Save Our Ships! Navigation on the High Seas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708

international journal of military history and historiography 39 (2019) 7-33 IJMH brill.com/ijmh Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708 Caleb Karges* Concordia University Irvine, California [email protected] Abstract The Austrian and British alliance in the Western Mediterranean from 1703 to 1708 is used as a case study in the problem of getting allies to cooperate at the strategic and operational levels of war. Differing grand strategies can lead to disagreements about strategic priorities and the value of possible operations. However, poor personal rela- tions can do more to wreck an alliance than differing opinions over strategy. While good personal relations can keep an alliance operating smoothly, it is often military necessity (and the threat of grand strategic failure) that forces important compro- mises. In the case of the Western Mediterranean, it was the urgent situation created by the Allied defeat at Almanza that forced the British and Austrians to create a work- able solution. Keywords War of the Spanish Succession – Coalition Warfare – Austria – Great Britain – Mediter- ranean – Spain – Strategy * Caleb Karges obtained his MLitt and PhD in Modern History from the University of St An- drews, United Kingdom in 2010 and 2015, respectively. His PhD thesis on the Anglo-Austrian alliance during the War of the Spanish Succession received the International Commission of Military History’s “André Corvisier Prize” in 2017. He is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Concordia University Irvine in Irvine, California, usa. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/24683302-03901002Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 03:43:06AM via free access <UN> 8 Karges 1 Introduction1 There were few wars in European history before 1789 as large as the War of the Spanish Succession. -

Early Maritime Navigation Unit Plan

EARLY MARITIME NAVIGATION UNIT PLAN Compelling How did advances in marine navigation, from the 13th century C.E. through the 18th century Question C.E., help to catapult Western Europe into global preeminence? C3 Historical Thinking Standards – D2.His.1.9-12. Evaluate how historical events and developments were shaped by unique circumstances of time and place as well as broader historical contexts. Standards C3 Historical Thinking Standards – D2.His.2.9-12. and Analyze change and continuity in historical eras. Practices Common Core Content Standards – CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.9-10.1.B Develop claim(s) and counterclaims fairly, supplying data and evidence for each while pointing out the strengths and limitations of both claim(s) and counterclaims in a discipline-appropriate form and in a manner that anticipates the audience's knowledge level and concerns. Staging the How do advances in marine navigation technology help nations develop and sustain world Question influence? Supporting Supporting Supporting Supporting Question 1 Question 2 Question 3 Question 4 Why has the sea been What is navigation and How does being posed How did STEM confer crucial to the fate of what special challenges with a challenge lead us to advantages to a society’s nations, empires, and does the sea pose to innovation and progress? ability to navigate the civilizations? travelers? world’s oceans? Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task 1 Performance Task 2 Performance Task 3 Performance Task 4 1) Look at the planet’s 1) In pairs ask your 1) Compass Lesson Plan 1) Drawing connections to physical geography, partner to draw you a (Lesson is located below the last three questions, all the Print Documents) build an argument that map from school to a view the Longitude video the sea was better at specific location in your Discover how the (07:05 min) connecting cultures town. -

Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708

international journal of military history and historiography 39 (2019) 7-33 IJMH brill.com/ijmh Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708 Caleb Karges* Concordia University Irvine, California [email protected] Abstract The Austrian and British alliance in the Western Mediterranean from 1703 to 1708 is used as a case study in the problem of getting allies to cooperate at the strategic and operational levels of war. Differing grand strategies can lead to disagreements about strategic priorities and the value of possible operations. However, poor personal rela- tions can do more to wreck an alliance than differing opinions over strategy. While good personal relations can keep an alliance operating smoothly, it is often military necessity (and the threat of grand strategic failure) that forces important compro- mises. In the case of the Western Mediterranean, it was the urgent situation created by the Allied defeat at Almanza that forced the British and Austrians to create a work- able solution. Keywords War of the Spanish Succession – Coalition Warfare – Austria – Great Britain – Mediter- ranean – Spain – Strategy * Caleb Karges obtained his MLitt and PhD in Modern History from the University of St An- drews, United Kingdom in 2010 and 2015, respectively. His PhD thesis on the Anglo-Austrian alliance during the War of the Spanish Succession received the International Commission of Military History’s “André Corvisier Prize” in 2017. He is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Concordia University Irvine in Irvine, California, usa. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/24683302-03901002Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 04:24:08PM via free access <UN> 8 Karges 1 Introduction1 There were few wars in European history before 1789 as large as the War of the Spanish Succession. -

“Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708

international journal of military history and historiography 39 (2019) 7-33 IJMH brill.com/ijmh Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708 Caleb Karges* Concordia University Irvine, California [email protected] Abstract The Austrian and British alliance in the Western Mediterranean from 1703 to 1708 is used as a case study in the problem of getting allies to cooperate at the strategic and operational levels of war. Differing grand strategies can lead to disagreements about strategic priorities and the value of possible operations. However, poor personal rela- tions can do more to wreck an alliance than differing opinions over strategy. While good personal relations can keep an alliance operating smoothly, it is often military necessity (and the threat of grand strategic failure) that forces important compro- mises. In the case of the Western Mediterranean, it was the urgent situation created by the Allied defeat at Almanza that forced the British and Austrians to create a work- able solution. Keywords War of the Spanish Succession – Coalition Warfare – Austria – Great Britain – Mediter- ranean – Spain – Strategy * Caleb Karges obtained his MLitt and PhD in Modern History from the University of St An- drews, United Kingdom in 2010 and 2015, respectively. His PhD thesis on the Anglo-Austrian alliance during the War of the Spanish Succession received the International Commission of Military History’s “André Corvisier Prize” in 2017. He is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Concordia University Irvine in Irvine, California, usa. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/24683302-03901002Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 05:14:25AM via free access <UN> 8 Karges 1 Introduction1 There were few wars in European history before 1789 as large as the War of the Spanish Succession. -

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76518-3 — the Making of the Modern Admiralty C

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76518-3 — The Making of the Modern Admiralty C. I. Hamilton Index More Information Index Accountant-General, 60; of the Navy Arbuthnot, Charles, 97–8 (from 1832): 65, 125, 138, 146, Army Staff, 222 189–93, 295 (see also estimates); Arnold-Forster, H. O., 198, 217 staff, 164, 188, 192 Asquith, H. H., 224 administrative board, 31 Assistant Secretary for Finance Duties Admiralty (see also Admiralty Office; (see also Secretariat), 192 Board of Admiralty; Childers, H. C. E.; Aube, H.-L.-T., 172 First and Second (Permanent) Auckland, George Eden, Earl of, 119, 134 Secretaries; Geddes, E.; Goschen, Awdry, Richard, 191, 201, 205 George; Graham, Sir James; ‘mob from the North’; Naval Staff; Navy Bacon, Sir Reginald, (Kt. 1916), 215 Board; Navy Pay Office; Principal Baddeley, Vincent, (Kt. 1921), 205, 206, 259 Officers; Private Office; Victualling Balfour, A. J., 237, 238 Board; Secretariat; Sick and Hurt Ballard, G. A., 222, 223 Office; Sixpenny Office; Transport Bank of England, 28 Office; War Staff): administration/ Barham, Lord, see Middleton, Charles policy divide, 266–7, 275, 279, 288, Barnaby, Nathaniel (Kt. 1885), 136, 162, 307; attacks on, 312; civil–military 173, 194–5 division in (see also Godfrey, John), Barrow, John (cr. baronet, 1835) (see also 68–9, 279, 289, 297–302, 313, 314; Second Secretary): 6, 12, 52, 57, 63; committees, 110–11, 120–3, 186–9, administration and policy of, 41, 51, 215; communications, 176, 220, 64, 68–9, 75, 93, 100–1, 103, 152, 248–50; demobilisation, 274, 276; 163; and Benthamism, 54; and development, 2–3, 23, 234–6; J. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

Edward Hawke Locker and the Foundation of The

EDWARD HAWKE LOCKER AND THE FOUNDATION OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF NAVAL ART (c. 1795-1845) CICELY ROBINSON TWO VOLUMES VOLUME II - ILLUSTRATIONS PhD UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART DECEMBER 2013 2 1. Canaletto, Greenwich Hospital from the North Bank of the Thames, c.1752-3, NMM BHC1827, Greenwich. Oil on canvas, 68.6 x 108.6 cm. 3 2. The Painted Hall, Greenwich Hospital. 4 3. John Scarlett Davis, The Painted Hall, Greenwich, 1830, NMM, Greenwich. Pencil and grey-blue wash, 14¾ x 16¾ in. (37.5 x 42.5 cm). 5 4. James Thornhill, The Main Hall Ceiling of the Painted Hall: King William and Queen Mary attended by Kingly Virtues. 6 5. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: King William and Queen Mary. 7 6. James Thornhill, Detail of the upper hall ceiling: Queen Anne and George, Prince of Denmark. 8 7. James Thornhill, Detail of the south wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of William III at Torbay. 9 8. James Thornhill, Detail of the north wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of George I at Greenwich. 10 9. James Thornhill, West Wall of the Upper Hall: George I receiving the sceptre, with Prince Frederick leaning on his knee, and the three young princesses. 11 10. James Thornhill, Detail of the west wall of the Upper Hall: Personification of Naval Victory 12 11. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: British man-of-war, flying the ensign, at the bottom and a captured Spanish galleon at top. 13 12. ‘The Painted Hall’ published in William Shoberl’s A Summer’s Day at Greenwich, (London, 1840) 14 13. -

The Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre Wish You a Very Happy Christmas and a Prosperous New Year News and Events Odette Buchanan, Friends’ Secretary

The Newsletter of the Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre Issue Number 12: November 2008 £2.00; free to members Christmas Number and Special issue to mark the 90th Anniversary of the World War One Armistice In memory of Frederick Charles Wellard, grandfather of the new FOMA Membership Secretary, Betty Cole. The wooden cross, pictured, is a rare image of how the war graves appeared before their replacement by the now familiar rows of white stone. Frederick was killed at Arras, France, in August 1917. The front line diary records, ‘16/8/17 Normal trench routine. Trenches deepened where necessary. Enemy active with pineapples. S. Major Wellard killed. C.Q.M.S. Blackstock wounded (afterwards died).’ Three days later the battalion was relieved. Fred left a widow and five young children, three of whom, including Betty’s mother, Ivy, were sent to orphanages. More of Frederick’s story can be read inside. The Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre wish you a very happy Christmas and a prosperous New Year News and Events Odette Buchanan, Friends’ Secretary At the 2008 FOMA AGM, it was decided that members should take on all the clerical responsibilities of the organisation, especially as we are all over the age of consent (some more so than others). In a moment of mental aberration I agreed to take on the role of Secretary. Aeons ago I had been paid to be the secretary to the Overseas Sales Director of a multi-national company and had had recent voluntary secretarial experience with another Friends group which I helped found. -

The Quest for Longitude

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contacts: Garland Scott, (202) 675-0342, [email protected] Esther French, (202) 675-0326, [email protected] Press Tour: Wednesday, March 18, 10:30 am Reservations requested, [email protected] New Exhibition—Ships, Clocks & Stars: The Quest for Longitude The solution to one of the greatest technical challenges of the eighteenth century Produced by the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London Proudly sponsored by United Technologies Corporation On exhibit March 19 – August 23, 2015 Washington, DC— For centuries, longitude (east-west position) was a matter of life and death at sea. Ships that went off course had no way to re-discover their longitude. With no known location, they might smash into underwater obstacles or be forever lost at sea. The award-winning exhibition, Ships, Clocks & Stars: The Quest for Longitude, produced by the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London, celebrates the 300th anniversary of the British Longitude Act of 1714, which offered huge rewards for any practical way to determine longitude at sea. The longitude problem was so difficult that—despite that incentive—it took five decades to solve it. Through extraordinary, historic materials—many from the collection of the National Maritime Museum—the exhibition tells the story of the clockmakers, astronomers, naval officers, and others who pursued the long "quest for longitude" to ultimate success. John Harrison’s work in developing extremely advanced marine timekeepers, which was vital to finally solving the problem of longitude, took place against a backdrop of almost unprecedented collaboration and investment. Featured in this complex and fascinating history are the names of Galileo, Isaac Newton, Captain James Cook, and William Bligh of HMS Bounty. -

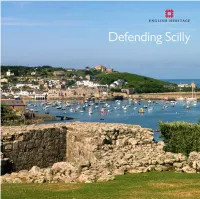

Defending Scilly

Defending Scilly 46992_Text.indd 1 21/1/11 11:56:39 46992_Text.indd 2 21/1/11 11:56:56 Defending Scilly Mark Bowden and Allan Brodie 46992_Text.indd 3 21/1/11 11:57:03 Front cover Published by English Heritage, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ The incomplete Harry’s Walls of the www.english-heritage.org.uk early 1550s overlook the harbour and English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. St Mary’s Pool. In the distance on the © English Heritage 2011 hilltop is Star Castle with the earliest parts of the Garrison Walls on the Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage.NMR hillside below. [DP085489] Maps on pages 95, 97 and the inside back cover are © Crown Copyright and database right 2011. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019088. Inside front cover First published 2011 Woolpack Battery, the most heavily armed battery of the 1740s, commanded ISBN 978 1 84802 043 6 St Mary’s Sound. Its strategic location led to the installation of a Defence Product code 51530 Electric Light position in front of it in c 1900 and a pillbox was inserted into British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data the tip of the battery during the Second A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. World War. All rights reserved [NMR 26571/007] No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without Frontispiece permission in writing from the publisher. -

Rationalizing the Royal Navy in Late Seventeenth-Century England

The Ingenious Mr Dummer: Rationalizing the Royal Navy in Late Seventeenth-Century England Celina Fox In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Royal Navy constituted by far the greatest enterprise in the country. Naval operations in and around the royal dockyards dwarfed civilian industries on account of the capital investment required, running costs incurred and logistical problems encountered. Like most state services, the Navy was not famed as a model of efficiency and innovation. Its day-to-day running was in the hands of the Navy Board, while a small Admiralty Board secretariat dealt with discipline and strategy. The Navy Board was responsible for the industrial organization of the Navy including the six royal dockyards; the design, construction and repair of ships; and the supply of naval stores. In practice its systems more or less worked, although they were heavily dependent on personal relationships and there were endless opportunities for confusion, delay and corruption. The Surveyor of the Navy, invariably a former shipwright and supposedly responsible for the construction and maintenance of all the ships and dockyards, should have acted as a coordinator but rarely did so. The labour force worked mainly on day rates and so had no incentive to be efficient, although a certain esprit de corps could be relied upon in emergencies.1 It was long assumed that an English shipwright of the period learnt his art of building and repairing ships primarily through practical training and experience gained on an apprenticeship, in contrast to French naval architects whose education was grounded on science, above all, mathematics. -

Frindsbury Cricketers Inside This Issue

The Newsletter of the Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre Issue Number 11: August 2008 Frindsbury Cricketers This photograph from the collection of the Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre (FOMA) Chairman, Tessa Towner, will evoke memories of long hot (mythical) Kentish summers. Standing from left, John Walter (Tessa’s grandfather), 4th on left at back his brother Arthur (with peaked cap), known as Tom. Seated with cap, another brother, George Walter, landlord of the Royal Oak pub, Frindsbury. Also in the photo are probably several of the seven Skilton brothers, it was their father Joseph Skilton along with the Rev Jackson, vicar of Frindsbury, who started the Cricket Club in 1885. The date of the photograph has been narrowed down to about 1907 to 1909. Other possible names playing at this time were the Anderson brothers Colin and Donald (both killed in WWI), W.J.Coleman, A.Francis, H.Harpum, M.W.Lewry, A.Lines, A.E.Loach, N.McKechnie, D.Nye, and A.Ring. Inside this issue... We say goodbye to Stephen Dixon, Borough Archivist. After 18 years at the Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre, Stephen left in June for a new post as Archive Service Manager at Essex Record Office, Chelmsford. One of Stephen’s farewell gifts was a framed photograph, taken by FOMA Chairman Tessa Towner, of him on his boat, taken from the Kingswear Castle during the trip on Saturday 31st May 2008 to follow the 100th Medway Barge Match. About The Clock Tower The Clock Tower is the quarterly journal produced and published by the Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre (FOMA).