Mahendra Naidu A/L R. Manogaran Trading As Sri Sai Traders V Navin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Knowledge on Selection, Sustainable

INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE ON SELECTION, SUSTAINABLE UTILIZATION OF LOCAL FLORA AND FAUNA FOR FOOD BY TRIBES (PTG) OF ODISHA: A POTENTIAL RESOURCE FOR FOOD AND ENVIRONMENTAL SECURITY Prepared by SCSTRTI, Bhubaneswar, Government of Odisha Research Study on “Indigenous knowledge on selection, sustainable utilization of local flora and fauna for food by tribes I (PTG) of Odisha: A potential resource for food and environmental security” ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Research and Training Institute, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar commissioned a study, titled“Indigenous Knowledge on Selection & Sustainable Utilization of Local Flora and Fauna for Food by Tribes (PTGs) of Odisha: A Potential Resource for Food and Environmental Security”,to understand traditional knowledge system on local flora and fauna among the tribal communities of Odisha. This study tries to collect information on the preservation and consumption of different flora and fauna available in their areas during different seasons of the year for different socio-cultural and economic purposes that play important roles in their way of life. During the itinerary of the study, inclusive of other indegenious knowledge system, attempt was also made to understand the calorie intake of different PVTGs of Odisha through anthropometric measurements (height and weight).Including dietary measurement. Resource/Research persons fromCTRAN Consulting, A1-A2, 3rd Floor, Lewis Plaza, Lewis Road, BJB Nagar, Bhubaneswar-14, Odisha extended their technical support for data collection, analysis and report drafting with research inputs and guidance from Internal Research Experts of Directorate of SCSTRTI, Bhubaneswar. CTRAN Consulting and its Resource/Research personsdeserve thanks and complements. Also, thanks are due to all the Internal Experts and Researchers of SCSTRTI, especially Mrs. -

Coffee Break No Uraian Menu 1 2 Macam Kue Asin / Gurih 1

COFFEE BREAK NO URAIAN MENU 1 2 MACAM KUE ASIN / GURIH 1 Arem-arem sayur 2 Bakwan udang 3 Bitterballen 4 Cheese Roll 5 Combro 6 Crekes Telur 7 Gadus / talam udang 8 Gehu pedas 9 Ketan Bumbu 10 Lalampah ikan menado 11 Lemper Ayam Bangka 12 Lemper ayam Spc 13 Lemper bakar Ayam 14 Lemper sapi jateng 15 Lemper sapi rendang / ayam 16 Leupeut ketan kacang 17 Lontong ayam kecil 18 Lontong Oncom 19 Lontong Tahu 20 Lumpia Bengkuang 21 Lumpia goreng ayam 22 Macaroni Panggang 23 Misoa ayam 24 Otak-otak ikan 25 Pangsit goreng ikan 26 Pastel ikan 27 Pastel sayur 28 Pastel sayur telur 29 Risoles rougut ayam 30 Risoles rougut canape 31 Roti Ayam 32 Roti goreng abon sapi 33 Roti goreng sayur 34 Samosa 35 Semar mendem ayam 36 Serabi oncom 37 Sosis solo basah ayam 38 Tahu isi Buhun 2 2 MACAM KUE MANIS 1 Agar-agar moca 2 Ali Agrem 3 Angkleng ketan hitam Cililin 4 Angku jambu angku tomat 5 Angku Ketan Kacang Ijo 6 Apem Jawa 7 Apem Pisang 8 Awug beras kipas 9 Bafel hati 10 Bika Ambon Medan / Suji 11 Bika Iris Cirebon 12 Bika Medan Kecil 13 Bola-Bola Coklat 14 Bolu Gulung blueberry 15 Bolu Ketan Hitam 16 Bolu Kukus Coklat / Gula Merah 17 Bolu Nutri Keju 18 Bolu Pisang Ambon 19 Bolu Susu 20 Bolu Ubi Jepang 21 Bubur Lemu 22 Bubur Lolos 23 Bugis Bogor 24 Bugis ketan Matula 25 Bugis Ubi Ungu 26 Carabika Suji 27 Cenil / gurandil 28 Cente Manis 29 Cikak kacang ijo 30 Clorot 31 Cookies kismis 32 Coy pie pontianak 33 Crumble bluberry 34 Cuhcur gula merah / Suji 35 Cuhcur mini 36 Dadar Gulung 37 Dadar Gulung Santan 38 Gemblong Ketan 39 Getuk 40 Getuk Lindri 41 Gogodoh -

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

Ethnobotanical Study on Local Cuisine of the Sasak Tribe in Lombok Island, Indonesia

J Ethn Foods - (2016) 1e12 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Ethnic Foods journal homepage: http://journalofethnicfoods.net Original article Ethnobotanical study on local cuisine of the Sasak tribe in Lombok Island, Indonesia * Kurniasih Sukenti a, , Luchman Hakim b, Serafinah Indriyani b, Y. Purwanto c, Peter J. Matthews d a Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Mataram University, Mataram, Indonesia b Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia c Laboratory of Ethnobotany, Division of Botany, Biology Research Center-Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Indonesia d Department of Social Research, National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka, Japan article info abstract Article history: Background: An ethnobotanical study on local cuisine of Sasak tribe in Lombok Island was carried out, as Received 4 April 2016 a kind of effort of providing written record of culinary culture in some region of Indonesia. The cuisine Received in revised form studied included meals, snacks, and beverages that have been consumed by Sasak people from gener- 1 August 2016 ation to generation. Accepted 8 August 2016 Objective: The aims of this study are to explore the local knowledge in utilising and managing plants Available online xxx resources in Sasak cuisine, and to analyze the perceptions and concepts related to food and eating of Sasak people. Keywords: ethnobotany Methods: Data were collected through direct observation, participatory-observation, interviews and local cuisine literature review. Lombok Results: In total 151 types of consumption were recorded, consisting of 69 meals, 71 snacks, and 11 Sasak tribe beverages. These were prepared with 111 plants species belonging to 91 genera and 43 families. -

Juadah Kampung Menu

JUADAH KAMPUNG MENU COLD APPERTIZED, SALAD AND CONDIMENTS Assorted Sushi Gado Gado, Rojak Buah, Ulam-ulam Kampong, Selection of Ikan Masin, Tauhu Sumbat, Pulut Kuning dengan Serunding, Pegedil Daging, Acar Buah Acar Rampai, Tempe Goreng Pedas, Telur Masin, Ikan Rabus Goreng, Bendi dengan Sambal Belacan, Terong Bakar dengan Sambal Assorted Western Cold Cut Platter x 2 Assorted Chinese Cold Cut Platter Mixed Salad x 6, Plain Salad x 8, Mango Chutney, Budu, Sambal Belacan, Cencaluk, Spicy Tomato Chutney, Tempoyak, Keropok x 4 Jenis, Papadam x 2 Jenis. Selection of Malay Fruit Pickle (Jeruk), Selection of Western Pickle KERABU Kerabu Mangga Muda, Kerabu Kacang Botol, Kerabu Sotong, Kerabu Nasi, Kerabu Daging, Kerabu Tauge Kerabu Kacang Panjang, Kerabu Jantung Pisang, Kerabu Kaki Ayam, Kerabu Nenas Timun, Kerabu Perut, Kerabu Telur SIDINGS Dates B.B.Q. (DEEPFRIED) STATION Hard Shell Prawn, Tiger Prawn, Fresh Water Prawn, Crab, Mussel, Sotong, Kembong Fish, Pari(Stingray) Fish, Chicken Sathin, Chicken Wing, Chicken Liver, Chicken Kidney, Chicken Drumstick, Chicken Satay, Beef Satay, Beef Tenderloin, Sausages, Whole Lamb, Sweet Corn, Tau Fu Bakar Otak-Otak, Keropak Lekor, Ayam Percik Deep-fried Sweet Potatoes, Yam and Bananas OUT DOOR STALL Sup Gearbox / Sup Campur Nasi Bukhari Lok-Lok Lamb & Chicken with Lebanese Bread or Pita Bread Roti John (Rotate in Daily Menu) Murtabak with Kari Ayam (Rotate in Daily Menu) Roti Canai (Rotate in Daily Menu) Rojak Sotong Kangkung Assorted Dim Sum Air Syrup x 4 Ais Kacang/Cendol Ice Cream with Condiments -

Halia Restaurant Ramadhan Buffet 2018 (17/5,20/5,23/5,26/5,29/5,1/6,4/6,7/6,10/6/2018)

HALIA RESTAURANT RAMADHAN BUFFET 2018 (17/5,20/5,23/5,26/5,29/5,1/6,4/6,7/6,10/6/2018) MENU1 Live Stall 1- Appitizer Thai Som Tum Salad, Kerabu Mangga, Sotong Kangkung (Live) Ulam Ulaman Tradisonal (Pegaga, Daun Selom, Ulam Raja, Jantung Pisang, Kacang Botol, Tempe Goreng) Sambal Belacan, Sambal Mangga, Sambal Tempoyak, Cincaluk, Budu, Sambal Gesek Ikan Masin Bulu Ayam, Ikan Masin Sepat dan Ikan Kurau, Ikan Perkasam, Telor Masin Keropok Ikan, Keropok Udang, Keropok Sayur dan Papadhom Live Stall 2 - Mamak Delights Rojak Pasembor with Peanut Sauce & Crackers Live Stall 3 - Soup Aneka Sup Berempah (Bakso Daging, Ayam, Daging, Perut, Tulang Kambing, Tulang Rawan, Ekor, Gear Box) ( Mee Kuning, Bee Hoon, Kuey Teow) Condiments – (Taugeh, Daun Bawang, Daun Sup, Bawang Goreng, Cili Kicap) Roti Benggali Curry Mee with Condiments Bubur - Bubur Lambuk Berherba dan Sambal Main Dishes Ayam Masak Lemak Rebung Stired Fried Beef with Black Pepper Sauce Perut Masak Lemak Cili Padi Ikan Pari Asam Nyonya Prawn with Salted Eggs Sotong Sambal Tumis Petai Stired Fried Pok Choy with Shrimp Paste Nasi Putih Live Stall 4 - Japanese Section Assorted Sushi and Sashimi, Assorted Tempura, Udon / Soba & Sukiyaki Live Stall 5 – Pasta Corner Assorted Pizza (Margarita, Pepperoni, Futi De Mare ) Spaghetti, Penne & Futtuchini with Bolognese, Cabonnara and Tomato Concasse Sauce Live Stall 6 - Sizzler Hot Plate (Assorted Vegetables, Squid, Fish Slice, Clam, Prawn, Mussel, Bamboo Clam) (Sauces: Sweet & Sour, Black Oyster Sauce, Black Pepper & Tom Yam) Live Stall 7 - Steamboat -

A Dictionary of Kristang (Malacca Creole Portuguese) with an English-Kristang Finderlist

A dictionary of Kristang (Malacca Creole Portuguese) with an English-Kristang finderlist PacificLinguistics REFERENCE COpy Not to be removed Baxter, A.N. and De Silva, P. A dictionary of Kristang (Malacca Creole Portuguese) English. PL-564, xxii + 151 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 2005. DOI:10.15144/PL-564.cover ©2005 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Pacific Linguistics 564 Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, East Timor, southeast and south Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Publications are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise, who are usually not members of the editorial board. FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: John Bowden, Malcolm Ross and Darrell Tryon (Managing Editors), I Wayan Arka, Bethwyn Evans, David Nash, Andrew Pawley, Paul Sidwell, Jane Simpson EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Karen Adams, Arizona State University Lillian Huang, National Taiwan Normal Peter Austin, School of Oriental and African University Studies -

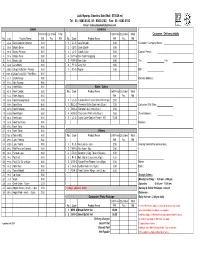

Copy of Order Form Oct 2013 New Price Copy

Lulu Nyonya Goodies Sdn Bhd ( 573034-w) Tel : 03 - 9283 8182, 03 - 9282 6182 Fax : 03 - 9283 3182 Email : [email protected] Sweet Savories Unit Price Qty Order Total Unit Price Qty Order Total Customer / Delivery details No. Code Product Name RM Pcs RM No. Code Product Name RM Pcs RM 1 BS-G Batik Sago wt Coconut 0.80 1 CL-G Cara Berlauk 0.80 Customer / Company Name : 2 BB-G Bingka Beras 0.80 2 CB-G Cucur Badak 0.80 3 BP-G Bingka Pandan 0.80 3 LC-G *Lobak Cake 0.80 Contact Person : 4 BT-G Bingka Telur 0.80 4 CPP-G Mini Pulut Panggang 0.80 5 BU-G Bingka Ubi 0.80 5 POP-G Yam Cake 0.80 Tel : Fax : 6 CM-G Cara Manis 0.80 6 PP-G Curry Puff 1.50 7 CNB-G Crispy Nutty Ball - Peanut 0.80 7 YC-G Popiah 1.50 H/P : 8 CNB1-G Crispy Nutty Ball - Red Bean 0.80 9 CS-G Crystal Sago 0.80 Delivery Address : 10 KLK-G Kole Kacang 0.80 11 KB-G Kueh Bakar 0.80 Bake / Cakes 12 KC-G Kueh Cendol 0.80 No. Code Product Name Unit Price Qty Order Total 13 KJ-G Kueh Jagung 0.80 RM Pcs RM 14 KM-G Kueh Kacang Merah 0.80 1 CC-G *Carrot Cheese Cake Slice(min.30 pc ) 2.50 15 KKR-G Kueh Keria 0.80 2 BCC-G *Premium Butter Cake (min.30 pc ) 1.50 Collection / Del. -

Delight Your House Guests This Hari Raya with Deliciously Cooked 'Ketupat' and 'Kueh' Baked with Tefal's Induction

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Delight your house guests this Hari Raya with deliciously cooked ‘ketupat’ and ‘kueh’ baked with Tefal’s Induction Spherical Pot Rice Cooker This new innovative, multi-tasking cooker not only deliciously cooks your ‘ketupat’, but also perfectly bakes your ‘kueh’! Singapore, 5 June 2017 – Anyone who receives a constant stream of guests during the festive Hari Raya season will appreciate the innovation behind Tefal’s new Induction Spherical Pot Rice Cooker (Model no: RK8045). Multi-tasking (you can choose from ‘Stew’, ‘Slow Cook’ and even ‘Bake’), time-saving and promising irresistibly fluffy rice every time, this is the kitchen innovation you want in your kitchen to delight your stream of guests this Hari Raya! The secret behind delicious, fluffy rice and ‘lontong’? Its innovative spherical and induction pot technology (exclusive to Tefal) With the Induction Spherical Pot Rice Cooker, the days of fretting over under-cooked or over-cooked rice is now over. The combination of Tefal’s exclusive induction technology and spherical pot delivers evenly-balanced heat distribution within the pot, allowing for homogenous cooking and delicious fluffy rice every time. Page 1 of 4 Inspired by the traditional methods of cooking rice over the fire, Tefal’s innovative spherical pot are orbed at a 62 degree angle at the brim and bottom to encourage even heat circulation by swirling rice grains circularly rather than vertically. Its 2D spherical heating technology emits heat from the sides and bottom of the pot. This, coupled with its induction pot feature where an electric current from external vessel creates a magnetic field, generating a surrounding efficient heating convection, creates the optimal heat for homogenous and deliciously cooked rice. -

Identifikasi Bakteri Penyebab Kerusakan Pada Nasi Uduk Berbahan Baku Beras Organik Dan Non Organik Varietas Ir-64 Identification

IDENTIFIKASI BAKTERI PENYEBAB KERUSAKAN PADA NASI UDUK BERBAHAN BAKU BERAS ORGANIK DAN NON ORGANIK VARIETAS IR-64 IDENTIFICATION OF SPOILAGE BACTERIA IN “UDUK” RICE BASED ON IR-64 VARIETY OF ORGANIC AND NON ORGANIC SKRIPSI Diajukan untuk memenuhi sebagian dari syarat-syarat guna memperoleh gelar Sarjana Teknologi Pangan Oleh : NAOMI CHRISMA PERMATASARI 12.70.0118 PROGRAM STUDI TEKNOLOGI PANGAN FAKULTAS TEKNOLOGI PERTANIAN UNIVERSITAS KATOLIK SOEGIJAPRANATA SEMARANG 2016 PERNYATAAN KEASLIAN SKRIPSI Saya yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini : Nama : Naomi Chrisma Permatasari NIM : 12.70.0118 Fakultas : Teknologi Pertanian Program Studi : Teknologi Pangan Menyatakan bahwa skripsi “Identifikasi Bakteri Penyebab Kerusakan Pada Nasi Uduk Berbahan Baku Beras Organik dan Non Organik Varietas IR-64” merupakan karya saya dan tidak terdapat karya yang pernah diajukan untuk memperoleh gelar kesarjanaan di suatu perguruan tinggi. Sepanjang pengetahuan saya juga tidak terdapat karya atau pendapat yang pernah ditulis atau diterbitkan oleh orang lain, kecuali secara tertulis diacu dalam naskah ini dan disebutkan dalam daftar pustaka. Apabila saya tidak jujur, maka gelar dan ijazah yang saya peroleh dinyatakan batal dan akan saya kembalikan kepada Universitas Katolik Soegijapranata, Semarang. Demikian pernyataan ini saya buat dan dapat dipergunakan sebagaimana mestinya. Semarang, 13 Mei 2016 Naomi Chrisma Permatasari ii IDENTIFIKASI BAKTERI PENYEBAB KERUSAKAN PADA NASI UDUK BERBAHAN BAKU BERAS ORGANIK DAN NON ORGANIK VARIETAS IR-64 IDENTIFICATION OF SPOILAGE BACTERIA IN “UDUK” RICE BASED ON IR-64 VARIETY OF ORGANIC AND NON ORGANIC Oleh : NAOMI CHRISMA PERMATASARI NIM : 12.70.0118 Program Studi : Teknologi Pangan Skripsi ini telah disetujui dan dipertahankan di hadapan sidang penguji pada tanggal : 13 Mei 2016 Semarang, 13 Mei 2016 Fakultas Teknologi Pertanian Universitas Katolik Soegijapranata Pembimbing I, Dekan, Dr. -

I Satuan Gramatikal Dan Dasar Penamaan Kue Jajanan Pasar Di Kios Snack Berkah Bu Harjono Pasar Lempuyangan Kota Yogyakarta

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI SATUAN GRAMATIKAL DAN DASAR PENAMAAN KUE JAJANAN PASAR DI KIOS SNACK BERKAH BU HARJONO PASAR LEMPUYANGAN KOTA YOGYAKARTA Skripsi Diajukan untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Sastra Indonesia Program Studi Sastra Indonesia Oleh Anindita Ayu Gita Coelestia NIM: 174114039 PROGRAM STUDI SASTRA INDONESIA FAKULTAS SASTRA UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2021 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ABSTRAK Coelestia, Anindita Ayu Gita. 2021. “Satuan Gramatikal dan Dasar Penamaan Kue Jajanan Pasar di Kios Snack Berkah Bu Harjono Pasar Lempuyangan Kota Yogyakarta”. Skripsi Strata Satu (S1). Program Studi Sastra Indonesia, Fakultas Sastra, Universitas Sanata Dharma. Skripsi ini mengkaji satuan gramatikal dan dasar penamaan kue jajanan pasar di Kios Snack Berkah Bu Harjono Pasar Lempuyangan Kota Yogyakarta. Rumusan masalah yang dibahas dalam penelitian ini, yakni (i) satuan gramatikal nama kue jajanan pasar dan (ii) dasar penamaan nama kue jajanan pasar. Tujuan penelitian ini adalah mendeskripsikan satuan gramatikal dan dasar penamaan nama kue jajanan pasar di Kios Snack Berkah Bu Harjono Pasar Lempuyangan Kota Yogyakarta. Objek penelitian ini berupa nama kue jajanan pasar di Kios Snack Berkah Bu Harjono Pasar Lempuyangan Kota Yogyakarta. Metode pengumpulan data dilakukan dengan menggunakan metode simak (pengamatan atau observasi), yaitu metode yang digunakan dengan cara peneliti melakukan penyimakan penggunaan bahasa (Mahsun, 2005: 242). Selanjutnya digunakan teknik catat dan teknik simak bebas libat cakap. Teknik simak bebas libat cakap adalah peneliti berperan sebagai pengamat penggunaan bahasa oleh informannya (Mahsun, 2005: 92). Serta digunakan pula teknik wawancara. Selanjutnya data yang sudah diklasifikasi dianalisis menggunakan metode agih dengan teknik sisip, bagi unsur langsung (BUL), dan teknik baca markah. -

SPICY CHICKEN with RICE CAKES and CABBAGE Dak Gali This Is a Spicy Comfort-Food Classic from the City of Chuncheon in the Northeast Region of South Korea

SPICY CHICKEN WITH RICE CAKES AND CABBAGE Dak Gali This is a spicy comfort-food classic from the city of Chuncheon in the northeast region of South Korea. Many college students from Seoul will get on a train and head to the northeast side of the peninsula to watch the sun rise over the East Sea, then head downtown, where a street full of dak galbi restaurants all claim to offer an “authentic” version of this dish. Various add-ins include cooked sweet potato noodles, potatoes, and rice cakes. Rice cakes (ddeok) come in cylindrical shapes but vary in thickness. The thicker ones are often sliced and cooked in soups such as New Year’s Day Soup (page 87). Thinner cylinders are commonly found in street foods, such as Braised Rice Cakes (page 69), which are simmered in gochujang sauce; the chewy texture and ability to absorb all the favors make this a much-beloved dish in Korea. We wanted to keep the chicken the star, but feel free to up the amount of rice cakes to 2 cups if you fnd them as addictive as we do. The surprise ingredient is a few pinches of hot Madras curry powder added to the spicy marinade. It adds rich depth to the dish and renders it extremely addictive. MAKES 4 TO 6 SERVINGS 3 tablespoons gochujang About 2 pounds boneless, skinless chicken thighs (preferably organic), cut into bite-size pieces 2 to 3 tablespoons gochugaru 1 cup (8 ounces) Korean rice cake (cylinder shape) 2 tablespoons low-sodium soy sauce 1 tablespoon vegetable oil 2 tablespoons granulated sugar 1 ⁄2 head green or white cabbage, cut into large cubes 2 tablespoons