1 the NAVY in the ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Submitted by Michael James

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEMBROKESHIRE © Lonelyplanetpublications Biggest Megalithicmonumentinwales

© Lonely Planet Publications 162 lonelyplanet.com PEMBROKESHIRE COAST NATIONAL PARK •• Information 163 porpoises and whales are frequently spotted PEMBROKESHIRE COAST in coastal waters. Pembrokeshire The park is also a focus for activities, from NATIONAL PARK hiking and bird-watching to high-adrenaline sports such as surfing, coasteering, sea kayak- The Pembrokeshire Coast National Park (Parc ing and rock climbing. Cenedlaethol Arfordir Sir Benfro), established in 1952, takes in almost the entire coast of INFORMATION Like a little corner of California transplanted to Wales, Pembrokeshire is where the west Pembrokeshire and its offshore islands, as There are three national park visitor centres – meets the sea in a welter of surf and golden sand, a scenic extravaganza of spectacular sea well as the moorland hills of Mynydd Preseli in Tenby, St David’s and Newport – and a cliffs, seal-haunted islands and beautiful beaches. in the north. Its many attractions include a dozen tourist offices scattered across Pembro- scenic coastline of rugged cliffs with fantas- keshire. Pick up a copy of Coast to Coast (on- Among the top-three sunniest places in the UK, this wave-lashed western promontory is tically folded rock formations interspersed line at www.visitpembrokeshirecoast.com), one of the most popular holiday destinations in the country. Traditional bucket-and-spade with some of the best beaches in Wales, and the park’s free annual newspaper, which has seaside resorts like Tenby and Broad Haven alternate with picturesque harbour villages a profusion of wildlife – Pembrokeshire’s lots of information on park attractions, a cal- sea cliffs and islands support huge breeding endar of events and details of park-organised such as Solva and Porthgain, interspersed with long stretches of remote, roadless coastline populations of sea birds, while seals, dolphins, activities, including guided walks, themed frequented only by walkers and wildlife. -

The Professionalisation of the Royal Navy: 1660-1688

The Professionalisation of the Royal Navy: 1660-1688 by Samantha Middleton The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of the University of Portsmouth September 2020 Abstract This thesis analyses the developments made between 1660 and 1688 that contributed towards the Royal Navy becoming a more professionalised organisation. It outlines the impact of individuals and their methods towards achieving professionalisation. The political and financial problems facing the navy before the restoration of the monarchy are also addressed. Biographical case studies of three influential naval reformers; James Stewart, The Duke of York; William Coventry; and Samuel Pepys are used to demonstrate the significant influence that they had on the process of professionalization. This thesis ascertains that although the terminology had not been invented at this stage, the principles of Management Control were implemented by Pepys, Coventry and the Duke of York as a method of organizational professionalisation, identifying examples of performance measurement, rewards systems and the implantation of standard operating procedures. An in-depth analysis of the Duke of York’s instructions for the duties of the Principal Officers demonstrates that the Duke of York introduced enhanced accounting procedures and additional control mechanisms to reduce abuses and increase administrative efficiency. Additionally, a set of professional responsibilities has been created within this thesis for Coventry, whose role as secretary is absent from the instructions. This shows for the first time, that Coventry identified his professional remit as focusing primarily on retrenchment and the reduction of abuses. This contributed towards wider professionalisation. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Six Unpublished Letters of Queen Henrietta Maria

SIX UNPUBLISHED LETTERS OF dUEEN HENRIETTA MARIA R. A. BEDDARD IN the morass of papers left by that diligent servant of the House of Stuart, Sir Edward Nicholas, Secretary of State to Charles I and Charles II, is a small cache of six letters written by, or at the command of, Queen Henrietta Maria.^ Five of them are addressed to Nicholas in his official capacity as Secretary.^ Three of them are informal, being little more than hastily penned notes in the Queen's own hand. These are undated by her, but two of them have been endorsed by Nicholas with the date on which he received them: 5 September and i October 1641. His endorsement locates them in the difficult period of Charles Ts residence in Edinburgh, when his master was seeking to build a party among the Scottish nobles. The third most probably belongs to the same year. All three show that the King was during his absence from England regularly employing his wife in the routine business of despatching, and, on occasion, restraining the time of delivery of his correspondence.^ The other two letters addressed to Secretary Nicholas are of greater historical moment. Not only are they more ample in content, they are also more formal in nature. They belong to a much later period in the Queen's life, when she had taken up residence in her native France following her successful flight from Exeter in July 1644.^ The two communications are cast in the form of royal warrants, drafted by the clerk attending the Queen at the palace of St Germain-en-Laye, outside Paris, where for a time she occupied grace and favour lodgings given to her by her sister-in-law, Anne of Austria, Queen Regent of France and the widow of Louis XIII.^ As such, they are signed by Henrietta Maria at the beginning in the customary fashion, and are dated coram regina 9 and 22 June 1648 respectively, according to the New Style of the Gregorian calendar in use in Catholic France: that is, 30 May and 12 June, according to the Old Style of the Julian computation still in use in Protestant England. -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

Grenville Research

David & Jenny Carter Nimrod Research Docton Court 2 Myrtle Street Appledore Bideford North Devon EX39 1PH www.nimrodresearch.co.uk [email protected] GRENVILLE RESEARCH This report has been produced to accompany the Historical Research and Statement of Significance Reports into Nos. 1 to 5 Bridge Street, Bideford. It should be noted however, that the connection with the GRENVILLE family has at present only been suggested in terms of Nos. 1, 2 and 3 Bridge Street. I am indebted to Andy Powell for locating many of the reference sources referred to below, and in providing valuable historical assistance to progress this research to its conclusions. In the main Statement of Significance Report, the history of the buildings was researched as far as possible in an attempt to assess their Heritage Value, with a view to the owners making a decision on the future of these historic Bideford properties. I hope that this will be of assistance in this respect. David Carter Contents: Executive Summary - - - - - - 2 Who were the GRENVILLE family? - - - - 3 The early GRENVILLEs in Bideford - - - - 12 Buckland Abbey - - - - - - - 17 Biography of Sir Richard GRENVILLE - - - - 18 The Birthplace of Sir Richard GRENVILLE - - - - 22 1585: Sir Richard GRENVILLE builds a new house at Bideford - 26 Where was GRENVILLE’s house on The Quay? - - - 29 The Overmantle - - - - - - 40 How extensive were the Bridge Street Manor Lands? - - 46 Coat of Arms - - - - - - - 51 The MEREDITH connection - - - - - 53 Conclusions - - - - - - - 58 Appendix Documents - - - - - - 60 Sources and Bibliography - - - - - 143 Wiltshire’s Nimrod Indexes founded in 1969 by Dr Barbara J Carter J.P., Ph.D., B.Sc., F.S.G. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

I 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': a NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF

'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 i 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a national study of English justices of the peace (JPs) in the mid- Tudor era. It incorporates comparable data from the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and the Elizabeth I. Much of the analysis is quantitative in nature: chapters compare the appointments of justices of the peace during the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I, and reveal that purges of the commissions of the peace were far more common than is generally believed. Furthermore, purges appear to have been religiously- based, especially during the reign of Elizabeth I. There is a gap in the quantitative data beginning in 1569, only eleven years into Elizabeth I’s reign, which continues until 1584. In an effort to compensate for the loss of quantitative data, this dissertation analyzes a different primary source, William Lambarde’s guidebook for JPs, Eirenarcha. The fourth chapter makes particular use of Eirenarcha, exploring required duties both in and out of session, what technical and personal qualities were expected of JPs, and how well they lived up to them. -

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman, QC. Part I. BERNARD QUARITCH LTD MMXX BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Front cover: from item 106 (Gillray) Rear cover: from item 281 (Peterloo Massacre) Opposite: from item 276 (‘Martial’) List 2020/1 Introduction My father qualified in medicine at Durham University in 1926 and practised in Gateshead on Tyne for the next 43 years – excluding 6 years absence on war service from 1939 to 1945. From his student days he had been an avid book collector. He formed relationships with antiquarian booksellers throughout the north of England. His interests were eclectic but focused on English literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. Several of my father’s books have survived in the present collection. During childhood I paid little attention to his books but in later years I too became a collector. During the war I was evacuated to the Lake District and my school in Keswick incorporated Greta Hall, where Coleridge lived with Robert Southey and his family. So from an early age the Lake Poets were a significant part of my life and a focus of my book collecting. -

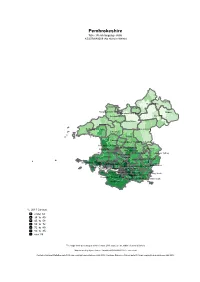

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Cilgerran St. Dogmaels Goodwick Newport Fishguard North West Fishguard North East Clydau Scleddau Crymych Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Solva Maenclochog Letterston Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Portfield Haverfordwest: Castle Narberth Martletwy Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Rural Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Johnston The Havens Llangwm Kilgetty/Begelly Amroth Milford: North Burton St. Ishmael's Neyland: West Milford: WestMilford: East Milford: Hakin Milford: Central Saundersfoot Milford: Hubberston Neyland: East East Williamston Pembroke Dock:Pembroke Market Dock: Central Carew Pembroke Dock: Pennar Penally Pembroke Dock: LlanionPembroke: Monkton Tenby: North Pembroke: St. MaryLamphey North Manorbier Pembroke: St. Mary South Pembroke: St. Michael Tenby: South Hundleton %, 2011 Census under 34 34 to 45 45 to 58 58 to 72 72 to 80 80 to 85 over 85 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) St. Dogmaels Cilgerran Goodwick Newport Fishguard North East Fishguard North West Crymych Clydau Scleddau Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Letterston Solva Maenclochog Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Castle Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Haverfordwest: Portfield The Havens Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Martletwy Narberth Rural Llangwm Johnston Kilgetty/Begelly St. Ishmael's Milford: North Burton Neyland: West East Williamston Amroth Milford: HubberstonMilford: HakinMilford: Neyland:East East Milford: West Saundersfoot Milford: CentralPembroke Dock:Pembroke Central Dock: Llanion Pembroke Dock: Market Penally LampheyPembroke:Carew St. -

Existing Electoral Arrangements

COUNTY OF PEMBROKESHIRE EXISTING COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP Page 1 2012 No. OF ELECTORS PER No. NAME DESCRIPTION ELECTORATE 2012 COUNCILLORS COUNCILLOR 1 Amroth The Community of Amroth 1 974 974 2 Burton The Communities of Burton and Rosemarket 1 1,473 1,473 3 Camrose The Communities of Camrose and Nolton and Roch 1 2,054 2,054 4 Carew The Community of Carew 1 1,210 1,210 5 Cilgerran The Communities of Cilgerran and Manordeifi 1 1,544 1,544 6 Clydau The Communities of Boncath and Clydau 1 1,166 1,166 7 Crymych The Communities of Crymych and Eglwyswrw 1 1,994 1,994 8 Dinas Cross The Communities of Cwm Gwaun, Dinas Cross and Puncheston 1 1,307 1,307 9 East Williamston The Communities of East Williamston and Jeffreyston 1 1,936 1,936 10 Fishguard North East The Fishguard North East ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,473 1,473 11 Fishguard North West The Fishguard North West ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,208 1,208 12 Goodwick The Goodwick ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,526 1,526 13 Haverfordwest: Castle The Castle ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,651 1,651 14 Haverfordwest: Garth The Garth ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,798 1,798 15 Haverfordwest: Portfield The Portfield ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,805 1,805 16 Haverfordwest: Prendergast The Prendergast ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,530 1,530 17 Haverfordwest: Priory The Priory ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,888 1,888 18 Hundleton The Communities of Angle. -

Black's Guide to Devonshire

$PI|c>y » ^ EXETt R : STOI Lundrvl.^ I y. fCamelford x Ho Town 24j Tfe<n i/ lisbeard-- 9 5 =553 v 'Suuiland,ntjuUffl " < t,,, w;, #j A~ 15 g -- - •$3*^:y&« . Pui l,i<fkl-W>«? uoi- "'"/;< errtland I . V. ',,, {BabburomheBay 109 f ^Torquaylll • 4 TorBa,, x L > \ * Vj I N DEX MAP TO ACCOMPANY BLACKS GriDE T'i c Q V\ kk&et, ii £FC Sote . 77f/? numbers after the names refer to the page in GuidcBook where die- description is to be found.. Hack Edinburgh. BEQUEST OF REV. CANON SCADDING. D. D. TORONTO. 1901. BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/blacksguidetodevOOedin *&,* BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE TENTH EDITION miti) fffaps an* Hlustrations ^ . P, EDINBURGH ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1879 CLUE INDEX TO THE CHIEF PLACES IN DEVONSHIRE. For General Index see Page 285. Axniinster, 160. Hfracombe, 152. Babbicombe, 109. Kent Hole, 113. Barnstaple, 209. Kingswear, 119. Berry Pomeroy, 269. Lydford, 226. Bideford, 147. Lynmouth, 155. Bridge-water, 277. Lynton, 156. Brixham, 115. Moreton Hampstead, 250. Buckfastleigh, 263. Xewton Abbot, 270. Bude Haven, 223. Okehampton, 203. Budleigh-Salterton, 170. Paignton, 114. Chudleigh, 268. Plymouth, 121. Cock's Tor, 248. Plympton, 143. Dartmoor, 242. Saltash, 142. Dartmouth, 117. Sidmouth, 99. Dart River, 116. Tamar, River, 273. ' Dawlish, 106. Taunton, 277. Devonport, 133. Tavistock, 230. Eddystone Lighthouse, 138. Tavy, 238. Exe, The, 190. Teignmouth, 107. Exeter, 173. Tiverton, 195. Exmoor Forest, 159. Torquay, 111. Exmouth, 101. Totnes, 260. Harewood House, 233. Ugbrooke, 10P.