Master Engelsk 2007 Morthaugen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

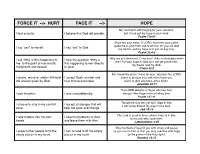

FORCE IT FACE IT HOPE Handout

FORCE IT --> HURT FACE IT --> HOPE My soul faints with longing for your salvation, ! I fear scarcity. I believe that God will provide. but I have put my hope in your word.! Psalm 119:81 Show me your ways, O LORD, teach me your paths; ! guide me in your truth and teach me, for you are God ! I say “yes” to myself. I say “yes” to God. my Savior, and my hope is in you all day long. ! Psalm 25:4-5 I ask “Why is this happening to I take the question “Why is Why are you downcast, O my soul? Why so disturbed within me? Put your hope in God, for I will yet praise him, ! me” to the point of narcissistic this happening to me” directly my Savior and my God.! martyrdom and despair. to God. Psalm 42:5 For I know the plans I have for you," declares the LORD, I ignore, mis-use, and/or withhold I accept God’s answer and "plans to prosper you and not to harm you, ! the answer given by God. trust Him to know best. plans to give you hope and a future.! Jeremiah 29:11 The LORD delights in those who fear him, ! I pick favorites. I love unconditionally. who put their hope in his unfailing love.! Psalm 147:11 Though he slay me, yet will I hope in him; ! I choose to stay in my comfort I accept challenges that will I will surely defend my ways to his face.! zone. help me grow and change. Job 13:15 The Lord is good to those whose hope is in him, ! I take matters into my own I take my problems to God to the one who seeks him; ! hands. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Living Clean the Journey Continues

Living Clean The Journey Continues Approval Draft for Decision @ WSC 2012 Living Clean Approval Draft Copyright © 2011 by Narcotics Anonymous World Services, Inc. All rights reserved World Service Office PO Box 9999 Van Nuys, CA 91409 T 1/818.773.9999 F 1/818.700.0700 www.na.org WSO Catalog Item No. 9146 Living Clean Approval Draft for Decision @ WSC 2012 Table of Contents Preface ......................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter One Living Clean .................................................................................................................. 9 NA offers us a path, a process, and a way of life. The work and rewards of recovery are never-ending. We continue to grow and learn no matter where we are on the journey, and more is revealed to us as we go forward. Finding the spark that makes our recovery an ongoing, rewarding, and exciting journey requires active change in our ideas and attitudes. For many of us, this is a shift from desperation to passion. Keys to Freedom ......................................................................................................................... 10 Growing Pains .............................................................................................................................. 12 A Vision of Hope ......................................................................................................................... 15 Desperation to Passion .............................................................................................................. -

United States District Court Central District Of

Case2:85-cv-04544-DMG-AGRDocument1161-1 Filed08/09/21 Page1 of 31 PageID #:44271 1 C ENTER FOR H UMANR IGHTS & C ONSTITUTIONALL AW 2 Carlos R. Holguín (90754) 256 South Occidental Boulevard 3 Los Angeles, CA 90057 4 Telephone: (213) 388-8693 Email: [email protected] 5 6 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 7 Additionalcounsellistedon followingpage 8 9 10 11 UNITEDSTATES DISTRICT COURT 12 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 13 WESTERN DIVISION 14 15 JENNY LISETTE FLORES, et al., No. CV 85-4544-DMG-AGRx 16 Plaintiffs, MEMORANDUM INSUPPORT OF 17 MOTION TO ENFORCE SETTLEMENT REEMERGENCY INTAKE SITES 18 v. Hearing: September 10, 2021 19 M ERRICK G ARLAND, Attorney General of the UnitedStates, et al., Time: 9:30 a.m. 20 Hon. Dolly M. Gee 21 Defendants. 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 1 Case2:85-cv-04544-DMG-AGRDocument1161-1 Filed08/09/21 Page2 of 31 PageID #:44272 1 NATIONALCENTER FOR YOUTHLAW 2 Leecia Welch (Cal. Bar No. 208741) Neha Desai (Cal. RLSA No. 803161) 3 Mishan Wroe (Cal. Bar No. 299296) 4 Melissa Adamson (Cal. Bar No. 319201) Diane de Gramont (Cal. Bar No. 324360) 5 1212 Broadway,Suite 600 Oakland, CA 94612 6 Telephone: (510) 835-8098 Email: [email protected] 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 2 MTE RE EMERGENCY INTAKE SITES CV 85-4544-DMG-AGRX Case2:85-cv-04544-DMG-AGRDocument1161-1 Filed08/09/21 Page3 of 31 PageID #:44273 1 TABLEOF CONTENTS 2 3 4 I. -

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

y f !, 2.(T I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings MAYA ANGELOU Level 6 Retold by Jacqueline Kehl Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 Growing Up Black 1 Chapter 2 The Store 2 Chapter 3 Life in Stamps 9 Chapter 4 M omma 13 Chapter 5 A New Family 19 Chapter 6 Mr. Freeman 27 Chapter 7 Return to Stamps 38 Chapter 8 Two Women 40 Chapter 9 Friends 49 Chapter 10 Graduation 58 Chapter 11 California 63 Chapter 12 Education 71 Chapter 13 A Vacation 75 Chapter 14 San Francisco 87 Chapter 15 Maturity 93 Activities 100 / Introduction In Stamps, the segregation was so complete that most Black children didn’t really; absolutely know what whites looked like. We knew only that they were different, to be feared, and in that fear was included the hostility of the powerless against the powerful, the poor against the rich, the worker against the employer; and the poorly dressed against the well dressed. This is Stamps, a small town in Arkansas, in the United States, in the 1930s. The population is almost evenly divided between black and white and totally divided by where and how they live. As Maya Angelou says, there is very little contact between the two races. Their houses are in different parts of town and they go to different schools, colleges, stores, and places of entertainment. When they travel, they sit in separate parts of buses and trains. After the American Civil War (1861—65), slavery was ended in the defeated Southern states, and many changes were made by the national government to give black people more rights. -

The Buffered Slayer: a Search for Meaning in a Secular Age

Willinger 1 The Buffered Slayer: A Search for Meaning in a Secular Age A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English By Kari Willinger 1 May 2018 Willinger 2 Liberty University College of Arts and Sciences Master of Arts in English Student Name: Kari Willinger ______________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Marybeth Baggett, Thesis Chair Date ______________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Stephen Bell, First Reader Date ______________________________________________________________________________ Mr. Alexander Grant, Second Reader Date Willinger 3 Acknowledgments I would like to express my very deep appreciation to: Dr. Baggett, for the encouragement to think outside of the box and patience through the many drafts and revisions; Dr. Bell and Mr. Grant, for providing insightful feedback and direction; My family for prayer and embracing my crazy; My roommates for the endless hours of Buffy marathons; My friends for the continued love and emotional and moral support. You have all challenged and encouraged me through the process of writing this thesis, and I am incredibly grateful to each and every one of you. Willinger 4 Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………5 Chapter One - The Stakes of Morality: Buffy as Moral Authority …...………….……........15 Chapter Two - Losing Faith: The Buffered Self as Fragmented Identity ……...…..……….29 Chapter Three - The Soulful Undead: Spike’s Dissatisfied Fulfillment ….……….....……..42 Chapter Four - Which Will: A Longing for Enchantment ...…………………………...........56 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………71 Works Cited …………………………………………………………………………….….……77 Willinger 5 Introduction “I knew that everyone I cared about was all right. I knew it. Time ... didn’t mean anything... nothing had form ... but I was still me, you know? And I was warm .. -

Badlands, Blank Space, Border Vacuums, Brown Fields, Conceptual Nevada, Dead Zones …

10 ISSN: 1755-068 www.field-journal.org vol.1 (1) …badlands, blank space, border vacuums, brown fields, conceptual Nevada, Dead Zones … 1 The term I have used to describe these …badlands, blank space, border vacuums, brown fields, spaces, which is reflected in all the conceptual Nevada, Dead Zones1, derelict areas,ellipsis other terms mentioned above, is ‘dead zone’. The term was taken directly spaces, empty places, free space liminal spaces, from the jargon of urban planners, and from a particular case of such space in ,nameless spaces, No Man’s Lands, polite spaces, , post Tel Aviv (cf. Gil Doron,‘Dead Zones, architectural zones, spaces of indeterminacy, spaces of Outdoor Rooms and the Possibility of Transgressive Urban Space’ in K. Franck uncertainty, smooth spaces, Tabula Rasa, Temporary and Q. Stevens (eds.), Loose Space: Autonomous Zones, terrain vague, urban deserts, Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life (New York: Routledge, 2006). The vacant lands, voids, white areas, Wasteland... SLOAPs term should be read in two ways: one with inverted commas, indicating my Gil M. Doron argument that an area or space cannot be dead or a void, tabula rasa etc. The second reading collapses the term in on itself – while the planners see a dead zone, I argue that it is not the area which If the model is to take every variety of form, then the matter in which the is dead but it is the zone, or zoning, and the assumption that whatever exists model is fashioned will not be duly prepared, unless it is formless, and (even death) in this supposedly delimited free from the impress of any of these shapes which it is hereafter to receive area always transcends the assumed from without.2 boundaries and can be found elsewhere. -

The Empty House by Richard J. Hand the ESTATE

79 This piece has an accompanying audio file. ANNOUNCER: The Empty House by Richard J. Hand THE ESTATE AGENT IS IN THE LOFT OF AN EMPTY HOUSE. THERE IS BIRDSONG AND TRAFFIC IN BACKGROUND ESTATE AGENT: I’ve been an estate agent for twenty-five years. Sold all kinds of houses. And other properties. Hidden gems and no hopers – I’ve got them on, then swiftly off, the books. I know the language you see, it’s all in the language. I can call a complete dump an opportunity and a punter will buy it – literally. I’ve helped vendors make a mint like that. At the same time, despite my best efforts I’ve seen others let emotion get the better of them and let a place go for a snip. In my experience, empty houses have a sadness to them – a melancholia. Others can brim full of sweet memories. Some almost bleed with lost opportunities or unfounded dreams. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve taken a key and opened the door to an empty house. Stepping over the threshold. An empty house is always lifeless. Didn’t someone once talk of the breathlessness of empty houses? It’s true. Until I went to one particular house. This house. The house I am in now. I’d just gone to measure up. Done it a thousand times. And I always like to talk my way through it. Dictaphone in one hand, tape measure in the other. Type it up later. Used to have cute little cassette tapes. -

Englishness in Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Pateman, Matthew. « “You Say Tomato” Englishness in Buffy the Vampire Slayer », Cercles 8 (2003) : 103-113 <www.cercles.com>. ©Cercles 2003. Toute reproduction, même partielle, par quelque procédé que ce soit, est in- terdite sans autorisation préalable (loi du 11 mars 1957, al. 1 de l’art. 40). ISSN : 1292-8968. Matthew Pateman The University of Hull “YOU SAY TOMATO” Englishness in Buffy the Vampire Slayer After finally managing to have Lolita published, Vladimir Nabokov had to confront the various criticisms and concerns regarding his novel. Apart from the obvious attacks against its supposed immorality, Nabokov also had to contend with a range of interpretations that, for the great exponent of subtlety and care, seemed to be reductive and simplifying in the extreme. Among these was included a reading that tended to see the figure of Humbert as represen- tative of Old Europe and which read Lolita herself as synecdochic of America. Thus the novel becomes a tale of brash, crude, young America being debau- ched by the sophisticated but depraved and perverse Europe (Nabokov, “On a book entitled Lolita” 314). While there may be some critical interest in this reading, on its own it inevitably serves to reduce this colossally self-conscious, allusive, intelligent and moving work to the level of a rather blunt allegory. By only allowing the characters to act in one fashion, here as the ciphers of an al- legorical puzzle, the text loses much of its multiplicity and also the thematic, sympathetic and inter-personal resonances it should be allowed. Buffy the Vampire Slayer is not, of course, Lolita. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

2009 Annual Report

2009 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs PALEYDOCEVENTS ..................................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST .......................................................................................................................................19 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ..........................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ..........................................................................................21 Robert M. -

The Green Caldron Includes Miss Constance Nicholas and Messrs

LI E) R,AR.Y OF THE UN IVLR.SITY or ILLI-NOIS 8l0o5 GR . Vo 17-18 COPeS hME Green Galdron QQT2 3 1947 A Magazine of Freshman Writing UIIUasiTl 0^ ILLIKOIS Charles N. Watkins: Tex 1 John F.May : Fat, Dumb, and Happy 3 Jim Koeller: So Help Me, God 5 John W. Kuntz: Fascism 6 Robert M. Albert: Catalyst Cataclysmic — Sarajevo 1914 ... 8 William H. Hitt: A Farewell to Arms hy KmcstHeraingwsiy . 11 Robin Good: First Flight 12 Dorothy Sherrard: Beyond the Blue Horizon 15 Nevzat Gomec: The American Picture of Turkey 21 D. Erickson: What It Means to Sec 21 Peter Fleischmann: Opening Night 22 Sigrid Iben: A Night in Kam's 23 Leroy F. Mumford: Poi 24 Charles N. Watkins: One More Load 26 Gerald O'Mara: Interpreting the Public Opinion Polls .... 29 Haluk Akol: Your Mood and Ours 33 Gene Reiley: One of a Kind 34 Ralph Brown: Rain 35 Lawrence Zuckerman: Keep That Last Team! 36 William H. Kellogg: Farmers 37 John Weiter: Thanks! 38 Rhet as Writ 40 VOL. 17, NO. 1 NOVEMBER, 1947 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS T,HE Green Caldron is published four times a year by the Rhetoric Staff at the University of Illinois. Material is chosen from themes and examinations written by freshmen in the Uni- versity including the Navy Pier and Galesburg divisions, and the high school branches. Permission to publish is obtained for all full themes, including those published anonymousl)'. Parts of themes, however, are published at the discretion of the committee in charge. The committee in charge of this issue of The Green Caldron includes Miss Constance Nicholas and Messrs.