This Presentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michelle Lynn Brown 44 Maryland Ave, Saranac Lake, NY 12983 (518) 524-0468 [email protected]

Michelle Lynn Brown 44 Maryland Ave, Saranac Lake, NY 12983 (518) 524-0468 [email protected] EDUCATION University of Vermont, Vermont Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit Ongoing PhD, Natural Resources Dissertation: “Effects of Forest Biomass Energy Production on Northern Forest Sustainability and Biodiversity” University of Vermont, Vermont Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit 2012 MS, Natural Resources Thesis: “Predicting Impacts of Future Human Population Growth and Development on Occupancy Rates and Landscape Carrying Capacity of Forest-Dependent Birds” Penn State University, Graduate GIS Certificate 2005 Binghamton University, State University of New York 2001 BS, Environmental Studies Concentration in Ecosystems, Magna Cum Laude TEACHING EXPERIENCE Instructor, Population Dynamics and Modeling, University of Vermont 2014 • Co-taught 30 graduate students and federal employees using a live online format Graduate Teaching Program Ongoing • Completed more than 50 hours of mentored teaching, observations, and workshops PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Conservation Scientist The Nature Conservancy, Adirondack Chapter 2007- Keene Valley, NY • Led regional team to integrate climate resilience into transportation infrastructure design (five states and three provinces) • Secured more than $1,200,000 to incorporate conservation objectives into New York State transportation planning and implementation; managed projects • Led ecological assessment and science strategy for 161,000-acre land protection project Conservation Planner The -

Core Conservation Courses (Finh-Ga.2101-2109)

Conservation Course Descriptions—Full List Conservation Center, Institute of Fine Arts Page 1 of 38, 2/05/2020 CORE CONSERVATION COURSES (FINH-GA.2101-2109) MATERIAL SCIENCE OF ART & ARCHAEOLOGY I FINH-GA.2101.001 [#reg. code] (Lecture, 3 points) Instructor Hours to be arranged Location TBD The course extends over two terms and is related to Technology and Structure of Works of Art I and II. Emphasis during this term is on problems related to the study and conservation of organic materials found in art and archaeology from ancient to contemporary periods. The preparation, manufacture, and identification of the materials used in the construction and conservation of works of art are studied, as are mechanisms of degradation and the physicochemical aspects of conservation treatments. Enrollment is limited to conservation students and other qualified students with the permission of the faculty of the Conservation Center. This course is required for first-year conservation students. MATERIAL SCIENCE OF ART & ARCHAEOLOGY II FINH-GA.2102.001 [#reg. code] (Lecture, 3 points) Instructor Hours to be arranged Location TBD The course extends over two terms and is related to Technology and Structure of Works of Art I and II. Emphasis during this term is on the chemistry and physics of inorganic materials found in art and archaeological objects from ancient to contemporary periods. The preparation, manufacture, and identification of the materials used in the construction and conservation of works of art are studied, as are mechanisms of degradation and the physicochemical aspects of conservation treatments. Each student is required to complete a laboratory assignment with a related report and an oral presentation. -

Protecting Cultural Heritage

Protecting Cultural Heritage Reflections on the Position of conservation science. Important players in this field, Science in Multidisciplinary which readily address interactivity and networking, are the recently started Episcon project in the European Approaches Community’s Marie Curie program3 and the five- 4 by Jan Wouters year-old EU-Artech project. The goal of Episcon is to develop the first generation of actively formed ver the past 40 years, scientific research activ- conservation scientists at the Ph.D.-level in Europe. ities in support of the conservation and resto- EU-Artech provides access, research, and technology Oration of objects and monuments belonging for the conservation of European cultural heritage, to the world’s cultural heritage, have grown in number including networking among 13 European infrastruc- and quality. Many institutes specifically dedicated to tures operating in the field of artwork conservation. the study and conservation of cultural heritage have The present absence of a recognized, knowledge- emerged. Small dedicated laboratories have been based identity for conservation science or conserva- installed in museums, libraries, and archives, and, tion scientists may lead to philosophical and even more recently, university laboratories are showing linguistic misunderstandings within multidisciplinary increased interest in this field. consortiums created to execute conservation projects. This paper discusses sources of misunderstandings, However, no definition has been formulated to iden- a suggestion for more transparent language when tify the specific tasks, responsibilities, and skills of a dealing with the scientific term analysis, elements to conservation scientist or of conservation science. This help define conservation science, and the benefits is contradictory to the availability of a clear Definition for conservation scientists of becoming connected to of the Profession of a Conservator-Restorer, published worldwide professional networks. -

January 28, 2021 Introductions Faculty

Art Conservation Open House January 28, 2021 Introductions Faculty Debra Hess Norris Dr. Jocelyn Alcántara-García Brian Baade Maddie Hagerman Dr. Joyce Hill Stoner Nina Owczarek Photograph Conservator Conservation Scientist Paintings Conservator Objects Conservator Paintings Conservator Objects Conservator Chair and Professor of Photograph Associate Professor Assistant Professor Instructor Edward F. and Elizabeth Goodman Rosenberg Assistant Professor Conservation Professor of Material Culture Unidel Henry Francis du Pont Chair Students Director, Preservation Studies Doctoral Program Annabelle Camp Kelsey Marino Katie Rovito Miriam-Helene Rudd Art conservation major, Class of 2019 Art conservation major, Class of 2020 WUDPAC Class of 2022 Senior art conservation major, WUDPAC Class of 2022 Preprogram conservator Paintings major Class of 2021 Textile major, organic objects minor President of the Art Conservation Club What is art conservation? • Art conservation is the field dedicated to preserving cultural property • Preventive and interventive • Conservation is an interdisciplinary field that relies heavily on chemistry, art history, history, anthropology, ethics, and art Laura Sankary cleans a porcelain plate during an internship at UD Art Conservation at the University of Delaware • Three programs • Undergraduate degree (BA or BS) • Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation or WUDPAC (MS) at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library near Wilmington, DE • Doctorate in Preservation Studies (PhD) Miriam-Helene Rudd cleans a -

CONSERVATORS/RESTORERS Updated: 8/2015

CONSERVATORS/RESTORERS Updated: 8/2015 **THE HOOD MUSEUM OF ART DOES NOT RECOMMEND SPECIFIC CONSERVATORS. THIS LISTING IS MADE FOR PURPOSES OF INFORMATION ONLY.** Online directory of members of AIC (American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic works): www.conservation-us.org/membership/find-a-conservator GENERAL – Also see individual media below Straus Center for conservation and Technical Studies Harvard University Art Museums 32 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Paper, Objects, Textiles P: 617/495.2392 F: 617/495.0322 Website: www.harvardartmuseums.org Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum 25 Evans Way Boston, MA 02115 P: 617/566.1401 Paper, Objects, Textiles F: 617/278.5167 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gardnermuseum.org Vermont Museum and Gallery Alliance C/O Fairbanks Museum Referrals. Good source for general 1302 Main Street information on storage, packing, and St. Johnsbury, VT 05819 care of artwork. P: 802/751.8381 Williamstown Art Conservation Center, Inc. 227 South Street Williamstown, MA 02167 Paintings, paper, objects, furniture, P: 413/458.5741 sculpture, frames, analytical F: 413/458.2314 Email: [email protected] Website: www.williamstownart.org Worcester Art Museum 55 Salisbury Street Worcester, MA 01609 Paper, Paintings P: 508/799.4406 Email: [email protected] Website: www.worcesterart.org CONSERVATORS/RESTORERS Updated: 8/2015 General Continued Art Conservation Resource Center 262 Beacon Street, #4 Paintings, paper, photographs, textiles, Boston, MA 02116 objects and sculpture P: -

Digital Reconstruction of an Archaeological Site Based on the Integration of 3D Data and Historical Sources

International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-5/W1, 2013 3D-ARCH 2013 - 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures, 25 – 26 February 2013, Trento, Italy DIGITAL RECONSTRUCTION OF AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE BASED ON THE INTEGRATION OF 3D DATA AND HISTORICAL SOURCES G. Guidi a, *, M. Russo b, D. Angheleddu a a Dept. of Mechanics, Politecnico di Milano, Italy (gabriele.guidi, davide.angheleddu)@polimi.it b Dept. of Design, Politecnico di Milano, Italy [email protected] Commission V, WG V/4 KEY WORDS: 3D survey, archaeological sites, reality based modeling, digital reconstruction, integration of methods, Cham Architecture ABSTRACT: The methodology proposed in this paper in based on an integrated approach for creating a 3D digital reconstruction of an archaeological site, using extensively the 3D documentation of the site in its current state, followed by an iterative interaction between archaeologists and digital modelers, leading to a progressive refinement of the reconstructive hypotheses. The starting point of the method is the reality-based model, which, together with ancient drawings and documents, is used for generating the first reconstructive step. Such rough approximation of a possible architectural structure can be annotated through archaeological considerations that has to be confronted with geometrical constraints, producing a reduction of the reconstructive hypotheses to a limited set, each one to be archaeologically evaluated. This refinement loop on the reconstructive choices is iterated until the result become convincing by both points of view, integrating in the best way all the available sources. The proposed method has been verified on the ruins of five temples in the My Son site, a wide archaeological area located in central Vietnam. -

Conservation of Cultural and Scientific Objects

CHAPTER NINE 335 CONSERVATION OF CULTURAL AND SCIENTIFIC OBJECTS In creating the National Park Service in 1916, Congress directed it "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life" in the parks.1 The Service therefore had to address immediately the preservation of objects placed under its care. This chapter traces how it responded to this charge during its first 66 years. Those years encompassed two developmental phases of conservation practice, one largely empirical and the other increasingly scientific. Because these tended to parallel in constraints and opportunities what other agencies found possible in object preservation, a preliminary review of the conservation field may clarify Service accomplishments. Material objects have inescapably finite existence. All of them deteriorate by the action of pervasive external and internal agents of destruction. Those we wish to keep intact for future generations therefore require special care. They must receive timely and. proper protective, preventive, and often restorative attention. Such chosen objects tend to become museum specimens to ensure them enhanced protection. Curators, who have traditionally studied and cared for museum collections, have provided the front line for their defense. In 1916 they had three principal sources of information and assistance on ways to preserve objects. From observation, instruction manuals, and formularies, they could borrow the practices that artists and craftsmen had developed through generations of trial and error. They might adopt industrial solutions, which often rested on applied research that sought only a reasonable durability. And they could turn to private restorers who specialized in remedying common ills of damaged antiques or works of art. -

Mitigating the Curation Crisis of the 21St Century

A California Case Study on Procedures to Reassemble and Reevaluate Archaeological Artifact Processing: Mitigating the Curation Crisis of the 21st Century By Allysha A. Leonard Senior Thesis Advisor: Tsim Schneider Submitted to the Department of Anthropology University of California Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, CA 95060 3/20/19 In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor’s in Anthropology Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ 2 I. Abstract ........................................................................................................................................ 3 II. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6 Background in Under Processing: Lack of Analysis .................................................................. 8 Background in Over Processing: Artifact Hoarding and Lack of Ethical Deaccessioning ........ 9 Defining Waste and Defects in the Artifact Process ................................................................. 16 Defining Lean Systems and Kaizen Waste Improvement Strategies ........................................ 17 III. Methods and Case Studies ...................................................................................................... 21 A “A Reality Check” — Field Lab and CRM Experience: Sesnon House, Cabrillo College, Soquel, CA ............................................................................................................................... -

The Licit and the Illicit in Archaeological and Heritage Discourses

CHALLENGING THE DICHOTOMY EDIT ED BY LES FIELD CRISTÓBAL GNeccO JOE WATKINS CHALLENGING THE DICHOTOMY • The Licit and the Illicit in Archaeological and Heritage Discourses TUCSON The University of Arizona Press www.uapress.arizona.edu © 2016 by The Arizona Board of Regents Open-access edition published 2020 ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3130-1 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-4169-0 (open-access e-book) The text of this book is licensed under the Creative Commons Atrribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivsatives 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Cover designed by Leigh McDonald Publication of this book is made possible in part by the Wenner-Gren Foundation. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Field, Les W., editor. | Gnecco, Cristóbal, editor. | Watkins, Joe, 1951– editor. Title: Challenging the dichotomy : the licit and the illicit in archaeological and heritage discourses / edited by Les Field, Cristóbal Gnecco, and Joe Watkins. Description: Tucson : The University of Arizona Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016007488 | ISBN 9780816531301 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Archaeology. | Archaeology and state. | Cultural property—Protection. Classification: LCC CC65 .C47 2016 | DDC 930.1—dc23 LC record available at https:// lccn.loc.gov/2016007488 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. -

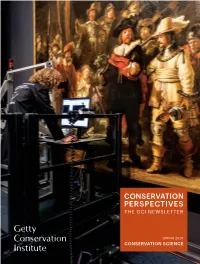

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES the Gci Newsletter

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES THE GCI NEWSLETTER SPRING 2020 CONSERVATION SCIENCE A Note from As this issue of Conservation Perspectives was being prepared, the world confronted the spread of coronavirus COVID-19, threatening the health and well-being of people across the globe. In mid-March, offices at the Getty the Director closed, as did businesses and institutions throughout California a few days later. Getty Conservation Institute staff began working from home, continuing—to the degree possible—to connect and engage with our conservation colleagues, without whose efforts we could not accomplish our own work. As we endeavor to carry on, all of us at the GCI hope that you, your family, and your friends, are healthy and well. What is abundantly clear as humanity navigates its way through this extraordinary and universal challenge is our critical reliance on science to guide us. Science seeks to provide the evidence upon which we can, collectively, make decisions on how best to protect ourselves. Science is essential. This, of course, is true in efforts to conserve and protect cultural heritage. For us at the GCI, the integration of art and science is embedded in our institutional DNA. From our earliest days, scientific research in the service of conservation has been a substantial component of our work, which has included improving under- standing of how heritage was created and how it has altered over time, as well as developing effective conservation strategies to preserve it for the future. For over three decades, GCI scientists have sought to harness advances in science and technology Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI Anna Flavin, Photo: to further our ability to preserve cultural heritage. -

AAA2021 Session Themes V2

SESSION THEMES After Archaeology in Practice: Student Research in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Management An extraordinary and excitingly diverse range of research topics are pursued by students in archaeology and cultural heritage management and with the advent of covid-19, students have engaged with history, science and culture in ways we haven’t even begun to fully explore. Disseminating your research results to an audience of archaeologists at Australia’s annual conference was a huge hit at the 2019 AAA Conference on the Gold Coast and by request we propose to run a student-led and focussed session for the 2021 AAA conference. This session focusses on student research and provides an opportunity to speak alongside a group of your peers in a safe moderated space. We support and encourage student researchers at all levels to present a paper on their research in any area of archaeology and cultural heritage management from national and international contexts. Presenting in this forum allows you to develop important skills at communicating your research results. Presentations will be a maximum of 10-15minutes with 5 minutes for questions. Archaeological Science Collaborations: The ARCAS Network Session Archaeological science has become an integral part of Australian archaeology, with advancements in technologies allowing new types of data and/or higher resolution data to be produced. These data underpin detailed and nuanced interpretations of past human behaviour and contribute to understanding how people lived on Country. Archaeological science, with its foundations in western science, can play an important role in reconciliation and truth telling, especially when combined with the traditional knowledges of First Nation people. -

BROMEC 36 Bulletin of Research on Metal Conservation

BROMEC 36 Bulletin of Research on Metal Conservation Editorial July 2016 BROMEC 36 contains seven abstracts on research covering archaeological, historic and modern metals conservation. They comprise a call for collaboration by a consortium in southern France that is endeavouring to remove copper staining from outdoor stone using non-toxic materials. Also, two projects from Brazil present their material diagnosis approaches to informing conservation strategies. The first focuses on contemporary metals used in the structures and finishes of architecture and sculpture, while the second is for an item of industrial heritage; a steamroller which features in the title image for this issue of BROMEC. Further ways of diagnosing materials and their degradation mechanisms are outlined in a Swiss abstract concerned with cans containing foodstuffs. This work will also be presented at ICOM-CC’s upcoming Metal 2016 conference in New Delhi: 26-30 September 2016. Updates on ongoing projects in France and Spain are given too. In France, a new shared laboratory has been established to progress the subcritical stabilisation method for archaeological iron and also for optimising protection by organic coatings of metallic artefacts exposed to air. In Spain, works on in situ Anglophone editor & translator: electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for evaluating protection by coatings and James Crawford [email protected] patinas have been extended to acquire larger data sets from heritage and over Francophone coeditor: multiple time intervals. Lastly, insights into comparing the efficacy of spraying and Michel Bouchard brushing Paraloid B-72 for protecting wrought iron are given in laboratory research mbouchard caraa.fr Francophone translators: from the United Kingdom.