Curation Standards and Procedures, As Amended

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 28, 2021 Introductions Faculty

Art Conservation Open House January 28, 2021 Introductions Faculty Debra Hess Norris Dr. Jocelyn Alcántara-García Brian Baade Maddie Hagerman Dr. Joyce Hill Stoner Nina Owczarek Photograph Conservator Conservation Scientist Paintings Conservator Objects Conservator Paintings Conservator Objects Conservator Chair and Professor of Photograph Associate Professor Assistant Professor Instructor Edward F. and Elizabeth Goodman Rosenberg Assistant Professor Conservation Professor of Material Culture Unidel Henry Francis du Pont Chair Students Director, Preservation Studies Doctoral Program Annabelle Camp Kelsey Marino Katie Rovito Miriam-Helene Rudd Art conservation major, Class of 2019 Art conservation major, Class of 2020 WUDPAC Class of 2022 Senior art conservation major, WUDPAC Class of 2022 Preprogram conservator Paintings major Class of 2021 Textile major, organic objects minor President of the Art Conservation Club What is art conservation? • Art conservation is the field dedicated to preserving cultural property • Preventive and interventive • Conservation is an interdisciplinary field that relies heavily on chemistry, art history, history, anthropology, ethics, and art Laura Sankary cleans a porcelain plate during an internship at UD Art Conservation at the University of Delaware • Three programs • Undergraduate degree (BA or BS) • Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation or WUDPAC (MS) at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library near Wilmington, DE • Doctorate in Preservation Studies (PhD) Miriam-Helene Rudd cleans a -

CONSERVATORS/RESTORERS Updated: 8/2015

CONSERVATORS/RESTORERS Updated: 8/2015 **THE HOOD MUSEUM OF ART DOES NOT RECOMMEND SPECIFIC CONSERVATORS. THIS LISTING IS MADE FOR PURPOSES OF INFORMATION ONLY.** Online directory of members of AIC (American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic works): www.conservation-us.org/membership/find-a-conservator GENERAL – Also see individual media below Straus Center for conservation and Technical Studies Harvard University Art Museums 32 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Paper, Objects, Textiles P: 617/495.2392 F: 617/495.0322 Website: www.harvardartmuseums.org Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum 25 Evans Way Boston, MA 02115 P: 617/566.1401 Paper, Objects, Textiles F: 617/278.5167 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gardnermuseum.org Vermont Museum and Gallery Alliance C/O Fairbanks Museum Referrals. Good source for general 1302 Main Street information on storage, packing, and St. Johnsbury, VT 05819 care of artwork. P: 802/751.8381 Williamstown Art Conservation Center, Inc. 227 South Street Williamstown, MA 02167 Paintings, paper, objects, furniture, P: 413/458.5741 sculpture, frames, analytical F: 413/458.2314 Email: [email protected] Website: www.williamstownart.org Worcester Art Museum 55 Salisbury Street Worcester, MA 01609 Paper, Paintings P: 508/799.4406 Email: [email protected] Website: www.worcesterart.org CONSERVATORS/RESTORERS Updated: 8/2015 General Continued Art Conservation Resource Center 262 Beacon Street, #4 Paintings, paper, photographs, textiles, Boston, MA 02116 objects and sculpture P: -

Conservation of Cultural and Scientific Objects

CHAPTER NINE 335 CONSERVATION OF CULTURAL AND SCIENTIFIC OBJECTS In creating the National Park Service in 1916, Congress directed it "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life" in the parks.1 The Service therefore had to address immediately the preservation of objects placed under its care. This chapter traces how it responded to this charge during its first 66 years. Those years encompassed two developmental phases of conservation practice, one largely empirical and the other increasingly scientific. Because these tended to parallel in constraints and opportunities what other agencies found possible in object preservation, a preliminary review of the conservation field may clarify Service accomplishments. Material objects have inescapably finite existence. All of them deteriorate by the action of pervasive external and internal agents of destruction. Those we wish to keep intact for future generations therefore require special care. They must receive timely and. proper protective, preventive, and often restorative attention. Such chosen objects tend to become museum specimens to ensure them enhanced protection. Curators, who have traditionally studied and cared for museum collections, have provided the front line for their defense. In 1916 they had three principal sources of information and assistance on ways to preserve objects. From observation, instruction manuals, and formularies, they could borrow the practices that artists and craftsmen had developed through generations of trial and error. They might adopt industrial solutions, which often rested on applied research that sought only a reasonable durability. And they could turn to private restorers who specialized in remedying common ills of damaged antiques or works of art. -

Integrating Archaeology and Conservation of Archaeology and Conservation the Past, Forintegrating the Future

SC 13357-2 11/30/05 2:39 PM Page 1 PROCEEDINGS PROCEEDINGS The Getty Conservation Institute The Conservation Los Angeles Theme of the 5th World Archaeological Congress Of the Past, for the Future: Washington, D.C. Printed in Canada June 2003 Integrating Archaeology and Conservation Of the Past, for the Future: Integrating Archaeology and Conservation The Getty Conservation Institute i-xii 1-4 13357 10/26/05 10:56 PM Page i Of the Past, for the Future: Integrating Archaeology and Conservation i-xii 1-4 13357 10/26/05 10:56 PM Page ii i-xii 1-4 13357 10/26/05 10:56 PM Page iii Of the Past, for the Future: Integrating Archaeology and Conservation Proceedings of the Conservation Theme at the 5th World Archaeological Congress, Washington, D.C., 22–26 June 2003 Edited by Neville Agnew and Janet Bridgland The Getty Conservation Institute Los Angeles i-xii 1-4 13357 10/26/05 10:56 PM Page iv The Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen, Director Jeanne Marie Teutonico, Associate Director, Field Projects and Science The Getty Conservation Institute works internationally to advance conserva- tion and to enhance and encourage the preservation and understanding of the visual arts in all of their dimensions—objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through scientific research; education and training; field projects; and the dissemination of the results of both its work and the work of others in the field. In all its endeavors, the Institute is committed to addressing unanswered questions and promoting the highest possible standards of conservation practice. -

LARA KAPLAN 5105 Kennett Pike OBJECTS CONSERVATOR Winterthur, DE 19735 [email protected]

Winterthur Museum LARA KAPLAN 5105 Kennett Pike Winterthur, DE 19735 OBJECTS CONSERVATOR [email protected] EDUCATION Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation, Winterthur, DE M.S./Certificate in Art Conservation, objects major – August 2003 Rice University, Houston, TX B.A. Art/Art History and Linguistics, cum laude – May 1997 CONSERVATION EXPERIENCE 7/19-Present: Objects Conservator; Affiliated Assistant Professor Winterthur Museum, Library and Gardens; Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC) – Winterthur, DE At Winterthur, preserving three-dimensional objects in the museum collection, conducting technical examinations and treatment, and consulting on proper handling, storage, transport, and exhibition requirements. For WUDPAC, leading the Organic Block portion of the 1st-year curriculum, covering plant materials, skin/leather, keratins, ivory, bone, and related materials, and plastics; supervising 2nd- and 3rd-year objects majors; serving on student advisory committees; teaching advanced seminars on specialized topics, including characterization and treatment of skin/leather artifacts, conservation of basketry, feathers, and plastics, ethical issues in the conservation of modern/contemporary collections and objects from indigenous cultures, and opening a conservation private practice. 1/05-Present: Freelance Conservator Baltimore, MD (1/05-12/18); Philadelphia, PA (1/19-Present) Working as an independent conservator for institutions, galleries, and private individuals. Services include examination, treatment, surveys, art historical research, and sampling/testing of art and artifacts made of a wide range of materials (glass, ceramics, stone, plaster, metals, lacquer, wood and other plant materials, skin and leather, horn, tortoiseshell, feather, ivory, bone, shell, rubber, and plastics), as well as consultation and preparing objects for storage, transportation, and exhibition. -

MCI Interns and Volunteers

MCI Weekly Highlight 13 August 2010 Understanding the American Experience, Valuing World Cultures , Unlocking the Mysteries of the Universe, Understanding and Sustaining a Biodiverse Planet The Museum Conservation Institute hosted 10 interns and volunteers this summer. These individuals significantly increase research and conservation treatment productivity at MCI. We would like to take the opportunity to acknowledge their contributions and wish them the best in their future endeavors. • In the Paintings Conservation Laboratory under the mentorship of Senior Paintings Conservator, Jia-sun Tsang, Laura King worked on Sam Gilliam’s Muse I from 1965 which is a stained acrylic painting, and James Aiken’s Swedish Cottage and Shakespeare Garden from 1959 which is an oil painting—both paintings from the Anacostia Community Museum. Allison Martin continued to work with Jia-sun Tsang on several paintings conservation-related projects. Rebecca Gieseking worked with Jia-sun on a manuscript based on a plastics conservation project that they began two years ago. • E. Keats Webb worked with Senior Conservator, Mel Wachowiak, on an in-depth exploration of 3D scanning, Quick Time Virtual Reality, High Definition digital video, and Reflectance Transformation Imaging. A publication is pending that will compare the strengths and weaknesses of the techniques in cultural heritage applications. • In the Textile Conservation Studio, Mary Ballard, Senior Textiles Conservator, oversaw the work of several intern projects focusing on the Black Fashion Museum collection acquired by the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Cathleen Zaret finished re-housing the McGee collection of garments,and will turn to repairs on a lovely honeymoon peignoir as she finishes her internship August 30. -

2011 Iic Student & Emerging Conservator Conference

2011 IIC STUDENT & EMERGING CONSERVATOR CONFERENCE CONSERVATION FUTURES AND RESPONSIBILITIES TRANSCRIPTS – 2 of 3 Session 2, Saturday 17th September “Planning a professional career how did the professionals get to where they are? How do they see conservation work and responsibilities changing over the coming years?” Moderator Adam M Klupś Adam M Klupś [Unrecorded preamble: My name is Adam M Klupś and I have recently graduated from UCL with a degree in History of Art with Material Studies. I am about to start my MA in Principles of Conservation here at the Institute. My plan is to become an archaeological conservator and I am using the word ‘plan’ on purpose. I am sure that many of you consider your professional ambitions as a plan, possibly still subject to change. It happens very often and entirely naturally that we get to the same point via different routes or end up being miles apart even though the starting point is the same. In today’s session I would like to think about the issue of planning in relation to a professional career in the field of conservation as it is today, in the 21st century. This will lead us to the question on the current state of the conservation discipline and new responsibilities that appear before us, we who are soon to become conservation professionals.] Introducing our speakers for this session: from the left is Bronwyn Ormsby, a Senior Conservation Scientist at Tate, who introduced me to the world of conservation science. Bronwyn also teaches at UCL and at the Courtauld Institute. Next to Bronwyn we have Duygu Camurcuoglu, originally from Turkey, now based in London. -

2018 Summit Program Abstracts

Safety and Cultural Heritage Summit: Preserving Our Heritage and Protecting Our Health 7 November 2018 – Smithsonian American Art Museum – Washington, DC Presentation Abstracts Rare but Significant Exposures: Treating Corroded Cadmium Plating in a Museum Setting Arianna Johnston, Objects Conservator; Anne McDonough, MD, MPH, Associate Director Occupational Health Services, Smithsonian Office of Safety, Health and Environmental Management This presentation will discuss the recent coordination between Smithsonian Office of Safety, Health, and Environmental Management (OSHEM) and the National Air and Space Museum Conservation Unit to treat toxic cadmium corrosion while prioritizing health and safety. While exploring the most expedient treatment methods for 650 pieces of cadmium‐plated hardware from a World War II‐era bomber, OSHEM was invited to conduct air monitoring as conservators tested two treatment methods. One of these treatment methods measured the concentration of airborne cadmium dust to be above the “action level” for an eight‐hour time‐weighted average, which initiated a medical surveillance program. This surveillance aimed to identify employees most at risk from chronic exposure to cadmium and to detect and prevent cadmium‐induced diseases. While the cadmium dust level detected during the test required further investigation and medical monitoring, it was determined that the frequency of the activity did not require annual medical surveillance. As part of this collaboration, safer treatment methods were chosen for the project, and medical baseline testing is now included as part of the onboarding process for new fellows, interns, and employees. This talk will discuss the best practice use of medical monitoring and surveillance for infrequent activities that may produce action level exposures. -

Bruno Pouliot (MAC 1983), Objects Conservator and Associate Professor, Winterthur/University of Delaware Program

Bruno Pouliot (MAC 1983), Objects Conservator and Associate Professor, Winterthur/University of Delaware Program Interviewed by Sophia Zweifel (MAC 2015) Throughout his career, Bruno Pouliot has made a meaningful impact on conservation communities across many countries and continents. After growing up in a small town in Québec, Bruno pursued a B.A. degree in Classical Archaeology at Laval University. During an excavation in Tunisia, Bruno became interested in conservation, and went on to complete the Master of Art Conservation Program at Queen’s University in 1983. In his early career, Bruno completed internships at the Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) in Ottawa, the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, the Fowler Museum at UCLA, and at conservation research centres in France and Germany. In 1985, his passion for travel inspired him to take on a short ICCROM teaching position in West Africa. His sense of adventure did not stop there, as he spent the next six years (from 1986 to 1991) in the Arctic, working as an Objects Conservator at the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre in Yellowknife. Bruno then moved to Montreal, and served as Objects Conservator, and later Head of Conservation, at the McCord Museum. Realizing his passion for teaching, Bruno left Montreal in 1997 to join the faculty at the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation as Objects Conservator and Assistant Professor. He now has a long legacy of students who have benefitted from his teaching, and his dedication was recognized in 2010 when he received the Sheldon & Caroline Keck Award for excellence in the education and training of conservation professionals. -

Forum #3 Summary December 4-5, 2014 Dallas Museum of Art “Charting the Digital Landscape of the Conservation Profession”

Forum #3 Summary December 4-5, 2014 Dallas Museum of Art “Charting the Digital Landscape of the Conservation Profession” A project of the Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (FAIC) January 27, 2015 This project was funded by grants from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Samuel H. Kress Foundation, and Getty Foundation Forum #3 Summary, page 1 Invited Participants: Max Anderson, Director, Dallas Museum of Art Connie Bodner, Supervisory Grants Management Specialist, Museum Services, IMLS Foekje Boersma, Project Manager, Managing Collection Environments Initiative, GCI Fran Bass, Associate Conservator for Objects, Dallas Museum of Art Tom Clareson, Senior Digital & Preservation Services Consultant, Lyrasis Kirk Cordell, Executive Director, NCPTT (NPS) Tiarna Doherty, Chief Conservator, Lunder Center, American Art, Smithsonian Institution Deena Engel, Professor, Department of Computer Science, NYU Martin Halbert, Dean of Libraries, University of North Texas; President, Educopia Institute Laura Hartman, Paintings Conservator, Dallas Museum of Art Arlen Heginbotham, Associate Conservator, Decorative Arts Conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum Unmil Karadkar, Assistant Professor, School of Information, University of Texas at Austin Dale Kronkright, Head of Conservation, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Mark Leonard, Chief Conservator, Dallas Museum of Art Michele Marincola, Professor of Conservation, Institute of Fine Arts, NYU Max Marmor, President, Samuel H. Kress Foundation Richard McCoy, Independent Art -

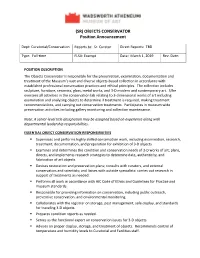

Objects Conservator Web Posting

(SR) OBJECTS CONSERVATOR Position Announcement Dept: Curatorial/Conservation Reports to: Sr. Curator Direct Reports: TBD Type: Full-time FLSA: Exempt Date: March 1, 2019 Rev. Date: POSITION DESCRIPTION The Objects Conservator is responsible for the preservation, examination, documentation and treatment of the Museum’s vast and diverse objects-based collection in accordance with established professional conservation practices and ethical principles. The collection includes sculpture, furniture, ceramics, glass, metal works, and 3-D modern and contemporary art. S/he oversees all activities in the conservation lab relating to 3-dimensional works of art including examination and analyzing objects to determine if treatment is required, making treatment recommendations, and carrying out conservation treatments. Participates in museum wide preservation activities including gallery monitoring and collection maintenance. Note: A senior-level title designation may be assigned based on experience along with departmental leadership responsibilities. ESSENTIAL OBJECT CONSERVATION RESPONSIBILITIES § Supervises and performs highly skilled conservation work, including examination, research, treatment, documentation, and preparation for exhibition of 3-D objects. § Examines and determines the condition and conservation needs of 3-D works of art; plans, directs, and implements research strategies to determine date, authenticity, and fabrication of art objects. § Devises restoration and preservation plans; consults with curators, and external conservators and scientists; and liaises with outside specialists; carries out research in support of treatments as needed. § Performs all work in accordance with AIC Code of Ethics and Guidelines for Practice and museum standards. § Responsible for providing information on conservation, including public outreach, preventive conservation, and environmental monitoring. § Collaborates with the registrar on storage, pest management, safe display, and standards for traveling 3-D objects. -

This Presentation

Art Conservation What is art conservation? • Art conservation is the field dedicated to preserving cultural property • Preventive and interventive • Conservation is an interdisciplinary field that relies heavily on chemistry, art history, history, anthropology, ethics, and art Laura Sankary cleans a porcelain plate during an internship at UD Art Conservation at the University of Delaware • Three programs • Undergraduate degree (BA or BS) • Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation or WUDPAC (MS) at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library near Wilmington, DE • Doctorate in Preservation Studies (PhD) Miriam-Helene Rudd cleans a painting during an internship with Joyce Hill Stoner at Winterthur Museum Undergraduate Degree in Art Conservation • Faculty members are all conservators and conservation scientists • On-site, hands-on internships, scientific, and materials courses (pre-requisites for graduate school) • Extensive networking opportunities for external summer and winter session internships Nick Fandaros reconstructs a large ceramic vessel from Papua New Guinea Each faculty member is a trained conservator or conservation scientist! Debra Hess Norris Dr. Jocelyn Alcántara- Brian Baade Maddie Hagerman Dr. Joyce Hill Stoner Nina Owczarek Photograph Conservator García Paintings Conservator Objects Conservator Paintings Conservator Objects Conservator Chair and Professor of Conservation Scientist Assistant Professor Instructor Edward F. and Elizabeth Goodman Assistant Professor Photograph Conservation Associate Professor Rosenberg