China's Airline Deregulation Since 1997 and the Driving Forces Behind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHOULD GOVERNMENTS LEASE THEIR AIRPORTS? by Robert W

SHOULD GOVERNMENTS LEASE THEIR AIRPORTS? by Robert W. Poole, Jr. August 2021 Reason Foundation’s mission is to advance a free society by developing, applying and promoting libertarian principles, including individual liberty, free markets and the rule of law. We use journalism and public policy research to influence the frameworks and actions of policymakers, journalists and opinion leaders. Reason Foundation’s nonpartisan public policy research promotes choice, competition and a dynamic market economy as the foundation for human dignity and progress. Reason produces rigorous, peer- reviewed research and directly engages the policy process, seeking strategies that emphasize cooperation, flexibility, local knowledge and results. Through practical and innovative approaches to complex problems, Reason seeks to change the way people think about issues, and promote policies that allow and encourage individuals and voluntary institutions to flourish. Reason Foundation is a tax-exempt research and education organization as defined under IRS code 501(c)(3). Reason Foundation is supported by voluntary contributions from individuals, foundations and corporations. The views are those of the author, not necessarily those of Reason Foundation or its trustees. SHOULD GOVERNMENTS LEASE THEIR AIRPORTS? i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Covid-19 recession has put new fiscal stress on state and local governments. One tool that may help them cope is called “asset monetization,” sometimes referred to as “infrastructure asset recycling.” As practiced by Australia and a handful of U.S. jurisdictions, the concept is for a government to sell or lease revenue-producing assets, unlocking their asset values to be used for other high-priority public purposes. This study focuses on the potential of large and medium hub airports as candidates for this kind of monetization. -

Transportation Information

Transportation Information The main airport in Shenyang is the Shenyang Airport (SHE) is the largest airport of northeast China offering direct flights to cities around China including countries such as Japan, Russia, and Korea Here are some of airlines out of Shenyang: ANA: +1 800 235 9262; http://www.fly-ana.com Asiana Airlines: +1 888 437 7718; http://www.flyasiana.com China Northern Airlines: +86 23 197 188; http://www.cna.com.cn/Eng/index-en.html China Southern Airlines: +86 20 950 333; http://www.cs-air.com/en/index.asp By plane The city is served by the Shenyang Taoxian International Airport (沈阳桃仙国际机场, airport code SHE), as well as by several smaller, regional airports. Direct flights from Shenyang go to Beijing, Changsha, Chaoyang, Chengdu, Chongqing, Dalian, Fuzhou, Guangzhou, Haikou, Hangzhou, Harbin, Hefei, Hong Kong, Jinan, Kunming, Lanzhou, Nanjing, Ningbo, Qingdao, Qiqihar, Sanya, Shanghai, Shantou, Shenzhen, Shijiazhuang, Taiyuan, Tianjin, wuromqi, Wenzhou, Wuhan, Xiamen, Xian, Xuzhou, Yanji, Yantai, Zahuang, Zhengzhou, and Zhuhai. Direct international flights go to Seoul and Cheongju, South Korea; Pyongyang, North Korea; Irkutsk and Khabarovsk, Russia; Osaka and Tokyo, Japan with connections to Frankfurt, Germany, Sydney, Australia, Los Angeles, USA and other cities. The airport is located 30 km south of the city. An airport shuttle runs from the airport to the main China Northern Airlines ticket office (Zhonghua Lu 117) and back frequently. By car Shenyang is connected by a major expressway, the Jing-shen 6-lane Expressway, to the city of Beijing, some 658 kilometers away. Expressways also link Shenyang with Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces. -

Industrial Reform and Air Transport Development in China

INDUSTRIAL REFORM AND AIR TRANSPORT DEVELOPMENT IN CHINA Anming Zhang Department of Economics University of Victoria Victoria, BC Canada and Visiting Professor, 1996-98 Department of Economics and Finance City University of Hong Kong Hong Kong Occasional Paper #17 November 1997 Table of Contents Abstract ..................................................................... i Acknowledgements ............................................................ i I. INTRODUCTION .........................................................1 II. INDUSTRIAL REFORM ....................................................3 III. REFORMS IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY .....................................5 IV. AIR TRANSPORT DEVELOPMENT AND COMPETITION .......................7 A. Air Traffic Growth and Route Development ................................7 B. Market Structure and Route Concentration ................................10 C. Airline Operation and Competition ......................................13 V. CONCLUDING REMARKS ................................................16 References ..................................................................17 List of Tables Table 1: Model Split in Non-Urban Transport in China ................................2 Table 2: Traffic Volume in China's Airline Industry ...................................8 Table 3: Number of City-pair Routes in China's Airline Industry .........................8 Table 4: Overview of Chinese Airline Performance, 1980-94 ............................9 Table 5: Traffic Performed by China's Airlines -

Air China Limited

Air China Limited Air China Limited Stock code: 00753 Hong Kong 601111 Shanghai AIRC London Annual Report 20 No. 30, Tianzhu Road, Airport Industrial Zone, Shunyi District, Beijing, 101312, P.R. China Tel 86-10-61462560 Fax 86-10-61462805 19 Annual Report 2019 www.airchina.com.cn 中國國際航空股份有限公司 (short name: 中國國航) (English name: travel experience and help passengers to stay safe by upholding the Air China Limited, short name: Air China) is the only national spirit of phoenix of being a practitioner, promoter and leader for the flag carrier of China. development of the Chinese civil aviation industry. The Company is also committed to leading the industrial development by establishing As the old saying goes, “Phoenix, a bird symbolizing benevolence” itself as a “National Brand”, at the same time pursuing outstanding and “The whole world will be at peace once a phoenix reveals performance through innovative and excelling efforts. itself”. The corporate logo of Air China is composed of an artistic phoenix figure, the Chinese characters of “中國國際航空公司” in Air China was listed on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited calligraphy written by Mr. Deng Xiaoping, by whom the China’s (stock code: 0753) and the London Stock Exchange (stock code: reform and opening-up blueprint was designed, and the characters of AIRC) on 15 December 2004, and was listed on the Shanghai Stock “AIR CHINA” in English. Signifying good auspices in the ancient Exchange (stock code: 601111) on 18 August 2006. Chinese legends, phoenix is the king of all birds. It “flies from the eastern Happy Land and travels over mountains and seas and Headquartered in Beijing, Air China has set up branches in Southwest bestows luck and happiness upon all parts of the world”. -

WORLD-CLASS Hospitality with Eastern Charm 世界品位 東方魅力 中國東方航空股份有限公司

CHINA EASTERN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIMITED AIRLINES CORPORATION CHINA EASTERN WORLD-CLASS Hospitality WITH Eastern Charm 世界品位 東方魅力 中國東方航空股份有限公司 ANNUAL REPORT 2013 年報 ANNUAL REPORT 2013 ANNUAL 年報 www.ceair.com (A joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (在中華人民共和國註冊成立的股份有限公司) (Stock Code 股份代號: 00670) Contents 2 Definitions 4 Financial Highlights (prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards) 5 Summary of Accounting and Business Data (prepared in accordance with PRC Accounting Standards) 6 Summary of Selected Operating Data 8 Fleet 10 Milestones 12 Chairman’s Statement 18 Review of Operations and Management’s Discussion and Analysis 27 Report of Directors 54 Corporate Governance 70 Report of the Supervisory Committee 72 Social Responsibilities 74 Financial Statements prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards • Independent Auditors’ Report • Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income • Consolidated Statement of Financial Position • Company’s Statement of Financial Position • Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows • Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity • Notes of the Financial Statements 170 Supplementary Financial Information 173 Corporate Information 002 China Eastern Airlines Definitions Corporation Limited Annual Report 2013 In this report, unless the context otherwise requires, the following expressions have the following meanings: AFTK the number of tonnes of capacity available for the carriage -

China Eastern Airlines Corporation Limited ANNUAL REPORT 2018 M O C Ceair

China Eastern Airlines Corporation Limited www . ceair. c o m AN N UAL REPORT 2 01 8 Stock Code : A Share : 600115 H Share : 00670 ADR : CEA A joint stock limited company incorporated in the People's Republic of China with limited liability Contents 2 Defi nitions 98 Report of the Supervisory Committee 5 Company Introduction 100 Social Responsibilities 6 Company Profi le 105 Financial Statements prepared in 8 Financial Highlights (Prepared in accordance with International accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards Financial Reporting Standards) • Independent Auditor’s Report 9 Summary of Accounting and Business • Consolidated Statement of Profi t Data (Prepared in accordance with or Loss and Other PRC Accounting Standards) Comprehensive Income 10 Summary of Major Operating Data • Consolidated Statement of Financial 13 Fleet Structure Position 16 Milestones 2018 • Consolidated Statement of Changes 20 Chairman’s Statement in Equity 30 Review of Operations and • Consolidated Statement of Cash Management’s Discussion and Flows Analysis • Notes to the Financial Statements 53 Report of the Directors 232 Supplementary Financial Information 79 Corporate Governance Defi nitions In this report, unless the context otherwise requires, the following expressions have the following meanings: AFK means Air France-KLM, a connected person of the Company under the Shanghai Listing Rules Articles means the articles of association of the Company Available freight tonne-kilometres means the sum of the maximum tonnes of capacity available for the -

Program Information China Eastern Airlines Corporation Limited

Program Information China Eastern Airlines Corporation Limited PROGRAM INFORMATION Type of Information: Program Information Date of Announcement: 2 February 2018 Issuer Name : China Eastern Airlines Corporation Limited Name and Title of Representative: Ma Xulun President and Vice Chairman Address of Head Office: Kong Gang San Road, Number 92 Shanghai, 200335 People’s Republic of China Telephone: +8621 6268 -6268 Contact Person : Attorney -in -Fact: Seishi Ikeda , Attorney -at -law Hiroki Watanabe, Attorney-at-law Baker & McKenzie (Gaikokuho Joint Enterprise) Address: Ark Hills Sengokuyama Mori Tower, 28th Floor 9-10, Roppongi 1-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan Telephone: +81-3-6271-9900 Type of Securities: Bond s Scheduled Issuance Period: 2 February 2018 to 1 February 2019 Maximum Outstanding Issuance Amount: JPY 50 billion Address of Website for Announcement : http://www.jpx.co.jp/equities/products/tpbm/announceme nt/index.html Status of Submission of Annual Securities Reports or None Issuer Filing Information: Name of the (Joint ) Lead Manager (s) (for the purpose Joint Lead Manager s for Guaranteed Bonds: of this Program Information) SMBC Nikko Capital Markets Limited DBJ Securities Co. Ltd. Joint Lead Managers for ICBC LC Bonds and BOC LC Bonds: Bank of China Limited Mizuho Securities Asia Limited SMBC Nikko Capital Markets Limited Daiwa Capital Markets Singapore Limited Morgan Stanley & Co. International plc Nomura International plc Notes to Investors: 1. TOKYO PRO -BOND Market is a market for professional investor s, etc. (Tokutei Toushika tou ) as defined in Article 2, Paragraph 3, Item 2(b)(2) of the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act of Japan (Law No. -

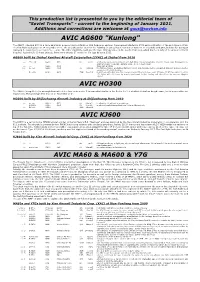

AVIC AG600 "Kunlong"

This production list is presented to you by the editorial team of "Soviet Transports" - current to the beginning of January 2021. Additions and corrections are welcome at [email protected] AVIC AG600 "Kunlong" The AG600 (Jiaolong 600) is a large amphibian powered by four Zhuzhou WJ6 turboprop engines. Development started in 2009 and construction of the prototype in 2014. The first flight took place on 24 December 2017. The aircraft can be used for fire-fighting (it can collect 12 tonnes of water in 20 seconds) and SAR, but also for transport (carrying 50 passengers over up to 5,000 km). The latter capability could give the type strategic value in the South China Sea, which has been subject to various territorial disputes. According to Chinese sources, there were already 17 orders for the type by early 2015. AG600 built by Zhuhai Yanzhou Aircraft Corporation (ZYAC) at Zhuhai from 2016 --- 'B-002A' AG600 AVIC ph. nov20 a full-scale mock-up; in white c/s with dark blue trim and grey belly, titles in Chinese only; displayed in the Jingmen Aviator Town (N30.984289 E112.087750), seen nov20 --- --- AG600 AVIC static test airframe 001 no reg AG600 AVIC r/o 23jul16 the first prototype; production started in 2014, mid-fuselage section completed 29dec14 and nose section completed 17mar15; in primer B-002A AG600 AVIC ZUH 30oct16 in white c/s with dark blue trim and grey belly, titles in Chinese only; f/f 24dec17; f/f from water 20oct18; 172 flights with 308 hours by may20; performed its first landing and take-off on the sea near Qingdao 26jul20 AVIC HO300 The HO300 (Seagull 300) is an amphibian with either four or six seats. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2007 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 45 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 48 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 51 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 58 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 62 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2007 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member BoD Board of Directors Cdr. Commander CEO Chief Executive Officer Chp. Chairperson COO Chief Operating Officer CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep.Cdr. Deputy Commander Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson Hon.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Soaring to New Heights in the Greater Bay Area: Opportunities and Market Potentials for the Aviation Industry Content 1

Soaring to new heights in the Greater Bay Area: Opportunities and market potentials for the aviation industry Content 1. Strengths of the aviation industry in the Greater Bay Area 3 from a macro perspective 2. Optimise airport infrastructures to scale the development of the industry 5 3. Cultivate growth of related industries through marketisation of airlines 9 4. Achieve efficient allocation of aviation resources through a comprehensive 12 transportation system 5. Logistics capacity as a growth enabler for aviation leasing 14 Conclusion 17 Contact us 18 Soaring to new heights in the Greater Bay Area: Opportunities and market potentials for the aviation industry 2 1. Strengths of the aviation industry in the Greater Bay Area from a macro perspective Soaring to new heights in the Greater Bay Area: Opportunities and market potentials for the aviation industry 3 1. Strengths of the aviation industry in the GBA from a macro perspective In February 2019, the Central Committee of the The Greater Bay Area is a hub that integrates Communist Party of China and the State Council manufacturing, technology and financial services – officially published the “Outline Development Plan for incorporating the strategic positioning of the other three the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area”. global Bay Areas. The Guangdong province has been a It stated clearly the national-level strategic plan for major manufacturing cluster since China’s economic developing the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater reform and opening-up, with Dongguan and Foshan Bay Area (hereinafter referred to as Greater Bay Area renowned for being the centre of world-class or GBA for short), with the aim to position it as one of manufacturing “world’s factory” in particular. -

Chairman's Statement

6 Chairman’s Statement Opportunities from industry-wide restructuring being closely explored to gain benefits of scale China Southern Airlines Company Limited Chairman’s Statement 7 Dear Shareholders: I am pleased to report the Group’s financial and operating results for 2000. Net profit attributable to shareholders was RMB502 million in 2000, representing an increase of 509% as compared with RMB82 million in 1999 notwithstanding the unfavourable operating environment faced by the Group as a result of inflated fuel prices. During 2000, with the Asian economies on their course of recovery, and the PRC economy gradually picking up under a series of positive financial and monetary policies, demand for aviation services was on the rise. Such demand was Yan Zhi Qing particularly keen during holidays, including the Chinese New Chairman of the Board of Directors Year, the Labor Day and the National Day. Amid the improved market environment, the Group experienced increases in load factors and aircraft utilisation rate during Such transactions not only helped expand the Group’s the period. As a result, the passenger revenue increased domestic route network, but also gave a boost to the from RMB11,819 million in 1999 to RMB13,255 million in operation efficiency and market share of the Group in the 2000. However, the Group’s operating profit was reduced area. In future, the Group will continue to explore business as the Group’s operation was under tremendous pressure opportunities arising from the Merger and Restructuring in due to high fuel prices. pursuit of economies of scale. The Group managed to achieve its cost control targets. -

Airlines Codes

Airlines codes Sorted by Airlines Sorted by Code Airline Code Airline Code Aces VX Deutsche Bahn AG 2A Action Airlines XQ Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Acvilla Air WZ Denim Air 2D ADA Air ZY Ireland Airways 2E Adria Airways JP Frontier Flying Service 2F Aea International Pte 7X Debonair Airways 2G AER Lingus Limited EI European Airlines 2H Aero Asia International E4 Air Burkina 2J Aero California JR Kitty Hawk Airlines Inc 2K Aero Continente N6 Karlog Air 2L Aero Costa Rica Acori ML Moldavian Airlines 2M Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Haiti Aviation 2N Aero Lloyd Flugreisen YP Air Philippines Corp 2P Aero Service 5R Millenium Air Corp 2Q Aero Services Executive W4 Island Express 2S Aero Zambia Z9 Canada Three Thousand 2T Aerocaribe QA Western Pacific Air 2U Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Amtrak 2V Aeroejecutivo SA de CV SX Pacific Midland Airlines 2W Aeroflot Russian SU Helenair Corporation Ltd 2Y Aeroleasing SA FP Changan Airlines 2Z Aeroline Gmbh 7E Mafira Air 3A Aerolineas Argentinas AR Avior 3B Aerolineas Dominicanas YU Corporate Express Airline 3C Aerolineas Internacional N2 Palair Macedonian Air 3D Aerolineas Paraguayas A8 Northwestern Air Lease 3E Aerolineas Santo Domingo EX Air Inuit Ltd 3H Aeromar Airlines VW Air Alliance 3J Aeromexico AM Tatonduk Flying Service 3K Aeromexpress QO Gulfstream International 3M Aeronautica de Cancun RE Air Urga 3N Aeroperlas WL Georgian Airlines 3P Aeroperu PL China Yunnan Airlines 3Q Aeropostal Alas VH Avia Air Nv 3R Aerorepublica P5 Shuswap Air 3S Aerosanta Airlines UJ Turan Air Airline Company 3T Aeroservicios