Core Conservation Courses (Finh-Ga.2101-2109)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michelle Lynn Brown 44 Maryland Ave, Saranac Lake, NY 12983 (518) 524-0468 [email protected]

Michelle Lynn Brown 44 Maryland Ave, Saranac Lake, NY 12983 (518) 524-0468 [email protected] EDUCATION University of Vermont, Vermont Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit Ongoing PhD, Natural Resources Dissertation: “Effects of Forest Biomass Energy Production on Northern Forest Sustainability and Biodiversity” University of Vermont, Vermont Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit 2012 MS, Natural Resources Thesis: “Predicting Impacts of Future Human Population Growth and Development on Occupancy Rates and Landscape Carrying Capacity of Forest-Dependent Birds” Penn State University, Graduate GIS Certificate 2005 Binghamton University, State University of New York 2001 BS, Environmental Studies Concentration in Ecosystems, Magna Cum Laude TEACHING EXPERIENCE Instructor, Population Dynamics and Modeling, University of Vermont 2014 • Co-taught 30 graduate students and federal employees using a live online format Graduate Teaching Program Ongoing • Completed more than 50 hours of mentored teaching, observations, and workshops PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Conservation Scientist The Nature Conservancy, Adirondack Chapter 2007- Keene Valley, NY • Led regional team to integrate climate resilience into transportation infrastructure design (five states and three provinces) • Secured more than $1,200,000 to incorporate conservation objectives into New York State transportation planning and implementation; managed projects • Led ecological assessment and science strategy for 161,000-acre land protection project Conservation Planner The -

Protecting Cultural Heritage

Protecting Cultural Heritage Reflections on the Position of conservation science. Important players in this field, Science in Multidisciplinary which readily address interactivity and networking, are the recently started Episcon project in the European Approaches Community’s Marie Curie program3 and the five- 4 by Jan Wouters year-old EU-Artech project. The goal of Episcon is to develop the first generation of actively formed ver the past 40 years, scientific research activ- conservation scientists at the Ph.D.-level in Europe. ities in support of the conservation and resto- EU-Artech provides access, research, and technology Oration of objects and monuments belonging for the conservation of European cultural heritage, to the world’s cultural heritage, have grown in number including networking among 13 European infrastruc- and quality. Many institutes specifically dedicated to tures operating in the field of artwork conservation. the study and conservation of cultural heritage have The present absence of a recognized, knowledge- emerged. Small dedicated laboratories have been based identity for conservation science or conserva- installed in museums, libraries, and archives, and, tion scientists may lead to philosophical and even more recently, university laboratories are showing linguistic misunderstandings within multidisciplinary increased interest in this field. consortiums created to execute conservation projects. This paper discusses sources of misunderstandings, However, no definition has been formulated to iden- a suggestion for more transparent language when tify the specific tasks, responsibilities, and skills of a dealing with the scientific term analysis, elements to conservation scientist or of conservation science. This help define conservation science, and the benefits is contradictory to the availability of a clear Definition for conservation scientists of becoming connected to of the Profession of a Conservator-Restorer, published worldwide professional networks. -

Conservation of Cultural and Scientific Objects

CHAPTER NINE 335 CONSERVATION OF CULTURAL AND SCIENTIFIC OBJECTS In creating the National Park Service in 1916, Congress directed it "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life" in the parks.1 The Service therefore had to address immediately the preservation of objects placed under its care. This chapter traces how it responded to this charge during its first 66 years. Those years encompassed two developmental phases of conservation practice, one largely empirical and the other increasingly scientific. Because these tended to parallel in constraints and opportunities what other agencies found possible in object preservation, a preliminary review of the conservation field may clarify Service accomplishments. Material objects have inescapably finite existence. All of them deteriorate by the action of pervasive external and internal agents of destruction. Those we wish to keep intact for future generations therefore require special care. They must receive timely and. proper protective, preventive, and often restorative attention. Such chosen objects tend to become museum specimens to ensure them enhanced protection. Curators, who have traditionally studied and cared for museum collections, have provided the front line for their defense. In 1916 they had three principal sources of information and assistance on ways to preserve objects. From observation, instruction manuals, and formularies, they could borrow the practices that artists and craftsmen had developed through generations of trial and error. They might adopt industrial solutions, which often rested on applied research that sought only a reasonable durability. And they could turn to private restorers who specialized in remedying common ills of damaged antiques or works of art. -

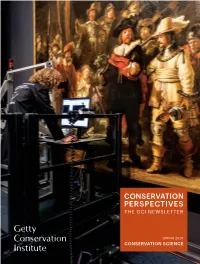

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES the Gci Newsletter

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES THE GCI NEWSLETTER SPRING 2020 CONSERVATION SCIENCE A Note from As this issue of Conservation Perspectives was being prepared, the world confronted the spread of coronavirus COVID-19, threatening the health and well-being of people across the globe. In mid-March, offices at the Getty the Director closed, as did businesses and institutions throughout California a few days later. Getty Conservation Institute staff began working from home, continuing—to the degree possible—to connect and engage with our conservation colleagues, without whose efforts we could not accomplish our own work. As we endeavor to carry on, all of us at the GCI hope that you, your family, and your friends, are healthy and well. What is abundantly clear as humanity navigates its way through this extraordinary and universal challenge is our critical reliance on science to guide us. Science seeks to provide the evidence upon which we can, collectively, make decisions on how best to protect ourselves. Science is essential. This, of course, is true in efforts to conserve and protect cultural heritage. For us at the GCI, the integration of art and science is embedded in our institutional DNA. From our earliest days, scientific research in the service of conservation has been a substantial component of our work, which has included improving under- standing of how heritage was created and how it has altered over time, as well as developing effective conservation strategies to preserve it for the future. For over three decades, GCI scientists have sought to harness advances in science and technology Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI Anna Flavin, Photo: to further our ability to preserve cultural heritage. -

CATS Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CATS Centre for Art Technological Studies and Conservation The centre is a strategic research partnership between three Copenhagen based research institutions Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK) The National Museum of Denmark (NMD) The School of Conservation at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation (KADK) The cornerstone of CATS is technical art history, which is an interdisciplinary field of research between conservators, natural scientists and scholars from art historical and cultural studies. Technical art history investigates the making and meaning of art works, painting techniques and artists’ materials. A main objective of the research centre is to develop new and more exact methods to diagnose, treat and preserve our art historical heritage. The exploration of artistic practices is aimed at shedding light on the complex and fascinating cartography of ageing processes within works of art – to contribute to and advance the field of technical art history. The establishment of the Centre for Art Technological Studies and Conservation was made possible by a donation by the Villum Foundation and the Velux Foundation, and is a collaborate research venture between Statens Museum for Kunst, the National Museum of Denmark and the School of Conservation at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation. Contact CATS Website: www.cats-cons.dk E-mail: [email protected] 2 CATS Annual Report, January - December 2018 Contents INTRODUCTION -

BROMEC 36 Bulletin of Research on Metal Conservation

BROMEC 36 Bulletin of Research on Metal Conservation Editorial July 2016 BROMEC 36 contains seven abstracts on research covering archaeological, historic and modern metals conservation. They comprise a call for collaboration by a consortium in southern France that is endeavouring to remove copper staining from outdoor stone using non-toxic materials. Also, two projects from Brazil present their material diagnosis approaches to informing conservation strategies. The first focuses on contemporary metals used in the structures and finishes of architecture and sculpture, while the second is for an item of industrial heritage; a steamroller which features in the title image for this issue of BROMEC. Further ways of diagnosing materials and their degradation mechanisms are outlined in a Swiss abstract concerned with cans containing foodstuffs. This work will also be presented at ICOM-CC’s upcoming Metal 2016 conference in New Delhi: 26-30 September 2016. Updates on ongoing projects in France and Spain are given too. In France, a new shared laboratory has been established to progress the subcritical stabilisation method for archaeological iron and also for optimising protection by organic coatings of metallic artefacts exposed to air. In Spain, works on in situ Anglophone editor & translator: electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for evaluating protection by coatings and James Crawford [email protected] patinas have been extended to acquire larger data sets from heritage and over Francophone coeditor: multiple time intervals. Lastly, insights into comparing the efficacy of spraying and Michel Bouchard brushing Paraloid B-72 for protecting wrought iron are given in laboratory research mbouchard caraa.fr Francophone translators: from the United Kingdom. -

Center for Biodiversity and Conservation

Center for Biodiversity and Conservation Progress Update Spring 2021 Dear CBC Friends & Colleagues, Understanding life on Earth and how to sustain it for the future is the fundamental challenge of our time. For almost 30 years, the Center for Biodiversity and Conservation has been advancing research, strengthening human capacity, and creating connections to help the Museum meet this challenge. This past year has brought an unprecedented crisis, yet I am extremely proud of what our small team at the Center has achieved. The Year in Numbers 40 Publications 35 Peer-reviewed 29 Open access 6 With local partners 10 With students, interns, mentees 8 Awards, honors, or appointments 17 Presentations at professional meetings 27 Invited talks 28 Contributions to AMNH programs 12 Popular articles, media appearances or coverage 15 Funding proposals 8 With DEIJ dimensions/objectives 9 With external partners 23 Average number of interns, mentees, and trainees per semester 8 New software tools, modules and other resources produced (all open access) CBC Director of Biodiversity Informatics Research Dr. Mary Blair Notable and collaborators have been selected for new funding under NASA’s Ecological Forecasting Program to deepen and expand our awards and current NASA-funded collaboration with the Colombia Biodiversity appointments Observation Network. Dr. Blair and other scientists leading the CBC’s Machine Learning for Conservation projects are looking forward to collaborating with the Museum’s Department of Education on their new National Science Foundation (NSF) award focused on preparing high school students for careers in machine learning through mentored scientific research. The $1.48 million grant will span three years, and will expand opportunities for science-interested students to apply machine learning approaches to research in biology, including conservation biology. -

1 Curriculum Vitae Prof. Dr. Ron Spronk Professor of Art History

Curriculum Vitae Prof. Dr. Ron Spronk Professor of Art History Department of Art History and Art Conservation Ontario Hall, Room 322 67 University Avenue Kingston, Ontario Canada K7L 3N6 Hieronymus Bosch Special Chair Radboud University Nijmegen Netherlands T: 613 533-6000, extension 78288 F: 613 533-6891 E: [email protected] Degrees: Ph.D., Groningen University, Netherlands, Department of History of Art and Architecture, 2005. Doctoral Candidacy, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA, Art History Department, 1994. Master’s degree equivalent (Dutch Doctoraal Diploma), Groningen University, Netherlands, Department of History of Art and Architecture, 1993. Current affiliations: Since 2007: Professor of Art History (tenured), Department of Art History and Art Conservation, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Department Head from 2007 to 2010. Since 2010: Hieronymus Bosch Special Chair, Radboud University Nijmegen, Netherlands (Bijzonder Hoogleraar, 0.2 FTE). Employment history: 2006-2007: Research Curator, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museum, Cambridge MA, USA. 2005-2007: Lecturer on History of Art and Architecture, Department of History of Art and Architecture, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. 1999-2006: Associate Curator for Research, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museum, Cambridge MA, USA. 2004: Lecturer, Department of History of Art and Architecture, Groningen University, Netherlands. 1997-1999: Research Associate for Technical Studies, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museum, Cambridge MA, USA. 1996-1997: Andrew W. Mellon Research Fellow, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museum, Cambridge MA, USA. 1995-1996: Special Conservation Intern, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museum, Cambridge MA, USA. -

Is a Filmmaker, Visual Artist, Programmer, and Writer, As Well As

is a filmmaker, visual artist, programmer, and writer, as well as a media conservation and digitization specialist at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC. Her multimedia works and films have been shown nationally, including at Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, TX, List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, MA, Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, Atlanta, GA, and the Studio Museum, the Maysles Cinema, and Microscope Gallery, all in New York City. Archer was previously a studio artist in the Whitney Independent Study program, a NYFA Multidisciplinary Fellow, a 2005 Creative Capital grantee in film and video, and she has been awarded numerous residencies. A contributor to Film Comment Magazine as well as other film periodicals and three blogs (Continuum Film Blog, Black Leader, Ina’s Horror Blog), she received a BA in Film/Video from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and an MA in Cinema Studies from New York University. is associate professor of comparative literature and visual studies at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, where she is also dean of Humanities and Arts. Since 2013 she has been a research associate in the VIAD Research Centre in the faculty of Art, Design, and Architecture at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Her areas of research span literature and philosophy, contemporary art, and photography, with a linguistic and cultural focus on French and Francophone worlds and a geographic focus on contemporary Africa. She was lead curator of C.A.O.S. (Contemporary Africa on Screen) at the South London Gallery in 2010–2011, and has been awarded fellowships from the Mellon Foundation, the Marion and Jasper Whiting Foundation, the Andy Warhol Foundation, and the Clark Art Institute, among others. -

Graduate Programs in Art History

The CAA Directory 2017 Art History Arts Administration Curatorial & Museum GRADUATE Studies Library Science PROGRAMS Financial Aid Special Programs in art history Facilities & More 978 1 939461 44 5 INTRODUCTION iv About CAA iv Why Graduate School in the Arts v What This Directory Contains v Program Entry Contents v Admissions v Curriculum CONTENTS vi Students vi Faculty vi Resources and Special Programs vi Financial Information vii Kinds of Degrees vii A Note on Methodology GRADUATE PROGRAMS 1 Art History with Visual Studies and Architectural History 140 Arts Administration 157 Curatorial and Museum Studies 184 Library Science INDEXES 190 Alphabetical Index of Schools 191 Geographic Index of Schools ABOUT WHAT THIS DIRECTORY CONTAINS TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) score, bachelor’s degree, college transcripts, letters of recommendation, a personal Graduate Programs in Art History is a comprehensive directory of statement, foreign language proficiency, writing sample or under- programs offered primarily in the English language that grant graduate research paper, and related work experience. a graduate degree in the study of art. (For graduate programs in the practice of art, please see the companion volume, Graduate Programs in the Visual Arts.) Programs offering an advanced degree The CollegeCollege Art Association CURRICULUM WHY GRADUGRADUATEATE in art history and related disciplines are included here. This section lists information about general or specialized courses represents the professional SSCHOOLCHOOL of study, number of courses or credit hours required for gradua- interests of artists, art historians, Listings are divided into four general subject groups: tion, and other degree requirements. IN THE ARTS • Art History COURSES: Institutions usually include the number of courses museum curators, educators, (including the history of architecture and visual studies) that the department offers to graduate students each term and • Arts Administration students, and others in the United the number whose enrollment is limited to graduate students. -

2011 Iic Student & Emerging Conservator Conference

2011 IIC STUDENT & EMERGING CONSERVATOR CONFERENCE CONSERVATION FUTURES AND RESPONSIBILITIES TRANSCRIPTS – 2 of 3 Session 2, Saturday 17th September “Planning a professional career how did the professionals get to where they are? How do they see conservation work and responsibilities changing over the coming years?” Moderator Adam M Klupś Adam M Klupś [Unrecorded preamble: My name is Adam M Klupś and I have recently graduated from UCL with a degree in History of Art with Material Studies. I am about to start my MA in Principles of Conservation here at the Institute. My plan is to become an archaeological conservator and I am using the word ‘plan’ on purpose. I am sure that many of you consider your professional ambitions as a plan, possibly still subject to change. It happens very often and entirely naturally that we get to the same point via different routes or end up being miles apart even though the starting point is the same. In today’s session I would like to think about the issue of planning in relation to a professional career in the field of conservation as it is today, in the 21st century. This will lead us to the question on the current state of the conservation discipline and new responsibilities that appear before us, we who are soon to become conservation professionals.] Introducing our speakers for this session: from the left is Bronwyn Ormsby, a Senior Conservation Scientist at Tate, who introduced me to the world of conservation science. Bronwyn also teaches at UCL and at the Courtauld Institute. Next to Bronwyn we have Duygu Camurcuoglu, originally from Turkey, now based in London. -

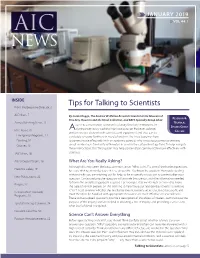

Tips for Talking to Scientists from the Executive Director, 3

JANUARY 2019 » VOL 44:1 INSIDE Tips for Talking to Scientists From the Executive Director, 3 AIC News, 7 By Corina Rogge, The Andrew W. Mellon Research Scientist at the Museum of RESEARCH & Fine Arts, Houston and the Menil Collection, and RATS Specialty Group Chair Annual Meeting News, 12 TECHNICAL ccess to conservation scientists is a luxury for many institutions, let STUDIES GROUP Aalone conservators working in private practice. However, colleges FAIC News, 13 COLUMN and universities abound with scientists and equipment and thus can be Emergency Programs, 13 a valuable resource for those in need of analysis. The issue becomes how Funding, 14 to communicate effectively with an academic scientist who is not accustomed to thinking Courses, 15 about or who lacks familiarity with materials used in the cultural heritage field. To help navigate these interactions, this “field guide” may help conservators communicate more effectively with JAIC News, 16 scientists. Allied Organizations, 18 What Are You Really Asking? Although this may seem like basic common sense, “What is this?” is one of the hardest questions Health & Safety, 19 for a scientist to answer because it is so unspecific. You know the problem that you’re dealing with and why you are reaching out for help, so be as specific as you can to contextualize your New Publications, 22 question. Contextualizing the question will provide the scientist with the information needed to frame the analytical approach required. For example, statements such as “I need to know People, 22 the type of varnish present on this painting to help figure out appropriate solvents to remove it” or “I need to know whether this taxidermy mount contains an arsenic-based pesticide and Conservation Graduate must therefore be handled with appropriate measures” are most effective on several levels.