Политичка Мисла Political Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 44. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Freitag, 27.Juni 2014 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 4 Entschließungsantrag der Abgeordneten Caren Lay, Eva Bulling-Schröter, Dr. Dietmar Bartsch, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. zu der dritten Beratung des Gesetzentwurfs der Bundesregierung Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur grundlegenden Reform des Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetzes und zur Änderung weiterer Bestimmungen des Energiewirtschaftsrechts - Drucksachen 18/1304, 18/1573, 18/1891 und 18/1901 - Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 575 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 56 Ja-Stimmen: 109 Nein-Stimmen: 465 Enthaltungen: 1 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 27.06.2014 Beginn: 10:58 Ende: 11:01 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Stephan Albani X Katrin Albsteiger X Peter Altmaier X Artur Auernhammer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Julia Bartz X Günter Baumann X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. Andre Berghegger X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Ute Bertram X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexandra Dinges-Dierig X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Jutta Eckenbach X Dr. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. -

Electoral Rules and Elite Recruitment: a Comparative Analysis of the Bundestag and the U.S

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 6-27-2014 Electoral Rules and Elite Recruitment: A Comparative Analysis of the Bundestag and the U.S. House of Representatives Murat Altuglu Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14071144 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Altuglu, Murat, "Electoral Rules and Elite Recruitment: A Comparative Analysis of the Bundestag and the U.S. House of Representatives" (2014). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1565. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1565 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida ELECTORAL RULES AND ELITE RECRUITMENT: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE BUNDESTAG AND THE U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Murat Altuglu 2014 To: Interim Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Murat Altuglu, and entitled Electoral Rules and Elite Recruitment: A Comparative Analysis of the Bundestag and the U.S. House of Representatives, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual -

Bund Entlastet Kommunen Und Stärkt Den Ausbau Der

Landesgruppe Nordrhein-Westfalen Nr. 21/04.12.2014 Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, Bund entlastet Kommunen und stärkt liebe Freunde, den Ausbau der Kindertagesbetreuung nach Vorlage des Gesetz- entwurfs zu Änderungen im Wasserhaushaltsgesetz be- Bereits in den vergangenen Legisla- züglich Fracking ist die un- turperioden hat der Bund Länder konventionelle Erdgasförde- und Kommunen umfassend entlas- rung erneut in den Mittel- tet. So wurde etwa mit der vollstän- punkt der Diskussion ge- rückt. digen Übernahme der laufenden In den beiden zurückliegenden Jahren habe ich Nettoausgaben für die Grundsiche- öffentlich stets meine klar ablehnende Haltung rung im Alter und bei Erwerbsmin- zu Fracking erklärt. Solange Restrisiken für derung bereits ein wesentlicher Bei- Mensch und Natur verbleiben, halte ich diese Technologie für nicht vertretbar. Es bestehen trag zur Verbesserung der kommu- zudem enorme Wissenslücken. Im vergangenen nalen Finanzsituation geleistet. Im Jahr konnte ich mit meinen CDU-Kollegen aus Jahr 2014 führt die letzte Stufe der Anhebung der Bundesbeteiligung von dem Münsterland, weiteren westfälischen 75 Prozent auf 100 Prozent zu einer Entlastung in Höhe von voraussicht- Kollegen und der bayerischen CSU darauf hinwirken, dass es erst gar nicht zur Vorlage lich rund 1,6 Milliarden Euro. Die Entlastung der Kommunen zählt auch eines entsprechenden Gesetzentwurfes kam. weiterhin zu den prioritären Maßnahmen des Bundes. Im Rahmen der Dem jetzt von den zuständigen Bundesminis- Verabschiedung des Bundesteilhabegesetzes sollen die Kommunen im tern Sigmar Gabriel und Dr. Barbara Hendricks Umfang von 5 Milliarden Euro jährlich von der Eingliederungshilfe entlas- vorliegenden Gesetzentwurf kann ich in dieser Form nur ablehnen. Ich habe sozusagen an tet werden. Bereits im Vorgriff darauf wird der Bund in den Jahren 2015 allen Infoveranstaltungen der letzten zwei Jahre bis 2017 die Kommunen in Höhe von 1 Milliarde Euro pro Jahr entlasten. -

16. Bundesversammlung Der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Berlin, 12

16. Bundesversammlung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Berlin, 12. Februar 2017 Gemeinsame Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages und des Bundesrates anlässlich der Eidesleistung des Bundespräsidenten Berlin, 22. März 2017 Inhalt 4 16. Bundesversammlung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 6 Rede des Präsidenten des Deutschen Bundestages, Prof. Dr. Norbert Lammert 16 Konstituierung der 16. Bundesversammlung 28 Bekanntgabe des Wahlergebnisses 34 Rede von Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier 40 Gemeinsame Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages und des Bundesrates anlässlich der Eidesleistung des Bundespräsidenten Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier 42 Programm 44 Begrüßung durch den Präsidenten des Deutschen Bundestages, Prof. Dr. Norbert Lammert 48 Ansprache der Präsidentin des Bundesrates, Malu Dreyer 54 Ansprache des Bundespräsidenten a. D., Joachim Gauck 62 Eidesleistung des Bundespräsidenten Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier 64 Ansprache des Bundespräsidenten Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier 16. Bundesversammlung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Berlin, 12. Februar 2017 Nehmen Sie bitte Platz. Sehr geehrter Herr Bundespräsident! Exzellenzen! Meine Damen und Herren! Ich begrüße Sie alle, die Mitglieder und Gäste, herzlich zur 16. Bundesversammlung im Reichstagsgebäude in Berlin, dem Sitz des Deutschen Bundestages. Ich freue mich über die Anwesenheit unseres früheren Bundesprä- sidenten Christian Wulff und des langjährigen österreichischen Bundespräsidenten Heinz Fischer. Seien Sie uns herzlich willkommen! Beifall Meine Damen und Herren, der 12. Februar ist in der Demokratiegeschichte unseres Landes kein auffälliger, aber eben auch kein beliebiger Tag. Heute vor genau 150 Jahren, am 12. Februar 1867, wurde ein Reichstag gewählt, nach einem in Deutschland nördlich der Mainlinie damals in jeder Hinsicht revolu- tionären, nämlich dem allgemeinen, gleichen Rede des Präsidenten des Deutschen Bundestages, Prof. Dr. Norbert Lammert 6 und direkten Wahlrecht. Der Urnengang zum konstituierenden Reichstag des Norddeut- schen Bundes stützte sich auf Vorarbeiten der bekannte. -

Afd Vor Dem Großen Sprung

: rer . 3 nde rt S wa ie Zu llab ko rlin Be Das Ostpreußenblatt Einzelverkaufspreis: 2,50 Euro Nr. 37 – 13. September 2014 C5524 - PVST. Gebühr bezahlt U NABHÄNGIGE W OCHENZEITUNG FÜR D EUTSCHLAND DIES E WOCH E JAN HEITMANN : Total verbockt Aktuell er als Zuwanderer dem Warnung vor den eigenen WStaat durch die illegale Be - Leuten setzung eines öffentlichen Plat - Ex-US-Geheimdienstler zes ein „Einigungspapier“ schreiben der Kanzlerin 2 abringt, erhält dadurch weder einen Aufenthaltstitel noch eine Duldung. Diese Entscheidung Preuße n/ Berlin des Berliner Verwaltungsgerichts ist zu begrüßen, macht sie doch Zuwanderer: Berlin deutlich, dass sich der Staat letzt - kollabiert endlich nicht nötigen lässt. Das Erstaufnahme wegen des Urteil hat aber einen negativen Ansturms geschlossen 3 Beigeschmack, denn wieder ein - mal musste die Justiz richten, was die Politik total verbockt Hintergrund hat. Richtig wäre es gewesen, wenn der Senat den Platz sofort Kränkelnd, aber nicht durch die Polizei hätte räumen schwach und die nicht asylberechtigten China als Gewinner der Personen abschieben lassen, Ukraine-Krise 4 statt dort über lange Zeit einen rechtsfreien Raum zu dulden. Vor der EZB in Frankfurt: Tausende AfD-Anhänger demonstrieren gegen die Europolitik Bild: action press Die mit den Besetzern erzielte Deutschland Einigung kommt einer Kapitula - tion des Rechtsstaates gleich. Sparen à la Schäuble Den ehemaligen Oranien - Bundesbehörden und AfD vor dem großen Sprung platz-Besetzern, die durch die Ei - Infrastruktur müssen nigung nur vermeintlich Rechte wegen Sparvorgaben leiden 5 erworben haben, stehen nun der Die Landtagswahlen diesen Sonntag werden Deutschland verändern Rechtsweg und die Anrufung von Petitionsausschüssen sowie Ausland Der Siegeszug der AfD erscheint nach dem Bruch mit der SPD oder men-Partei, hieß es lange. -

Abgeordnete Bundestag Ergebnisse

Recherche vom 27. September 2013 Abgeordnete mit Migrationshintergrund im 18. Deutschen Bundestag Recherche wurde am 15. Oktober 2013 aktualisiert WWW.MEDIENDIENST-INTEGRATION.DE Bundestagskandidaten mit Migrationshintergrund VIELFALT IM DEUTSCHEN BUNDESTAG ERGEBNISSE für die 18. Wahlperiode Im neuen Bundestag finden sich 37 Parlamentarier mit eigener Migrationserfahrung oder mindestens einem Elternteil, das eingewandert ist. Im Verhältnis zu den insgesamt 631 Sitzen im Parlament stammen somit 5,9 Prozent der Abgeordneten aus Einwandererfamilien. In der gesamten Bevölkerung liegt ihr Anteil mehr als dreimal so hoch, bei rund 19 Prozent. In der vorigen Legislaturperiode saßen im Bundestag noch 21 Abgeordnete aus den verschiedenen Parteien, denen statistisch ein Migrationshintergrund zugesprochen werden konnte. Im Vergleich zu den 622 Abgeordneten lag ihr Anteil damals lediglich bei 3,4 Prozent. Die Anzahl der Parlamentarier mit familiären Bezügen in die Türkei ist von fünf auf elf gestiegen. Mit Cemile Giousouf ist erstmals auch in der CDU eine Abgeordnete mit türkischen Wurzeln im Bundestag vertreten, ebenso wie erstmals zwei afrodeutsche Politiker im Parlament sitzen (Karamba Diaby, SPD und Charles M. Huber, CDU). Gemessen an der Anzahl ihrer Sitze im Parlament verzeichnen die LInken mit 12,5 Prozent und die Grünen mit 11,1 Prozent den höchsten Anteil von Abgeordneten mit Migrationshintergrund. Die SPD ist mit 13 Parlamentariern in reellen Zahlen Spitzenreiter, liegt jedoch im Verhältnis zur Gesamtzahl ihrer Abgeordneten (193) mit 6,7 -

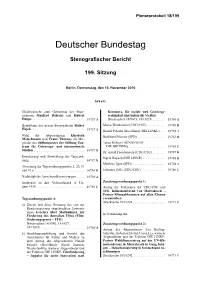

Plenarprotokoll 18/199

Plenarprotokoll 18/199 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 199. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 10. November 2016 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abge- Kommerz, für soziale und Genderge- ordneten Manfred Behrens und Hubert rechtigkeit und kulturelle Vielfalt Hüppe .............................. 19757 A Drucksachen 18/8073, 18/10218 ....... 19760 A Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Rainer Marco Wanderwitz (CDU/CSU) .......... 19760 B Hajek .............................. 19757 A Harald Petzold (Havelland) (DIE LINKE) .. 19762 A Wahl der Abgeordneten Elisabeth Burkhard Blienert (SPD) ................ 19763 B Motschmann und Franz Thönnes als Mit- glieder des Stiftungsrates der Stiftung Zen- Tabea Rößner (BÜNDNIS 90/ trum für Osteuropa- und internationale DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... 19765 C Studien ............................. 19757 B Dr. Astrid Freudenstein (CDU/CSU) ...... 19767 B Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Sigrid Hupach (DIE LINKE) ............ 19768 B nung. 19757 B Matthias Ilgen (SPD) .................. 19769 A Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 5, 20, 31 und 41 a ............................. 19758 D Johannes Selle (CDU/CSU) ............. 19769 C Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen ... 19759 A Gedenken an den Volksaufstand in Un- Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: garn 1956 ........................... 19759 C Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD: Klimakonferenz von Marrakesch – Pariser Klimaabkommen auf allen Ebenen Tagesordnungspunkt 4: vorantreiben Drucksache 18/10238 .................. 19771 C a) -

Geschäftsbericht Der CDU-Bundesgeschäftsstelle

Bericht der Bundesgeschäftsstelle Anlage zum Bericht des Generalsekretärs 29. Parteitag der CDU Deutschlands · 5. – 7. Dezember 2016 · Messe Essen Geschäftsbericht der CDU-Bundesgeschäftsstelle Vorwort Die Ausgangslage für das Wahljahr 2017 ist gut, denn die Bilanz der CDU-geführten Bundesregierung kann sich sehen lassen: stabiles Wachstum, solide Finanzen, niedrige Arbeits- losigkeit und Investitionen in Bildung, Forschung, Straßen, Schienen sowie schnelles Internet. Unter der Überschrift „Wir bringen das Land voran!“ hat die CDU Deutschlands in den zurückliegenden Monaten diese erfolgreiche Bilanz dargestellt. Dies allein reicht jedoch nicht aus. Wir müssen den Wähle- rinnen und Wählern deutlich machen, warum wir sie darum bitten, uns für weitere Jahre ihr Vertrauen zu schenken. Deshalb haben wir gemeinsam mit der CSU sechs Deutsch- landkongresse durchgeführt zu den großen Herausforderungen unserer Zeit: Wir haben zusammen mit Experten und vielen Parteimitgliedern beispielsweise über unseren Zusammen- halt, die Frage der Sicherheit, über Ressourcenknappheit, Digitalisierung, Europa und Migration gesprochen. Wir stel- len uns diesen Zukunftsthemen, weil sie entscheidend dafür sind, dass wir in Deutschland weiter erfolgreich wirtschaften, arbeiten und leben können. In diesem Bewusstsein haben wir mit unseren Landesverbänden auf den Regionalkonferenzen diskutiert. Und dieses Verständnis prägt den vorliegenden Antrag „Orientierung in schwierigen Zeiten – für ein erfolg- reiches Deutschland und Europa“ des Bundesvorstands zum Parteitag. Dieser Antrag beschreibt den Rahmen und die Grundsätze für unser gemeinsames Wahlprogramm, das wir im Frühjahr Geschäftsbericht der CDU-Bundesgeschäftsstelle mit den Mitgliedern von CDU und CSU sowie den Bürge- rinnen und Bürgern in einem offenen Prozess diskutieren und danach verabschieden wollen. Unser 29. Parteitag in Essen ist damit eine wichtige Wegmarke. Das gilt für die Wahl zum neuen Deutschen Bundestag ebenso wie für die Land- tagswahlen im Saarland, in Schleswig-Holstein und in Nord- rhein-Westfalen. -

Gruppe Der Frauen Ausgabe 1 | 08

Gruppe der Frauen Ausgabe 1 | 08. Juli 2015 Liebe Leserinnen, in der Gruppe der Frauen hat sich vieles getan: Wir sind so ihre Vorstände und die obersten Führungsetagen eine groß wie nie und stellen jetzt ein Viertel unserer ganzen selbst gesetzte Zielvorgabe festlegen. Damit der Bund Fraktion! Viele unserer Kolleginnen haben neue Aufgaben nicht nur Forderungen an die Wirtschaft stellt, haben wir übernommen, Führungspositionen in unserer Fraktion das Bundesgleichstellungsgesetz und das Bundes- oder in Regierungsämtern. Unsere Vorsitzende der letzten gremienbesetzungsgesetz novelliert. Hier bleibt noch Legislaturperiode, Rita Pawelski, ist nach elf Jahren leider einiges an Umsetzung zu tun. nicht mehr zur Wahl um ein Bundestagsmandat angetre- ten. Wir haben deswegen im Dezember einen neuen Vor- Über einige unserer laufenden Arbeitsschwerpunkte stand gewählt. Neben Daniela Ludwig als Erster Stellver- erfahren Sie auf den folgenden Seiten mehr. So wollen tretenden Vorsitzenden, Elisabeth Winkelmeier-Becker, wir endlich wirksame gesetzliche Verbesserungen für Katharina Landgraf und Nadine Schön wurden Dr. Claudia Frauen (und wenige Männer) erreichen, die in der Lücking-Michel und Barbara Lanzinger in den Vorstand Prostitution tätig sind und dem kriminellen Handeln gewählt. Ich selbst als neue Vorsitzende freue mich über derer, die an Menschenhandel und Zwangsprostituti- einen breiten Vertrauensvorschuss, den mir meine Kolle- on verdienen, Einhalt gebieten. Ein weiteres wichtiges ginnen entgegengebracht haben. Ziel bleibt die Entgeltgleichheit -

Wahlkreisbewerber/Innen Der CDU Nordrhein-Westfalen Zur Bundestagswahl 2013

Düsseldorf, 4. März 2013 Wahlkreisbewerber/innen der CDU Nordrhein-Westfalen zur Bundestagswahl 2013 WK# Wahlkreis Bewerber/in 87 Aachen I Rudolf Henke 88 Aachen II Helmut Brandt 89 Heinsberg Wilfried Oellers 90 Düren Thomas Rachel 91 Rhein-Erft-Kreis I Dr. Georg Kippels 92 Euskirchen – Rhein-Erft-Kreis II Detlef Seif 93 Köln I Karsten Möring 94 Köln II Prof. Dr. Heribert Hirte 95 Köln III Gisela Manderla 96 Bonn Dr. Claudia Lücking-Michel 97 Rhein-Sieg-Kreis I Elisabeth Winkelmeier-Becker 98 Rhein-Sieg-Kreis II Dr. Norbert Röttgen 99 Oberbergischer Kreis Klaus-Peter Flosbach 100 Rheinisch-Bergischer Kreis Wolfgang Bosbach 101 Leverkusen – Köln IV Helmut Nowak 102 Wuppertal I Peter Hintze 103 Solingen – Remscheid – Wuppertal II Jürgen Hardt 104 Mettmann I Michaela Noll 105 Mettmann II Peter Beyer 106 Düsseldorf I Thomas Jarzombek 107 Düsseldorf II Sylvia Pantel 108 Neuss I Hermann Gröhe 109 Mönchengladbach Dr. Günter Krings 110 Krefeld I – Neuss II Ansgar Heveling 111 Viersen Uwe Schummer 112 Kleve Ronald Pofalla 113 Wesel I Sabine Weiss 114 Krefeld II – Wesel II Kerstin Radomski 115 Duisburg I Thomas Mahlberg 116 Duisburg II Volker Mosblech 117 Oberhausen – Wesel III Marie-Luise Dött Seite 1/2 WK# Wahlkreis Bewerber/in 118 Mülheim – Essen I Astrid Timmermann-Fechter 119 Essen II Jutta Eckenbach 120 Essen III Matthias Hauer 121 Recklinghausen I Philipp Mißfelder 122 Recklinghausen II Rita Stockhofe 123 Gelsenkirchen Oliver Wittke 124 Steinfurt I – Borken I Jens Spahn 125 Bottrop – Recklinghausen III Sven Volmering 126 Borken II Johannes Röring 127 Coesfeld – Steinfurt II Karl Schiewerling 128 Steinfurt III Anja Karliczek 129 Münster Sybille Benning 130 Warendorf Reinhold Sendker 131 Gütersloh I Ralph Brinkhaus 132 Bielefeld – Gütersloh II Lena Strothmann 133 Herford – Minden-Lübbecke II Dr. -

Berufliche Bildung Zukunftssicher Gestalten – Wettbewerbsfähigkeit Und Beschäftigung Stärken

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 18/1451 18. Wahlperiode 20.05.2014 Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Thomas Feist, Uda Heller, Albert Rupprecht, Michael Kretschmer, Stephan Albani, Katrin Albsteiger, Artur Auernhammer, Julia Bartz, Sybille Benning, Dr. André Berghegger, Dr. Christoph Bergner, Klaus Brähmig, Helmut Brandt, Cajus Caesar, Alexandra Dinges-Dierig, Thomas Dörflinger, Dr. Bernd Fabritius, Dr. Maria Flachsbarth, Dr. Hans-Peter Friedrich, Ingo Gädechens, Dr. Thomas Gebhart, Alois Gerig, Eberhard Gienger, Cemile Giousouf, Michael Grosse-Brömer, Astrid Grotelüschen, Fritz Güntzler, Helmut Heiderich, Franz-Josef Holzenkamp, Anette Hübinger, Xaver Jung, Dr. Stefan Kaufmann, Roderich Kiesewetter, Axel Knörig, Hartmut Koschyk, Gunther Krichbaum, Katharina Landgraf, Dr. Katja Leikert, Dr. Philipp Lengsfeld, Ingbert Liebing, Patricia Lips, Dr. Claudia Lücking-Michel, Yvonne Magwas, Matern von Marschall, Maria Michalk, Dr. Mathias Middelberg, Phillipp Mißfelder, Dietrich Monstadt, Marlene Mortler, Dr. Philipp Murmann, Josef Rief, Erwin Rüddel, Tankred Schipanski, Uwe Schummer, Johannes Selle, Bernd Siebert, Carola Stauche, Dr. Frank Steffel, Dr. Wolfgang Stefinger, Dieter Stier, Stephan Stracke, Max Straubinger, Matthäus Strebl, Lena Strothmann, Dr. Volker Ullrich, Volkmar Vogel (Kleinsaara), Sven Volmering, Christel Voßbeck-Kayser, Marco Wanderwitz, Marian Wendt, Heinz Wiese (Ehingen), Dagmar G. Wöhrl, Tobias Zech, Heinrich Zertik, Dr. Matthias Zimmer, Volker Kauder, Gerda Hasselfeldt und der Fraktion der CDU/CSU sowie der Abgeordneten Willi Brase, Rainer Spiering, Dr. Ernst Dieter Rossmann, Hubertus Heil (Peine), Edelgard Bulmahn, Dr. Daniela De Ridder, Dr. Karamba Diaby, Saskia Esken, Oliver Kaczmarek, Gabriele Katzmarek, Christine Lambrecht, Dr. Simone Raatz, Martin Rabanus, René Röspel, Marianne Schieder, Swen Schulz (Spandau), Thomas Oppermann und der Fraktion der SPD Berufliche Bildung zukunftssicher gestalten – Wettbewerbsfähigkeit und Beschäftigung stärken Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: I. -

Steinbrücklässtsichnichtverbiegen

Seite 3 NR. 65, MONTAG, 18. MÄRZ 2013 Steinbrücklässtsichnichtverbiegen NRW-SPD kürt Spitzenkandidaten auf Landesdelegiertenkonferenz in Bielefeld / Kraft verspricht Unterstützung Zitatdes Tages n einem halben Jahr, am feln ist Ruh.“ Was bleibe, sei das »Allewarten auf I22. September, ist Bundes- Geräusch von ablaufendem Ba- denFrühling – und tagswahl. Die NRW-SPD hat dewasser. „Blubb, blubb, alles ist weg.“ Etikettenschwindel bei stattdessenist da in Bielefeld ihre Landesliste Wahlversprechen wirft Stein- zusammengestellt. Inklusive brück der CDU/CSU vor. Die ›Andreas‹.« Peer-Show. Lohnuntergrenze, die Lebens- EineExpertindes Deutschen leistungsrente, Eigenheimzu- WetterdienstesinOffenbach lage und Familiensplitting seien überdie vonTiefdruckgebiet schöne Worte, aber vor allem „Andreas“bestimmtenWet- VON JULIA GESEMANN heiße Luft. Gleichgeschlechtli- teraussichten che Partnerschaften bräuchten ¥ Bielefeld. Aufder Landesdele- ein modernes Gesetz und nicht giertenkonferenz in der Stadt- das Weltbild der 50er Jahre, Zahl des Tages halle Bielefeld wählt die nord- „mit Gummibaum, Nierentisch rhein-westfälische SPD Peer undSalzstangen“. Steinbrück mit einem überra- Inder Schlusskurvekommt er 33 genden Ergebnis zum Spitzen- noch einmal richtig in Fahrt. Prozent kandidaten. 386 von 395 Stim- FaireBezahlung,gesetzlicher flä- men bekommt er. Eine Quote chendeckenderMindestlohn, Al- wenigerHerzinfarkte inner- von 97,92 Prozent. Die Genos- tersversorgung, bezahlbarer halbvon dreiJahren: Dasist sen zeigen Geschlossenheit. To- Wohnraum,angemessene