Pdf

tbl Owners OwnerName Address City OwnerNickname Kurt McDowell 6107 St Rt. 83 Millersburg KURMC A & A Truck Stop Jackson AATRU Jack H Abbey Rd 1 Rt 250 Olena ABBJA Fred Abdalla Box 114 Stratton ABDFR Medina Foods, Inc 9706 Crow Rd. Litchfield ABDNI Aberdeen Truck Parts & Service Budig Dr Aberdeen ABETR Abie's Auto Parts Rt 35 Rio Grande ABIAU Ables Cheese Stores 37295 5th Ave/PO Box 311 Sardis ABLCH Able Pest Control PO Box 1304 Springfield ABLPE Ace Auction Barn Rt 3 Montpelier ACEAU Ace Fireworks Mfg Co Box 221 Conneaut ACEFI Ace Outdoor Adv 137 South Cassingham RoadBexley ACEOU Simon Ackerman PO Box 75109 Cincinnati ACKSI Acme Salvage & Wrecking Co 2275 Smead Ave Toledo ACMSA The Bissman Co. 193 N Main St, PO Box 1628Mansfield ACMSI A C Positive Box 125 Berlin ACPOS Ad America Inc 647 W Virginia 312 Milwaukee ADAME Ada Motel Inc 768 N Main St Ada ADAMO Adams Outdoor Adv 3801 Capital City Blvd Lansing ADAOU Adco Empire 1822 E Main Columbus ADCEM Adkins Speed Center Rt 1 Box 22 Port Washington ADKSP John Cleveland 8249 Big Run Rd Gambier ADVCH Advent Construction Inc Box 442 Greenville ADVCO Advent Drilling PO Box 2562 N Canton ADVDR Advergate Inc 30415 Hilliard Blvd Westlake ADVIN Advan Outdoor Inc PO Box 402 Sutersville ADVOU Advance Sign Co 900 Sunnyside Rd Vermilion ADVSI The A G Birrell Co Public Square Kinsman AGBIR AG Credit Aca 610 W Lytle St Fostoria AGCRE Harold L Agee 1215 First St Middletown AGEHA Agnes Carnes 37467 SR 30 Lisbon AGNCA Agri-Leaders Assoc 1318 W McPherson Hwy Clyde AGRLE Agri Supply Co Inc 12015 SR 65 Rt 3 Ottawa -

Calls (This Was Old Days) Were to Secretaries/Pas Of

Excellence. NO EXCUSES! 68 Ways to Launch Your Journey. NOW. Tom Peters 27 March 2014 1 To John Hetrick Inventor of the auto air bag, 1952 2 This plea for Excellence is a product of Twitter, where I hang out. A lot. Usually, my practice is a comment here and a comment there—driven by ire or whimsy or something I’ve read or observed. But a while back—and for a while—I adopted the habit of going off on a subject for a semi-extended period of time. Many rejoinders and amendments and (oft brilliant) extensions were added by colleagues from all over the globe. So far, some 68 “tweetstreams” (or their equivalent from some related environments) have passed (my) muster—and are included herein. There is a lot of bold type and a lot of RED ink and a lot of (red) exclamation marks (!) in what follows. First, because I believe this is important stuff. And second, because I am certain there are no excuses for not cherrypicking one or two items for your T.T.D.N. list. (Things To Do NOW.) Excellence. No Excuses. Now. 3 Epigraph: The ACCELERATING Rate of Change “The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function.”—Albert A. Bartlett* *from Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, The Second Machine Age, “Moore’s Law and the Second Half of the Chessboard”/“Change” is not the issue—change has always been with us. But “this time” may truly be different. The ACCELERATION of change is unprecedented—hence, the time for requisite action is severely compressed. -

Competition Makes Minority Enrollment Small

(£mmtrttntt iaUu GJamptta Vol. LXXVI NO. 8 The University of Connecticut Friday, September 16,1982 j Competition makes minority enrollment small by Liz Hayes Staff Writer few minorities in the state to because there are so few dents to UConn. "It's our goal place more restrictions on to better the situation for the In 1981, the 913 minority begin with, this added com- minority students here to girls than boys. Boys are en- students enrolled at UConn petition makes it more dif- begin with. fall of 1981," Wiggins said. couraged to play football. made up 5.8% of the entire ficult for UConn to enroll the Carol Wiggins, Vice Presi- While the disparity between Girls spend more time study- student body, but state fig- numbers of minorities they dent of Student Affairs and minority and non-minority en- ing and learn to organize their ures show that minorities ac- would like to. Services, said that she was rollment is great, the ratio of time much better." he said. count for 9.9% of Connecticut's Williams said that the main "concerned that there seems male to female students at Vlandis said that he felt total population. reason minorities choose to be such a small percentage UConn is nearly 50:50, accord- those students who knew The reason for this dis- other universities over UConn of minority students at the ing to the 1982-83 University how to organize their time crepancy, according to Larry is because UConn doesn't university. We are very active- of Connecticut Bulletin. well were able to get higher Williams, Assistant Direc tor of offer the financial aid and ly trying to do something The Bulletin's registration grades than those students Admissions at UConn. -

Cowen Research Themes

COWEN RESEARCH THEMES EDGE COMPUTING2021 & 5G MOBILITY TECHNOLOGY ESG & ENERGY TRANSITION ROBOTICS & AUTOMATION NEW PARADIGMS IN COMPUTING CONSUMER TRANSFORMATION CANNABIS LIQUID BIOPSY TARGETED THERAPIES CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM ELECTION 2020 U.S. / CHINA COMPETITION & DECOUPLING BIG TECH & GOVERNMENT EQUITY & FAIRNESS COWEN TABLE.COM/THEMES2021 OF CONTENTS COWENCOWEN.COM/THEMES2021RESEARCH FROM COWEN DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH ROBERT FAGIN COVID-19 forced a year of “creative destruction,” wherein businesses rushed to challenge conventional models and adapt to new norms. In many cases, such as with e-commerce and telehealth, a multi-year march toward adoption was dramatically accelerated by a stay-at-home and work-from-home environment. Simultaneously, a politically and socially charged atmosphere, including a contentious U.S. election and deepening geopolitical rifts such as United States- China relations, further increased market tension and uncertainty. Remarkably, despite this backdrop of general unease and disorder, extraordinary innovation persisted in areas as diverse as targeted medical therapies, edge computing, 5G, robotics and automation, electrified transportation, and the adoption of clean energy. In this Handbook, we once again feature themes where Cowen’s domain expertise has been central to the discussion and debate. In nearly all cases, Cowen Research EDGE COMPUTING & 5G PAGE 4 | VIDEO PODCAST offered its hallmark collaborative approach to help inform our viewpoints, working MOBILITY TECHNOLOGY PAGE 10 | VIDEO PODCAST across sector teams to provide valuable perspective, and incorporating the views of our Washington Research Group in a rapidly shifting political environment. Each ESG & ENERGY TRANSITION PAGE 16 | VIDEO PODCAST theme highlighted is accompanied by a listing of relevant Cowen reports and events, which we hope supports deeper engagement on these pivotal issues. -

Fiscal Report | 1 You Can Start Something Big

Start Something FISCAL2016 REPORT to the community 2016 BBBSPGH Fiscal Report | 1 You Can Start Something Big Meetings that sometimes begin with awkward introductions same time, we are dedicated to being responsible stewards of and hesitant conversations turn into friendships that last for agency resources. years. In 2015, we served a record 1,400 children from across the Imagine Big Brother Matt on his way to meet his Little Brother Pittsburgh area and we are on target to reach an additional Xavier. Matt is nervous and hopes Xavier will like him. Xavier is 100 children in 2016. Despite our progress, the demand for our just as excited to finally meet his Big Brother. He was told that services exceeds our capacity, with a waiting list of more than Matt loves basketball and Star Wars—what could be better than 300 children seeking mentors. Your support throughout the year that? enables us to expand our services to reach more kids in need, Xavier’s mom, Teresa, was silently hoping Matt would be without compromising our superior quality. the mentor her 8-year-old son has needed for so long. She has Whether it is finding the perfect match between a Big and been doing a great job raising Xavier, but he recently started to Little, creating a custom partnership package for a corporation, experience difficulties in school. Xavier never met his biological or developing a special match activity to engage our mentors father and has no consistent male role model in his life. Teresa and mentees, we work to create results that benefit our made the decision to call Big Brothers Big Sisters of Greater children, families, volunteers, and supporters—and in turn, our Pittsburgh to begin the journey. -

Local Board Hearing Information September 2020 Updated 9/29/20 10:01AM

Local Board Hearing Information September 2020 Updated 9/29/20 10:01AM Adams hearing #1 Adams County Service Complex, Conference room, Room 125 - Decatur 09/22/2020 9:00 am AZAR INCORPORATED RR0107689 Beer Wine & Liquor - Restaurant (210) Renewal DBA: BACK 40 JUNCTION 1011 N. 13TH STREET Decatur IN 46733 Conrad Family Restaurant LLC RR0136774 Beer Wine & Liquor - Restaurant (210) New Application DBA: Two Brothers Bar & Restaurant 239 West Monroe Street Decatur IN 46733 KROGER LIMITED PARTNERSHIP I DL0118800 Beer Wine & Liquor - Drug Store Renewal DBA: KROGER J-407 929 S. 13TH ST. Decatur IN 46733 Small Town Vapes LLC RR0133401 Beer Wine & Liquor - Restaurant (210-1) Renewal DBA: SMALL TOWN VAP AND BREW 116 W MONROE ST Decatur IN 46733 V F W 6751 RC0112872 Beer Wine & Liquor - Fraternal Club Renewal DBA: V.F.W. POST #6751 740 E. LINE ST. Geneva IN 46740 Allen hearing #1 Citizens Square 200 E. Berry, Garden Level, Community Rm.030 - Fort Wayne 09/14/2020 9:30 am 123, INC. RR0212646 Beer Wine & Liquor - Restaurant (210) Renewal DBA: CEBOLLA'S 5930 W. JEFFERSON BLVD. SUITE B Fort Wayne IN 46804- A DAY AWAY SALON AND SPA, INC. RR0234348 Beer & Wine Retailer - Restaurant Renewal DBA: 487 E DUPONT RD Fort Wayne IN 46825 AGAVES INC RR0283364 Beer Wine & Liquor - Restaurant (210) Renewal DBA: AGAVES 212 E WASHINGTON CENTER RD Fort Wayne IN 46825- AHTRST Concessions, LLC RH0230137 Beer Wine & Liquor - Hotel Renewal DBA: HILTON GARDEN INN/ HOMEWOOD SUITES 8615-8621 US Highway 24 Fort Wayne IN 46804 Aladdin Food Management Services LLC CH0230091 Beer Wine & Liquor - Catering Hall New Application DBA: Aladdin Food Management Services, LLC 2101 E Coliseum Blvd. -

Community Report

Community Report 2015.16 COMMUNITY REPORT | 2015.16 A LETTER FROM THE PITTSBURGH PENGUINS CEO & PRESIDENT The Pittsburgh Penguins are more than a hockey team. We are proud members of our community – from our players and coaches to our executives and office staff – and we believe we have a responsibility to use the unique platform of professional sports to make a deep and lasting impact on our city and our region. It goes far beyond the $6.1 million that the Pittsburgh Penguins Foundation contributed to charitable and community causes during the 2015-16 season (athough we are very proud of that!). It involves such wide-ranging efforts as delivering tablets to local schools through our signature Tablets in Education program; providing free baseline concussion testing to young athletes since 2011 through the HEADS UP initiative; building 12 dek hockey rinks in the Pittsburgh region; awarding annual scholarships to deserving high school seniors; and holding unique charity events such as the Aces & Ice Casino Night and the ROOT Sports Charity Night. Our players contribute in so many ways – many in private, out of the spotlight – but some of their more public ventures include visiting Children’s Hospital each season and personally delivering tickets to the homes and businesses of our season ticket holders. Co-owners Mario Lemieux and Ron Burkle have instilled a long-lasting commitment to community outreach and fan interaction through all levels of the Penguins organization. We are proud to serve the citizens of the Pittsburgh region – and especially the young people who are building such a strong foundation for a very bright future. -

Impact Report Impact © Photo by Nancy Andrews

© Photo by Nancy Andrews © Photo REPORT PERIOD 2018 Impact Report Innovation to Impact We believe good food belongs to people, not landfills. Table of Contents A Primer on Food Surplus, Food Insecurity and Environmental Sustainability 4 Why We Need to Innovate to Serve People 16 People-Powered Technology 20 Our Impact 22 Rapid Response 32 Strategic Projects 34 Awards 41 Food Donors 42 Nonprofit Partners 46 Food Rescue Heroes 50 Financials 54 Financial Donors 55 Staff, Board, and Advisory Board 58 From the CEO This February, I was invited to deliver the keynote at the Pennsylvania Association of Sustainable Agriculture (PASA) Conference. As I prepared to go up the stage, I was unexpectedly overcome with emotion – seeing 300 farmers, the women and men who work hard to grow our food. I have worked at a small farm, and if you have done so or even have grown an edible garden in your yard, you KNOW the extraordinarily hard work required. And as I prepared to say the words, “40% of food goes to waste,” I could only think I am really saying to them “half of all your labor, we will throw in the garbage.” I have so much love and respect for our farmers. Throwing away perfectly good food devalues our farmers and all the resources that go into producing food. I feel the same on the other end, when I have the privilege of visiting one of our nonprofit partners or reading letters and emails from people whom we have delivered food to. They begin with “I am homebound...” “I have three kids and no car….” “I did not know how I was going to make it til the end of the month….” “We make too much to qualify for benefits but we cannot make ends meet.” And they end with, “this made a big difference.” Throwing away perfectly good food is Food Injustice. -

What to Do in the Clarion Area ...In 4 Hours Or Less

Clarion Area Chamber of Business & Industry STD PRSRT 21 North 6th Avenue US POSTAGE PAID Clarion, PA 16214 PERMIT No. 20 CLARION, PA 16214 The Clarionto do Area business Chamber with encouragesother Chamber Chamber members members ...in 4hours orless What to Do inthe Clarion Area Clarion Services API Autobody Products Cater Mama Gatesman Auto Body Carstar Table of Contents 1108 East Main Street P.O. Box 213 28177 Route 66 Clarion, PA 16214 Clarion, PA 16214 Lucinda, PA 16235 814-226-4460 814-297-8085 814-226-9468 Quick Glance at the Area……..………………………………..……………………..3 ATM - Clarion Co. Com. Bank Central Garage 592 Main Street 738 South Street Rear IDA Wholesale Clarion, PA 16214 Clarion, PA 16214 44 Circle Drive Attractions………………………………………………..……………….…….. …….3 ATM - Clarion Federal Credit Union 814-226-7160 Shippenville, PA 16254 144 Holiday Inn Rd. 814-226-5493 Clarion Animal Hospital Events…………………………………………………………………...……….……..4 Clarion, PA 16214 22904 Route 68 Jeff’s Performance Plus, Inc. ATM - Clarion Mall Clarion, PA 16214 10760 Rt 322 Summer Festivals, Fairs and Other Events…………….……..…………..4 22631 Route 68 814-227-2603 Shippenville, PA 16254 Clarion, PA 16214 814-226-6900 Clarion Beverage Fall Festivals and Attractions…….……………………...…………….……5 ATM - Community First Bank 9 North Fourth Ave. 601 Main Street Clarion, PA 16214 Knox Fitness LLC Holiday Events………………………….……………………….…………...5 Clarion, PA 16214 814-226-7031 436 E Penn Ave Knox, PA 16232 ATM - Eagle Commons Clarion County Airport 814-797-5975 Places to See………….…………………………………………..………………...…6 Clarion University 395 Airport Road Clarion, PA 16214 Shippenville, PA 16254 Liberty Street Church of God Fitness & Athletics…………………………………………..………………………...8 ATM - Eat’n Park 814-226-9993 240 Liberty Street Route 68 & Perkins Road Clarion, PA 16214 Clarion County Farmers Market Museums, Galleries, & Theatres…………….………………………..……………..8 Clarion, PA 16214 814-226-8672 1889 Brook Rd. -

NASDAQ DUCK 2002.Pdf

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) (X) ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended February 3, 2002 OR ( ) TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from _____________ to ___________ Commission File Number 0-20269 DUCKWALL-ALCO STORES, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Kansas 48-0201080 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 401 Cottage Street Abilene, Kansas 67410-2832 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant's telephone number including area code: (785) 263-3350 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: NONE Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Common Stock, par value $.0001 per share (Title of Class) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes X No _____ Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of registrant's know definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K.