CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES the Gci Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michelle Lynn Brown 44 Maryland Ave, Saranac Lake, NY 12983 (518) 524-0468 [email protected]

Michelle Lynn Brown 44 Maryland Ave, Saranac Lake, NY 12983 (518) 524-0468 [email protected] EDUCATION University of Vermont, Vermont Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit Ongoing PhD, Natural Resources Dissertation: “Effects of Forest Biomass Energy Production on Northern Forest Sustainability and Biodiversity” University of Vermont, Vermont Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit 2012 MS, Natural Resources Thesis: “Predicting Impacts of Future Human Population Growth and Development on Occupancy Rates and Landscape Carrying Capacity of Forest-Dependent Birds” Penn State University, Graduate GIS Certificate 2005 Binghamton University, State University of New York 2001 BS, Environmental Studies Concentration in Ecosystems, Magna Cum Laude TEACHING EXPERIENCE Instructor, Population Dynamics and Modeling, University of Vermont 2014 • Co-taught 30 graduate students and federal employees using a live online format Graduate Teaching Program Ongoing • Completed more than 50 hours of mentored teaching, observations, and workshops PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Conservation Scientist The Nature Conservancy, Adirondack Chapter 2007- Keene Valley, NY • Led regional team to integrate climate resilience into transportation infrastructure design (five states and three provinces) • Secured more than $1,200,000 to incorporate conservation objectives into New York State transportation planning and implementation; managed projects • Led ecological assessment and science strategy for 161,000-acre land protection project Conservation Planner The -

Iaea Tecdoc Series Tecdoc Iaea @

IAEA-TECDOC-1803 IAEA-TECDOC-1803 IAEA TECDOC SERIES Trends of Synchrotron Radiation Applications in Cultural Heritage, Forensics and Materials Science Forensics Applications in Cultural Heritage, of Synchrotron Radiation Trends IAEA-TECDOC-1803 Trends of Synchrotron Radiation Applications in Cultural Heritage, Forensics and Materials Science @ TRENDS OF SYNCHROTRON RADIATION APPLICATIONS IN CULTURAL HERITAGE, FORENSICS AND MATERIALS SCIENCE The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN GEORGIA OMAN ALBANIA GERMANY PAKISTAN ALGERIA GHANA PALAU ANGOLA GREECE PANAMA ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA GUATEMALA PAPUA NEW GUINEA ARGENTINA GUYANA PARAGUAY ARMENIA HAITI PERU AUSTRALIA HOLY SEE PHILIPPINES AUSTRIA HONDURAS POLAND AZERBAIJAN HUNGARY PORTUGAL BAHAMAS ICELAND QATAR BAHRAIN INDIA REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA BANGLADESH INDONESIA ROMANIA BARBADOS IRAN, ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF RUSSIAN FEDERATION BELARUS IRAQ RWANDA BELGIUM IRELAND SAN MARINO BELIZE ISRAEL SAUDI ARABIA BENIN ITALY SENEGAL BOLIVIA, PLURINATIONAL JAMAICA SERBIA STATE OF JAPAN SEYCHELLES BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA JORDAN SIERRA LEONE BOTSWANA KAZAKHSTAN SINGAPORE BRAZIL KENYA SLOVAKIA BRUNEI DARUSSALAM KOREA, REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA BULGARIA KUWAIT SOUTH AFRICA BURKINA FASO KYRGYZSTAN SPAIN BURUNDI LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC SRI LANKA CAMBODIA REPUBLIC SUDAN CAMEROON LATVIA SWAZILAND CANADA LEBANON SWEDEN CENTRAL AFRICAN LESOTHO SWITZERLAND REPUBLIC LIBERIA SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC CHAD LIBYA TAJIKISTAN CHILE LIECHTENSTEIN THAILAND CHINA LITHUANIA THE FORMER YUGOSLAV -

Core Conservation Courses (Finh-Ga.2101-2109)

Conservation Course Descriptions—Full List Conservation Center, Institute of Fine Arts Page 1 of 38, 2/05/2020 CORE CONSERVATION COURSES (FINH-GA.2101-2109) MATERIAL SCIENCE OF ART & ARCHAEOLOGY I FINH-GA.2101.001 [#reg. code] (Lecture, 3 points) Instructor Hours to be arranged Location TBD The course extends over two terms and is related to Technology and Structure of Works of Art I and II. Emphasis during this term is on problems related to the study and conservation of organic materials found in art and archaeology from ancient to contemporary periods. The preparation, manufacture, and identification of the materials used in the construction and conservation of works of art are studied, as are mechanisms of degradation and the physicochemical aspects of conservation treatments. Enrollment is limited to conservation students and other qualified students with the permission of the faculty of the Conservation Center. This course is required for first-year conservation students. MATERIAL SCIENCE OF ART & ARCHAEOLOGY II FINH-GA.2102.001 [#reg. code] (Lecture, 3 points) Instructor Hours to be arranged Location TBD The course extends over two terms and is related to Technology and Structure of Works of Art I and II. Emphasis during this term is on the chemistry and physics of inorganic materials found in art and archaeological objects from ancient to contemporary periods. The preparation, manufacture, and identification of the materials used in the construction and conservation of works of art are studied, as are mechanisms of degradation and the physicochemical aspects of conservation treatments. Each student is required to complete a laboratory assignment with a related report and an oral presentation. -

Protecting Cultural Heritage

Protecting Cultural Heritage Reflections on the Position of conservation science. Important players in this field, Science in Multidisciplinary which readily address interactivity and networking, are the recently started Episcon project in the European Approaches Community’s Marie Curie program3 and the five- 4 by Jan Wouters year-old EU-Artech project. The goal of Episcon is to develop the first generation of actively formed ver the past 40 years, scientific research activ- conservation scientists at the Ph.D.-level in Europe. ities in support of the conservation and resto- EU-Artech provides access, research, and technology Oration of objects and monuments belonging for the conservation of European cultural heritage, to the world’s cultural heritage, have grown in number including networking among 13 European infrastruc- and quality. Many institutes specifically dedicated to tures operating in the field of artwork conservation. the study and conservation of cultural heritage have The present absence of a recognized, knowledge- emerged. Small dedicated laboratories have been based identity for conservation science or conserva- installed in museums, libraries, and archives, and, tion scientists may lead to philosophical and even more recently, university laboratories are showing linguistic misunderstandings within multidisciplinary increased interest in this field. consortiums created to execute conservation projects. This paper discusses sources of misunderstandings, However, no definition has been formulated to iden- a suggestion for more transparent language when tify the specific tasks, responsibilities, and skills of a dealing with the scientific term analysis, elements to conservation scientist or of conservation science. This help define conservation science, and the benefits is contradictory to the availability of a clear Definition for conservation scientists of becoming connected to of the Profession of a Conservator-Restorer, published worldwide professional networks. -

The Archive of Renowned Architectural Photographer

DATE: August 18, 2005 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE GETTY ACQUIRES ARCHIVE OF JULIUS SHULMAN, WHOSE ICONIC PHOTOGRAPHS HELPED TO DEFINE MODERN ARCHITECTURE Acquisition makes the Getty one of the foremost centers for the study of 20th-century architecture through photography LOS ANGELES—The Getty has acquired the archive of internationally renowned architectural photographer Julius Shulman, whose iconic images have helped to define the modern architecture movement in Southern California. The vast archive, which was held by Shulman, has been transferred to the special collections of the Research Library at the Getty Research Institute making the Getty one of the most important centers for the study of 20th-century architecture through the medium of photography. The Julius Shulman archive contains over 260,000 color and black-and-white negatives, prints, and transparencies that date back to the mid-1930s when Shulman began his distinguished career that spanned more than six decades. It includes photographs of celebrated monuments by modern architecture’s top practitioners, such as Richard Neutra, Frank Lloyd Wright, Raphael Soriano, Rudolph Schindler, Charles and Ray Eames, Gregory Ain, John Lautner, A. Quincy Jones, Mies van der Rohe, and Oscar Niemeyer, as well as images of gas stations, shopping malls, storefronts, and apartment buildings. Shulman’s body of work provides a seminal document of the architectural and urban history of Southern California, as well as modernism throughout the United States and internationally. The Getty is planning an exhibition of Shulman’s work to coincide with the photographer’s 95th birthday, which he will celebrate on October 10, 2005. The Shulman photography archive will greatly enhance the Getty Research Institute’s holdings of architecture-related works in its Research Library, which -more- Page 2 contains one of the world’s largest collections devoted to art and architecture. -

Spring 2015 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

theGETTY A WORLD OF ART, RESEARCH, CONSERVATION, AND PHILANTHROPY | Spring 2015 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE theGETTY Spring 2014 TABLE OF President’s Message 3 by James Cuno President and CEO, the J. Paul Getty Trust CONTENTS New and Noteworthy 4 Earlier this year I attended the World Economic Forum in Keeping it Modern 6 Davos, Switzerland, during which government officials and corporate, education, and cultural leaders gather to explore Darkroom Alchemists Reinvent Photography 14 the economic and political prospects for the coming year. I gave a presentation about the ways in which digital technol- A Sense of Place in the City of Angels 20 ogy is transforming the museum experience—from initial dis- covery, to visiting, to research and collaboration, to the ways Thousands of Rare Books on your Desktop 24 in which visitors can engage more deeply with the collection through digital resources. This issue of The Getty expands Book Excerpt: J. M. W. Turner: Painting Set Free 27 on our previous coverage of how the Getty is “going digital” through projects like the HistoricPlacesLA initiative from the New from Getty Publications 28 Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) and the many digital fac- ets that are accessible to researchers and patrons around the From The Iris 30 world from the Getty Research Institute Library. Last month, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti joined GCI New Acquisition 31 Director Tim Whalen, Foundation Director Deborah Marrow, and me to launch HistoricPlacesLA, the city’s groundbreaking Getty Events 32 new system for mapping and inventorying historic resources in Los Angeles. HistoricPlacesLA contains information gath- Exhibitions 34 ered through SurveyLA—a citywide survey of LA’s significant historic resources—a public/private partnership between the From the Vault 35 City of Los Angeles and the Getty, including both the GCI and Foundation. -

Press Release

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: June 5, 2019 MEDIA CONTACTS: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Julie Jaskol Getty Communications (310) 440-7607 [email protected] J. PAUL GETTY TRUST BOARD OF TRUSTEES ELECTS DR. DAVID L. LEE AS CHAIR Dr. David L. Lee has served on the Board since 2009; he begins his four-year term as chair on July 1 LOS ANGELES—The Board of Trustees of the J. Paul Getty Trust today announced it has elected Dr. David L. Lee as its next chair of the Board. “We are delighted that Dr. Lee will lead the Getty Board of Trustees as we embark on many exciting initiatives,” said Getty President James Cuno. “Dr. Lee’s involvement with the international community, his experience in higher education and philanthropy, and his strong financial acumen has served the Getty well. We look forward to his leadership.” Dr. Lee was appointed to the Getty Board of Trustees in 2009. Dr. Lee will serve a four-year term as chair of the 15-member group that includes leaders in art, education, and business who volunteer their time and expertise on behalf of the Getty. “Through its extensive research, conservation, exhibition and education programs, the Getty’s work has made a powerful impact not only on the Los Angeles region, but around the world,” Dr. Lee said. “I am honored to be part of such a generous, inspiring organization that makes a lasting difference and is a source of great pride for our community.” The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax: 310 440 7722 Dr. -

Conservation of Cultural and Scientific Objects

CHAPTER NINE 335 CONSERVATION OF CULTURAL AND SCIENTIFIC OBJECTS In creating the National Park Service in 1916, Congress directed it "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life" in the parks.1 The Service therefore had to address immediately the preservation of objects placed under its care. This chapter traces how it responded to this charge during its first 66 years. Those years encompassed two developmental phases of conservation practice, one largely empirical and the other increasingly scientific. Because these tended to parallel in constraints and opportunities what other agencies found possible in object preservation, a preliminary review of the conservation field may clarify Service accomplishments. Material objects have inescapably finite existence. All of them deteriorate by the action of pervasive external and internal agents of destruction. Those we wish to keep intact for future generations therefore require special care. They must receive timely and. proper protective, preventive, and often restorative attention. Such chosen objects tend to become museum specimens to ensure them enhanced protection. Curators, who have traditionally studied and cared for museum collections, have provided the front line for their defense. In 1916 they had three principal sources of information and assistance on ways to preserve objects. From observation, instruction manuals, and formularies, they could borrow the practices that artists and craftsmen had developed through generations of trial and error. They might adopt industrial solutions, which often rested on applied research that sought only a reasonable durability. And they could turn to private restorers who specialized in remedying common ills of damaged antiques or works of art. -

Press Image Sheet

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: September 17, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Julie Jaskol Getty Communications (310) 440-7607 [email protected] GETTY TO DEVOTE $100 MILLION TO ADDRESS THREATS TO THE WORLD’S ANCIENT CULTURAL HERITAGE Global initiative will enlist partners to raise awareness of threats and create effective conservation and education strategies Participants in the 2014 Mosaikon course Conservation and Management of Archaeo- logical Sites with Mosaics conduct a condition survey exercise of the Achilles Mosaic at the Paphos Archeological Park, Paphos, Cyprus. Continued work at Paphos will be undertaken as part of Ancient Worlds Now. Los Angeles – The J. Paul Getty Trust will embark on an unprecedented and ambitious $100- million, decade-long global initiative to promote a greater understanding of the world’s cultural heritage and its universal value to society, including far-reaching education, research, and conservation efforts. The innovative initiative, Ancient Worlds Now: A Future for the Past, will explore the interwoven histories of the ancient worlds through a diverse program of ground-breaking The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax: 310 440 7722 scholarship, exhibitions, conservation, and pre- and post- graduate education, and draw on partnerships across a broad geographic spectrum including Asia, Africa, the Americas, the Middle East, and Europe. “In an age of resurgent populism, sectarian violence, and climate change, the future of the world’s common heritage is at risk,” said James Cuno, president and CEO of the J. -

Julius Shulman: Modernity and the Metropolis (October 11, 2005–January 22, 2006)

RELATED EVENTS Julius Shulman: Modernity and the Metropolis (October 11, 2005–January 22, 2006) RELATED EVENTS AND PUBLICATIONS All events are free but reservations are required. For more information or to make a reservation, please call 310-440-7300 or visit www.getty.edu. CONVERSATION Julius Shulman discusses his work, the exhibition, and the Julius Shulman Photography Archive with Wim de Wit, head, Special Collections and Visual Resources, and curator of architectural drawings, Getty Research Institute. Friday, October 14, 2005, 4:00-5:30pm Museum Lecture Hall LECTURES "Shooting Time: Julius Shulman and the Image of Contemporary Architecture" Sylvia Lavin, chair, Architecture and Urban Design, University of California, Los Angeles. Thursday, November 3, 2005, 4:00–6:00 p.m. Getty Research Institute Lecture Hall "A Continual Becoming: Rudolph Schindler's Discordant Modernism" Thomas S. Hines, professor, History and Architecture, University of California, Los Angeles. Thursday, December 1, 2005, 4:00–6:00 p.m. Getty Research Institute Lecture Hall FILM SCREENING AND DISCUSSION “Left Coast Modernism: Architecture and Urban Form in Los Angeles” Reyner Banham’s documentary Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles (1972, 52 min.) is the British architectural historian’s critical examination of Los Angeles as it was developing into a major metropolitan city at the end of the mid-century Modern movement, a period that photographer Julius Shulman documented so eloquently. Panelists include Amy Murphy, assistant professor, School of Architecture, University of Southern California, and Ed Dimendberg, associate professor, Film and Media Studies and Visual Studies, University of California, Irvine. Wednesday, December 7, 2005, 7:30 p.m. -

Getty and Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage Announce Major Enhancements to Ghent Altarpiece Website

DATE: August 20, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE IMAGES OF THE RESTORED ADORATION OF THE LAMB AND MORE: GETTY AND ROYAL INSTITUTE FOR CULTURAL HERITAGE ANNOUNCE MAJOR ENHANCEMENTS TO GHENT ALTARPIECE WEBSITE Closer to Van Eyck offers a 100 billion-pixel view of the world-famous altarpiece, to be enjoyed from home http://closertovaneyck.kikirpa.be/ The Lamb of God on the central panel, from left to right: before restoration (with the 16th-century overpaint still present), during restoration (showing the van Eycks’ original Lamb from 1432 before retouching), after retouching (the final result of the restoration) LOS ANGELES AND BRUSSELS – Since 2012, the website Closer to Van Eyck has made it possible for millions around the globe to zoom in on the intricate, breathtaking details of the Ghent Altarpiece, one of the most celebrated works of art in the world. More than a quarter million people have taken advantage of the opportunity so far in 2020, and website visitorship has increased by 800% since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, underscoring the potential for modern digital technology to increase access to masterpieces from all eras and learn more about them. The Getty and the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA, Brussels, Belgium), in collaboration with the Gieskes Strijbis Fund in Amsterdam, are giving visitors even more ways to explore this monumental work of art from afar, with the launch today of a new version of the site that includes images of recently restored sections of the paintings as well as new videos and education materials. Located at St. -

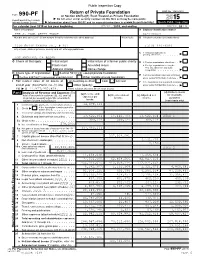

Attach to Your Tax Return. Department of the Treasury Attachment Sequence No

Public Inspection Copy Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2015 or tax year beginning 07/01 , 2015, and ending 06/30, 20 16 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE J. PAUL GETTY TRUST 95-1790021 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 1200 GETTY CENTER DR., # 401 (310) 440-6040 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here LOS ANGELES, CA 90049 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the Address change Name change 85% test, check here and attach computation H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: CashX Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination end of year (from Part II, col.