4 Politics, Portraits, and Love

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

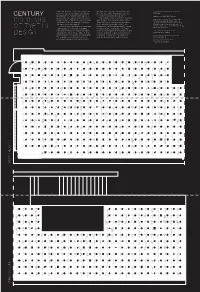

Century 100 Years of Type in Design

Bauhaus Linotype Charlotte News 702 Bookman Gilgamesh Revival 555 Latin Extra Bodoni Busorama Americana Heavy Zapfino Four Bold Italic Bold Book Italic Condensed Twelve Extra Bold Plain Plain News 701 News 706 Swiss 721 Newspaper Pi Bodoni Humana Revue Libra Century 751 Boberia Arriba Italic Bold Black No.2 Bold Italic Sans No. 2 Bold Semibold Geometric Charlotte Humanist Modern Century Golden Ribbon 131 Kallos Claude Sans Latin 725 Aurora 212 Sans Bold 531 Ultra No. 20 Expanded Cockerel Bold Italic Italic Black Italic Univers 45 Swiss 721 Tannarin Spirit Helvetica Futura Black Robotik Weidemann Tannarin Life Italic Bailey Sans Oblique Heavy Italic SC Bold Olbique Univers Black Swiss 721 Symbol Swiss 924 Charlotte DIN Next Pro Romana Tiffany Flemish Edwardian Balloon Extended Bold Monospaced Book Italic Condensed Script Script Light Plain Medium News 701 Swiss 721 Binary Symbol Charlotte Sans Green Plain Romic Isbell Figural Lapidary 333 Bank Gothic Bold Medium Proportional Book Plain Light Plain Book Bauhaus Freeform 721 Charlotte Sans Tropica Script Cheltenham Humana Sans Script 12 Pitch Century 731 Fenice Empire Baskerville Bold Bold Medium Plain Bold Bold Italic Bold No.2 Bauhaus Charlotte Sans Swiss 721 Typados Claude Sans Humanist 531 Seagull Courier 10 Lucia Humana Sans Bauer Bodoni Demi Bold Black Bold Italic Pitch Light Lydian Claude Sans Italian Universal Figural Bold Hadriano Shotgun Crillee Italic Pioneer Fry’s Bell Centennial Garamond Math 1 Baskerville Bauhaus Demian Zapf Modern 735 Humanist 970 Impuls Skylark Davida Mister -

Coexistence of Mythological and Historical Elements

COEXISTENCE OF MYTHOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL ELEMENTS AND NARRATIVES: ART AT THE COURT OF THE MEDICI DUKES 1537-1609 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Greek and Roman examples of coexisting themes ........................................................................ 6 1. Cosimo’s Triumphal Propaganda ..................................................................................................... 7 Franco’s Battle of Montemurlo and the Rape of Ganymede ........................................................ 8 Horatius Cocles Defending the Pons Subicius ................................................................................. 10 The Sacrificial Death of Marcus Curtius ........................................................................................... 13 2. Francesco’s parallel narratives in a personal space .............................................................. 16 The Studiolo ................................................................................................................................................ 16 Marsilli’s Race of Atalanta ..................................................................................................................... 18 Traballesi’s Danae .................................................................................................................................... 21 3. Ferdinando’s mythological dream ............................................................................................... -

Raphael's Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (1514-16) in the Context of Il Cortegiano

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Paragon/Paragone: Raphael's Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (1514-16) in the Context of Il Cortegiano Margaret Ann Southwick Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1547 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O Margaret Ann Southwick 2005 All Rights Reserved PARAGONIPARAGONE: RAPHAEL'S PORTRAIT OF BALDASSARE CASTIGLIONE (1 5 14-16) IN THE CONTEXT OF IL CORTEGIANO A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Cornmonwealtli University. MARGARET ANN SOUTHWICK M.S.L.S., The Catholic University of America, 1974 B.A., Caldwell College, 1968 Director: Dr. Fredrika Jacobs Professor, Department of Art History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December 2005 Acknowledgenients I would like to thank the faculty of the Department of Art History for their encouragement in pursuit of my dream, especially: Dr. Fredrika Jacobs, Director of my thesis, who helped to clarify both my thoughts and my writing; Dr. Michael Schreffler, my reader, in whose classroom I first learned to "do" art history; and, Dr. Eric Garberson, Director of Graduate Studies, who talked me out of writer's block and into action. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Portrait of Bianca Capello (1548 - 1587)

FLORENTINE SCHOOL, C. 1580 Portrait of Bianca Capello (1548 - 1587) oil on canvas 121 x 86.5 cm (47⅝ x 34 in) Provenance: Private Collection, Vienna. Literature: Elizabeth J. M. van Kessel, The Social Lives of Paintings in Sixteenth-Century Venice, PhD dissertation, Leiden University, 2011, p. 209, fig. 82. HIS STRIKING three-QUARter-length portrait depicts Bianca Capello (1541-1587), one of the most celebrated women of the Cinquecento. Since her death the fame, scandal, and intrigue that surrounded her life have continued to fascinate historians and biographers, and this Timposing portrait captures the wealth and majesty that helped make her such a compelling figure. Bianca was born into a wealthy and powerful Venetian family, but at the age of fifteen caused scandal by running away and secretly marrying Pietro Bonaventuri, a Florentine accountant who had been working at the Salviati bank in Venice. Bianca’s father, Bartolomeo, was predictably furious and managed to have Bonaventuri banned from Venice, but his attempts to send his daughter to a monastery were resisted. The young couple settled in Florence where Bianca soon attracted the attention of Grand Prince Francesco de’ Medici (1541 – 1587), heir to the Tuscan throne. Bianca became Francesco’s mistress, despite his marriage to Joanna of Austria (1547-1578), and in 1572 Pietro was murdered ‘with the knowledge and, probably, approval of Francesco’.¹ Bianca and Francesco continued their relationship even when the latter became Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1574, and they had a son, Antonio, in 1576. The affair was common knowledge in Florence but was generally unpopular given the regard that Joanna of Austria was held, due to her devout nature and the political and economic alliances that the Hapsburg princess provided.² However, Joanna unexpectedly died in 1578, and two months later Francesco and Bianca married in secret. -

Suggested Fonts List

Suggested Fonts List This is a list of some fonts our designers have available to use when designing your book. This is only a sample of some of the most popular fonts; they have thousands of others to choose from as well. For your convenience, we have marked each font as being appropriate for body text or display text. Body Text fonts are meant for the main body text of your book—paragraphs, lists, etc. These fonts are designed to be easier on the eyes for smoother reading. Display Text fonts are meant for chapter titles, subtitles, etc. They are often “fancier” fonts, such as script or handwriting. We advise against using these as main body text, as they are intended for short strings of text and can become difficult to read in long paragraphs. Last updated 6/6/2014 B = Body Text: Fonts meant for the main body text of your book. D = Display Text: Fonts meant for chapter titles, etc. We advise against using these as main body text, as they are intended for short strings of text and can become difficult to read in long paragraphs. Font Name Font Styles Font Sample BD Abraham Lincoln Regular The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. 1234567890 Adobe Caslon Pro Regular The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. Italic 1234567890 Semibold Semibold Italic Bold Bold Italic Adobe Garamond Pro Regular The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. Italic 1234567890 Semibold Semibold Italic Bold Bold Italic Adobe Jenson Pro Light The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. -

EUI Working Papers

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION EUI Working Papers HEC 2010/02 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION Moving Elites: Women and Cultural Transfers in the European Court System Proceedings of an International Workshop (Florence, 12-13 December 2008) Giulia Calvi and Isabelle Chabot (eds) EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE , FLORENCE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION Moving Elites: Women and Cultural Transfers in the European Court System Proceedings of an International Workshop (Florence, 12-13 December 2008) Edited by Giulia Calvi and Isabelle Chabot EUI W orking Paper HEC 2010/02 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. ISSN 1725-6720 © 2010 Giulia Calvi and Isabelle Chabot (eds) Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract The overall evaluation of the formation of political decision-making processes in the early modern period is being transformed by enriching our understanding of political language. This broader picture of court politics and diplomatic networks – which also relied on familial and kin ties – provides a way of studying the political role of women in early modern Europe. This role has to be studied taking into account the overlapping of familial and political concerns, where the intersection of women as mediators and coordinators of extended networks is a central feature of European societies. -

Typeface Classification Serif Or Sans Serif?

Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Serif or Sans Serif? ABCDEFG ABCDEFG abcdefgo abcdefgo Adobe Jenson DIN Pro Book Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Typeface or font? ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Regular ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Italic TYPEFACE FAMILY ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Bold ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Bold Italic Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Timeline Blackletter Humanist Old Style Transitional Modern Bauhaus Digital (aka Venetian) sans serif 1450 1460- 1716- 1700- 1780- 1920- 1980-present 1470 1728 1775 1880 1960 Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif The model for the first movable types was Blackletter (also know as Block, Gothic, Fraktur or Old English), a heavy, dark, at times almost illegible — to modern eyes — script that was common during the Middle Ages. from I Love Typography http://ilovetypography.com/2007/11/06/type-terminology-humanist-2/ Typography 1: : Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif Types based on blackletter were soon superseded by something a little easier Humanist (also refered to Venetian).. ABCDEFG ABCDEFG > abcdefg abcdefg Adobe Jenson Fette Fraktur Typography 1: : Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif The Humanist types (sometimes referred to as Venetian) appeared during the 1460s and 1470s, and were modelled not on the dark gothic scripts like textura, but on the lighter, more open forms of the Italian humanist writers. The Humanist types were at the same time the first roman types. Typography 1: : Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif Characteristics 1. -

History of Moveable Type

History of Moveable Type Johannes Gutenberg invented Moveable Type and the Printing Press in Germany in 1440. Moveable Type was first made of wood and replaced by metal. Example of moveable type being set. Fonts were Type set on a printing press. organized in wooden “job cases” by Typeface, Caps and Lower Case, and Point Size. Typography Terms Glyphs – letters (A,a,B,b,C,c) Typeface – The aesthetic design of an alphabet. Helvetica, Didot, Times New Roman Type Family – The range of variations and point size available within one Typeface. Font (Font Face) – The traditional term for the complete set of a typeface as it relates to one point size (Font Face: Helvetica, 10 pt). This would include upper and lower case glyphs, small capitals, bold and italic. After the introduction of the computer, the word Font is now used synonymously with the word Typeface, i.e. “What font are you using? Helvetica!” Weight – the weight of a typeface is determined by the thickness of the character outlines relative to their height (Hairline, Thin, Ultra-light, Extra-light, Light, Book, Regular, Roman, Medium, Demi-bold, Semi-bold, Bold, Extra-bold, Heavy, Black, Extra-black, Ultra-black). Point Size – the size of the typeface (12pt, 14pt, 18pt). Points are the standard until of typographic measurement. 12 points = 1 pica, 6 picas = 72 points = 1 inch. (Example right) A general rule is that body copy should never go below 10pt and captions should never be less than 8pt. Leading – or line spacing is the spacing between lines of type. In metal type composition, actual pieces of lead were inserted between lines of type on the printing press to create line spacing. -

The Corsini Collection: a Window on Renaissance Florence Exhibition Labels

The Corsini Collection: A Window on Renaissance Florence Exhibition labels © Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2017 Reproduction in part or in whole of this document is prohibited without express written permission. The Corsini Family Members of the Corsini family settled in Florence in the middle of the 13th century, attaining leading roles in government, the law, trade and banking. During that time, the Republic of Florence became one of the mercantile and financial centres in the Western world. Along with other leading families, the Corsini name was interwoven with that of the powerful Medici until 1737, when the Medici line came to an end. The Corsini family can also claim illustrious members within the Catholic Church, including their family saint, Andrea Corsini, three cardinals and Pope Clement XII. Filippo Corsini was created Count Palatine in 1371 by the Emperor Charles IV, and in 1348 Tommaso Corsini encouraged the foundation of the Studio Fiorentino, the University of Florence. The family’s history is interwoven with that of the city and its citizens‚ politically, culturally and intellectually. Between 1650 and 1728, the family constructed what is the principal baroque edifice in the city, and their remarkable collection of Renaissance and Baroque art remains on display in Palazzo Corsini today. The Corsini Collection: A Window on Renaissance Florence paints a rare glimpse of family life and loyalties, their devotion to the city, and their place within Florence’s magnificent cultural heritage. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki is delighted that the Corsini family have generously allowed some of their treasures to travel so far from home. -

Norberto Gramaccini Petrucci, Manutius Und Campagnola Die Medialisierung Der Künste Um 1500

Norberto Gramaccini Petrucci, Manutius und Campagnola Die Medialisierungder Künste um 1500 Die Jahre um 1500 waren für die Medialisierung der Künste und Wissenschaften von entscheidender Bedeutung.1 Am 15.Mai 1501 brachte in Venedig der aus Fossombrone gebürtige Musikdrucker Ottaviano dei Petrucci (1466–1539) mitseinemmusikalischen BeraterPetrusCastellanus das Harmonicemusices OdhecatonA(RISM 15011)heraus: Es ist das erste im Typendruckverfahren hergestellte Buch in mehrstimmigen Mensuralnoten, enthaltend 100drei- und vierstimmige Chansons der bekanntesten zeitgenössischen Komponisten –die meisten Franzosen und Flamen.2 Bereits 1498 hatte Petrucci beim veneziani- schen Senat ein Gesuch gestellt, das ihm als Erfnder ein Monopol für die Dauer von 20 Jahren zusichern sollte: »… chome aprimo Inventore che niuno altro nel dominio de Vostra Signoria possi stampare Canto fgurado …per anni vinti«.3 Dem Erstling folgten gleichgeartete Publikationen (Canti B, Canti C), die ei- nen Hinweis liefern, dass Petruccis vorrangiges Ziel in den ersten Jahren sei- ner Herausgebertätigkeit (bis 1504)darin bestand, nicht die sakrale, sondern 1Hans Blumenberg, Die Lesbarkeit der Welt,Frankfurt 1983;David McKitterick, Print, Manuscript and the Search for Order, 1450–1830,Cambridge 2004,S.109. 2Helen Hewitt und Isabel Pope, Petrucci. Harmonice Musices Odhecaton A,New York 1978. Das Datum 15/V/1501geht aus der Widmung an Girolamo Donato hervor. Für eine andere Datierung, David Fallows, »Petrucci’s Canti Volumes: Scope and Repertory«, in: Basler Jahrbuch für Historische Musikpraxis 25: Musik –Druck –Musikdruck. 500Jahre Ottaviano Petrucci (2001), S.39–52: S.41.ZuCastellanus,dem »magistercapelle«der Kirche SS.Giovanni ePaolo, den die Zeitgenossen als »arte musice monarcha« bezeichneten, Bonnie J. Blackburn, »Petrucci’s Venetian Editor: Petrus Castellanus and His Musical Garden«, in: Musica Disciplina 40 (1995), S.15–41: S.25.Zuden späten Quellen, die Petrucci auch als Besitzer mehrerer Papiermühlen ausweisen, Teresa M. -

Patrician Lawyers in Quattrocento Venice

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Servants of the Republic: Patrician lawyers in Quattrocento Venice. Jones, Scott Lee How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Jones, Scott Lee (2010) Servants of the Republic: Patrician lawyers in Quattrocento Venice.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42517 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Swansea University Prifysgol Abertawe Servants of the Republic: Patrician Lawyers inQuattrocento Venice Scott Lee Jones Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2010 ProQuest Number: 10805266 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted.