Battlefields Registration Selection Guide Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grenville Research

David & Jenny Carter Nimrod Research Docton Court 2 Myrtle Street Appledore Bideford North Devon EX39 1PH www.nimrodresearch.co.uk [email protected] GRENVILLE RESEARCH This report has been produced to accompany the Historical Research and Statement of Significance Reports into Nos. 1 to 5 Bridge Street, Bideford. It should be noted however, that the connection with the GRENVILLE family has at present only been suggested in terms of Nos. 1, 2 and 3 Bridge Street. I am indebted to Andy Powell for locating many of the reference sources referred to below, and in providing valuable historical assistance to progress this research to its conclusions. In the main Statement of Significance Report, the history of the buildings was researched as far as possible in an attempt to assess their Heritage Value, with a view to the owners making a decision on the future of these historic Bideford properties. I hope that this will be of assistance in this respect. David Carter Contents: Executive Summary - - - - - - 2 Who were the GRENVILLE family? - - - - 3 The early GRENVILLEs in Bideford - - - - 12 Buckland Abbey - - - - - - - 17 Biography of Sir Richard GRENVILLE - - - - 18 The Birthplace of Sir Richard GRENVILLE - - - - 22 1585: Sir Richard GRENVILLE builds a new house at Bideford - 26 Where was GRENVILLE’s house on The Quay? - - - 29 The Overmantle - - - - - - 40 How extensive were the Bridge Street Manor Lands? - - 46 Coat of Arms - - - - - - - 51 The MEREDITH connection - - - - - 53 Conclusions - - - - - - - 58 Appendix Documents - - - - - - 60 Sources and Bibliography - - - - - 143 Wiltshire’s Nimrod Indexes founded in 1969 by Dr Barbara J Carter J.P., Ph.D., B.Sc., F.S.G. -

American Armies and Battlefields in Europe 533

Chapter xv MISCELLANEOUS HE American Battle Monuments The size or type of the map illustrating Commission was created by Con- any particular operation in no way indi- Tgress in 1923. In carrying out its cates the importance of the operation; task of commeroorating the services of the clearness was the only governing factor. American forces in Europe during the The 1, 200,000 maps at the ends of W or ld W ar the Commission erected a ppro- Chapters II, III, IV and V have been priate memorials abroad, improved the placed there with the idea that while the eight military cemeteries there and in this tourist is reading the text or following the volume records the vital part American tour of a chapter he will keep the map at soldiers and sailors played in bringing the the end unfolded, available for reference. war to an early and successful conclusion. As a general rule, only the locations of Ail dates which appear in this book are headquarters of corps and divisions from inclusive. For instance, when a period which active operations were directed is stated as November 7-9 it includes more than three days are mentioned in ail three days, i. e., November 7, 8 and 9. the text. Those who desire more com- The date giYen for the relief in the plete information on the subject can find front Jine of one division by another is it in the two volumes published officially that when the command of the sector by the Historical Section, Army W ar passed to the division entering the line. -

Earthwork Management at Petersburg National Battlefield

Earthwork Management at Petersburg National Battlefield Dave Shockley Chief, Resource Management Petersburg National Battlefield June, 2000 ******************************************************************************************** TABLE OF CONTENTS ******************************************************************************************** Acknowledgments…….………………………… i Foreword………………………………………... ii Introduction…………………………………….. iii Map of Petersburg National Battlefield…… iv I. Historical Significance A. Earthworks……………………………………….………………………………… 1 B. Archeological Components………………………………………………………... 2 II. Inventory of Existing Earthworks A. Definitions of Earthworks………………………………………………………..… 3 B. Prominent Earthen Structures…..…………………………………………………... 4 C. Engineers Drawings and Current GPS Maps ……………………………………… 6 III. Management Objective……………………….………………………………………….. 23 IV. Conditions/Impacts Affecting Earthworks A. Preservation of Structures and Features………………………………………….… 24 B. Interpretive Values……………………………………………………………….… 33 C. Sustainability……………………………………………………………………..… 34 D. Visitor Accessibility………………………………………………………………... 35 E. Safe Environment…………………………………………………………………... 36 F. Non-historic Resources…………………………………………………………….. 37 G. Additional Issues…………………………………………………………………….38 V. Fundamentals for Earthwork Management at Petersburg National Battlefield A. Tree Removal……………………………………………………………………… 39 B. Erosion Control……………………………………………………………………. 39 C. Seed Selection……………………………………………………………………… 39 D. Hydroseeding…………………………………………………………………….… -

A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations from 1941 to the Present

CRM D0006297.A2/ Final July 2002 Charting the Pathway to OMFTS: A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations From 1941 to the Present Carter A. Malkasian 4825 Mark Center Drive • Alexandria, Virginia 22311-1850 Approved for distribution: July 2002 c.. Expedit'onaryyystems & Support Team Integrated Systems and Operations Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N0014-00-D-0700. For copies of this document call: CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 0 2002 The CNA Corporation Contents Summary . 1 Introduction . 5 Methodology . 6 The U.S. Marine Corps’ new concept for forcible entry . 9 What is the purpose of amphibious warfare? . 15 Amphibious warfare and the strategic level of war . 15 Amphibious warfare and the operational level of war . 17 Historical changes in amphibious warfare . 19 Amphibious warfare in World War II . 19 The strategic environment . 19 Operational doctrine development and refinement . 21 World War II assault and area denial tactics. 26 Amphibious warfare during the Cold War . 28 Changes to the strategic context . 29 New operational approaches to amphibious warfare . 33 Cold war assault and area denial tactics . 35 Amphibious warfare, 1983–2002 . 42 Changes in the strategic, operational, and tactical context of warfare. 42 Post-cold war amphibious tactics . 44 Conclusion . 46 Key factors in the success of OMFTS. 49 Operational pause . 49 The causes of operational pause . 49 i Overcoming enemy resistance and the supply buildup. -

Black's Guide to Devonshire

$PI|c>y » ^ EXETt R : STOI Lundrvl.^ I y. fCamelford x Ho Town 24j Tfe<n i/ lisbeard-- 9 5 =553 v 'Suuiland,ntjuUffl " < t,,, w;, #j A~ 15 g -- - •$3*^:y&« . Pui l,i<fkl-W>«? uoi- "'"/;< errtland I . V. ',,, {BabburomheBay 109 f ^Torquaylll • 4 TorBa,, x L > \ * Vj I N DEX MAP TO ACCOMPANY BLACKS GriDE T'i c Q V\ kk&et, ii £FC Sote . 77f/? numbers after the names refer to the page in GuidcBook where die- description is to be found.. Hack Edinburgh. BEQUEST OF REV. CANON SCADDING. D. D. TORONTO. 1901. BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/blacksguidetodevOOedin *&,* BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE TENTH EDITION miti) fffaps an* Hlustrations ^ . P, EDINBURGH ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1879 CLUE INDEX TO THE CHIEF PLACES IN DEVONSHIRE. For General Index see Page 285. Axniinster, 160. Hfracombe, 152. Babbicombe, 109. Kent Hole, 113. Barnstaple, 209. Kingswear, 119. Berry Pomeroy, 269. Lydford, 226. Bideford, 147. Lynmouth, 155. Bridge-water, 277. Lynton, 156. Brixham, 115. Moreton Hampstead, 250. Buckfastleigh, 263. Xewton Abbot, 270. Bude Haven, 223. Okehampton, 203. Budleigh-Salterton, 170. Paignton, 114. Chudleigh, 268. Plymouth, 121. Cock's Tor, 248. Plympton, 143. Dartmoor, 242. Saltash, 142. Dartmouth, 117. Sidmouth, 99. Dart River, 116. Tamar, River, 273. ' Dawlish, 106. Taunton, 277. Devonport, 133. Tavistock, 230. Eddystone Lighthouse, 138. Tavy, 238. Exe, The, 190. Teignmouth, 107. Exeter, 173. Tiverton, 195. Exmoor Forest, 159. Torquay, 111. Exmouth, 101. Totnes, 260. Harewood House, 233. Ugbrooke, 10P. -

1 the NAVY in the ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Submitted by Michael James

1 THE NAVY IN THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Submitted by Michael James Lea-O’Mahoney, to the University of Exeter, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in September 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned chiefly with the military role of sea power during the English Civil War. Parliament’s seizure of the Royal Navy in 1642 is examined in detail, with a discussion of the factors which led to the King’s loss of the fleet and the consequences thereafter. It is concluded that Charles I was outmanoeuvred politically, whilst Parliament’s choice to command the fleet, the Earl of Warwick, far surpassed him in popularity with the common seamen. The thesis then considers the advantages which control of the Navy provided for Parliament throughout the war, determining that the fleet’s protection of London, its ability to supply besieged outposts and its logistical support to Parliamentarian land forces was instrumental in preventing a Royalist victory. Furthermore, it is concluded that Warwick’s astute leadership went some way towards offsetting Parliament’s sporadic neglect of the Navy. The thesis demonstrates, however, that Parliament failed to establish the unchallenged command of the seas around the British Isles. -

Cornish Worthies, Volume 2 (Of 2) - Sketches of Some Eminemt Cornish Men and Women

Cornish Worthies, Volume 2 (of 2) - Sketches of Some Eminemt Cornish Men and Women By Tregellas, Walter H. English A Doctrine Publishing Corporation Digital Book This book is indexed by ISYS Web Indexing system to allow the reader find any word or number within the document. TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE Italic text is denoted by underscores. Bold text is denoted by =equal signs=. Superscripts (eg y^r) are indicated by ^ and have not been expanded. Dates of form similar to 164-2/3 have been changed to 1642/3. This book was published in two volumes, of which this is the second. Obvious typographical and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources. More detail can be found at the end of the book. CORNISH WORTHIES. With Map, Fcap. 8vo., cloth, 2s. TOURISTS' GUIDE TO CORNWALL AND THE SCILLY ISLES. =Containing full information concerning all the principal Places and Objects of Interest in the County.= By WALTER H. TREGELLAS, Chief Draughtsman, War Office. 'We cannot help expressing our delight with Mr. W. H. Tregellas's masterly "Guide to Cornwall and the Scilly Isles." Mr. Tregellas is an accomplished antiquary and scholar, and writes with love and complete knowledge of his subject. For anyone interested in one of the most interesting English counties we could recommend no better guide to its geology, history, people, old language, industries, antiquities, as well as topography; and the well-selected list of writers on Cornwall will be of the greatest service in enabling the reader to pursue the subject to its limits.'--The Times. -

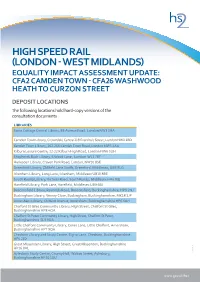

High Speed Rail (London

HIGH SPEED RAIL (London - West MidLands) equaLity Impact assessMent update: cFa2 caMden toWn - cFa26 WashWood heath to curzon street deposit Locations The following locations hold hard-copy versions of the consultation documents LIBRARIES Swiss Cottage Central Library, 88 Avenue Road, London NW3 3HA Camden Town Library, Crowndale Centre 218 Eversholt Street, London NW1 1BD Kentish Town Library, 262-266 Kentish Town Road, London NW5 2AA Kilburn Leisure Centre, 12-22 Kilburn High Road, London NW6 5UH Shepherds Bush Library, 6 Wood Lane , London W12 7BF Harlesden Library, Craven Park Road, London, NW10 8SE Greenford Library, Oldfield Lane South, Greenford, Middlesex, UB6 9LG Ickenham Library, Long Lane, Ickenham, Middlesex UB10 8RE South Ruislip Library, Victoria Road, South Ruislip, Middlesex HA4 0JE Harefield Library, Park Lane, Harefield, Middlesex UB9 6BJ Beaconsfield Library, Reynolds Road, Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, HP9 2NJ Buckingham Library, Verney Close, Buckingham, Buckinghamshire, MK18 1JP Amersham Library, Chiltern Avenue, Amersham, Buckinghamshire HP6 5AH Chalfont St Giles Community Library, High Street, Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire HP8 4QA Chalfont St Peter Community Library, High Street, Chalfont St Peter, Buckinghamshire SL9 9QA Little Chalfont Community Library, Cokes Lane, Little Chalfont, Amersham, Buckinghamshire HP7 9QA Chesham Library and Study Centre, Elgiva Lane, Chesham, Buckinghamshire HP5 2JD Great Missenden Library, High Street, Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire HP16 0AL Aylesbury Study Centre, County -

Notice of Works at Trafford Bridge, Edgcote June 2021 |

Notification Notice of works at Trafford Bridge, Edgcote June 2021 | www.hs2.org.uk High Speed Two (HS2) is the new high speed railway for Britain. We are Duration of works continually reviewing the works on our construction sites in line with Government and Public Health England (PHE) advice on dealing with Works will begin at the COVID-19. The Government’s current strategy makes it clear that end of June and be construction activity can continue as long as it complies with this completed by end of guidance. March 2022 Please be assured that only sites that can operate within the guidelines What to expect are operational. All sites will remain under constant review. We have postponed all face-to-face engagement events and meetings and have To complete this work, put in place a number of channels to communicate with communities, we need to; complete such as letters and phone calls, as well as updates and alerts from each ecology surveys, clear of the local community websites. You can sign up for regular updates in vegetation, undertake your local area at www.hs2innorthants.co.uk planting and transfer marshland turf. What will we be doing? Road closures on Welsh We recently wrote to you with information about the construction of a Road with diversion temporary welfare set up and archaeology works. We now need to let routes you know about the next phase of works which include ecology You may notice some mitigation, vegetation clearance and the translocation of marshland at extra traffic on the Trafford Bridge near Edgcote. -

HS2 Newsletter Chipping Warden to Lower Boddington

Contact our HS2 Helpdesk team on 08081 434 434 HS2 Update Chipping Warden to Lower Boddington | July 2021 High Speed Two (HS2) is the new high speed railway for Britain. In response to COVID -19 we have worked hard to ensure that our working practices are fully aligned with the Site Operating Procedures produced by the Construction Leadership Council. These procedures have been endorsed by Public Health England. We will be keeping our local website www.hs2innorthants.co.uk up to date with information on our works in the local area. Update on our works Our activity in the Chipping Warden area is well underway. The storage areas, office and welfare accommodation at Chipping Warden compound are nearly finished. We have also cleared Join us online… vegetation and started earthworks on the Chipping Warden airfield. Over the summer our activity will increase in the Edgcote, Chipping Virtual one-to-one Warden and Lower Boddington areas and you can expect to see meetings - July 2021 the following works in the local area: We would like to invite • Utility works including trial holes; you to book an • Land surveys to measure land levels; appointment for a virtual • Ground Investigations (GI); one-to-one meeting with • Continued construction of the office accommodation and welfare our engagement team. facilities at Chipping Warden compound; They will be available to • The installation of a concrete batching plant; answer your questions • Further localised clearance of vegetation and fencing along the about the HS2 line of the route; programme and works in • Construction of access and haul roads to move people and your area. -

English Hundred-Names

l LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 1. Bd 30. Nr 1. ,~ ,j .11 . i ~ .l i THE jl; ENGLISH HUNDRED-NAMES BY oL 0 f S. AND ER SON , LUND PHINTED BY HAKAN DHLSSON I 934 The English Hundred-Names xvn It does not fall within the scope of the present study to enter on the details of the theories advanced; there are points that are still controversial, and some aspects of the question may repay further study. It is hoped that the etymological investigation of the hundred-names undertaken in the following pages will, Introduction. when completed, furnish a starting-point for the discussion of some of the problems connected with the origin of the hundred. 1. Scope and Aim. Terminology Discussed. The following chapters will be devoted to the discussion of some The local divisions known as hundreds though now practi aspects of the system as actually in existence, which have some cally obsolete played an important part in judicial administration bearing on the questions discussed in the etymological part, and in the Middle Ages. The hundredal system as a wbole is first to some general remarks on hundred-names and the like as shown in detail in Domesday - with the exception of some embodied in the material now collected. counties and smaller areas -- but is known to have existed about THE HUNDRED. a hundred and fifty years earlier. The hundred is mentioned in the laws of Edmund (940-6),' but no earlier evidence for its The hundred, it is generally admitted, is in theory at least a existence has been found. -

Shrewsbury Battlefield Heritage Assessment (Setting) Edp4686 R002a

Shrewsbury Battlefield Heritage Assessment (Setting) Prepared by: The Environmental Dimension Partnership Ltd On behalf of: Shropshire Council October 2018 Report Reference edp4686_r002a Shrewsbury Battlefield Heritage Assessment (Setting) edp4686_r002a Contents Section 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 Section 2 Methodology............................................................................................................... 3 Section 3 Planning Policy Framework .................................................................................... 11 Section 4 The Registered Battlefield and Relevant Heritage Assets ................................... 15 Section 5 Sensitivity Assessment ........................................................................................... 43 Section 6 Conclusions ............................................................................................................. 49 Section 7 Bibliography ............................................................................................................ 53 Appendices Appendix EDP 1 Brief: Shrewsbury Battlefield Heritage Assessment (Setting) – (Wigley, 2017) Appendix EDP 2 Outline Project Design (edp4686_r001) Appendix EDP 3 English Heritage Battlefield Report: Shrewsbury 1403 Appendix EDP 4 Photographic Register Appendix EDP 5 OASIS Data Collection Form Plans Plan EDP 1 Battlefield Location, Extents and Designated Heritage Assets (edp4686_d001a 05