A Collision of Gargoyles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1967 Gargoyle

the 1967 gargoyle The 1967 Gargoyle Flushing High School Flushing, New York Mr. Arthur Franzen, Principal • /875 ~~. Gargoyle Staff Editors-in-chief Edward Rauschkolb Bonnie Sherman Literary Editor Harriet Teller Art Editor Brenda Eskenazi Managing Editor Eileen Grossmar Photography Editor Kenneth Slovak Advertising Editor Lois Falk Faculty Adviser Mr. Milton Gordon Business Manager Mr, Morris Rosenblatt Evelyn Langlieb Photography Staff Literary Contributors Phyllis Schuster Walter Gross Ronald Bash Suzy Daytre Mike Hirschfeld Susan Kesner Steven Tischler Larry Herschaft DavId Nevis Sandie Feinman Henry Lenz Joan Friedwald Bruce Blaisdell Art Staff KatM Velten Clerical Staff Marlene Steiger Peter Simon Constance Ragone Freda Forman Rebecca Aiger Lynn Stekas Arlene Rubinstem Beth Schlau Carolyn Wells Paula Silverman Vivian Koffer Linda Singer Barbara Shana Shelley Drucker Ellen Busman Janet Silverman Freda Forman Pamela Glachman Carol Boltz Larissa Podgoretz Isa Bernstein Alan Perlman David Master Marlene Lamhut Debbie Baumann Deborah Singer Hettie Frank Gayle Fittipaldi Meryl Dorman Marilyn Roth 2 Table of Contents Principal's Message 4 Dedication 5 Departments 10 Extracurricular 25 Sports 34 The Graduates 43 Advertisers 97 I 3 Principal's Message The Gargoyle staff has chosen felicitous specialized so that the good fortune of success ly the device of quotations as hooks to hang in a career may be achieved. Success, in living. things on. My message to the seniors hangs of course. demands wider preparation. You on this hook, a quotation from Louis Pasteur: seniors have made a start in preparing your "Chance favors the prepared mind," That is. minds. Continue that preparation until all the prepared mind recognizes fortune. -

Gargoyles.Notebook February 24, 2016

gargoyles.notebook February 24, 2016 Bring in an image to art of something you want to create into a clay gargoyle. What is a gargoyle? Feb 211:03 PM 1 gargoyles.notebook February 24, 2016 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t3QUQS1ypPk The word "Gargoyle" shares a root with the word "Gargle"; they come from "gargouille," an old French word for "Throat." A true gargoyle is a waterspout. An unusual carved creature that does not serve that purpose is properly called a "Grotesque." Feb 152:42 PM 2 gargoyles.notebook February 24, 2016 Gargoyles can be traced back 4000 years to Egypt, Rome and Greece. Terra cotta water spouts depicting: lions, eagles, and other creatures, including those based on Greek and Roman mythology, were very common. Gargoyle water spouts were even found at the ruins of Pompeii. The first grotesque figures came from Egypt. The Egyptians believed in deities with the heads of animals and frequently replicated these deities in their architecture and wall paintings. Feb 152:54 PM 3 gargoyles.notebook February 24, 2016 Notre Dame Cathedral Paris, France Feb 152:59 PM 4 gargoyles.notebook February 24, 2016 NotreDame Cathedral Paris, France A prominent landmark NotreDame is a perfect example of Gothic architecture. The Construction of Notre Dame took 2 centuries and began in 1163 by Pope Alexander III and ended in 1345. http://www.fno.org/exhibits/Gargoyles/gargoyle.html Feb 1611:53 AM 5 gargoyles.notebook February 24, 2016 National Cathedral Washington, DC Feb 1611:57 AM 6 gargoyles.notebook February 24, 2016 Walter S. -

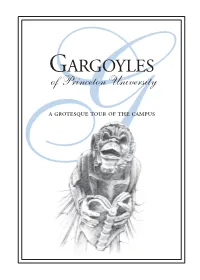

Gargoyles of Princeton University Ga Grotesque Tour of the Campus

GARGOYLES of Princeton University Ga grotesque tour of the campus 1 2 Here we were taught by men and Gothic towers democracy and faith and righteousness and love of unseen things that do not die. H. E. Mierow ’14 or centuries scholars have asked why gargoyles inhabit their most solemn churches and institutions. Fantastic explanations have come downF from the Middle Ages. Some art historians believe that gargoyles were meant to depict evil spirits over which the Christian church had triumphed. One theory suggests that these devils were frozen in stone as they fled the church. Supposedly, Christ set these spirits to work as useful examples to men instead of sending them straight to damnation. Others say they kept evil spirits away. Psychologists suggest that gargoyles represent the fears and superstitions of medieval men. As life became more secure, the gargoyles became more comical and whimsical. This little book introduces you to some men, women, and beasts you may have passed a hundred times on the campus but never noticed. It invites you to visit some old favorites. A pair of binoculars will bring you face-to-face with second- and third- story personalities. Why does Princeton have gargoyles and grotesques? Here is one excuse: … If the most fanciful and wildest sculptures were placed on the Gothic cathedrals, should they be out of place on the walls of a secular educational establishment? (“Princeton’s Gargoyles,” New York Sun, May 13, 1927) Note: Taking some technical license, the creatures and carvings described in this publication are referred to as “gargoyles” and “grotesques.” Typically, gargoyles are defined as such only when they also serve to convey water away from a building. -

Bible/Book Studies

1 BIBLE/BOOK STUDIES A Gospel for People on the Journey Luke Novalis Scripture Studies Series Each of the writers of the Gospels has his particular vision of Jesus. For Luke, Jesus is not only the one who announces the Good News of salvation: Jesus is our salvation. 9 copies Editor: Michael Trainor A Gospel for Searching People Matthew Novalis Scripture Studies Series Each of the writers of the Gospels has his particular vision of Jesus. For Matthew, Jesus is the great teacher (Matt. 23:8). But teacher and teachings are inextricable bound together, Matthew tells us. Jesus stands alone as unique teacher because of his special relationship with God: he alone is Son of man and Son of God. And Jesus still teaches those who are searching for meaning and purpose in life today. 9 copies Editor: Michael Trainor A Gospel for Struggling People Mark Novalis Scripture Studies Series “Who do you say that I am? In Mark’s Gospel, no one knows who Jesus is until, in Chapter 8, Peter answers: “You are the Christ.” But what does this mean? The rest of the Gospel shows what kind of Christ or Messiah Jesus is: he has come to suffer and die for his people. Teaching on discipleship and predictions of his death point ahead to the focus of the Gospel-the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus. 9 copies Editor: Michael Trainor Beautiful Bible Stories Beautiful Bible Stories by Rev. Charles P. Roney, D.D. and Rev. Wilfred G. Rice, Collaborator Designed to stimulate a greater interest in the Bible through the arrangement of extensive References, Suggestions for Study, and Test Questions. -

Gargoyles on Glatfelter Hall Katherine D

Hidden in Plain Sight Projects Hidden in Plain Sight Spring 2006 Gargoyles on Glatfelter Hall Katherine D. Anthony Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/hiddenpapers Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Anthony, Katherine D., "Gargoyles on Glatfelter Hall" (2006). Hidden in Plain Sight Projects. 3. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/hiddenpapers/3 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gargoyles on Glatfelter Hall Description When one walks around the campus of Gettysburg College, Glatfelter Hall towers above them, as one of the College’s most commanding edifices. One takes notice of the arched doorways, sunken windows, and the giant bell tower whose occupant chimes on the hour. What one may not notice are the eyes watching from the brownstone; faces and creatures at home in the stone, surveying your every move. Grotesques and gargoyles sit in the moldings, on the window sills and at the junction where roof and wall meet, hidden from the eye that does not have the compulsion to look. These architectural ornaments are not noticed outright because they tend to blend in with the stonework on the building. However, once you have seen them, you never cease to feel their eyes upon you. [excerpt] Course Information: • Course Title: HIST 300: Historical Method • Academic Term: Spring 2006 • Course Instructor: Dr. -

Prophetic Dreams and Visions Concerning the Church, Israel, and the Nations

Prophetic Dreams and Visions concerning the Church, Israel, and the Nations Eric Michael Teitelman Pastor•Teacher•Worship Leader Scripture References Scripture sources: NASB and NKJV Italic text represents scripture, interpretation, or commentary on the dream or vision. Job 33:14-18 “For God may speak in one way, or in another, yet man does not perceive it. In a dream, in a vision of the night, when deep sleep falls upon men, while slumbering on their beds, Then He opens the ears of men, and seals their instruction. In order to turn man from his deed, and conceal pride from man, He keeps back his soul from the Pit, and his life from perishing by the sword.” Exe 12:23-25 “But tell them, The days draw near as well as the fulfillment of every vision. For there will no longer be any false vision or flattering divination within the house of Israel. For I the LORD will speak, and whatever word I speak will be performed. It will no longer be delayed, for in your days, O rebellious house, I will speak the word and perform it, declares the Lord GOD.” Num 12:6 “He said, Hear now My words: If there is a prophet among you, I, the LORD, shall make Myself known to him in a vision. I shall speak with him in a dream.” Dan 1:17 “As for these four young men, God gave them knowledge and skill in all literature and wisdom; and Daniel had understanding in all visions and dreams.” Joe 2:28 “It will come about after this That I will pour out My Spirit on all mankind; And your sons and daughters will prophesy, Your old men will dream dreams, Your young men will see visions.” The Church, Israel, and the Nations thehouseofdavid.org Table of Contents 2004 ............................................................................................................................................................. -

To Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/805 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity VOLUME 2: MEDIEVAL MEETS MEDIEVALISM JAN M. ZIOLKOWSKI THE JUGGLER OF NOTRE DAME VOLUME 2 The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity Vol. 2: Medieval Meets Medievalism Jan M. Ziolkowski https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Jan M. Ziolkowski, The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. Volume 2: Medieval Meets Medievalism. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0143 Copyright and permissions for the reuse of many of the images included in this publication differ from the above. Copyright and permissions information for images is provided separately in the List of Illustrations. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

Introduction to Gothic Architecture and Gargoyles 6Th Grade Late Medieval & Gothic Art Gothic Era 1150/1400

Introduction to Gothic Architecture and Gargoyles 6th Grade Late Medieval & Gothic Art Gothic Era 1150/1400 about 250 years Gothic Gothic Architecture • Gothic architecture is a style of architecture that flourished during the high and late medieval period. It evolved from Romanesque architecture and was succeeded by Renaissance architecture. • Originating in 12th Century France and lasting into the 16th century, Gothic architecture was known during the period as "the French Style”. • The term Gothic first appeared during the Renaissance. • Its characteristic features include the pointed arch, the ribbed vault and the flying buttress. • Gothic architecture includes many of the great cathedrals, castles, palaces, town halls, universities, abbeys and parish churches of Europe. • A series of Gothic revivals began in mid-18th century England, spread through 19th-century Europe and continued into the 20th century. Ideal Gothic Church Notre Dame Cathedral begun in 1163 Notre Dame Cathedral flying buttresses c. 1175 Chartres Cathedral buttresses Flying Buttress diagram Other Gothic innovations • pointed arch (instead of round arch) • ribbed vault (instead of dome) • stained glass windows WHO CAME UP WITH THESE IDEAS? Abbey Church of Saint Denis ribbed vaulting Chartres V Cathedral E R T I C A L I T Y Chartres Cathedral detail Proportion – heads to bodies? Chartres Cathedral detail 1150 - a Gothic date to remember Gothic style architecture starts and is rapidly falls out of fashion around 1150. A much clearer start & style than Romanesque PLAGUE -

Travel & Landscape Wall

Travel & Landscape Wall Art CATALOGUE ViviennePHOTOGRACourPHY t England England E01 E02 E03 E19 E20 E21 Swanage Pier, Dorset Swanage Pier, Dorset Old Harry’s Rocks, Dorset London Eye, London London Eye Tower Bridge, London E04 E05 E06 E22 E23 E24 Swanage Beach, Dorset Swanage Beach, Dorset Swanage Beach, Dorset Bamburgh Castle Bamburgh Castle Bamburgh Castle E07 E08 E09 E25 E26 E27 Swanage Beach, Dorset Swanage Beach, Dorset Swanage Beach, Dorset Holy Island, Lindisfarne Fishermen’s Huts, Northumberland Country Fields E10 E11 E12 E28 E29 E30 Swanage Beach, Dorset Durdle Door Beach Bodiam Castle Boat House at Winkworth Bluebell Forest Lavendar Fields E13 E14 E15 E31 E32 E33 Corfe Castle, Dorset Corfe Castle, Dorset Corfe Castle, Dorset English Fields English Country English Fields E16 E17 E18 E34 E35 E36 Lake District Lake District Lake District York, England Roman Ruins, York Streets of York ©Vivienne Court | All Rights Reserved | [email protected] | 07967309090 ©Vivienne Court | All Rights Reserved | [email protected] | 07967309090 Wales Europe EU01 EU02 EU03 W01 W02 W03 Gargoyle, Paris Gargoyle, Paris Gargoyle, Paris Mumbles Lighthouse Blue Hour, Bracelet Bay Mumbles Lighthouse EU04 EU05 EU06 EU07 W04 W05 W06 Gargoyle1 Gargoyle2 Gargoyle3 Gargoyle4 Three Cliffs Bay Three Cliffs Bay Three Cliffs Bay EU08 EU09 EU10 W07 W08 W09 Notre Dame, Paris Windmill, France Tuscany, Italy Rhossili Bay Rhossili Bay Rhossili Bay EU11 EU12 EU13 Scotland S01 S02 S03 Florence, Italy Florence, Italy Ponte Vecchio, Florence EU14 EU15 EU16 Blue -

The Everlasting Man by G.K. Chesterton

The Everlasting Man by G.K. Chesterton Originally Published 1925 This book is in the Public Domain The Everlasting Man by G.K. Chesterton Prefatory Note........................................................................................................... 3 Introduction The Plan Of This Book .......................................................................... 3 Part I On the Creature Called Man.......................................................................... 10 I. The Man in the Cave .......................................................................................... 10 II. Professors and Prehistoric Men .......................................................................... 22 III. The Antiquity of Civilisation............................................................................. 32 IV. God and Comparative Religion...................................................................... 50 V. Man and Mythologies........................................................................................ 62 VI. The Demons and the Philosophers............................................................... 72 VII. The War of the Gods and Demons .............................................................. 86 VIII. The End of the World .................................................................................... 96 Part II On the Man Called Christ............................................................................ 106 I. The God in the Cave ....................................................................................... -

Glossary of Architectural Terms Arch Acurved Structure of Bricks Or Blocks Over an Opening

Glossary of Architectural Terms Arch Acurved structure of bricks or blocks over an opening. Architrave The lowest part of an entablature. Art Deco An architectural style popular during the 1920s and 1930s, derived from an exhibition of decorative arts in Paris, France in 1925. A simplified form of classical architecture using colourful geometric and naturalistic motifs. Sometimes called Jazz Moderne. Art Nouveau Astyle of decoration featuring curved lines and geometric and floral patterns. The name of a shop in Paris, France, opened in 1885, specializing in household objects. Balustrade Arailing supported by a series of ornamental posts or pillars that form a fence. Bay Window An angular or curved projection of an exterior wall that contains windows. Battleship Linoleum Flooring used between 1850 and 1950. So called because it was the material used for floors on U.S. battleships. Beaux Arts Style (Classicism) Aclassically derived architectural style that flourished between 1885 and 1920. Originated at the Ecole des Beaux – Arts in Paris, France. Emphasizes symmetry. Glossary of Architectural Terms Beveled Glass Glass that is cut with slopped edges. These edges dissect light creating prisms. Capital The decorative feature at the top of a column or pilaster. Classical Revival (Neo-Classical) Architectural style that mimics Greek or Roman styles. Column Round vertical supports for an arch or entablature. Consist of a base, a shaft and a capital. Corinthian Order The most elaborate of the three Greek orders (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian). Usually having a slender column, inverted bell-shaped capital with acanthus leaves and scrolls. Cornerstone Afoundation stone often with dates or builder(s) inscribed. -

'Medieval Gargoyles in Clay' – Tutor Tony

Young Masters – Week 13 class ‘Medieval Gargoyles In Clay’ – Tutor Tony Bullock • This lesson provides opportunities for students to create a gargoyle in clay while learning techniques for pinch/slab construction • Learn the functions of gargoyles from an Art History perspective • Learn about the significance and symbolism of gargoyles in Gothic architecture • Materials: sketching paper, pencils, clay, clay tools A gargoyle is a sculpture of imaginary beasts created during the Middle Ages as a part of Gothic architecture. The word “Gargoyle” comes from the French word “Gargouille” that means ‘Throat’ and describes a grotesque carved human or animal face. Gargoyles were located along the roof and downspouts on cathedral buildings. Their function was to drain the water away from the stone carvings on the buildings. Gargoyles have been used as architectural rain spouts since they adorned Temples in Greek and Roman times. However, as architecture progressed, these rainspouts became more and more ornate. They reached such a point that they were no longer functional and were called Grotesques. More familiar are the carved limestone fantasy creatures that topped European Medieval cathedrals in the 11th - 13th centuries, such as Notre Dame in Paris, France. They were created fierce and fantastic looking to serve a purpose of protecting and guarding role to scare away evil spirits. Medieval artists created their gargoyles based on animals they had observed, combining human and animal features, exaggerated characteristics like eyebrows, lips, and wrinkles, and used their imaginations to create creatures, which would inspire fear and obedience. .