Botanist Interior 42.3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toronto Master Gardeners Ask Plant Id Questions

TORONTO MASTER GARDENERS ASK PLANT ID QUESTIONS Image Question Answer Growing in ditches beside a gravel road It is challenging to identify a plant from a single leaf, and I consulted our team in Township of Perry 25 minutes north of Master Gardeners, several of whom feel that the plant is likely some sort of Huntsville. Cant find it in any of our of dock. Consider the following: reference books. Leaves are emerging from ground singly and veins are deep ñ Rumex sanguineus var.sanguineus (red-veined or bloody red. dock). See the Missouri Botanical Garden monograph ñ Rumex obtusifolius (broadleaved dock/ bitter dock). See Illinois Wildflowers – Bitter Dock ñ Rumex aquaticus (Scottish dock). See Nature Gate’s Scottish Dock Another suggestion was this might be pokeweed (Phytolacca Americana). See Ohio State University’s Ohio Perennial and Biennial Weed May 2019 Guide – Common PokeweedClick on the above links and you'll see photos that show that these plants have leaves that resemble those of your mystery plant, in many respects. However, with docks and the common pokeweed, leaves generally emerge from the same clump, not singly. As well, these plants have lance-shaped leaves, which seem to differ quite a bit from the oblong-shaped leaf of shown in the photo you submitted.Finally, it is possible that the plant is related to dock, but is a sorrel (Rumex acetosa) - some sorrels have leaves that are shaped more like the leaf in your photo. For example, see Nature Gate's Common sorrel My neighbour gave me this plant, that I Your neighbour gave you a Bergenia cordifolia, commonly called Bergenia or planted las year. -

The Relation Between Road Crack Vegetation and Plant Biodiversity in Urban Landscape

Int. J. of GEOMATE, June, 2014, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Sl. No. 12), pp. 885-891 Geotech., Const. Mat. & Env., ISSN:2186-2982(P), 2186-2990(O), Japan THE RELATION BETWEEN ROAD CRACK VEGETATION AND PLANT BIODIVERSITY IN URBAN LANDSCAPE Taizo Uchida1, JunHuan Xue1,2, Daisuke Hayasaka3, Teruo Arase4, William T. Haller5 and Lyn A. Gettys5 1Faculty of Engineering, Kyushu Sangyo University, Japan; 2Suzhou Polytechnic Institute of Agriculture, China; 3Faculty of Agriculture, Kinki University, Japan; 4Faculty of Agriculture, Shinshu University, Japan; 5Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants, University of Florida, USA ABSTRACT: The objective of this study is to collect basic information on vegetation in road crack, especially in curbside crack of road, for evaluating plant biodiversity in urban landscape. A curbside crack in this study was defined as a linear space (under 20 mm in width) between the asphalt pavement and curbstone. The species composition of plants invading curbside cracks was surveyed in 38 plots along the serial National Route, over a total length of 36.5 km, in Fukuoka City in southern Japan. In total, 113 species including native plants (83 species, 73.5%), perennial herbs (57 species, 50.4%) and woody plants (13 species, 11.5%) were recorded in curbside cracks. Buried seeds were also obtained from soil in curbside cracks, which means the cracks would possess a potential as seed bank. Incidentally, no significant differences were found in the vegetation characteristics of curbside cracks among land-use types (Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test, P > 0.05). From these results, curbside cracks would be likely to play an important role in offering habitat for plants in urban area. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Patterns of Resource Allocation in Different Habitats of Kalimeris Intergrifolia in Northeast China Z

Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agraria y Alimentaria (INIA) Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2011 9(4), 1224-1232 Available online at www.inia.es/sjar ISSN: 1695-971-X doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5424/sjar/20110904-162-11 eISSN: 2171-9292 Patterns of resource allocation in different habitats of Kalimeris intergrifolia in Northeast China Z. N. Yuan1,2, J. M. Lu1*, J. Y. Chen1 and S. Z. Jiang2 1College of Life Sciences, Northeast Normal University. Changchun 130024. P. R. China 2 Key Laboratory of Molecular Cytogenetics and Genetic Breeding of Heilongjiang Province; College of life Sciences and Technology, Harbin Normal University. Harbin 150025. P. R. China Abstract Understanding parameters that drive plant resource allocation for reproduction in potentially economically and environ- mentally important species, such as Kalimeris intergrifolia, is essential to maximize production rates. Hence, this study evaluates the characteristics in reproductive resource allocation of two K. intergrifolia communities at a saline-alkali open meadow and at a semi-enclosed secondary broad-leaved forest fringe, in the Songnen plains region of northeast China. Ramets from each habitat type were sampled at three intervals during the ripening stage (June-October). Relative resource distribution was quantified by measuring the dry weight of the above-ground ramet components, including the stem, leaf, corymb and seeds. The results indicated high variability in the distribution of resource allocation for both types, with larger phenotypic plasticity being recorded for the forest fringe than the open meadow. However, the allocation of re- sources into reproductive organs was higher in the open meadow than in the forest fringe, demonstrating that the open community was advantageous to the reproduction. -

Sequencing and Analysis of Chrysanthemum Carinatum Schousb and Kalimeris Indica

molecules Article Sequencing and Analysis of Chrysanthemum carinatum Schousb and Kalimeris indica. The Complete Chloroplast Genomes Reveal Two Inversions and rbcL as Barcoding of the Vegetable Xia Liu * ID , Boyang Zhou, Hongyuan Yang, Yuan Li, Qian Yang, Yuzhuo Lu and Yu Gao State Key Laboratory of Food Nutrition and Safety, Key Laboratory of Food Nutrition and Safety, Ministry of Education of China, College of Food Engineering and Biotechnology, Tianjin University of Science &Technology, Tianjin 300457, China; [email protected] (B.Z.); [email protected] (H.Y.); [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (Q.Y.); [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (Y.G.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-022-6091-2406 Received: 20 April 2018; Accepted: 31 May 2018; Published: 5 June 2018 Abstract: Chrysanthemum carinatum Schousb and Kalimeris indica are widely distributed edible vegetables and the sources of the Chinese medicine Asteraceae. The complete chloroplast (cp) genome of Asteraceae usually occurs in the inversions of two regions. Hence, the cp genome sequences and structures of Asteraceae species are crucial for the cp genome genetic diversity and evolutionary studies. Hence, in this paper, we have sequenced and analyzed for the first time the cp genome size of C. carinatum Schousb and K. indica, which are 149,752 bp and 152,885 bp, with a pair of inverted repeats (IRs) (24,523 bp and 25,003) separated by a large single copy (LSC) region (82,290 bp and 84,610) and a small single copy (SSC) region (18,416 bp and 18,269), respectively. In total, 79 protein-coding genes, 30 distinct transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, four distinct rRNA genes and two pseudogenes were found not only in C. -

2021 Online Plant Discovery Day Woody Plant List (Based on Availability, Subject to Change

2021 Online Plant Discovery Day Woody Plant List (Based on availability, subject to change. Rev. 4/1/21) Botanical Name Common Name Acer circinatum Vine Maple Acer griseum Paperbark Maple Aesculus pavia Red Buckeye Amelanchier canadensis Serviceberry Aronia arbutifolia 'Brilliantissima' Red Chokeberry Buddlea x 'SMNBDW' Pugster White® Butterfly Bush Buddlea x 'SMNBDD' Lo & Behold Ruby Chip™ Butterfly Bush Callicarpa x 'NCCX2' PEARL GLAM® Beautyberry Calycanthus floridus Sweetshrub Calycanthus x 'Venus' Carolina Allspice Carex glauca Blue Sedge Carpinus caroliniana Wisconsin Red™ 'My Select Strain' Wisconsin Red™ Musclewood Carpinus cordata Bigleaf Hornbeam Carpinus japonica Japanese Hornbeam Caryopteris x clandonesis 'CT-9-12' Beyond Midnight® Bluebeard Cephalotaxus harringtonia 'Duke Gardens' Japanese Plum Yew Cercis canadensis 'Black Pearl'™ 'JN-16' Black Pearl Redbud Cercis canadensis var. texensis 'Oklahoma' Texas Redbud Cercis canadensis var. texensis 'Pink Pom Poms' Texas Redbud Cercis chinensis 'Don Egolf' Chinese Redbud Chamaecyparis lawsoniana 'SMNCLGTB' Pinpoint® Blue False Cypress Chamaecyparis pisifera 'Dow Whiting' Soft Serve® False Cypress Chionathus virginicus Fringetree Clematis heracleifolia Clematis Clethra alnifolia 'Hummingbird' Hummingbird Summersweet Comptonia peregrina Sweet Fern Cornus controversa 'Janine' Janine Giant Pagoda Dogwood Cornus kousa 'KN30-8' Rosy Teacups® Dogwood Cornus kousa 'Scarlet Fire' Scarlet Fire Dogwood Cornus kousa 'Summer Gold' Summer Gold Chinese Dogwood Cornus kousa var. chinensis Chinese Dogwood Cornus sericea 'Budd's Yellow' Yellowtwig Dogwood Cotinus coggygria 'MINCOJAU3' Winecraft Gold® Smokebush Cotinus coggygria 'NCC01' Winecraft Black® Smokebush Corylus avellana 'Burgundy Lace' Burgundy Lace Filbert Cryptomeria japonica 'Globosa Nana' Dwarf Japanese Cedar Cytisus scoparius 'SMNCSAB' SISTER REDHEAD® Scotch Broom Ficus carica 'Brown Turkey' Brown Turkey Fig Ficus carica 'Chicago Hardy' Chicago Hardy Fig Fothergilla 'Mt. -

Deer Management in the Garden

DEER MANAGEMENT IN THE GARDEN Deer can be a nuisance at times to gardeners in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area. As development alters habitats and eliminates predators, deer have adapted to suburban life and their population has grown, increasing the demand and competition for food. In some areas, landscape plants have become one of their food sources. When food is limited, deer may eat plants they normally don’t touch to satisfy their hunger. Although no plant is deer proof, you can make your garden less inviting to wildlife. Below are several strategies, including a list of plants that have been shown that deer dislike in order to discourage these uninvited guests. Deer will continue to adapt to their changing environment, and you’ll need to continue trying different control strategies. But with just a little planning, you can have a beautiful garden and co-exist with deer. METHODS OF DEER MANAGEMENT EXCLUSION: A physical barrier is the most effective method to keep deer from foraging. A 7’ tall fence is required to be effective. Deer fencing should be within easy view of the deer and should lean out towards the deer, away from your garden. A fine mesh is used for the black plastic fencing, which does not detract from the beauty of your landscape. If fencing is not practical, drape deer netting over vulnerable plants. Anchor or fasten deer netting to the ground to prevent the deer from pulling it off of the plants. REPELLENTS: Deer repellents work either through taste, scent, or a combination of both. -

C14 Asters.Sym-Xan

COMPOSITAE PART FOUR Symphyotrichum to Xanthium Revised 1 April 2015 SUNFLOWER FAMILY 4 COMPOSITAE Symphyotrichum Vernonia Tetraneuris Xanthium Verbesina Notes SYMPHYOTRICHUM Nees 1833 AMERICAN ASTER Symphyotrichum New Latin, from Greek symphysis, junction, & trichos, hair, referring to a perceived basal connation of bristles in the European cultivar used by Nees as the type, or from Greek symphyton, neuter of symphytos, grown together. A genus of approximately Copyrighted Draught 80 spp of the Americas & eastern Asia, with the greatest diversity in the southeastern USA (according to one source). Cook Co, Illinois has 24 spp, the highest spp concentration in the country. See also Aster, Eurybia, Doellingeria, Oclemena, & Ionactis. X = 8, 7, 5, 13, 18, & 21. Density gradient of native spp for Symphyotrichum within the US (data 2011). Darkest green (24 spp. Cook Co, IL) indicates the highest spp concentration. ©BONAP Symphyotrichum X amethystinum (Nuttall) Nesom AMETHYST ASTER, Habitat: Mesic prairie. Usually found close to the parents. distribution - range: Culture: Description: Comments: status: phenology: Blooms 9-10. “This is an attractive aster with many heads of blue or purple rays; rarer white and pink-rayed forms also occur. … Disk flowers are perfect and fertile; ray flowers are pistillate and fertile.” (ILPIN) VHFS: Formerly Aster X amethystinus Nutt. Hybrid between S novae-angliae & S ericoides. This is a possible hybrid of Aster novae-angliae and Aster ericoides, or of A. novae-angliae and A. praealtus” (Ilpin) Symphyotrichum X amethystinum Symphyotrichum anomalum (Engelmann) GL Nesom BLUE ASTER, aka LIMESTONE HEART-LEAF ASTER, MANY RAY ASTER, MANYRAY ASTER, MANY-RAYED ASTER, subgenus Symphyotrichum Section Cordifolii Copyrighted Draught Habitat: Dry woods. -

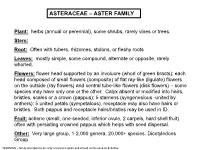

Asteraceae – Aster Family

ASTERACEAE – ASTER FAMILY Plant: herbs (annual or perennial), some shrubs, rarely vines or trees. Stem: Root: Often with tubers, rhizomes, stolons, or fleshy roots Leaves: mostly simple, some compound, alternate or opposite, rarely whorled. Flowers: flower head supported by an involucre (whorl of green bracts); each head composed of small flowers (composite) of flat ray-like (ligulate) flowers on the outside (ray flowers) and central tube-like flowers (disk flowers) – some species may have only one or the other. Calyx absent or modified into hairs, bristles, scales or a crown (pappus); 5 stamens (syngenesious -united by anthers); 5 united petals (sympetalous), receptacle may also have hairs or bristles. Both pappus and receptacle hairs/bristles may be used in ID. Fruit: achene (small, one-seeded, inferior ovule, 2 carpels, hard shell fruit) often with persisting crowned pappus which helps with seed dispersal. Other: Very large group, 1-2,000 genera, 20,000+ species. Dicotyledons Group WARNING – family descriptions are only a layman’s guide and should not be used as definitive ASTERACEAE – ASTER FAMILY Tall Blacktip Ragwort; Senecio atratus Greene Arrowleaf Ragwort; Senecio triangularis Hook. Common Groundsel [Old-Man-In-The-Spring]; Senecio vulgaris L. (Introduced) Starry Rosinweed; Silphium asteriscus L. [Wholeleaf] Rosinweed; Silphium integrifolium Michx. Compass Plant; Silphium laciniatum L. Cup Plant [Indian Cup]; Silphium perfoliatum L. Prairie-Dock [Prairie Rosenweed]; Silphium terebinthinaceum Jacq. var. terebinthinaceum Yellow-Flowered [Hairy; Large-Flowered] Leafcup; Smallanthus uvedalius (L.) Mack. ex Small Atlantic Goldenrod; Solidago arguta Aiton Blue-Stemmed [Wreath] Goldenrod; Solidago caesia L. Canadal [Tall] Goldenrod; Solidago canadensis L. and Solidago altissima L. -

Floristic Quality Assessment Report

FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT IN INDIANA: THE CONCEPT, USE, AND DEVELOPMENT OF COEFFICIENTS OF CONSERVATISM Tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) the State tree of Indiana June 2004 Final Report for ARN A305-4-53 EPA Wetland Program Development Grant CD975586-01 Prepared by: Paul E. Rothrock, Ph.D. Taylor University Upland, IN 46989-1001 Introduction Since the early nineteenth century the Indiana landscape has undergone a massive transformation (Jackson 1997). In the pre-settlement period, Indiana was an almost unbroken blanket of forests, prairies, and wetlands. Much of the land was cleared, plowed, or drained for lumber, the raising of crops, and a range of urban and industrial activities. Indiana’s native biota is now restricted to relatively small and often isolated tracts across the State. This fragmentation and reduction of the State’s biological diversity has challenged Hoosiers to look carefully at how to monitor further changes within our remnant natural communities and how to effectively conserve and even restore many of these valuable places within our State. To meet this monitoring, conservation, and restoration challenge, one needs to develop a variety of appropriate analytical tools. Ideally these techniques should be simple to learn and apply, give consistent results between different observers, and be repeatable. Floristic Assessment, which includes metrics such as the Floristic Quality Index (FQI) and Mean C values, has gained wide acceptance among environmental scientists and decision-makers, land stewards, and restoration ecologists in Indiana’s neighboring states and regions: Illinois (Taft et al. 1997), Michigan (Herman et al. 1996), Missouri (Ladd 1996), and Wisconsin (Bernthal 2003) as well as northern Ohio (Andreas 1993) and southern Ontario (Oldham et al. -

Plant Identification Presentation

Today’s Agenda ◦ History of Plant Taxonomy ◦ Plant Classification ◦ Scientific Names ◦ Leaf and Flower Characteristics ◦ Dichotomous Keys Plant Identification Heather Stoven What do you gain Looking at plants more closely from identifying plants? Why is it ◦ How do plants relate to each other? How are they important? grouped? • Common disease and insect problems • Cultural requirements • Plant habit • Propagation methods • Use for food and medicine Plant Classification Plant Classification Group each plant into a specific category Group each plant into a specific category Maple Spiraea Viburnum Crabapple Maple Spiraea Apple tree Ash Viburnum Crabapple Daylily Geranium Apple tree Ash Tomato Poinsettia Daylily Geranium TREES Oak Pepper Tomato Poinsettia Weeping willow Mint Oak Pepper Petunia Euonymus Weeping willow Mint Petunia Euonymus OS-Plant ID.ppt, page 1 Plant Classification Plant Classification Group each plant into a specific category Group each plant into a specific category Maple Spiraea Maple Spiraea Viburnum Crabapple Viburnum Crabapple Apple tree Ash Ornamental Apple tree Ash Edible Daylily Geranium Flowering Daylily Geranium Tomato Poinsettia Plants Tomato Poinsettia Crops Oak Pepper Oak Pepper Weeping willow Mint Weeping willow Mint Petunia Euonymus Petunia Euonymus Carolus Linnaeus Plant Taxonomy The Father of Taxonomy ◦ Identifying, classifying and assigning ◦ Swedish botanist scientific names to plants ◦ Developed binomial ◦ Historical botanists trace the start of nomenclature taxonomy to one of Aristotle’s students, Theophrastus (372-287 B.C.), but he didn’t ◦ Cataloged plants based on create a scientific system natural relationships—primarily flower structures (male and ◦ He relied on the common groupings of female sexual organs) folklore combined with growth: tree, shrub, undershrub or herb ◦ Published Species Naturae in ◦ Detected the process of germination and 1735 and Species Plantarum in realized the importance of climate and soil 1753 to plants ◦ Then, along came Linnaeus…. -

ABSTRACTS 117 Systematics Section, BSA / ASPT / IOPB

Systematics Section, BSA / ASPT / IOPB 466 HARDY, CHRISTOPHER R.1,2*, JERROLD I DAVIS1, breeding system. This effectively reproductively isolates the species. ROBERT B. FADEN3, AND DENNIS W. STEVENSON1,2 Previous studies have provided extensive genetic, phylogenetic and 1Bailey Hortorium, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853; 2New York natural selection data which allow for a rare opportunity to now Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY 10458; 3Dept. of Botany, National study and interpret ontogenetic changes as sources of evolutionary Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, novelties in floral form. Three populations of M. cardinalis and four DC 20560 populations of M. lewisii (representing both described races) were studied from initiation of floral apex to anthesis using SEM and light Phylogenetics of Cochliostema, Geogenanthus, and microscopy. Allometric analyses were conducted on data derived an undescribed genus (Commelinaceae) using from floral organs. Sympatric populations of the species from morphology and DNA sequence data from 26S, 5S- Yosemite National Park were compared. Calyces of M. lewisii initi- NTS, rbcL, and trnL-F loci ate later than those of M. cardinalis relative to the inner whorls, and sepals are taller and more acute. Relative times of initiation of phylogenetic study was conducted on a group of three small petals, sepals and pistil are similar in both species. Petal shapes dif- genera of neotropical Commelinaceae that exhibit a variety fer between species throughout development. Corolla aperture of unusual floral morphologies and habits. Morphological A shape becomes dorso-ventrally narrow during development of M. characters and DNA sequence data from plastid (rbcL, trnL-F) and lewisii, and laterally narrow in M.