Protecting Cultural Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michelle Lynn Brown 44 Maryland Ave, Saranac Lake, NY 12983 (518) 524-0468 [email protected]

Michelle Lynn Brown 44 Maryland Ave, Saranac Lake, NY 12983 (518) 524-0468 [email protected] EDUCATION University of Vermont, Vermont Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit Ongoing PhD, Natural Resources Dissertation: “Effects of Forest Biomass Energy Production on Northern Forest Sustainability and Biodiversity” University of Vermont, Vermont Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit 2012 MS, Natural Resources Thesis: “Predicting Impacts of Future Human Population Growth and Development on Occupancy Rates and Landscape Carrying Capacity of Forest-Dependent Birds” Penn State University, Graduate GIS Certificate 2005 Binghamton University, State University of New York 2001 BS, Environmental Studies Concentration in Ecosystems, Magna Cum Laude TEACHING EXPERIENCE Instructor, Population Dynamics and Modeling, University of Vermont 2014 • Co-taught 30 graduate students and federal employees using a live online format Graduate Teaching Program Ongoing • Completed more than 50 hours of mentored teaching, observations, and workshops PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Conservation Scientist The Nature Conservancy, Adirondack Chapter 2007- Keene Valley, NY • Led regional team to integrate climate resilience into transportation infrastructure design (five states and three provinces) • Secured more than $1,200,000 to incorporate conservation objectives into New York State transportation planning and implementation; managed projects • Led ecological assessment and science strategy for 161,000-acre land protection project Conservation Planner The -

Core Conservation Courses (Finh-Ga.2101-2109)

Conservation Course Descriptions—Full List Conservation Center, Institute of Fine Arts Page 1 of 38, 2/05/2020 CORE CONSERVATION COURSES (FINH-GA.2101-2109) MATERIAL SCIENCE OF ART & ARCHAEOLOGY I FINH-GA.2101.001 [#reg. code] (Lecture, 3 points) Instructor Hours to be arranged Location TBD The course extends over two terms and is related to Technology and Structure of Works of Art I and II. Emphasis during this term is on problems related to the study and conservation of organic materials found in art and archaeology from ancient to contemporary periods. The preparation, manufacture, and identification of the materials used in the construction and conservation of works of art are studied, as are mechanisms of degradation and the physicochemical aspects of conservation treatments. Enrollment is limited to conservation students and other qualified students with the permission of the faculty of the Conservation Center. This course is required for first-year conservation students. MATERIAL SCIENCE OF ART & ARCHAEOLOGY II FINH-GA.2102.001 [#reg. code] (Lecture, 3 points) Instructor Hours to be arranged Location TBD The course extends over two terms and is related to Technology and Structure of Works of Art I and II. Emphasis during this term is on the chemistry and physics of inorganic materials found in art and archaeological objects from ancient to contemporary periods. The preparation, manufacture, and identification of the materials used in the construction and conservation of works of art are studied, as are mechanisms of degradation and the physicochemical aspects of conservation treatments. Each student is required to complete a laboratory assignment with a related report and an oral presentation. -

Conservation of Cultural and Scientific Objects

CHAPTER NINE 335 CONSERVATION OF CULTURAL AND SCIENTIFIC OBJECTS In creating the National Park Service in 1916, Congress directed it "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life" in the parks.1 The Service therefore had to address immediately the preservation of objects placed under its care. This chapter traces how it responded to this charge during its first 66 years. Those years encompassed two developmental phases of conservation practice, one largely empirical and the other increasingly scientific. Because these tended to parallel in constraints and opportunities what other agencies found possible in object preservation, a preliminary review of the conservation field may clarify Service accomplishments. Material objects have inescapably finite existence. All of them deteriorate by the action of pervasive external and internal agents of destruction. Those we wish to keep intact for future generations therefore require special care. They must receive timely and. proper protective, preventive, and often restorative attention. Such chosen objects tend to become museum specimens to ensure them enhanced protection. Curators, who have traditionally studied and cared for museum collections, have provided the front line for their defense. In 1916 they had three principal sources of information and assistance on ways to preserve objects. From observation, instruction manuals, and formularies, they could borrow the practices that artists and craftsmen had developed through generations of trial and error. They might adopt industrial solutions, which often rested on applied research that sought only a reasonable durability. And they could turn to private restorers who specialized in remedying common ills of damaged antiques or works of art. -

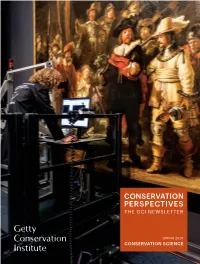

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES the Gci Newsletter

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES THE GCI NEWSLETTER SPRING 2020 CONSERVATION SCIENCE A Note from As this issue of Conservation Perspectives was being prepared, the world confronted the spread of coronavirus COVID-19, threatening the health and well-being of people across the globe. In mid-March, offices at the Getty the Director closed, as did businesses and institutions throughout California a few days later. Getty Conservation Institute staff began working from home, continuing—to the degree possible—to connect and engage with our conservation colleagues, without whose efforts we could not accomplish our own work. As we endeavor to carry on, all of us at the GCI hope that you, your family, and your friends, are healthy and well. What is abundantly clear as humanity navigates its way through this extraordinary and universal challenge is our critical reliance on science to guide us. Science seeks to provide the evidence upon which we can, collectively, make decisions on how best to protect ourselves. Science is essential. This, of course, is true in efforts to conserve and protect cultural heritage. For us at the GCI, the integration of art and science is embedded in our institutional DNA. From our earliest days, scientific research in the service of conservation has been a substantial component of our work, which has included improving under- standing of how heritage was created and how it has altered over time, as well as developing effective conservation strategies to preserve it for the future. For over three decades, GCI scientists have sought to harness advances in science and technology Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI Anna Flavin, Photo: to further our ability to preserve cultural heritage. -

BROMEC 36 Bulletin of Research on Metal Conservation

BROMEC 36 Bulletin of Research on Metal Conservation Editorial July 2016 BROMEC 36 contains seven abstracts on research covering archaeological, historic and modern metals conservation. They comprise a call for collaboration by a consortium in southern France that is endeavouring to remove copper staining from outdoor stone using non-toxic materials. Also, two projects from Brazil present their material diagnosis approaches to informing conservation strategies. The first focuses on contemporary metals used in the structures and finishes of architecture and sculpture, while the second is for an item of industrial heritage; a steamroller which features in the title image for this issue of BROMEC. Further ways of diagnosing materials and their degradation mechanisms are outlined in a Swiss abstract concerned with cans containing foodstuffs. This work will also be presented at ICOM-CC’s upcoming Metal 2016 conference in New Delhi: 26-30 September 2016. Updates on ongoing projects in France and Spain are given too. In France, a new shared laboratory has been established to progress the subcritical stabilisation method for archaeological iron and also for optimising protection by organic coatings of metallic artefacts exposed to air. In Spain, works on in situ Anglophone editor & translator: electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for evaluating protection by coatings and James Crawford [email protected] patinas have been extended to acquire larger data sets from heritage and over Francophone coeditor: multiple time intervals. Lastly, insights into comparing the efficacy of spraying and Michel Bouchard brushing Paraloid B-72 for protecting wrought iron are given in laboratory research mbouchard caraa.fr Francophone translators: from the United Kingdom. -

Center for Biodiversity and Conservation

Center for Biodiversity and Conservation Progress Update Spring 2021 Dear CBC Friends & Colleagues, Understanding life on Earth and how to sustain it for the future is the fundamental challenge of our time. For almost 30 years, the Center for Biodiversity and Conservation has been advancing research, strengthening human capacity, and creating connections to help the Museum meet this challenge. This past year has brought an unprecedented crisis, yet I am extremely proud of what our small team at the Center has achieved. The Year in Numbers 40 Publications 35 Peer-reviewed 29 Open access 6 With local partners 10 With students, interns, mentees 8 Awards, honors, or appointments 17 Presentations at professional meetings 27 Invited talks 28 Contributions to AMNH programs 12 Popular articles, media appearances or coverage 15 Funding proposals 8 With DEIJ dimensions/objectives 9 With external partners 23 Average number of interns, mentees, and trainees per semester 8 New software tools, modules and other resources produced (all open access) CBC Director of Biodiversity Informatics Research Dr. Mary Blair Notable and collaborators have been selected for new funding under NASA’s Ecological Forecasting Program to deepen and expand our awards and current NASA-funded collaboration with the Colombia Biodiversity appointments Observation Network. Dr. Blair and other scientists leading the CBC’s Machine Learning for Conservation projects are looking forward to collaborating with the Museum’s Department of Education on their new National Science Foundation (NSF) award focused on preparing high school students for careers in machine learning through mentored scientific research. The $1.48 million grant will span three years, and will expand opportunities for science-interested students to apply machine learning approaches to research in biology, including conservation biology. -

2011 Iic Student & Emerging Conservator Conference

2011 IIC STUDENT & EMERGING CONSERVATOR CONFERENCE CONSERVATION FUTURES AND RESPONSIBILITIES TRANSCRIPTS – 2 of 3 Session 2, Saturday 17th September “Planning a professional career how did the professionals get to where they are? How do they see conservation work and responsibilities changing over the coming years?” Moderator Adam M Klupś Adam M Klupś [Unrecorded preamble: My name is Adam M Klupś and I have recently graduated from UCL with a degree in History of Art with Material Studies. I am about to start my MA in Principles of Conservation here at the Institute. My plan is to become an archaeological conservator and I am using the word ‘plan’ on purpose. I am sure that many of you consider your professional ambitions as a plan, possibly still subject to change. It happens very often and entirely naturally that we get to the same point via different routes or end up being miles apart even though the starting point is the same. In today’s session I would like to think about the issue of planning in relation to a professional career in the field of conservation as it is today, in the 21st century. This will lead us to the question on the current state of the conservation discipline and new responsibilities that appear before us, we who are soon to become conservation professionals.] Introducing our speakers for this session: from the left is Bronwyn Ormsby, a Senior Conservation Scientist at Tate, who introduced me to the world of conservation science. Bronwyn also teaches at UCL and at the Courtauld Institute. Next to Bronwyn we have Duygu Camurcuoglu, originally from Turkey, now based in London. -

Tips for Talking to Scientists from the Executive Director, 3

JANUARY 2019 » VOL 44:1 INSIDE Tips for Talking to Scientists From the Executive Director, 3 AIC News, 7 By Corina Rogge, The Andrew W. Mellon Research Scientist at the Museum of RESEARCH & Fine Arts, Houston and the Menil Collection, and RATS Specialty Group Chair Annual Meeting News, 12 TECHNICAL ccess to conservation scientists is a luxury for many institutions, let STUDIES GROUP Aalone conservators working in private practice. However, colleges FAIC News, 13 COLUMN and universities abound with scientists and equipment and thus can be Emergency Programs, 13 a valuable resource for those in need of analysis. The issue becomes how Funding, 14 to communicate effectively with an academic scientist who is not accustomed to thinking Courses, 15 about or who lacks familiarity with materials used in the cultural heritage field. To help navigate these interactions, this “field guide” may help conservators communicate more effectively with JAIC News, 16 scientists. Allied Organizations, 18 What Are You Really Asking? Although this may seem like basic common sense, “What is this?” is one of the hardest questions Health & Safety, 19 for a scientist to answer because it is so unspecific. You know the problem that you’re dealing with and why you are reaching out for help, so be as specific as you can to contextualize your New Publications, 22 question. Contextualizing the question will provide the scientist with the information needed to frame the analytical approach required. For example, statements such as “I need to know People, 22 the type of varnish present on this painting to help figure out appropriate solvents to remove it” or “I need to know whether this taxidermy mount contains an arsenic-based pesticide and Conservation Graduate must therefore be handled with appropriate measures” are most effective on several levels. -

Participants Profiles

BRAINSTORM ON CONSERVATION SCIENCE ICCROM, Rome, 12-13 March 2012 PARTICIPANTS Catherine Antomarchi Collections Unit Director ICCROM Rome, Italy For over 20 years, Catherine has developed, planned, and ensured delivery of numerous courses and educational tools from ICCROM, the intergovernmental agency renowned for such work. During the 1990’s she was instrumental in the delivery of PREMA, Preventive Conservation for Museums in Africa, a comprehensive program of year long courses, in collaboration with English and French universities, designed in response to extensive on-site needs assessment, and consultation, followed by a plan of genuine capacity transfer. The result was the emergence of EPA and PMDA, self- sufficient agencies serving francophone and anglophone Africa. As a result of this work, she was awarded Honorary Member of the Cowrie Circle by the Commonwealth Associations of Museums. She has studied extensively the methods of effective education and training for professionals in museums, and has authored or co-authored 20 papers related to this subject. As the Director of the ICCROM Collections unit, organizing and delivering collections training programs throughout the world, Catherine applies her firm belief that training courses must provide true capacity transference, and that they must be part of a much larger strategy of related initiatives. She has taken personal responsibility for the risk assessment course as well as the affiliated development of support tools, all within a long term strategy to help museums around the world make better decisions about collection conservation. Sharon C ather Deputy Head, Conservation of Wall Painting Department The Courtauld Institute of Art London, United Kingdom Sharon Cather has taught all aspects of the conservation of wall painting at the Courtauld Institute of Art since 1985, when she jointly founded the MA programme. -

Conserving Textiles Studies in Honour of Ágnes Timár-Balázsy ICCROM Conservation Studies 7

iCCrom Conservation studies 7 Conserving Textiles studies in honour of Ágnes timÁr-BalÁzsy iCCrom Conservation studies 7 Conserving Textiles studies in honour of Ágnes timÁr-BalÁzsy Original Hungarian versiOn edited by: istván eri editOrial bOard: Judit b. Perjés, Katalin e. nagy, Márta Kissné bendefy, Petronella Mravik Kovács and eniko sipos Conserving Textiles: Studies in honour of Ágnes Timár-Balázsi ICCROM Conservation Studies 7 ISBN 92-9077-218-2 © ICCROM 2009. Authorized translation of the Hungarian edition © 2004 Pulszky Hungarian Museums Association (HMA). This translation is published and sold by permission of the Pulszky HMA, the owner of all rights to publish and sell the same. The publishers would like to record their thanks to Márta Kissné Bendefy for her immense help in the preparation of this volume, to Dinah Eastop for editing the English texts, and to Cynthia Rockwell for copy editing. ICCROM International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property Via di San Michele 13 00153 Rome, Italy www.iccrom.org Designed by Maxtudio, Rome Printed by Ugo Quintily S.p.A. In memoriam: Ágnes Timár-Balázsy (1948–2001) gnes Timár-Balázsy was an inspirational Ágnes became well known around the world as a teacher of conservation science and she will teacher of chemistry and of the scientific background be remembered as a joyful and passionate of textile conservation for professionals. She taught person, with vision, intelligence and the regularly on international conservation courses Áability and willingness to work very hard. She loved at ICCROM in Rome as well as at the Textile both teaching and travel and developed a network of Conservation Centre in Britain, the Abegg-Stiftung friends and colleagues all over the world. -

PLASTICS in PERIL Focus on Conservation of Polymeric Materials in Cultural Heritage

PLASTICS IN PERIL Focus on Conservation of Polymeric Materials in Cultural Heritage Virtual conference November 16th–19th, 2020 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS WELCOME TO: Plastics in Peril: Focus on conservation of polymeric materials in cultural heritage “Plastics in Peril” began life as two separate events, an in-person conference planned by University of Cambridge Museums, and a workshop planned by the Leibniz Association of Research Museums. COVID-19 forced the cancellation of in-person events, but opened up new and unforeseen opportunities to collaborate with colleagues further afi eld and build new relationships with them. So we are delighted to be able to off er for the fi rst time a conference hosted jointly by the Leibniz Association in Germany and University of Cambridge Museums in the UK. By combining our two events we are able to have a much bigger and richer programme, and by holding the event online we can reach a much larger audience than we could with an in-person event. Almost 1000 people have registered to attend this meeting live, from every continent in the world except Antarctica. Videos of most of the presentations will also be available to view online, for free, after the event. The programme for this conference focusses very much on practical solutions for managing plastics collections, whether they include artworks, domestic items or objects from the history of science and industry. Plastics have been incredibly useful to us over the last century, and are found in every part of our heritage. But as we know they also present a signifi cant threat to our environment. -

This Presentation

Art Conservation What is art conservation? • Art conservation is the field dedicated to preserving cultural property • Preventive and interventive • Conservation is an interdisciplinary field that relies heavily on chemistry, art history, history, anthropology, ethics, and art Laura Sankary cleans a porcelain plate during an internship at UD Art Conservation at the University of Delaware • Three programs • Undergraduate degree (BA or BS) • Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation or WUDPAC (MS) at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library near Wilmington, DE • Doctorate in Preservation Studies (PhD) Miriam-Helene Rudd cleans a painting during an internship with Joyce Hill Stoner at Winterthur Museum Undergraduate Degree in Art Conservation • Faculty members are all conservators and conservation scientists • On-site, hands-on internships, scientific, and materials courses (pre-requisites for graduate school) • Extensive networking opportunities for external summer and winter session internships Nick Fandaros reconstructs a large ceramic vessel from Papua New Guinea Each faculty member is a trained conservator or conservation scientist! Debra Hess Norris Dr. Jocelyn Alcántara- Brian Baade Maddie Hagerman Dr. Joyce Hill Stoner Nina Owczarek Photograph Conservator García Paintings Conservator Objects Conservator Paintings Conservator Objects Conservator Chair and Professor of Conservation Scientist Assistant Professor Instructor Edward F. and Elizabeth Goodman Assistant Professor Photograph Conservation Associate Professor Rosenberg