The Buffered Slayer: a Search for Meaning in a Secular Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UA 12 Steps 04072020

UA QUESTIONS Read step one out of the AA 12 and 12 then answer the questions. 1. What symptoms of underearning have you experienced or are you currently experiencing? (Hint: look at the symptoms list) 2. How have you tried to control or overcome underearning on your own efforts? 3. In what ways has your under earning defeated you...what did you do in response to this feeling of defeat? (Hint: Quit jobs, use credit cards, fight with co-workers) 4. How is underearning making your life unmanageable (Having no money, job or clients, debting, eviction) 5. How have you tried to make under earning work? (Hint: working 3 jobs, working overtime, cheating on the job) 6. What do you consider to be an underearning job or client? 7. How did you react to other people's prosperity around you and why? (Hint: Undercut them, criticize them, gossip about them, conspire against them, etc) 8. In what instances have you had a bad attitude about being an employee or a subordinate? How did you express this bad attitude? 9. In what instances have you slacked off on the job, disappointing supervisors, co-workers, family members or spouses? 10. How have you tried to top or outshine your co-workers in order to get a raise or promotion as a solution to your under earning? 11. In what instances did you manipulate others to do your work for you because you felt the work was beneath you. Read step two out of the AA 12 and 12 then answer the questions. -

Adolescents, Virtual War, and the Government-Gaming Nexus

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Why We Still Fight: Adolescents, Virtual War, and the Government Gaming Nexus Margot A. Susca Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION WHY WE STILL FIGHT: ADOLESCENTS, VIRTUAL WAR, AND THE GOVERNMENT- GAMING NEXUS By MARGOT A. SUSCA A dissertation submitted to the School of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Margot A. Susca defended this dissertation on February 29, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jennifer M. Proffitt Professor Directing Dissertation Ronald L. Mullis University Representative Stephen D. McDowell Committee Member Arthur A. Raney Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my mother iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Jennifer M. Proffitt, Ph.D., for her unending support, encouragement, and guidance throughout this process. I thank her for the endless hours of revision and counsel and for having chocolate in her office, where I spent more time than I would like to admit looking for words of inspiration and motivation. I also would like to thank my committee members, Stephen McDowell, Ph.D., Arthur Raney, Ph.D., and Ronald Mullis, Ph.D., who all offered valuable feedback and reassurance during these last two years. -

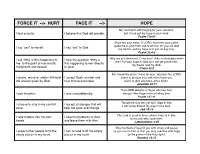

FORCE IT FACE IT HOPE Handout

FORCE IT --> HURT FACE IT --> HOPE My soul faints with longing for your salvation, ! I fear scarcity. I believe that God will provide. but I have put my hope in your word.! Psalm 119:81 Show me your ways, O LORD, teach me your paths; ! guide me in your truth and teach me, for you are God ! I say “yes” to myself. I say “yes” to God. my Savior, and my hope is in you all day long. ! Psalm 25:4-5 I ask “Why is this happening to I take the question “Why is Why are you downcast, O my soul? Why so disturbed within me? Put your hope in God, for I will yet praise him, ! me” to the point of narcissistic this happening to me” directly my Savior and my God.! martyrdom and despair. to God. Psalm 42:5 For I know the plans I have for you," declares the LORD, I ignore, mis-use, and/or withhold I accept God’s answer and "plans to prosper you and not to harm you, ! the answer given by God. trust Him to know best. plans to give you hope and a future.! Jeremiah 29:11 The LORD delights in those who fear him, ! I pick favorites. I love unconditionally. who put their hope in his unfailing love.! Psalm 147:11 Though he slay me, yet will I hope in him; ! I choose to stay in my comfort I accept challenges that will I will surely defend my ways to his face.! zone. help me grow and change. Job 13:15 The Lord is good to those whose hope is in him, ! I take matters into my own I take my problems to God to the one who seeks him; ! hands. -

Satan's Sibling - Poems

Poetry Series Satan's Sibling - poems - Publication Date: 2008 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Satan's Sibling(15/03/1990) I am a poetry enthusiast with a variety of poetry styles. Some are love poems, some are hate poems. But I guess that love and hate are the basis of life, Aren't they? (My motto for life is 'There is no God, he is a figment of our imagination. There is no Karma, we punish ourselves. No destiny, we choose our own path. No freedom. We are bound by our own laws. For now.) www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 1 Million Years Bc (Lyrics) They're calling me, the creatures of the nigh, Beautiful music, Animal instincts survived, the serpent tongue, so ancient before the dawn of time, Spread throughout the ages, On the blood of mankind. I've seen it all. From grace man falls, Babylon, curse of all creation, Winged serpent of the pit, Monstrosity. Ten thousand centuries ago, Cast down from heaven, To pillage below, The serpents eye, Still watching for it's easy prey, Feed upon the hopeless, the weak and afraid. I've seen it all. From grace men fall, Babylon, curse of all creation. Winged serpent of the pit, Monstrosity. 1 million yeasr bc x3 Satan's Sibling www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 2 8 Line Poem (Lyrics) The tactful cactus by your window Surveys the prairie of your room The mobile spins to its collision Clara puts her head between her paws They've opened shops down West side Will all the cacti find a home But the key to the city Is in the sun that pins the branches to the sky Satan's Sibling www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 3 A Desirable Complication I sit here in anguish, Silently suffering. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Living Clean the Journey Continues

Living Clean The Journey Continues Approval Draft for Decision @ WSC 2012 Living Clean Approval Draft Copyright © 2011 by Narcotics Anonymous World Services, Inc. All rights reserved World Service Office PO Box 9999 Van Nuys, CA 91409 T 1/818.773.9999 F 1/818.700.0700 www.na.org WSO Catalog Item No. 9146 Living Clean Approval Draft for Decision @ WSC 2012 Table of Contents Preface ......................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter One Living Clean .................................................................................................................. 9 NA offers us a path, a process, and a way of life. The work and rewards of recovery are never-ending. We continue to grow and learn no matter where we are on the journey, and more is revealed to us as we go forward. Finding the spark that makes our recovery an ongoing, rewarding, and exciting journey requires active change in our ideas and attitudes. For many of us, this is a shift from desperation to passion. Keys to Freedom ......................................................................................................................... 10 Growing Pains .............................................................................................................................. 12 A Vision of Hope ......................................................................................................................... 15 Desperation to Passion .............................................................................................................. -

United States District Court Central District Of

Case2:85-cv-04544-DMG-AGRDocument1161-1 Filed08/09/21 Page1 of 31 PageID #:44271 1 C ENTER FOR H UMANR IGHTS & C ONSTITUTIONALL AW 2 Carlos R. Holguín (90754) 256 South Occidental Boulevard 3 Los Angeles, CA 90057 4 Telephone: (213) 388-8693 Email: [email protected] 5 6 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 7 Additionalcounsellistedon followingpage 8 9 10 11 UNITEDSTATES DISTRICT COURT 12 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 13 WESTERN DIVISION 14 15 JENNY LISETTE FLORES, et al., No. CV 85-4544-DMG-AGRx 16 Plaintiffs, MEMORANDUM INSUPPORT OF 17 MOTION TO ENFORCE SETTLEMENT REEMERGENCY INTAKE SITES 18 v. Hearing: September 10, 2021 19 M ERRICK G ARLAND, Attorney General of the UnitedStates, et al., Time: 9:30 a.m. 20 Hon. Dolly M. Gee 21 Defendants. 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 1 Case2:85-cv-04544-DMG-AGRDocument1161-1 Filed08/09/21 Page2 of 31 PageID #:44272 1 NATIONALCENTER FOR YOUTHLAW 2 Leecia Welch (Cal. Bar No. 208741) Neha Desai (Cal. RLSA No. 803161) 3 Mishan Wroe (Cal. Bar No. 299296) 4 Melissa Adamson (Cal. Bar No. 319201) Diane de Gramont (Cal. Bar No. 324360) 5 1212 Broadway,Suite 600 Oakland, CA 94612 6 Telephone: (510) 835-8098 Email: [email protected] 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 2 MTE RE EMERGENCY INTAKE SITES CV 85-4544-DMG-AGRX Case2:85-cv-04544-DMG-AGRDocument1161-1 Filed08/09/21 Page3 of 31 PageID #:44273 1 TABLEOF CONTENTS 2 3 4 I. -

Young Writers Workshop History from Home

Young Writers Workshop History from Home June 15 – 19, 2020 Table of Contents Introduction by Stephanie Hemphill 2 Brynn Almond 3 Dameon Borders 7 Dashiell Coyier 13 Ellis Coyier 16 Mila Grothus 20 Hollin Hansen 23 Keelin Hansen 28 Margo Keller 32 Wesley McDowell 38 Bryn Mineck 42 Anika Shetye 47 Yatharth Sirohi 50 Keaton Steger 54 Sydney Thompson 58 Zoe Zhang 60 Each student’s object of inspiration precedes their historical fiction story. An introduction for each object is provided by the student. 1 There’s a common adage that “a picture is worth a thousand words,” and this year the young authors proved the theory true as they were tasked with writing about an historical photograph in a thousand words or less. We all have taken photographs which we could easily relay the story behind—the who, what, where, when and why of what’s happening in the picture. But in order to create a story around a photograph of a subject or person from a time period far removed from your own requires examination followed by research. You have to know how to read the photograph, how to employ visual literacy, and then dig into research to learn about what you observe. The young writers then created a fictional story by imagining life outside and beyond that singular historical moment captured on film. Their pictures inspired a thousand words. In previous years the Young Writer’s Workshop has been held at the museum where we have access to the museum vault, exhibits, additional museum staff, and the museum’s research library. -

170404 Whos in Charge Here

Who’s in Charge Here? April 4, 2017 Ajaan Suwat often talked about Ajaan Mun’s favorite themes for a Dhamma talk. One was the customs of the noble ones and the other was practicing the Dhamma in accordance with the Dhamma. The customs of the noble ones are customs that go against the customs of practicall! every nation on earth" because the! put the training of the mind first. The! put the Dhamma first. $t’s for this reason that the customs of the noble ones are closel! connected to the principle of practicing the Dhamma in accordance with the Dhamma, because that’s one of the two meanings of practicing the Dhamma in accordance with the Dhamma: $nstead of trying to change the Dhamma to fit !ou" !ou try to change !ourself to fit the Dhamma. The other meaning, as it’s defined in the &anon, is practicing for the sake of dispassion. This" too, goes against every custom" every culture in the world" all of which are aimed at passion. There’s the stor! in the &anon where some monks are going to a foreign country. After paying their respects to the Buddha, the! go to sa! goodb!e to Sariputta. And he asks them" ()hen someone in that countr! asks !ou" *)hat does !our teacher teach+’ what are !ou going to tell them+, And the monks sa!" ()e’d like to hear what !ou’d say., So Sariputta says that his first answer would be that his teacher teaches dispassion. Then he goes on to say intelligent people then ask" (Dispassion for what?, Most people in the world nowadays" however, wouldn’t even bother to ask. -

Serial Number ______

RIGID OWNERS MANUAL RIGID OWNERS MANUAL SERIAL NUMBER ______________________ OM_FOLDING_0907RevB I WARNING - READ THIS MANUAL DO NOT OPERATE THIS WHEELCHAIR WITHOUT FIRST READING AND UNDERSTANDING THIS OWNERS MANUAL. IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO UNDERSTAND THE WARNINGS, CAUTIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS, CONTACT YOUR TiLITE DEALER OR TiLITE CUSTOMER SUPPORT AT (800) 545-2266 BEFORE ATTEMPTING TO USE THIS WHEELCHAIR. IF YOU IGNORE THIS WARNING, YOU MAY FALL, TIP OVER OR LOSE CONTROL OF THE WHEELCHAIR AND SERIOUSLY INJURE YOURSELF OR OTHERS OR DAMAGE THE WHEELCHAIR. I WARNING - WHEELCHAIR SELECTION TILITE MANUFACTURES A WIDE VARIETY OF WHEELCHAIRS TO MEET THE VARIED NEEDS OF WHEELCHAIR USERS. HOWEVER, TILITE IS NOT YOUR HEALTH CARE ADVISOR, AND WE KNOW NOTHING ABOUT YOUR INDIVIDUAL CONDITION OR NEEDS. THEREFORE, THE FINAL SELECTION OF THE PARTICULAR MODEL, AND HOW IT IS ADJUSTED, AND THE TYPE OF OPTIONS AND ACCESSORIES NECESSARY REST SOLELY WITH YOU, THE WHEELCHAIR USER, AND THE HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONAL THAT IS ADVISING YOU. CHOOSING THE BEST CHAIR AND SETUP FOR YOUR SAFETY DEPENDS ON SUCH THINGS AS: 1. YOUR DISABILITY, STRENGTH, BALANCE AND COORDINATION; 2. THE TYPES OF HAZARDS YOU MUST OVERCOME IN DAILY USE (WHERE YOU LIVE AND WORK AND OTHER PLACES YOU ARE LIKELY TO USE YOUR CHAIR); AND 3. YOUR NEED FOR OPTIONS FOR YOUR SAFETY AND COMFORT (SUCH AS ANTI-TIPPERS, POSITIONING BELTS OR SPECIAL SEATING SYSTEMS). IF YOU IGNORE THIS WARNING, YOU MAY ENDANGER YOUR HEALTH. I WARNING - TIE-DOWN RESTRAINTS TILITE RECOMMENDS that WHEELCHAIR USERS NOT BE transported IN VEHICLES OF ANY KIND WHILE IN WHEELCHAIRS. AS OF THIS date, THE UNITED States Department OF Transportation HAS NOT APPROVED ANY TIE-DOWN SYSTEM FOR transportation OF A USER WHILE IN A WHEELCHAIR IN A MOVING VEHICLE OF ANY TYPE. -

Badlands, Blank Space, Border Vacuums, Brown Fields, Conceptual Nevada, Dead Zones …

10 ISSN: 1755-068 www.field-journal.org vol.1 (1) …badlands, blank space, border vacuums, brown fields, conceptual Nevada, Dead Zones … 1 The term I have used to describe these …badlands, blank space, border vacuums, brown fields, spaces, which is reflected in all the conceptual Nevada, Dead Zones1, derelict areas,ellipsis other terms mentioned above, is ‘dead zone’. The term was taken directly spaces, empty places, free space liminal spaces, from the jargon of urban planners, and from a particular case of such space in ,nameless spaces, No Man’s Lands, polite spaces, , post Tel Aviv (cf. Gil Doron,‘Dead Zones, architectural zones, spaces of indeterminacy, spaces of Outdoor Rooms and the Possibility of Transgressive Urban Space’ in K. Franck uncertainty, smooth spaces, Tabula Rasa, Temporary and Q. Stevens (eds.), Loose Space: Autonomous Zones, terrain vague, urban deserts, Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life (New York: Routledge, 2006). The vacant lands, voids, white areas, Wasteland... SLOAPs term should be read in two ways: one with inverted commas, indicating my Gil M. Doron argument that an area or space cannot be dead or a void, tabula rasa etc. The second reading collapses the term in on itself – while the planners see a dead zone, I argue that it is not the area which If the model is to take every variety of form, then the matter in which the is dead but it is the zone, or zoning, and the assumption that whatever exists model is fashioned will not be duly prepared, unless it is formless, and (even death) in this supposedly delimited free from the impress of any of these shapes which it is hereafter to receive area always transcends the assumed from without.2 boundaries and can be found elsewhere. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74