Indo-US Nuclear Deal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CTC Sentinel Objective

OCTOBER 2011 . VOL 4 . ISSUE 10 COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER AT WEST POINT CTC Sentinel OBJECTIVE . RELEVANT . RIGOROUS Contents Insights from Bin Ladin’s FEATURE ARTICLE 1 Insights from Bin Ladin’s Audiocassette Audiocassette Library in Library in Kandahar By Flagg Miller Kandahar REPORTS By Flagg Miller 5 India’s Approach to Counterinsurgency and the Naxalite Problem By Sameer Lalwani 9 Evaluating Pakistan’s Offensives in Swat and FATA By Daud Khattak 12 The Enduring Appeal of Al-`Awlaqi’s “Constants on the Path of Jihad” By J.M. Berger 15 The Decline of Jihadist Activity in the United Kingdom By James Brandon 17 Understanding the Role of Tribes in Yemen By Charles Schmitz 22 Al-Shabab’s Setbacks in Somalia By Christopher Anzalone 25 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 28 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts s the world waits for the After the tapes were reviewed by U.S. declassification of documents intelligence agencies shortly after their from Usama bin Ladin’s acquisition, the collection was sold to the Abbottabad residence in Williams College Afghan Media Project APakistan, an earlier archive shedding run by American anthropologist David valuable light on al-Qa`ida’s formation Edwards. This author began cataloguing under Bin Ladin is slowly being and archiving the collection in 2003, as released. Acquired by the Cable News soon as the tapes arrived at the college, Network in early 2002 from Bin Ladin’s and is currently writing a book about the About the CTC Sentinel Kandahar compound, more than 1,500 figuration of Bin Ladin’s leadership and The Combating Terrorism Center is an audiocassettes are being made available al-Qa`ida through the archive. -

Pakistan Response Towards Terrorism: a Case Study of Musharraf Regime

PAKISTAN RESPONSE TOWARDS TERRORISM: A CASE STUDY OF MUSHARRAF REGIME By: SHABANA FAYYAZ A thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham May 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The ranging course of terrorism banishing peace and security prospects of today’s Pakistan is seen as a domestic effluent of its own flawed policies, bad governance, and lack of social justice and rule of law in society and widening gulf of trust between the rulers and the ruled. The study focused on policies and performance of the Musharraf government since assuming the mantle of front ranking ally of the United States in its so called ‘war on terror’. The causes of reversal of pre nine-eleven position on Afghanistan and support of its Taliban’s rulers are examined in the light of the geo-strategic compulsions of that crucial time and the structural weakness of military rule that needed external props for legitimacy. The flaws of the response to the terrorist challenges are traced to its total dependence on the hard option to the total neglect of the human factor from which the thesis develops its argument for a holistic approach to security in which the people occupy a central position. -

Batch-13 Candidates Waiting for Exam

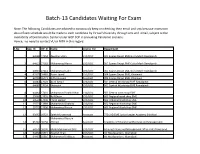

Batch-13 Candidates Waiting For Exam Note: The following Candidates are advised to consciously keep on checking their email and sms because intimation about Exam schedule would be made to each candidate by Virtual University through sms and email, subject to the availability of Examination Center under GOP SOP in prevailing Pandemic scenario. Hence, no need to contact VU or NITB in this regard. S.No App_ID Off_Sr Name Course_For Department 1 64988 17254 Zeeshan Ullah LDC/UDC 301 Spares Depot EME Golra Morh Rawalpindi 2 64923 17262 Muhammad Harris LDC/UDC 301 Spares Depot EME Golra Morh Rawalpindi 3 64945 17261 Muhammad Tahir LDC/UDC 301 Spares Depot EME Golra Morh Rawalpindi 4 62575 16485 Aamir Javed LDC/UDC 304 Spares Depot EME, Khanewal 5 63798 16471 Jaffar Hussain Assistant 304 Spares Depot EME, Khanewal 6 64383 17023 Asim Ismail LDC/UDC 501 Central Workshop EME Rawalpindi 7 64685 17024 Shahrukh LDC/UDC 501 Central Workshop EME Rawalpindi 8 64464 17431 Muhammad Shahid Khan LDC/UDC 502 Central work shop EME 9 29560 17891 Asif Ehsan LDC/UDC 602 Regional work shop EME 10 64540 17036 Imran Qamar LDC/UDC 602 Regional Workshop EME 11 29771 17889 Muhammad Shahroz LDC/UDC 602 Regional Workshop EME 12 29772 17890 Muhammad Faizan LDC/UDC 602 Regional Workshop EME 13 63662 16523 Saleh Muhammad Assistant 770 LAD EME Junior Leader Academy Shinikiari Muhammad Naeem 14 65792 18156 Ahmed Assistant Academy of Educational Planning and Management 15 64378 18100 Malik Muhammad Bilal LDC/UDC Administrative and Management office GHQ Rawalpind 16 64468 16815 -

Afghanistan Factor in the Trilateral Relations of the United States, Pakistan and China (2008-2016)

AFGHANISTAN FACTOR IN THE TRILATERAL RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES, PAKISTAN AND CHINA (2008-2016) By SAIMA PARVEEN Reg. No.12-AU-M.PHIL-P/SCI-F-4 Ph. D (Political Science) SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. JEHANZEB KHALIL Pro-Vice Chancellor Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan Co-Supervisor Prof. Dr. Taj Muharram Khan DEPARTMENT OF POLITCAL SCIENCE FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, ABDUL WALI KHAN UNIVERSITY MARDAN Year 2018 i AFGHANISTAN FACTOR IN THE TRILATERAL RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES, PAKISTAN AND CHINA (2008-2016) By SAIMA PARVEEN Reg. No.12-AU-M.PHIL-P/SCI-F-4 Ph. D (Political Science) Thesis submitted to the Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan in the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph. D in Political Science DEPARTMENT OF POLITCAL SCIENCE FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, ABDUL WALI KHAN UNIVERSITY MARDAN Year 2018 ii Author’s Declaration I, Saima Parveen_hereby state that my Ph D thesis titled, “ Afghanistan Factor in the Trilateral Relations of the United States, Pakistan and China (2008-2016) is my own work and has not been submitted previously by me for taking any degree from this University i.e. ABDUL WALI KHAN UNIVERSITY MARDAN or anywhere else in the country/world. At any time if my statement is found to be incorrect even after my Graduate, the University has the right to withdraw my Ph D degree. Name of Student: Saima Parveen Date: 10 January, 2018 iii Plagiarism Undertaking I solemnly declare that research work presented in the thesis titled “AFGHANISTAN FACTOR IN THE TRILATERAL RELATONS OF THE UNITED STATES, PAKISTAN AND CHINA (2008-2016)” is solely my research work with no significant contribution from any other person. -

A Critical Analysis of Terrorism and Military Operations in Malakand Division (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) After 9/11 Musab Yousufi* Fakhr-Ul-Islam†

Global Social Sciences Review (GSSR) DOI: 10.31703/gssr.2017(II-II).06 p-ISSN 2520-0348, e-ISSN 2616-793X URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gssr.2017(II-II).06 Vol. II, No. II (Fall 2017) Page: 109 - 121 A Critical Analysis of Terrorism and Military Operations in Malakand Division (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) after 9/11 Musab Yousufi* Fakhr-ul-Islam† Abstract The 9/11 was a paradigm shifting event in the international and global politics. On September 11, 2001, two jet planes hit the twin’s tower in United States of America (USA). US official authorities said that it is done by al- Qaeda. This event also changes Pakistan’s internal and foreign policies. The government of United States compel Afghan Taliban government to handover the master mind of 9/11 attack and their leader Osama bin Laden but the talks failed between the both governments. Therefore US government compel the government of Pakistan to give us Military bases and assistance against Afghan Taliban. Pakistan agreed with US as frontline ally of US in war on terror. The majority of Pakistani people were not happy with the decision, therefore, some non-state actors appeared in different part of the country especially in Malakand Division and FATA to support Taliban regime in Afghanistan. In Malakand Division Mulana Sufi Muhammad head of Tehrik Nifaz-e-Shariat-e-Muhammadi started a proper armed campaign for Afghan Taliban Support and sent thousands of people to Afghanistan support Taliban against US and their allied forces. It was a basic reason behind the emergence of terrorism in Malakand division KP but it did not played it role alone to cause terrorism in the region. -

Counterinsurgency in Pakistan

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY institution that helps improve policy and POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY decisionmaking through research and SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY analysis. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND Support RAND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Counterinsurgency in Pakistan Seth G. Jones, C. Christine Fair NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Project supported by a RAND Investment in People and Ideas This monograph results from the RAND Corporation’s Investment in People and Ideas program. -

Rise of Taliban in Waziristan Khan Zeb Burki ∗

Rise of Taliban in Waziristan Khan Zeb Burki ∗ Abstract Waziristan is in the eye of the storm since 2001. After the US invasion of Afghanistan and the overthrow of the Taliban government in 2002, Al-Qaeda and Taliban elements slipped into this region. The existing ground realities like terrain, tradition, administrative system, lack of political power, religious feelings, and socio-economic deprivation prevalent in Waziristan provided favourable and feasible ground for the rise and spread of Talibanization. The Pakistani troops moved into FATA to expel foreigners and check their further infiltration into the Pakistani tribal land. Military actions developed a sense of organization among the local Taliban in order to protect their friends and fight defensive jihad in Waziristan and hence Taliban groups emerged. NUMBER of groups emerged, and some prominent groups are Naik Muhammad Group, Abdullah Mehsud Group, Baitullah Mehsud Taliban Commandos, Mullah Nazir Group, Jalal-Ud- Din Haqani Group, Hafiz Gulbahadur Group. In 2007 a coherent group, Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) came on the horizon. Soon a split occurred in TTP and Turkistan Baitanni Group and Abdullah Shaheed Group headed by Zain Ud Din stood against TTP. These groups remain dominant and have established their own regulation and Sharia in their area of influence. Keywords: Taliban, Waziristan, FATA, Pakistan Introduction The seed of Talibanization in Pakistan lies in General Zia-ul-Haq’s Afghan Policy. The support of Mujahideen and recruiting the Pakistani youth for Jihad in Afghanistan has proven to be a headache for Pakistan. Pakistan provided sanctuary to the Jihadis against the Soviet Union. The later formation of Taliban as an organized force with the help of Pakistani Intelligence Agency the ISI has become now a threat to ∗ Khan Zeb Burki, M. -

Pakistan: Violence Vs. Stability

PAKISTAN: VIOLENCE VS. STABILITY A National Net Assessment Varun Vira and Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy [email protected] Working Draft: 5 May 2011 Please send comments and suggested revisions and additions to [email protected] Vira & Cordesman: Pakistan: Violence & Stability 3/5/11 ii Executive Summary As the events surrounding the death of Osama Bin Laden make all too clear, Pakistan is passing through one of the most dangerous periods of instability in its history. This instability goes far beyond Al Qa‟ida, the Taliban, and the war in Afghanistan. A net assessment of the patterns of violence and stability indicate that Pakistan is approaching a perfect storm of threats, including rising extremism, a failing economy, chronic underdevelopment, and an intensifying war, resulting in unprecedented political, economic and social turmoil. The Burke Chair at CSIS has developed an working draft of a net assessment that addresses each of these threats and areas of internal violence in depth, and does so within in the broader context of the religious, ideological, ethnic, sectarian, and tribal causes at work; along with Pakistan‟s problems in ideology, politics, governance, economics and demographics. The net assessment shows that these broad patterns of violence in Pakistan have serious implications for Pakistan‟s future, for regional stability, and for core US interests. Pakistan remains a central node in global counterterrorism. Osama Bin Laden was killed deep inside Pakistan in an area that raises deep suspicion about what Pakistani intelligence, senior military officers and government officials did and did not know about his presence – and the presence of other major terrorists and extremist like Sheik Mullah Omar and the “Quetta Shura Taliban.” Pakistan pursues its own agenda in Afghanistan in ways that provide the equivalent of cross- border sanctuary for Taliban and Haqqani militants, and that prolong the fighting and cause serious US, ISAF, and Afghan casualties. -

Basic IT Result of Batch-9 Exam Held on Feburary 9 - 10, 2019 Dated: 26-03-19 Note: Failled Or Absentees Need Not Apply Again

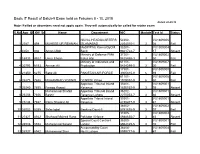

Basic IT Result of Batch-9 Exam held on Feburary 9 - 10, 2019 Dated: 26-03-19 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam S.No App_ID Off_Sr Name Department NIC Module Test Id Status NAVAL HEADQUARTERS, 54302- VU1809006 1 2787 459 MUHEEB UR REHMAN ISLAMABAD 2254010-1 3 36 Fail MoDP/PAC Kamra/DyCM 38201- VU1809004 2 4050 936 Aman Ullah Sectt 9601722-7 6 17 Absent Ministry of Defense PMA 37201- VU1809002 3 16933 4922 Umar Ehsan Kakul Atd 9425498-3 3 50 Fail Ministry of Industries and 61101- VU1809007 4 20793 6193 Ammar Ali Production 5424299-5 3 30 Fail 17301- VU1809000 5 21450 6275 Sabz Ali PAKISTAN AIR FORCE 3005815-9 6 93 Fail 61101- VU1809006 6 24873 7658 MUHAMMAD YOUNIS DCNS(S) Office 1919092-9 6 80 Fail Appellate Tribunal Inland 35401- VU1809001 7 25240 7855 Farooq Rasool Revenue 1826152-9 3 95 Absent Muhammad Shahid Appellate Tribunal Inland 35202- VU1809001 8 25256 7856 Bashir Revenue Lahore 2270053-7 3 86 Absent Appellate Tribnal Inland 33301- VU1809001 9 25234 7857 Rana Shaukat Ali Revenue 4235477-9 3 41 Absent 36302- VU1809002 10 26002 8385 Zafar Iqbal Banking Court-II 8741678-9 3 07 Fail 37405- VU1809003 11 27427 8922 Shahzad Majeed Rana Pakistan Airforce 4988655-7 3 43 Absent Special Court Central-I 35200- VU1809001 12 26906 8934 Muhammad Sarwar Lahore 8962829-5 3 76 Fail Accountability Court 38404- VU1809004 13 26937 8942 Muhammad Sher No.III,Lahore 0999777-5 3 47 Fail Department of Archaeology 61101- VU1809007 14 28075 9309 Inam ul haq qureshi and Museums Islamabad 6145166-3 -

Domestic Barriers to Dismantling the Militant Infrastructure in Pakistan

[PEACEW RKS [ DOMESTIC BARRIERS TO DISMANTLING THE MILITANT INFRASTRUCTURE IN PAKISTAN Stephen Tankel ABOUT THE REPORT This report, sponsored by the U.S. Institute of Peace, examines several underexplored barriers to dismantling Pakistan’s militant infrastructure as a way to inform the understandable, but thus far ineffectual, calls for the coun- try to do more against militancy. It is based on interviews conducted in Pakistan and Washington, DC, as well as on primary and secondary source material collected via field and desk-based research. AUTHOR’S NOTE:This report was drafted before the May 2013 elections and updated soon after. There have been important developments since then, including actions Islamabad and Washington have taken that this report recommends. Specifically, the U.S. announced plans for a resumption of the Strategic Dialogue and the Pakistani government reportedly developed a new counterterrorism strategy. Meanwhile, the situation on the ground in Pakistan continues to evolve. It is almost inevitable that discrete ele- ments of this report of will be overtaken by events. Yet the broader trends and the significant, endogenous obstacles to countering militancy and dismantling the militant infrastruc- ture in Pakistan unfortunately are likely to remain in place for some time. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Stephen Tankel is an assistant professor at American University, nonresident scholar in the South Asia program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and author of Storming the World Stage: The Story of Lashkar- e-Taiba. He has conducted field research on conflicts and militancy in Algeria, Bangladesh, India, Lebanon, Pakistan, and the Balkans. Professor Tankel is a frequent media commentator and adviser to U.S. -

Unclaimed Deposit 2014

Details of the Branch DETAILS OF THE DEPOSITOR/BENEFICIARIYOF THE INSTRUMANT NAME AND ADDRESS OF DEPOSITORS DETAILS OF THE ACCOUNT DETAILS OF THE INSTRUMENT Transaction Federal/P rovincial Last date of Name of Province (FED/PR deposit or in which account Instrume O) Rate Account Type Currency Rate FCS Rate of withdrawal opened/instrume Name of the nt Type In case of applied Amount Eqv.PKR Nature of Deposit ( e.g Current, (USD,EUR,G Type Contract PKR (DD-MON- Code Name nt payable CNIC No/ Passport No Name Address Account Number applicant/ (DD,PO, Instrument NO Date of issue instrumen date Outstandi surrender (LCY,UFZ,FZ) Saving, Fixed BP,AED,JPY, (MTM,FC No (if conversio YYYY) Purchaser FDD,TDR t (DD-MON- ng ed or any other) CHF) SR) any) n , CO) favouring YYYY) the Governm ent 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 PRIX 1 Main Branch Lahore PB Dir.Livestock Quetta MULTAN ROAD, LAHORE. 54500 LCY 02011425198 CD-MISC PHARMACEUTICA TDR 0000000189 06-Jun-04 PKR 500 12-Dec-04 M/S 1 Main Branch Lahore PB MOHAMMAD YUSUF / 1057-01 LCY CD-MISC PKR 34000 22-Mar-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/S BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/SLAHORE LCY 2011423493 CURR PKR 1184.74 10-Apr-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR LCY 2011426340 CURR PKR 156 04-Jan-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING IND HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING INDSTREET NO.3LAHORE LCY 2011431603 CURR PKR 2764.85 30-Dec-04 "WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/SSUNSET LANE 1 Main Branch Lahore PB WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/S LCY 2011455219 CURR PKR 75 19-Mar-04 NO.4,PHASE 11 EXTENTION D.H.A KARACHI " "BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD.FEROZE PUR 1 Main Branch Lahore PB 0301754-7 BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD. -

Indian Soldiers Died in Italy During World War II: 1943-45

Indian Soldiers died in Italy during World War II: 1943-45 ANCONA WAR CEMETERY, Italy Pioneer ABDUL AZIZ , Indian Pioneer Corps. Gurdaspur, Grave Ref. V. B. 1. Sepoy ABDUL JABAR , 10th Baluch Regiment. Hazara, Grave Ref. V. B. 4. Sepoy ABDUL RAHIM , 11th Indian Inf. Bde. Jullundur, Grave Ref. V. D. 6. Rifleman AITA BAHADUR LIMBU , 10th Gurkha Rifles,Dhankuta, Grave Ref. VII. D. 5. Sepoy ALI GAUHAR , 11th Sikh Regiment. Rawalpindi, Grave Ref. V. D. 4. Sepoy ALI MUHAMMAD , 11th Sikh Regiment, Jhelum, Grave Ref. V. B. 6. Cook ALLAH RAKHA , Indian General Service Corps,Rawalpindi, Grave Ref. III. L. 16. Sepoy ALTAF KHAN , Royal Indian Army Service Corps,Alwar, Grave Ref. V. D. 5. Rifleman ANAND KHATTRI, 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles). Grave Ref. VII. B. 7. Sapper ARUMUGAM , 12 Field Coy., Queen Victoria's Own Madras Sappers and Miners. Nanjakalikurichi. Grave Ref. V. B. 2. Rifleman BAL BAHADUR ROKA, 6th Gurkha Rifles. , Grave Ref. VII. B. 5. Rifleman BAL BAHADUR THAPA, 8th Gurkha Rifles.,Tanhu, , Grave Ref. VII. D. 8. Rifleman BHAGTA SHER LIMBU , 7th Gurkha Rifles, Dhankuta, ,Grave Ref. VII. F. 1. Rifleman BHAWAN SING THAPA , 4th Prince of Wales' Own Gurkha Rifles. Gahrung, , Grave Ref. VII. C. 4. Rifleman BHIM BAHADUR CHHETRI , 6th Gurkha Rifles. Gorkha, Grave Ref. VII. C. 5. Rifleman BHUPAL THAPA , 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles). Sallyan, Grave Ref. VII. E. 4. Rifleman BIR BAHADUR SUNWAR , 7th Gurkha Rifles. Ramechhap, Grave Ref. VII. F. 8. Rifleman BIR BAHADUR THAPA, 8th Gurkha Rifles, Palpa, Grave Ref.