Pakistan Response Towards Terrorism: a Case Study of Musharraf Regime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article

Pakistan’s ‘Mainstreaming’ Jihadis Vinay Kaura, Aparna Pande The emergence of the religious right-wing as a formidable political force in Pakistan seems to be an outcome of direct and indirect patron- age of the dominant military over the years. Ever since the creation of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan in 1947, the military establishment has formed a quasi alliance with the conservative religious elements who define a strongly Islamic identity for the country. The alliance has provided Islamism with regional perspectives and encouraged it to exploit the concept of jihad. This trend found its most obvious man- ifestation through the Afghan War. Due to the centrality of Islam in Pakistan’s national identity, secular leaders and groups find it extreme- ly difficult to create a national consensus against groups that describe themselves as soldiers of Islam. Using two case studies, the article ar- gues that political survival of both the military and the radical Islamist parties is based on their tacit understanding. It contends that without de-radicalisation of jihadis, the efforts to ‘mainstream’ them through the electoral process have huge implications for Pakistan’s political sys- tem as well as for prospects of regional peace. Keywords: Islamist, Jihadist, Red Mosque, Taliban, blasphemy, ISI, TLP, Musharraf, Afghanistan Introduction In the last two decades, the relationship between the Islamic faith and political power has emerged as an interesting field of political anal- ysis. Particularly after the revival of the Taliban and the rise of ISIS, Author. Article. Central European Journal of International and Security Studies 14, no. 4: 51–73. -

Theory Talk #35 Barry Buzan on International Society, Securitization

Theory Talks Presents THEORY TALK #35 BARRY BUZAN ON INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY, SECURITIZATION, AND AN ENGLISH SCHOOL MAP OF THE WORLD Theory Talks is an interactive forum for discussion of debates in International Relations with an emphasis of the underlying theoretical issues. By frequently inviting cutting-edge specialists in the field to elucidate their work and to explain current developments both in IR theory and real-world politics, Theory Talks aims to offer both scholars and students a comprehensive view of the field and its most important protagonists. Citation: Schouten, P. (2009) ‘Theory Talk #35: Barry Buzan on International Society, Securitization, and an English School Map of the World’, Theory Talks, http://www.theory- talks.org/2009/12/theory-talk-35.html (19-12-2009) WWW.THEORY‐TALKS.ORG BARRY BUZAN ON INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY, SECURITIZATION, AND AN ENGLISH SCHOOL MAP OF THE WORLD Few thinkers have shown to be as capable as Barry Buzan of continuously impacting the direction of debates in IR theory. From regional security complexes to the English School approach to IR as being about international society, and from hegemony to securitization: Buzan’s name will appear on your reading list. It is therefore an honor for Theory Talks to present this comprehensive Talk with professor Buzan. In this Talk, Buzan – amongst others – discusses theory as thinking-tools, describes the contemporary regionalization of international society, and sketches an English School map of the world. What is, according to you, the biggest challenge / principal debate in current IR? What is your position or answer to this challenge / in this debate? I think the biggest challenge is a dual one, namely, to reconnect international relations with world history and sociology. -

University Law College University of the Punjab, Lahore

1 University Law College University of the Punjab, Lahore. Result of Entry Test of LL.B 03 Years Morning/Afternoon Program Session (2018-2019) (Annual System) held on 12-08-2018* Total Marks: 80 Roll No. Name of Candidate Father's Name Marks 1 Nusrat Mushtaq Mushtaq Ahmed 16 2 Usman Waqas Mohammad Raouf 44 3 Ali Hassan Fayyaz Akhtar 25 4 Muneeb Ahmad Saeed Ahmad 44 5 Sajid Ali Muhammad Aslam 30 6 Muhammad Iqbal Irshad Hussain 23 7 Ameen Babar Abid Hussain Babar Absent 8 Mohsin Jamil Muhammad Jamil 24 9 Syeda Dur e Najaf Bukhari Muhammad Noor ul Ain Bukhari Absent 10 Ihtisham Haider Haji Muhammad Afzal 20 11 Muhammad Nazim Saeed Ahmad 30 12 Muhammad Wajid Abdul Waheed 22 13 Ashiq Hussain Ghulam Hussain 14 14 Abdullah Muzafar Ali 35 15 Naoman Khan Muhammad Ramzan 33 16 Abdullah Masaud Masaud Ahmad Yazdani 30 17 Muhammad Hashim Nadeem Mirza Nadeem Akhtar 39 18 Muhammad Afzaal Muhammad Arshad 13 19 Muhammad Hamza Tahir Nazeer Absent 20 Abdul Ghaffar Muhammad Majeed 19 21 Adeel Jan Ashfaq Muhammad Ashfaq 24 22 Rashid Bashir Bashir Ahmad 35 23 Touseef Akhtar Khursheed Muhammad Akhtar 42 24 Usama Nisar Nisar Ahmad 17 25 Haider Ali Zulfiqar Ali 26 26 Zeeshan Ahmed Sultan Ahmed 28 27 Hafiz Muhammad Asim Muhammad Hanif 32 28 Fatima Maqsood Maqsood Ahmad 12 29 Abdul Waheed Haji Musa Khan 16 30 Simran Shakeel Ahmad 28 31 Muhammad Sami Ullah Muhammad Shoaib 35 32 Muhammad Sajjad Shoukat Ali 27 33 Muhammad Usman Iqbal Allah Ditta Urf M. Iqbal 27 34 Noreen Shahzadi Muhammad Ramzan 19 35 Salman Younas Muhammad Younas Malik 25 36 Zain Ul Abidin Muhammad Aslam 21 37 Muhammad Zaigham Faheem Muhammad Arif 32 38 Shahid Ali Asghar Ali 37 39 Abu Bakar Jameel M. -

Founding of the Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha`At Islam Lahore: Centenary Talk

www.ahmadiyya.org/cont-ahm.htm Founding of the Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha‘at Islam Lahore, March – May 1914 Main points from a Talk by Dr Zahid Aziz at Darus Salaam, Wembley, U.K. on 2nd March 2014 to commemorate the centenary of its establishment 1. Muslim spiritual orders founded by saints existed all over the Indian subcontinent, long before the Ahmadiyya Movement. Usually these were centred around the tomb of the saint. Three flaws had developed in previous movements and sects: a. The headship and control of the movements had passed into the hands of the descendants of the saints. These descendants were capitalising on the repute of the saint to receive homage from the public as well as donations which they used for personal ends. b. These heads of spiritual orders were revered and regarded as holy by their followers because of their descent. They took people into their discipleship and the disciples obeyed them unquestioningly, looking upon them as the gateway to God. c. Leaders of various sects denounced other sects as unbelievers. 2. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad set up a system of running the Ahmadiyya movement after him which avoided these pitfalls. 3. Two and a half years before his death he published his Will in December 1905 and laid down how the movement would be run after him. a. Instead of one spiritual leader who would have all members as his personal disciples, he wrote that after him any forty Ahmadis could choose a venerable person from among them as being fit and suitable to bring newcomers into the Movement by taking bai’at from them in the name of Hazrat Mirza sahib. -

Environmental Security a Conceptual Investigating Study

J Ö N K Ö P I N G I NTERNATIONAL B U S I N E S S S CHOOL JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY Environmental Security A conceptual investigating study Master thesis in Political Science Author: Elin Sporring Jonsson Tutor: Mikael Sandberg Jönköping 2009 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to explore the concept of environmental security. A concept that have made way on to the international arena since the end of the Cold War, and have become of more importance since the 1990’s. The discussion regarding man-made environmental change and its possible impacts on the world is very topical; especially with the Nobel Peace Prize winners in 2007 the Intergovernmental panel on climate change (IPCC) and Al Gore. The concept of environmental security is examined through a conceptual investigating study. The reason for this type of study is due to the complexity of the concept and a hope to find a ‘best’ definition to it. A conceptual investigating study is said to help create order in an existing discussion of a social problem, hence the reason for it in this thesis. The outcome of this thesis is that it is near impossible to find a ‘best’ or one definition to the concept of environmental security and that another method to deal with the concept might have presented another result. Keywords: Environmental Security, Conceptual Investigating Study, Environmental degradation i Sammanfattning Syftet med denna uppsats är att undersöka konceptet environmental security. Detta koncept har gjort sin väg till ett internationellt erkännande sedan Kalla kriget, och har sedan 1990-talet blivit allt mer aktuellt. -

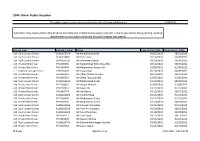

Private Hire and Hackney Carriage Driver Public Register

DPR- Driver Public Register This public register report was correct on the date of being published on 11/08/2021 Data which may display either a blank licence start date and, or blank licence expiry date, this is due to applications being pending, awaiting determination or not issued at the time this public register was created Licence type Licence number Name Licence Start Date Licence Expiry Date L06 Dual Licence Driver DUAL163354 Mr Muhammad Sajid 01/03/2019 28/02/2022 L06 Dual Licence Driver DUAL159861 Mr Zafar Iqbal 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L06 Dual Licence Driver DUAL160322 Mr Shameem Azeem 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160405 Mr Mohammad Rafiq Choudhry 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160438 Mr Mohammed Kurban Ali 01/09/2018 31/08/2021 LL1 Hackney Carriage Driver HCD160418 Mr Liaqat Raja 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160459 Mr Aftab Ahmed Hussain 04/10/2018 30/09/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160522 Mr Zahid Farooq Bhatti 12/09/2018 31/08/2021 L06 Dual Licence Driver DUAL160615 Mr Mohammad Ansar 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160601 Mr Waqar Ahmed 01/09/2018 31/08/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160607 Mr Sajaid Ali 01/11/2018 31/10/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160774 Mr Gul Hayat 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L06 Dual Licence Driver DUAL160623 Mr Syed Ali Raza 01/11/2018 31/10/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160630 Mr Mohammed Sadiq 01/11/2018 31/10/2021 L03 Private Hire Driver PHD160636 Mr Mohammad Hanif 01/10/2018 30/09/2021 L06 Dual Licence Driver DUAL160633 Mr -

Conteporarary Counter Terrorim in Pakistan and Its Efficacy

South Asian Studies A Research Journal of South Asian Studies Vol. 34, No. 1, January – June, 2019, pp. 103 – 123 Conteporarary Counter Terrorim in Pakistan and its Efficacy. Sanwal Hussain Kharl China University of Geosciences, China. Khizar Abbass Bhatti China University of Geosciences, China. Khalid Manzoor Butt Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan. Xiaoqing Xie China University of Geosciences, China. ABSTRACT The study aims to express counter-terrorism situation in Pakistan where terrorism has prevailed in last two decades. There have been more than 100,000 fatalities, the government bears 126 billion US dollars financially, 92 billion US dollars in terms of indirect losses and overall an estimated 10 million people nationally are affected by terrorism. NACTA was formed under National Action Plan to counter terrorism, it was the first step toward concrete anti-terrorism policy. This secondary data based qualitative research highlights efficacy of counter- terrorism policies. The results show the strengths and weaknesses of NACTA framework and its performance. The counter- terrorism strategies minimized security threats demonstrating considerable decrease in numbers of suicide attacks and violent activities. Key Words: Counter-Terrorism, NACTA, SWOT Analysis, Effectiveness Introduction Terrorism has been highly destructive phenomenon for last two decades, especially after 9/11 attacks and Pakistan‟s joining the „War on Terror‟. Approximately 100,000 non-combatant Pakistanis were killed by terrorists in post 9/11 era. According to the government analysis, the direct and indirect economic costs of terrorism up to 2017 have now surpassed $126 billion whereas the other economic loses from the „War on Terror‟ totaled $7543 million between 2016-18 (see Table.1). -

CRSS Annual Security Report 2017

CRSS Annual Security Report 2017 Author: Muhammad Nafees Editor: Zeeshan Salahuddin Table of Contents Table of Contents ___________________________________ 3 Acronyms __________________________________________ 4 Executive Summary __________________________________ 6 Fatalities from Violence in Pakistan _____________________ 8 Victims of Violence in Pakistan________________________ 16 Fatalities of Civilians ................................................................ 16 Fatalities of Security Officials .................................................. 24 Fatalities of Militants, Insurgents and Criminals .................. 26 Nature and Methods of Violence Used _________________ 29 Key militants, criminals, politicians, foreign agents, and others arrested in 2017 ___________________________ 32 Regional Breakdown ________________________________ 33 Balochistan ................................................................................ 33 Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) ......................... 38 Khyber Pukhtunkhwa (KP) ....................................................... 42 Punjab ........................................................................................ 47 Sindh .......................................................................................... 52 Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK), Islamabad, and Gilgit Baltistan (GB) ............................................................................ 59 Sectarian Violence .................................................................... 59 3 © Center -

18 September 2019 PRESS RELEASE 37TH MAJLIS

18 September 2019 PRESS RELEASE 37TH MAJLIS ANSARULLAH IJTEMA UK CONCLUDES WITH ADDRESS BY HEAD OF AHMADIYYA MUSLIM COMMUNITY Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad says the example set by elders should “guide the youth upon the right path.” On 15 September 2019, the World Head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, the Fifth Khalifa (Caliph), His Holiness, Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad delivered the concluding address at the 37th National Ijtema (Annual Gathering) of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Elders Association UK (Majlis Ansarullah). The 3-day event of Majlis Ansarullah, which comprises of male members of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community above the age of 40, was attended by more than 4,600 people from across the UK and was held at the Country Market in Kingsley. During his address His Holiness spoke in detail about the standards of spirituality that the members of Majlis Ansarullah should strive to attain as outlined by the Founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, His Holiness Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the Promised Messiah (peace be upon him). His Holiness highlighted the heavy responsibility that lay upon the members of Majlis Ansarullah to lead by example and said that the young will learn from their elders and follow in their footsteps and thus they should seek to set the best of examples. Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad said: “As the membership of Majlis Ansarullah increases and the organisation progresses, the members of the organisation must self-evaluate to see if they are living up to the expectations laid out by the Promised Messiah (peace be upon him).” -

PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST a Selected Summary of News, Views and Trends from Pakistani Media

February 2017 PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST A Selected Summary of News, Views and Trends from Pakistani Media Prepared by Dr Ashish Shukla & Nazir Ahmed (Research Assistants, Pakistan Project, IDSA) PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST FEBRUARY 2017 A Select Summary of News, Views and Trends from the Pakistani Media Prepared by Dr Ashish Shukla & Nazir Ahmed (Pak-Digest, IDSA) INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES AND ANALYSES 1-Development Enclave, Near USI Delhi Cantonment, New Delhi-110010 Pakistan News Digest, February (1-15) 2017 PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST, FEBRUARY 2017 CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................................... 0 ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................... 2 POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS ............................................................................. 3 NATIONAL POLITICS ....................................................................................... 3 THE PANAMA PAPERS .................................................................................... 7 PROVINCIAL POLITICS .................................................................................... 8 EDITORIALS AND OPINION .......................................................................... 9 FOREIGN POLICY ............................................................................................ 11 EDITORIALS AND OPINION ........................................................................ 12 MILITARY AFFAIRS ............................................................................................. -

10 Pakistan's Nuclear Program

10 PAKISTAN’S NUCLEAR PROGRAM Laying the groundwork for impunity C. Christine Fair Contemporary analysts of Pakistan’s nuclear program speciously assert that Pakistan began acquiring a nuclear weapons capability after the 1971 war with India in which Pakistan was vivisected. In this conventional account, India’s 1974 nuclear tests gave Pakistan further impetus for its program.1 In fact, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Pakistan’s first popularly elected prime minister, ini- tiated the program in the late 1960s despite considerable opposition from Pakistan’s first military dictator General Ayub Khan (henceforth Ayub). Bhutto presciently began arguing for a nuclear weapons program as early as 1964 when China detonated its nuclear devices at Lop Nor and secured its position as a permanent nuclear weapons state under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). Considering China’s test and its defeat of India in the 1962 Sino–Indian war, Bhutto reasoned that India, too, would want to develop a nuclear weapon. He also knew that Pakistan’s civilian nuclear program was far behind India’s, which predated independence in 1947. Notwithstanding these arguments, Ayub opposed acquiring a nuclear weapon both because he believed it would be an expensive misadventure and because he worried that doing so would strain Pakistan’s western alliances, formalized through the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO) and the South-East Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). Ayub also thought Pakistan would be able to buy a nuclear weapon “off the shelf” from one of its allies if India acquired one first.2 With the army opposition obstructing him, Bhutto was unable to make any significant nuclear headway until 1972, when Pakistan’s army lay in disgrace after losing East Pakistan in its 1971 war with India. -

PAKISTAN: REGIONAL RIVALRIES, LOCAL IMPACTS Edited by Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Farzana Shaikh and Gareth Price DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT

DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT PAKISTAN: REGIONAL RIVALRIES, LOCAL IMPACTS Edited by Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Farzana Shaikh and Gareth Price DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT This report is published in collaboration with DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 © Copenhagen 2012, the author and DIIS Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover photo: Protesting Hazara Killings, Press Club, Islamabad, Pakistan, April 2012 © Mahvish Ahmad Layout and maps: Allan Lind Jørgensen, ALJ Design Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-517-2 (pdf ) ISBN 978-87-7605-518-9 (print) Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk Mona Kanwal Sheikh, ph.d., postdoc [email protected] 2 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 Contents Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Pakistan – a stage for regional rivalry 7 The Baloch insurgency and geopolitics 25 Militant groups in FATA and regional rivalries 31 Domestic politics and regional tensions in Pakistan-administered Kashmir 39 Gilgit–Baltistan: sovereignty and territory 47 Punjab and Sindh: expanding frontiers of Jihadism 53 Urban Sindh: region, state and locality 61 3 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 Abstract What connects China to the challenges of separatism in Balochistan? Why is India important when it comes to water shortages in Pakistan? How does jihadism in Punjab and Sindh differ from religious militancy in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA)? Why do Iran and Saudi Arabia matter for the challenges faced by Pakistan in Gilgit–Baltistan? These are some of the questions that are raised and discussed in the analytical contributions of this report.