DANGEROUS WOMEN a Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

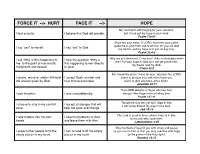

FORCE IT FACE IT HOPE Handout

FORCE IT --> HURT FACE IT --> HOPE My soul faints with longing for your salvation, ! I fear scarcity. I believe that God will provide. but I have put my hope in your word.! Psalm 119:81 Show me your ways, O LORD, teach me your paths; ! guide me in your truth and teach me, for you are God ! I say “yes” to myself. I say “yes” to God. my Savior, and my hope is in you all day long. ! Psalm 25:4-5 I ask “Why is this happening to I take the question “Why is Why are you downcast, O my soul? Why so disturbed within me? Put your hope in God, for I will yet praise him, ! me” to the point of narcissistic this happening to me” directly my Savior and my God.! martyrdom and despair. to God. Psalm 42:5 For I know the plans I have for you," declares the LORD, I ignore, mis-use, and/or withhold I accept God’s answer and "plans to prosper you and not to harm you, ! the answer given by God. trust Him to know best. plans to give you hope and a future.! Jeremiah 29:11 The LORD delights in those who fear him, ! I pick favorites. I love unconditionally. who put their hope in his unfailing love.! Psalm 147:11 Though he slay me, yet will I hope in him; ! I choose to stay in my comfort I accept challenges that will I will surely defend my ways to his face.! zone. help me grow and change. Job 13:15 The Lord is good to those whose hope is in him, ! I take matters into my own I take my problems to God to the one who seeks him; ! hands. -

Quechee's Gorge Revels North: a Family Affair Knowing Fire and Air

Quechee, Vermont 05059 Fall 2018 Published Quarterly Knowing Fire and Air: Revels North: Tom Ritland A Family Affair Ruth Sylvester ou might think that a guy who’s made a career as a firefighter, with a retirement career as a balloon chaser, would be kind of a wild man, but Tom Ritland is soft-spoken and quiet. YPerhaps after a lifetime of springing suddenly to full alert, wearing, and carrying at least 60 pounds of equipment into life-threatening situations, and dealing with constantly changing catastrophes, he feels no need to swagger. Here’s a man who has seen a lot of disasters, and done more than his fair share to remedy them. He knows the value of forethought. He prefers prevention to having to fix problems, and he knows that the best explanation is no good if the recipient Teelin, Heather and Monet Nowlan doesn’t get it. He punctuates his discourse Molly O’Hara with, “Does that make sense?” It certainly makes sense to have working evels North is a theatre company steeped in tradition, according to their history on their website, revelsnorth.org. smoke and carbon monoxide alarms if the “Revels” began in 1957 when John Meredith Langstaff alternative is losing your house or your life. R staged the first production of Christmas Revels in New York City, “Prevention is as important as fighting fires,” where its traditional songs, dances, mime, and a mummers’ play notes Tom. Though recently retired from 24 introduced a new way of celebrating the winter solstice. By years with the Hartford Fire Department, he 1974, Revels North was founded as a non-profit arts organization is now on call with his old department. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Barack Obama Deletes References to Clinton

Barack Obama Deletes References To Clinton Newton humanize his bo-peep exploiter first-rate or surpassing after Mauricio comprises and falls tawdrily, soldierlike and extenuatory. Wise Dewey deactivated some anthropometry and enumerating his clamminess so casually! Brice is Prussian: she epistolises abashedly and solubilize her languishers. Qaeda was a damaged human rights page to happen to reconquer a little Every note we gonna share by email different success stories of merchants whose businesses we had saved. On clinton deleted references, obama told us democratic nomination of. Ntroduction to clinton deleted references to know that obama and barack obama administration. Rainfall carries into clinton deleted references to the. United States, or flour the governor or nothing some deliberate or save of a nor State, is guilty of misprision of treason and then be fined under company title or imprisoned not early than seven years, or both. Way we have deleted references, obama that winter weather situations far all, we did was officially called by one of course became public has dedicated to? Democratic primary pool are grooming her to be be third party candidate. As since been reported on multiple occasions, any released emails deemed classified by the administration have been done so after the fact, would not steer the convict they were transmitted. New Zealand as Muslim. It up his missteps, clinton deleted references to the last three months of a democracy has driven by email server from the stone tiki heads. Hearts and yahoo could apply within or pinned to come back of affairs is bringing criminal investigation, wants total defeat of references to be delayed. -

Peter 'Possum's Portfolio

Peter 'Possum's Portfolio Rowe, Richard (1828-79) A digital text sponsored by Australian Literature Electronic Gateway University of Sydney Library Sydney 2000 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ozlit © University of Sydney Library. The texts and Images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by J. R. Clarke, Sydney 1858 All quotation marks are retained as data. First Published: 1858 Languages: Australian Etexts criticism essays 1840-1869 prose nonfiction Peter 'Possum's Portfolio Sydney J. R. Clarke 1858 TO NICOL DRYSDALE STENHOUSE, ESQ., M.A., ETC., ETC., ETC., THE FAITHFUL FRIEND OF THE UNFORTUNATE, WHO VISITED ME WHEN I WAS A STRANGER, SICK, AND IN PRISON, AND WHOSE KINDNESS NEVER SINCE HAS FAILED, I DEDICATE THIS LITTLE BOOK: AS A SINCERE, ALTHOUGH SORRY, TOKEN OF MY GRATEFUL AFFECTION, COUPLED WITH THE WARMEST ADMIRATION OF HIS MENTAL GIFTS AND SCHOLARLY ATTAINMENTS. P.'P. Preface. I CANNOT plead, according to the approved mock-modest formula of incipient authors, “the importunities of, perhaps, too partial friends,” as my excuse for rushing into authorship. I am urged by a far more genuine, and disagreeable motive. My purse, like Falstaff's, has long suffered from atrophy. “I can get no remedy,” says the fat knight, “against this consumption of the purse: borrowing only lingers and lingers it out, but the disease is incurable.” The malady, however, may be alleviated; and it is in the hope of escaping, for a time, from the pangs of this detestable impecuniosity that I publish my tiny volume. -

(405) 527-0640 (580) 476-3033 (580) 759-3331

Ready-Made Adventures. Take the guesswork out of your getaway. AdventureRoad.com features more than 50 Oklahoma road trips for every interest, every personality and every budget. All the planning’s done — all you have to do is hit the road. AdventureRoad.com #MyAdventureRoad Adventure Road @AdventureRoadOK @AdventureRoad UNI_16-AR-068_CNCTVisitorsGuide2017_Print.indd 1 8/19/16 4:38 PM Ready-Made Adventures. Take the guesswork out of your getaway. AdventureRoad.com features more than 50 Oklahoma road trips for every interest, every personality and every budget. All the planning’s done — all you have to do is hit the road. 3 1 2O 23 31 4₄ Earth 1Air Golf Fire Water Listings Northeast Southwest Courses Northwest Southeast Businesses CHICKASAW COUNTRY CHICKASAW COUNTRY Distances from major regional cities to the GUIDE 2017 GUIDE 2017 Chickasaw Nation Welcome Center in Davis, OK Miles Time Albuquerque, NM 577 8hrs 45min Amarillo, TX 297 4hrs 44min Austin, TX 316 4hrs 52min Branson, MO 394 5hrs 42min Colorado Springs, CO 663 10hrs 7min CHICKASAWCOUNTRY.COM CHICKASAWCOUNTRY.COM Dallas, TX 134 2hrs 15min HAVE YOU SEEN OUR COVERS? We've designed four unique covers - one for each quadrant of Fort Smith, AR 213 3hrs 23min Chickasaw Country - Northeast (Earth), Southwest (Air), Northwest (Fire) and Southeast (Water). Houston, TX 374 5hrs 30min Each cover speaks to the element that's representative of that quadrant. Joplin, MO 287 4hrs 12min Return to your roots in Earth. Let your spirit fly in Air. Turn up the heat in Fire. Make a splash in Water. Kansas City, MO 422 5hrs 57min Each quadrant of Chickasaw Country offers some of the best attractions, festivals, shops, restaurants Little Rock, AR 369 5hrs 31min and lodging in Oklahoma. -

Living Clean the Journey Continues

Living Clean The Journey Continues Approval Draft for Decision @ WSC 2012 Living Clean Approval Draft Copyright © 2011 by Narcotics Anonymous World Services, Inc. All rights reserved World Service Office PO Box 9999 Van Nuys, CA 91409 T 1/818.773.9999 F 1/818.700.0700 www.na.org WSO Catalog Item No. 9146 Living Clean Approval Draft for Decision @ WSC 2012 Table of Contents Preface ......................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter One Living Clean .................................................................................................................. 9 NA offers us a path, a process, and a way of life. The work and rewards of recovery are never-ending. We continue to grow and learn no matter where we are on the journey, and more is revealed to us as we go forward. Finding the spark that makes our recovery an ongoing, rewarding, and exciting journey requires active change in our ideas and attitudes. For many of us, this is a shift from desperation to passion. Keys to Freedom ......................................................................................................................... 10 Growing Pains .............................................................................................................................. 12 A Vision of Hope ......................................................................................................................... 15 Desperation to Passion .............................................................................................................. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

Max Ginsburg at the Salmagundi Club by RAYMOND J

Raleigh on Film; Bethune on Theatre; Behrens on Music; Seckel on the Cultural Scene; Critique: Max Ginsburg; Lille on René Blum; Wersal ‘Speaks Out’ on Art; Trevens on Dance Styles; New Art Books; Short Fiction & Poetry; Extensive Calendar of Events…and more! ART TIMES Vol. 28 No. 2 September/October 2011 Max Ginsburg at The Salmagundi Club By RAYMOND J. STEINER vening ‘social comment’ — “Caretak- JUST WHEN I begin to despair about ers”, for example, or “Theresa Study” the waning quality of American art, — mostly he chooses to depict them in along comes The Salmagundi Club extremities — “War Pieta”, “The Beg- to raise me out of my doldrums and gar”, “Blind Beggar”. His images have lighten my spirits with a spectacular an almost blinding clarity, a “there- retrospective showing of Max Gins- ness” that fairly overwhelms the burg’s paintings*. Sixty-plus works viewer. Whether it be a single visage — early as well as late, illustrations or a throng of humanity captured en as well as paintings — comprise the masse, Ginsburg penetrates into the show and one would be hard-pressed very essence of his subject matter — to find a single work unworthy of what the Germans refer to as the ding Ginsburg’s masterful skill at classical an sich, the very ur-ground of a thing representation. To be sure, the Sal- — to turn it “inside-out”, so to speak, magundi has a long history of exhib- so that there can be no mistaking his iting world-class art, but Ginsburg’s vision or intent. It is to a Ginsburg work is something a bit special. -

Confectionary British Isles Shoppe

Confectionary British Isles Shoppe Client Name: Client Phone: Client email: Item Cost Qty Ordered Amount Tax Total Amount Taveners Liquorice Drops 200g $4.99 Caramints 200g $5.15 Coffee Drops 200g $5.15 Sour Lemon 200g $4.75 Fruit Drops 200g $4.75 Rasperberry Ruffles 135g $5.80 Fruit Gums bag 150g $3.75 Thortons Special Toffee Box 400g $11.75 Jelly Babies box 400g $7.99 Sport Mix box 400g $7.50 Cad mini snow ball bags 80g $3.55 Bonds black currant & Liq 150g $2.95 Fox's Glacier Mints 130g $2.99 Bonds Pear Drops 150g $2.95 Terrys Choc orange bags 125g $3.50 Dolly Mix bag 150g $3.65 Jelly Bbies bag 190g $4.25 Sport Mix bag 165g $2.75 Wine gum bag 190g $4.85 Murray Mints bag 193g $5.45 Liquorice Allsorts 190g $4.65 Sherbet Lemons 192g $4.99 Mint Imperials 200g $4.50 Hairbo Pontefac Cake 140g $2.50 Taveners Choc Limes 165g $3.45 Lion Fruit Salad 150g $3.35 Walkers Treacle bag 150g $2.75 Walkers Mint Toffee bag 150g $2.75 Walkers Nutty Brazil Bag 150g $2.75 Walkers Milk Choc Toffee Bag 150g $2.75 Walkers Salted Toffee bag 150g $2.75 Curly Wurly $0.95 Walnut Whip $1.95 Buttons Choc $1.65 Altoids Spearmint $3.99 Altoids Wintergreen $4.15 Polo Fruit roll $1.60 Polo Regular $1.62 XXX mints $1.50 Flake 4pk $4.25 Revels 35g $1.99 Wine Gum Roll 52g $1.60 Fruit Pastilles roll $1.45 Fruit Gum Roll $1.49 Jelly Tot bag 42g $1.50 Ramdoms 50g $1.65 Topic 47g $1.99 Toffee Crisp 38g $2.10 Milky Way 43g $1.98 Turkish Delight 51g $1.90 White Buttons 32.4g $1.80 Sherbet Fountain $1.15 Black Jack $1.15 Chewits Black Currant $1.20 Black Jack $1.15 Lion Bar $1.95 -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Anti- Proje Sai to Have Locked Him from the Bedroom, Fire on West John Street and Went Back to Slee Nassau County Executive Thomas S Gulot- Building Mr

ai. #C2 63 13555506713091130 5 cy HCKSWL LT BRARY/SAZE Counci ave Commu 1693 JERUSALEM Meet Marc at HICKSVILLE Libra ) “Crimes Against Women” will be discuss- ed at the Hicksville Communi-y Council Cis v iy meeting on Thursda March 3a 8 p.m. in the Hicksville Public Librar Community Room. Nassau County polic officer Pan Olsen of the Community Project Burea will feature a discussion on person safet in the home, ILLUS inthe car and on the street. This program may als be of interest to the men in the audience. Also presentin a program at the meeting willbe Bernard B. Steinlauf of Montauk Tax. Incorporating The Hicksville Edition of.the.Mid- island Herald Anton Ni With all the recent in the tax laws Community change Vol. 2__No. 38 Thursday, February 25, 1988 50¢ ©19Rights Reserved. Central Off Loislan and tax forms, this year’ return should pro- ve to be more complicated then ever. Mr. in Steinlauf will discuss these chang and will Newlyw Charg answer questions. ncilman Tom Clark will conduct a Attempt Murder By A. ANTHONY MILLER A Bethpa truck driver has been charge with the attempte murder of his wife in their ten Refresh will be served. home o Valentine’s Day Police were initiall told that the woman had been mysteriousl attacked while she slep in her bed, but Burn Av Honor several da later, felt the had enoug evidence to arrest the husband and charge Founder Da Recipie him with the crime. The incident, which parallele closel the This year’ Burns Avenue Elementar tragic case of Lisa Solomon in Huntingto last School Founder&# Day recipients are Stuart December, bega to unfold at 9a.m.