2011 Iic Student & Emerging Conservator Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michelle Lynn Brown 44 Maryland Ave, Saranac Lake, NY 12983 (518) 524-0468 [email protected]

Michelle Lynn Brown 44 Maryland Ave, Saranac Lake, NY 12983 (518) 524-0468 [email protected] EDUCATION University of Vermont, Vermont Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit Ongoing PhD, Natural Resources Dissertation: “Effects of Forest Biomass Energy Production on Northern Forest Sustainability and Biodiversity” University of Vermont, Vermont Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit 2012 MS, Natural Resources Thesis: “Predicting Impacts of Future Human Population Growth and Development on Occupancy Rates and Landscape Carrying Capacity of Forest-Dependent Birds” Penn State University, Graduate GIS Certificate 2005 Binghamton University, State University of New York 2001 BS, Environmental Studies Concentration in Ecosystems, Magna Cum Laude TEACHING EXPERIENCE Instructor, Population Dynamics and Modeling, University of Vermont 2014 • Co-taught 30 graduate students and federal employees using a live online format Graduate Teaching Program Ongoing • Completed more than 50 hours of mentored teaching, observations, and workshops PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Conservation Scientist The Nature Conservancy, Adirondack Chapter 2007- Keene Valley, NY • Led regional team to integrate climate resilience into transportation infrastructure design (five states and three provinces) • Secured more than $1,200,000 to incorporate conservation objectives into New York State transportation planning and implementation; managed projects • Led ecological assessment and science strategy for 161,000-acre land protection project Conservation Planner The -

PAINTINGS CONSERVATOR Collections and Information Access Center

Job CIA.4.14 PAINTINGS CONSERVATOR Collections and Information Access Center REPORTS TO: Senior Conservator SUPERVISES: None The Oakland Museum of California values are fundamental to our institutional culture and guide our work together. Excellence: We are committed to excellence and working at the highest standards of integrity and professionalism. Community: We believe everyone should feel welcome and part of our community, both within the Museum and with our visitors and neighbors. Innovation: We embrace innovation and calculated risk-taking to achieve our mission. Commitment: Our work at the Museum demonstrates a sense of purpose and a shared accountability for the institution’s success. POSITION SUMMARY The Paintings Conservator is responsible for the welfare of the paintings within the collection by monitoring the environment, pest activity, and advocating for proper handling, packing, shipping, storage, and exhibit. Incumbent performs skilled conservation work on collections within their specialization including research, examination, documentation, treatment, and preventative maintenance. ESSENTIAL DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES The following reflects OMCA’s definition of essential functions for this position, but does not restrict the tasks that may be assigned. OMCA may assign or reassign duties and responsibilities to this position at any time due to reasonable accommodation or other reasons. INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSIBILITIES • Support the Museum’s mission, values, vision, and core commitment to the visitor experience, community -

Core Conservation Courses (Finh-Ga.2101-2109)

Conservation Course Descriptions—Full List Conservation Center, Institute of Fine Arts Page 1 of 38, 2/05/2020 CORE CONSERVATION COURSES (FINH-GA.2101-2109) MATERIAL SCIENCE OF ART & ARCHAEOLOGY I FINH-GA.2101.001 [#reg. code] (Lecture, 3 points) Instructor Hours to be arranged Location TBD The course extends over two terms and is related to Technology and Structure of Works of Art I and II. Emphasis during this term is on problems related to the study and conservation of organic materials found in art and archaeology from ancient to contemporary periods. The preparation, manufacture, and identification of the materials used in the construction and conservation of works of art are studied, as are mechanisms of degradation and the physicochemical aspects of conservation treatments. Enrollment is limited to conservation students and other qualified students with the permission of the faculty of the Conservation Center. This course is required for first-year conservation students. MATERIAL SCIENCE OF ART & ARCHAEOLOGY II FINH-GA.2102.001 [#reg. code] (Lecture, 3 points) Instructor Hours to be arranged Location TBD The course extends over two terms and is related to Technology and Structure of Works of Art I and II. Emphasis during this term is on the chemistry and physics of inorganic materials found in art and archaeological objects from ancient to contemporary periods. The preparation, manufacture, and identification of the materials used in the construction and conservation of works of art are studied, as are mechanisms of degradation and the physicochemical aspects of conservation treatments. Each student is required to complete a laboratory assignment with a related report and an oral presentation. -

Protecting Cultural Heritage

Protecting Cultural Heritage Reflections on the Position of conservation science. Important players in this field, Science in Multidisciplinary which readily address interactivity and networking, are the recently started Episcon project in the European Approaches Community’s Marie Curie program3 and the five- 4 by Jan Wouters year-old EU-Artech project. The goal of Episcon is to develop the first generation of actively formed ver the past 40 years, scientific research activ- conservation scientists at the Ph.D.-level in Europe. ities in support of the conservation and resto- EU-Artech provides access, research, and technology Oration of objects and monuments belonging for the conservation of European cultural heritage, to the world’s cultural heritage, have grown in number including networking among 13 European infrastruc- and quality. Many institutes specifically dedicated to tures operating in the field of artwork conservation. the study and conservation of cultural heritage have The present absence of a recognized, knowledge- emerged. Small dedicated laboratories have been based identity for conservation science or conserva- installed in museums, libraries, and archives, and, tion scientists may lead to philosophical and even more recently, university laboratories are showing linguistic misunderstandings within multidisciplinary increased interest in this field. consortiums created to execute conservation projects. This paper discusses sources of misunderstandings, However, no definition has been formulated to iden- a suggestion for more transparent language when tify the specific tasks, responsibilities, and skills of a dealing with the scientific term analysis, elements to conservation scientist or of conservation science. This help define conservation science, and the benefits is contradictory to the availability of a clear Definition for conservation scientists of becoming connected to of the Profession of a Conservator-Restorer, published worldwide professional networks. -

January 28, 2021 Introductions Faculty

Art Conservation Open House January 28, 2021 Introductions Faculty Debra Hess Norris Dr. Jocelyn Alcántara-García Brian Baade Maddie Hagerman Dr. Joyce Hill Stoner Nina Owczarek Photograph Conservator Conservation Scientist Paintings Conservator Objects Conservator Paintings Conservator Objects Conservator Chair and Professor of Photograph Associate Professor Assistant Professor Instructor Edward F. and Elizabeth Goodman Rosenberg Assistant Professor Conservation Professor of Material Culture Unidel Henry Francis du Pont Chair Students Director, Preservation Studies Doctoral Program Annabelle Camp Kelsey Marino Katie Rovito Miriam-Helene Rudd Art conservation major, Class of 2019 Art conservation major, Class of 2020 WUDPAC Class of 2022 Senior art conservation major, WUDPAC Class of 2022 Preprogram conservator Paintings major Class of 2021 Textile major, organic objects minor President of the Art Conservation Club What is art conservation? • Art conservation is the field dedicated to preserving cultural property • Preventive and interventive • Conservation is an interdisciplinary field that relies heavily on chemistry, art history, history, anthropology, ethics, and art Laura Sankary cleans a porcelain plate during an internship at UD Art Conservation at the University of Delaware • Three programs • Undergraduate degree (BA or BS) • Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation or WUDPAC (MS) at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library near Wilmington, DE • Doctorate in Preservation Studies (PhD) Miriam-Helene Rudd cleans a -

CONSERVATORS/RESTORERS Updated: 8/2015

CONSERVATORS/RESTORERS Updated: 8/2015 **THE HOOD MUSEUM OF ART DOES NOT RECOMMEND SPECIFIC CONSERVATORS. THIS LISTING IS MADE FOR PURPOSES OF INFORMATION ONLY.** Online directory of members of AIC (American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic works): www.conservation-us.org/membership/find-a-conservator GENERAL – Also see individual media below Straus Center for conservation and Technical Studies Harvard University Art Museums 32 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Paper, Objects, Textiles P: 617/495.2392 F: 617/495.0322 Website: www.harvardartmuseums.org Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum 25 Evans Way Boston, MA 02115 P: 617/566.1401 Paper, Objects, Textiles F: 617/278.5167 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gardnermuseum.org Vermont Museum and Gallery Alliance C/O Fairbanks Museum Referrals. Good source for general 1302 Main Street information on storage, packing, and St. Johnsbury, VT 05819 care of artwork. P: 802/751.8381 Williamstown Art Conservation Center, Inc. 227 South Street Williamstown, MA 02167 Paintings, paper, objects, furniture, P: 413/458.5741 sculpture, frames, analytical F: 413/458.2314 Email: [email protected] Website: www.williamstownart.org Worcester Art Museum 55 Salisbury Street Worcester, MA 01609 Paper, Paintings P: 508/799.4406 Email: [email protected] Website: www.worcesterart.org CONSERVATORS/RESTORERS Updated: 8/2015 General Continued Art Conservation Resource Center 262 Beacon Street, #4 Paintings, paper, photographs, textiles, Boston, MA 02116 objects and sculpture P: -

2009 Final Program

AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR CONSERVATION OF HISTORIC AND ARTISTIC WORKS 37TH ANNUAL MEETING MAY 19-22, 2009 HYATT REGENCY CENTURY PLAZA LOS ANGELES, CA conservation 2.0 new directions FINAL PROGRAM BOARD OF DIRECTORS WELCOME FROM THE PRESIDENT Martin Burke President Meg Loew Craft Vice President Lisa Bruno Secretary Welcome to Los Angeles and AIC’s 37th Annual Brian Howard Treasurer Catharine Hawks Director, Committees & Task Forces Meeting! Since AIC’s first Annual Meeting in 1972, Paul Messier Director, Communications the meeting has grown to include workshops, Karen Pavelka Director, Professional Education Ralph Wiegandt Director, Specialty Groups tours, posters, lectures, and discussions. Many members and non-members attend each year to ANNUAL MEETING COMMITTEES take advantage of this exceptional opportunity to Meg Loew Craft Program Committee Jennifer Wade exchange ideas and information, learn about new Rebecca Rushfield products and services from our industry suppliers, and explore our Margaret A. Little Paul Himmelstein host city. Make sure to take advantage of the many opportunities Gordon Lewis that come from having so many of your peers in one place, at one Valinda Carroll Poster Session Committee Rachel Penniman time. Angela M. Elliot Jerry Podany Local Arrangements Committee This year’s meeting theme, Conservation 2.0—New Directions, Holly Moore emphasizes ways in which emerging technologies are affecting Jo Hill Ellen Pearlstein the field of conservation. The general session and specialty group Janice Schopfer Laura Stalker program committees have put together a variety of presentations Anna Zagorski that explore this theme. Papers will outline and showcase recent SPECIALTY GROUP OFFICERS advances in all specialties and address scientific analysis, treatment Architecture methods, material improvements, and documentation. -

The Meaning of Materials in Modern and Contemporary

2012 AICCM Paintings Group + 20th Century in Paint Symposium The Meaning of Materials in Modern and Contemporary Art 2012 AICCM Paintings Group + 20th Century in Paint Symposium The Meaning of Materials in Modern and Contemporary Art Cinema B, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane 10-11 December 2012 1 2 3 Contents Supporters Supporters / 5 Jointly organised by ‘The Twentieth Century in Paint’ Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Project headed by The Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation at the University Welcome Message / 6 of Melbourne, the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Centre for Contemporary Art Conservation and the Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Materials General Information / 9 (AICCM) Paintings Special Interest Group. Program / 10 The organizing committee would like to acknowledge the support of the Ian Potter Foundation. Tru Vue, the manufacturer of high-performance glazing for framing and Symposium Abstracts / 15 display applications is also pleased to support this symposium. For more information on Tru Vue glazing products, contact Jared Davis, Megawood Larson Juhl at JDavis@ Author Profiles / 32 megawoodlarsonjuhl.com.au or visit www:tru-vue.com/museums. Acknowledgments / 42 Location Map / 44 4 5 This is particularly interesting in painting media through revolutionary art contemporary museum practice. The practices in the 20th century in Australia Welcome processes by which artists transfer and parts of Southeast Asia. The project knowledge to institutions and collectors for concludes -

Conservation of Cultural and Scientific Objects

CHAPTER NINE 335 CONSERVATION OF CULTURAL AND SCIENTIFIC OBJECTS In creating the National Park Service in 1916, Congress directed it "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life" in the parks.1 The Service therefore had to address immediately the preservation of objects placed under its care. This chapter traces how it responded to this charge during its first 66 years. Those years encompassed two developmental phases of conservation practice, one largely empirical and the other increasingly scientific. Because these tended to parallel in constraints and opportunities what other agencies found possible in object preservation, a preliminary review of the conservation field may clarify Service accomplishments. Material objects have inescapably finite existence. All of them deteriorate by the action of pervasive external and internal agents of destruction. Those we wish to keep intact for future generations therefore require special care. They must receive timely and. proper protective, preventive, and often restorative attention. Such chosen objects tend to become museum specimens to ensure them enhanced protection. Curators, who have traditionally studied and cared for museum collections, have provided the front line for their defense. In 1916 they had three principal sources of information and assistance on ways to preserve objects. From observation, instruction manuals, and formularies, they could borrow the practices that artists and craftsmen had developed through generations of trial and error. They might adopt industrial solutions, which often rested on applied research that sought only a reasonable durability. And they could turn to private restorers who specialized in remedying common ills of damaged antiques or works of art. -

Therembrandtdatabase Newsletter #4, May 2016 Research Resource on Rembrandt Paintings

TheRembrandtDatabase Newsletter #4, May 2016 research resource on Rembrandt paintings Gemäldegalerie Berlin research project • Rijksmuseum X-ray films online • A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings • Zeph Benders and the History Painting from the Lakenhal • Sample documentation RCE • The Rembrandt Database presents: project associate Marijke Heslenfeld Now online: 11,083 files, 205 Rijksmuseum X-ray films paintings, 25 collections online And more content is in preparation; please A selection of X-radiographs from keep an eye out for updates on our website! the Rijksmuseum has been added to the database, among which X-ray film, 18-06-1956, Rembrandt, Bust of a woman smiling, X-rays of paintings from The possibly Saskia van Uylenburgh, dated 1633, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister Dresden Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Research project Gemäldegalerie Berlin (almost) completed Dresden. th On April 18 another five Rembrandt paintings from the Gemäldegalerie were The Rijksmuseum keeps a large presented in The Rembrandt Database. By the end of June our colleagues in Berlin – collection of X-rays of not only Claudia Laurenze-Landsberg and Katja Kleinert – will complete the art-historical and paintings from their own technical research of the Rembrandt paintings. The collaboration with the collection, but also of paintings Gemäldegalerie has been unique regarding the intense research they have performed from other institutions. A and all the results they have gathered. By combining technical and art-historical substantial part of these X-rays research within an interdisciplinary team the project has achieved innovative and most were produced during the interesting results. landmark Rembrandt exhibition, which was held at the The extensive art-historical information and the visual and textual data that has Rijksmuseum and the Museum emerged from technical analyses of all 26 Rembrandt paintings in the collection of the Boijmans van Beuningen in 1956. -

Newsletter # 90 March2004 V2

No.90 March 2004 National Newsletter Australian Institute of the Conservation of Cultural Material (Inc.) ISSN 0727-0364 President’s Report Eric Archer contents I hope that you have had a refreshing and restful break, as I did in Tasmania. Welcome to the new and re-elected National Council members - I am looking forward to working President’s Report 1 with you in the year ahead. There has been one change to National Council since the From the Editorial Committee 2 October meeting - Kay Söderlund has not been able to continue her work with the Education portfolio due to time constraints and business commitments - she will, however, In the Next Issue 2 remain on National Council with Membership Services responsibilities. Many thanks to Feature Article: To infinity… 3 Kay for the work she has done, particularly during the closure of the University of Canberra Letter to The Editor 6 course and the AICCM National Training Summit held in Canberra in March last year. Lab Profile 7 One year on from a hectic 2003 term - which included AICCM’s response to the closure Obituary 9 of the University of Canberra course; the National Training Summit in Canberra; AICCM’s The Centre For Cultural 10 response to the war in Iraq and subsequent looting and damage to cultural property; the Materials Conservation devastating bushfires in the ACT and Victoria; and supporting and developing SIG People & Places 11 activities – National Council will focus on a strategic agenda based on sustainability; Reviews 21 funding; accreditation; planning the October 2004 Meeting, and continued strengthening of SIG activities. -

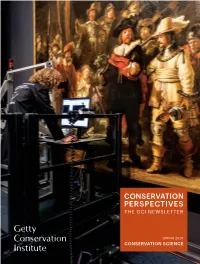

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES the Gci Newsletter

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES THE GCI NEWSLETTER SPRING 2020 CONSERVATION SCIENCE A Note from As this issue of Conservation Perspectives was being prepared, the world confronted the spread of coronavirus COVID-19, threatening the health and well-being of people across the globe. In mid-March, offices at the Getty the Director closed, as did businesses and institutions throughout California a few days later. Getty Conservation Institute staff began working from home, continuing—to the degree possible—to connect and engage with our conservation colleagues, without whose efforts we could not accomplish our own work. As we endeavor to carry on, all of us at the GCI hope that you, your family, and your friends, are healthy and well. What is abundantly clear as humanity navigates its way through this extraordinary and universal challenge is our critical reliance on science to guide us. Science seeks to provide the evidence upon which we can, collectively, make decisions on how best to protect ourselves. Science is essential. This, of course, is true in efforts to conserve and protect cultural heritage. For us at the GCI, the integration of art and science is embedded in our institutional DNA. From our earliest days, scientific research in the service of conservation has been a substantial component of our work, which has included improving under- standing of how heritage was created and how it has altered over time, as well as developing effective conservation strategies to preserve it for the future. For over three decades, GCI scientists have sought to harness advances in science and technology Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI Anna Flavin, Photo: to further our ability to preserve cultural heritage.