Raphael's Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (1514-16) in the Context of Il Cortegiano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

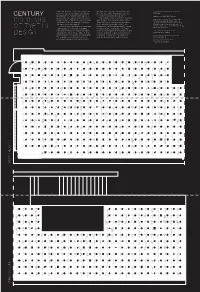

Century 100 Years of Type in Design

Bauhaus Linotype Charlotte News 702 Bookman Gilgamesh Revival 555 Latin Extra Bodoni Busorama Americana Heavy Zapfino Four Bold Italic Bold Book Italic Condensed Twelve Extra Bold Plain Plain News 701 News 706 Swiss 721 Newspaper Pi Bodoni Humana Revue Libra Century 751 Boberia Arriba Italic Bold Black No.2 Bold Italic Sans No. 2 Bold Semibold Geometric Charlotte Humanist Modern Century Golden Ribbon 131 Kallos Claude Sans Latin 725 Aurora 212 Sans Bold 531 Ultra No. 20 Expanded Cockerel Bold Italic Italic Black Italic Univers 45 Swiss 721 Tannarin Spirit Helvetica Futura Black Robotik Weidemann Tannarin Life Italic Bailey Sans Oblique Heavy Italic SC Bold Olbique Univers Black Swiss 721 Symbol Swiss 924 Charlotte DIN Next Pro Romana Tiffany Flemish Edwardian Balloon Extended Bold Monospaced Book Italic Condensed Script Script Light Plain Medium News 701 Swiss 721 Binary Symbol Charlotte Sans Green Plain Romic Isbell Figural Lapidary 333 Bank Gothic Bold Medium Proportional Book Plain Light Plain Book Bauhaus Freeform 721 Charlotte Sans Tropica Script Cheltenham Humana Sans Script 12 Pitch Century 731 Fenice Empire Baskerville Bold Bold Medium Plain Bold Bold Italic Bold No.2 Bauhaus Charlotte Sans Swiss 721 Typados Claude Sans Humanist 531 Seagull Courier 10 Lucia Humana Sans Bauer Bodoni Demi Bold Black Bold Italic Pitch Light Lydian Claude Sans Italian Universal Figural Bold Hadriano Shotgun Crillee Italic Pioneer Fry’s Bell Centennial Garamond Math 1 Baskerville Bauhaus Demian Zapf Modern 735 Humanist 970 Impuls Skylark Davida Mister -

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520)

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520) The Artist as Universal Man and Individual Genius By Susan Behrends Frank, Ph.D. Associate Curator for Research The Phillips Collection What are the new ideas behind the Italian High Renaissance? • Commitment to monumental interpretation of form with the human figure at center stage • Integration of form and space; figures actually occupy space • New medium of oil allows for new concept of luminosity as light and shadow (chiaroscuro) in a manner that allows form to be constructed in space in a new way • Physiological aspect of man developed • Psychological aspect of man explored • Forms in action • Dynamic interrelationship of the parts to the whole • New conception of the artist as the universal man and individual genius who is creative in multiple disciplines Michelangelo The Artists of the Italian High Renaissance Considered Universal Men and Individual Geniuses Raphael- Self-Portrait Leonardo da Vinci- Self-Portrait Michelangelo- Pietà- 1498-1500 St. Peter’s, Rome Leonardo da Vinci- Mona Lisa (Lisa Gherardinidi Franceso del Giacondo) Raphael- Sistine Madonna- 1513 begun c. 1503 Gemäldegalerie, Dresden Louvre, Paris Leonardo’s Notebooks Sketches of Plants Sketches of Cats Leonardo’s Notebooks Bird’s Eye View of Chiana Valley, showing Arezzo, Cortona, Perugia, and Siena- c. 1502-1503 Storm Breaking Over a Valley- c. 1500 Sketch over the Arno Valley (Landscape with River/Paesaggio con fiume)- 1473 Leonardo’s Notebooks Studies of Water Drawing of a Man’s Head Deluge- c. 1511-12 Leonardo’s Notebooks Detail of Tank Sketches of Tanks and Chariots Leonardo’s Notebooks Flying Machine/Helicopter Miscellaneous studies of different gears and mechanisms Bat wing with proportions Leonardo’s Notebooks Vitruvian Man- c. -

Baldassare Castiglione's Love and Ideal Conduct

Chapter 1 Baldassare Castiglione’s B OOK OF THE COURTIER: Love and Ideal Conduct Baldassare Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier was quite possibly the single most popular secular book in sixteenth century Europe, pub- lished in dozens of editions in all major European languages. The Courtier is a complex text that has many reasons for its vast popular- ity. Over the years it has been read as a guide to courtly conduct, a meditation on the nature of service, a celebration of an elite com- munity, a reflection on power and subjection, a manual on self- fashioning, and much else besides. But The Courtier must also be seen as a book about love. The debates about love in The Courtier are not tangential to the main concerns of the text; they are funda- mental to it. To understand the impact of The Courtier on discourses of love, one must place the text’s debates about love in the context of the Platonic ideas promulgated by Ficino, Bembo, and others, as well as the practical realities of sexual and identity politics in early modern European society. Castiglione’s dialogue attempts to define the perfect Courtier, but this ideal figure of masculine self-control is threatened by the instability of romantic love. Castiglione has Pietro Bembo end the book’s debates with a praise of Platonic love that attempts to redefine love as empowering rather than debasing, a practice of self-fulfillment rather than subjection. Castiglione’s Bembo defines love as a solitary pursuit, and rejects the social in favor of the individual. -

Ministero Per I Beni E Le Attività Culturali E Per Il Turismo Archivio Di Stato Di Genova

http://www.archiviodistatogenova.beniculturali.it Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali e per il turismo Archivio di Stato di Genova Instructiones et relationes Inventario n. 11 Regesti a cura di Elena Capra, Giulia Mercuri, Roberta Scordamaglia Genova, settembre 2020, versione 1.1 - 1 - http://www.archiviodistatogenova.beniculturali.it ISTRUZIONI PER LA RICHIESTA DELLE UNITÀ ARCHIVISTICHE Nella richiesta occorre indicare il nome del fondo archivistico e il numero della busta: quello che nell’inventario è riportato in neretto. Ad esempio per consultare 2707 C, 87 1510 marzo 20 Lettere credenziali a Giovanni Battista Lasagna, inviato in Francia. Tipologia documentaria: Lettere credenziali. Autorità da cui l’atto è emanato: Consiglio degli Anziani. Località o ambito di pertinenza: Francia. Persone menzionate: Giovanni Battista Lasagna. occorre richiedere ARCHIVIO SEGRETO 2707 C SUGGERIMENTI PER LA CITAZIONE DELLE UNITÀ ARCHIVISTICHE Nel citare la documentazione di questo fondo, ferme restando le norme adottate nella sede editoriale di destinazione dello scritto, sarà preferibile indicare la denominazione completa dell’istituto di conservazione e del fondo archivistico seguite dal numero della busta, da quello del documento e, se possibile, dall’intitolazione e dalla data. Ad esempio per citare 2707 C, 87 1510 marzo 20 Lettere credenziali a Giovanni Battista Lasagna, inviato in Francia. Tipologia documentaria: Lettere credenziali. Autorità da cui l’atto è emanato: Consiglio degli Anziani. Località o ambito di pertinenza: Francia. Persone menzionate: Giovanni Battista Lasagna. è bene indicare: Archivio di Stato di Genova, Archivio Segreto, b. 2707 C, doc. 87 «Lettere credenziali a Giovanni Battista Lasagna, inviato in Francia» del 20 marzo 1510. - 2 - http://www.archiviodistatogenova.beniculturali.it SOMMARIO Nota archivistica p. -

Olga Zorzi Pugliese Castiglione's the Book of the Courtier (Il Libro Del

138 Book Reviews Olga Zorzi Pugliese Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier (Il Libro del Cortegiano): A Classic in the Making Viaggio d’Europa 10. Naples: Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, 2008. Pp 382. The five extant manuscripts of Baldassare Castiglione’s Libro del Cortegiano, docu- menting what Olga Zorzi Pugliese terms his “propensity for endless revision,” offer an unique opportunity to trace the stylistic and ideological development of one of the most influential books of the entire early modern period. For the fifteen years prior to its publication in 1528, as Castiglione’s own career path intersected with the trajectory of the crises of the Italian peninsula that culminated in the Sack of Rome, the courtier and diplomat continuously rewrote his ambitious treatise. An invaluable addition to Amadeo Quondam’s recent work on the textual history of the Cortegiano, Pugliese’s stimulating monograph is the fruit of a research project that exploited modern database technology to collate and search all five manuscripts. The extent of the divergences between consecutive drafts, a corollary of the manner in which Castiglione excised, shifted, revised, and reinstated individual passages over a series of manuscripts, has made it difficult for past scholars to track the complexity of his writing process. Vittorio Cian established the basic chronological order of the manu- scripts in the first half of the twentieth century, but the identification and analysis of specific variants remain an ongoing concern. Given the limited access provided by Castiglione’s descendants in Mantua to the autograph material in the family archive, comprising fragments of the first draft, the starting point of most contemporary criti- cism has been Ghino Ghinassi’s 1968 edition of the so-called seconda redazione that records the intermediate stage in the evolution of the treatise. -

Suggested Fonts List

Suggested Fonts List This is a list of some fonts our designers have available to use when designing your book. This is only a sample of some of the most popular fonts; they have thousands of others to choose from as well. For your convenience, we have marked each font as being appropriate for body text or display text. Body Text fonts are meant for the main body text of your book—paragraphs, lists, etc. These fonts are designed to be easier on the eyes for smoother reading. Display Text fonts are meant for chapter titles, subtitles, etc. They are often “fancier” fonts, such as script or handwriting. We advise against using these as main body text, as they are intended for short strings of text and can become difficult to read in long paragraphs. Last updated 6/6/2014 B = Body Text: Fonts meant for the main body text of your book. D = Display Text: Fonts meant for chapter titles, etc. We advise against using these as main body text, as they are intended for short strings of text and can become difficult to read in long paragraphs. Font Name Font Styles Font Sample BD Abraham Lincoln Regular The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. 1234567890 Adobe Caslon Pro Regular The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. Italic 1234567890 Semibold Semibold Italic Bold Bold Italic Adobe Garamond Pro Regular The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. Italic 1234567890 Semibold Semibold Italic Bold Bold Italic Adobe Jenson Pro Light The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. -

BALDASSARRE CASTIGLIONE E RAFFAELLO VOLTI E MOMENTI DELLA VITA DI CORTE a Cura Di Vittorio Sgarbi E Elisabetta Soletti

PROGETTO MOSTRA BALDASSARRE CASTIGLIONE E RAFFAELLO VOLTI E MOMENTI DELLA VITA DI CORTE a cura di Vittorio Sgarbi e Elisabetta Soletti Urbino, Palazzo Ducale, Sale del Castellare 18 luglio - 1 novembre 2020 Nell’anno raffaellesco, la città di Urbino intende celebrare con una importante mostra Bal- dassarre Castiglione, figura di primo piano nel clima culturale e nel quadro politico dei primi decenni del Cinquecento. Figlio di Cristoforo Castiglione e di Aloisia Gonzaga, egli nasce a Casatico (Mantova) nel 1478. Nel 1490 viene mandato dal padre a Milano dove si forma la sua ampia cultura classica e umanistica alla scuola di Giorgio Merula e di Demetrio Calcondila, e le lingue e le lettera- ture classiche, in particolare il greco, rimangono le predilette dallo scrittore come testimo- niano le lettere e l’inventario della sua ricca biblioteca. Dopo la morte del padre, 1499, rientra a Mantova dove inizia la sua carriera diplomatica al servizio di Francesco Gonzaga. Nel 1504 si trasferisce a Urbino presso la corte di Guidobaldo di Montefeltro. Durante gli anni urbinati compie numerose missioni, tra cui quella del 1506 in cui si reca in Inghilterra presso Enrico VII. Dal 1513 al 1516 in qualità di ambasciatore del duca di Urbino si stabilisce a Roma du- rante il papato di Leone X, e in quel periodo si rinsaldarono i legami di amicizia e di affinità intellettuale che lo univano ai protagonisti, artisti e letterati, della vita culturale di quegli anni fin dalla stagione urbinate, tra cui P. Bembo, L. di Canossa, A. Beazzano, Raffaello, B. Dovizi da Bibbiena, G. G. -

Paul MAGDALINO Domaines De Recherche Adresse Personnelle

Paul MAGDALINO Professeur émérite de l’Université de St Andrews (Ecosse) Distinguished Research Professor, Koç University, Istanbul Membre de l’Académie Britannique Domaines de recherche Culture littéraire et religieuse de Constantinople Mentalités et représentation du pouvoir Urbanisme métropolitain et provincial Adresse personnelle 2 route de Volage, 01420, Corbonod, France Tél. 04 57 05 10 54 Curriculum vitae Né le 10 mai 1948 Etudes à Oxford, 1967-1977 Doctorat (DPhil) 1977 Enseignant (Maître de conférences, professeur associé, professeur), University of Saint Andrews, 1977-2009 Professeur à l’Université Koç d’Istanbul, 2004-2008 et 2010-2014 Fellow à Dumbarton Oaks, 1974-1975, 1994, 2013, 2015 Andrew Mellon Fellow, Catholic University of America, 1976-1977 A. v. Humboldt- Stipendiat, Frankfurt (1980-1981), Munich (1983), Berlin (2013) Professeur invité, Harvard University, 1995-1996 Directeur d’études invité, EPHE (1997, 2007), EHESS (2005) Chercheur invité à Dumbarton Oaks, 2006 Membre de l’Académie britannique depuis 2002 Membre correspondant de l’Institut de recherches byzantines de l’Université de Thessalonique (depuis 2010) Comités scientifiques et éditoriaux 1992 –Collection 'The Medieval Mediterranean', Brill 1993– Committee for the British Academy project on the Prosopography of the Byzantine Empire. 2001–7 Senior Fellows Committee, Dumbarton Oaks, Program in Byzantine Studies 2002 – Collection ‘Oxford Studies in Byzantium', Oxford University Press. 2006- La Pomme d’or, Geneva, chief editor 2007 – Comoité editorial de la revue Byzantinische Zeitschrift 2013-2014 – Editorial board of Koç University Press Publications Ouvrages 1976 (en collaboration avec Clive Foss) Rome and Byzantium (Oxford, 1976) 1991 Tradition and Transformation in Medieval Byzantium (Aldershot 1992) 1993 The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 1143-1180 (Cambridge, 1993). -

The Uses of Melancholy Among Military Nobles in Late Elizabethan England

10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2014/QM/04 36 Andreas Schlüter Humouring the Hero: The Uses of Melancholy among Military Nobles in Late Elizabethan England The interest of this article is twofold: fi rst, to aggressive foreign policy against Spain that establish and explore the intricate connection involved England with military on the continent between two key concepts in the fashioning of from the mid-1570s (“Leicester-Walsing ham English military nobles: the hero and melan- alliance”, Adams 25 and passim). The queen choly; and second, to explain their usages and herself referred to Sidney once as “le plus ac- usefulness in the last decades of the sixteenth compli gentilhomme de l’Europe” (Sidney, Cor- century, when both terms were used a lot more respondence II 999). He travelled Europe exten- frequently than ever before in the English lan- sively and brought many ideas and practices of guage (see, for hero, Simpson et al. 171 and the Mediterranean Renaissance and of the Euro- Low 23–24, and for melancholy, Babb 73). It is pean republic of letters into the practical life and possible to link this increase at least partially to behaviour of his generation of fellow court hope- the advance ment of one particular social fi gura- fuls, such as Walter Raleigh, Robert Devereux, tion1: the generation of young courtiers of Queen the 2nd Earl of Essex, and Fulke Greville. In this Elizabeth I who were born around 1560 and climate of “intellectual bombardment” by human- stepped into the courtly sphere in the 1580s and ist ideas as well as by Calvinist beliefs (Waller 1590s. -

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

Portrait of Elisabetta Gonzaga oil on wood, 52.50 x 37.30 cm Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, 1503 – 1504 ca. Like the painting depicting the Young Man with an Apple, this painting dates from Raffaello’s younger years, when he attended and served the court of Urbino. Raffaello was still just a child when his father Giovanni Santi, who under Duke Federico was the intellectual of the court and trusted on all matters artistic, held a theatrical play to celebrate the wedding of Guidobaldo, the Duke of Urbino’s heir, to Elisabetta Gonzaga. The painting arrived in the Medici collections, and thence to the Uffizi, as part of the dowry for Vittoria della Rovere’s wedding in 1631. It depicts the young woman dressed richly in clothes woven with gold, characterised by a refined, aristocratic elegance. A headdress in the portentous form of a scorpion rests on the lady’s forehead. The depiction of the landscape in the background is particularly poetic, with the light of the rising sun touching the strips of cloud in the sky and the rocky path over to the right. Young Man with an Apple painting on wood, 47.40 x 35.30 cm Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, 1503 – 1504 ca. Arriving in Florence from Urbino as part of Vittoria della Rovere’s dowry upon her marriage to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, this painting probably depicts a member of the Urbino court, perhaps the teenaged figure of Francesco Maria della Rovere himself. The boy is presented to us in the role of Paris. Like the hero in the myth, he holds the symbolic fruit in his right hand, destined for the most beautiful of the ladies who we must imagine competing before him. -

Motherhood and the Identity Formation of Masculinities in Sixteenth-Century “Erudite Comedy”

MOTHERHOOD AND THE IDENTITY FORMATION OF MASCULINITIES IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY “ERUDITE COMEDY” A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Yael Manes February 2010 © 2010 Yael Manes MOTHERHOOD AND THE IDENTITY FORMATION OF MASCULINITIES IN SIXTEENTH CENTURY “ERUDITE COMEDY” Yael Manes, Ph. D. Cornell University 2010 The commedia erudita (erudite comedy) is a five-act drama that is written in the vernacular and regulated by unity of time and place. It was conceived and reached its mature form in Italy during the first half of the sixteenth century. Erudite comedies were composed for audiences from the elite classes and performed in private settings. Since the plots dramatized the lives of contemporary, sixteenth-century urban dwellers, this genre of drama reflects many of the issues that preoccupied the elite classes during this period: the art of identity formation, the nature, attributes, and legitimacy of those who claim the authority to rule, and the relationship between power and gender, age, and experience. The dissertation analyzes five comedies: Ludovico Ariosto’s I suppositi (1509), Niccolò Machiavelli’s Mandragola (1518) and Clizia (1525), Antonio Landi’s Il commodo (1539), and Giovan Maria Cecchi’s La stiava (1546). These plays represent and critique idealized visions of patriarchal masculinity among the elite of Renaissance Italy through an engagement with the problems that maternity and mothering present to patriarchal ideology and identity. By unpacking the ways in which patriarchal masculinity is articulated in response to the challenges of maternal femininity, this dissertation gives a rich account of the gender order and the ways in which it was being problematized during the Italian Renaissance. -

The Marriage of True Minds

THE MARRIAGE OF TRUE MINDS Of the Rise and Fall of the Idealized Conception of Friendship in the Renaissance Von der Gemeinsamen Fakultät für Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Hannover zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) genehmigte Dissertation von ROBIN HODGSON, M. A., geboren am 21.06.1969 in Neustadt in Holstein 2003 Referent: Prof. Dr. Gerd Birkner Korreferenten: Prof. Dr. Dirk Hoeges Prof. Dr. Beate Wagner-Hasel Tag der Promotion: 30.10.2003 ABSTRACT (DEUTSCH) Gegenstand der vorliegenden Untersuchung ist der Freundschaftsbegriff der Renaissance, der seinen Ursprung wesentlich in der antiken Philosophie hat, seine Darstellungsweisen in der europäischen (insbesondere der englischen und italienischen) Literatur des fünfzehnten und sechzehnten Jahrhunderts, und der Wandel, dem dieser beim Epochenwechsel zur Aufklärung im siebzehnten Jahrhundert unterworfen war. Meine Arbeit vertritt die Hypothese, dass sich die Konzeptionen der verschiedenen Formen zwischenmenschlicher Beziehung die sich spätestens seit dem achtzehnten Jahrhundert etablieren konnten, auf die konzeptionellen Veränderungen des Freund- schaftsbegriffs und insbesondere auf den Wandel des Begriffsverständnisses von Freundschaft und Liebe während der Renaissance und des sich anschließenden Epochenwechsels zurückführen lassen. Um diese Hypothese zu verifizieren, habe ich daher nach einer kurzen Übersicht über die konzeptionellen Ursprünge des frühneuzeitlichen Freundschaftsbegriffs zunächst das Wesen der primär auf den philosophischen