Lefse, Memory, and a Norwegian-American Identity" (2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 44, Number 4, Winter 2018, Full Issue

Color D Street Water West 312 ONE ecorah, Volume 44 • NUMBER 4 • winter 2018 O TA C TA CH AN I e 52101 owa h O G t MMUNITY F ONEOTA E S E COMMUNITY RV I C E R OO E Q D UE CO S TED - FOOD O www.oneotacoop.com COOPErative P decorah, iowa Slike us on facebookc • followo @oneotacoop ono twitter p RReady,eady, SSet,et, RReeFRESH!FRESH! U.S. Postage U.S. Decorah, IA Decorah, Permit 25 Permit PRST STD PAID ● A better shopping experience with wider aisles, more convenient checkstands. The Oneota Community Co-op (OCC) Board ● A refurbished, cheerful interior that voted at the November meeting to move creates enough rental income and class fee enhances the warm welcome and customer of the remodel project which will occur in two forward with a store remodel/refresh. income to sustain it into the future when we service that we’ve been known for since phases. The first phase will be a replacement Three motions were made and approved: are ready for a larger expansion of our store. 1974. of the store’s refrigeration system. This will 1) Approval of a budget and financing increase energy efficiency, reduce repair Next Steps: and giving the GM the authority to move What led to this decision? costs and decrease product loss from failing ● The GM will finalize the floor plan with forward with the plan. 2) Approval of a future ● Understanding that nationally refrigeration. The second phase is the remodel management and choose contractors for member loan campaign. -

Favorite Foods of the World.Xlsx

FAVORITE FOODS OF THE WORLD - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Third Round Fourth Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Fourth Round Third Round Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Blintzes Duck Confit Papadums Laksa Jambalaya Burrito Cornish Pasty Bulgogi Nori Torta Vegemite Toast Crepes Tagliatelle al Ragù Bouneschlupp Potato Pancakes Hummus Gazpacho Lumpia Philly Cheesesteak Cannelloni Tiramisu Kugel Arepas Cullen Skink Börek Hot and Sour Soup Gelato Bibimbap Black Forest Cake Mousse Croissants Soba Bockwurst Churros Parathas Cream Stew Brie de Meaux Hutspot Crab Rangoon Cupcakes Kartoffelsalat Feta Cheese Kroppkaka PBJ Sandwich Gnocchi Saganaki Mochi Pretzels Chicken Fried Steak Champ Chutney Kofta Pizza Napoletana Étouffée Satay Kebabs Pelmeni Tandoori Chicken Macaroons Yakitori Cheeseburger Penne Pinakbet Dim Sum DIVISION ONE DIVISION TWO Lefse Pad Thai Fastnachts Empanadas Lamb Vindaloo Panzanella Kombu Tourtiere Brownies Falafel Udon Chiles Rellenos Manicotti Borscht Masala Dosa Banh Mi Som Tam BLT Sanwich New England Clam Chowder Smoked Eel Sauerbraten Shumai Moqueca Bubble & Squeak Wontons Cracked Conch Spanakopita Rendang Churrasco Nachos Egg Rolls Knish Pastel de Nata Linzer Torte Chicken Cordon Bleu Chapati Poke Chili con Carne Jollof Rice Ratatouille Hushpuppies Goulash Pernil Weisswurst Gyros Chilli Crab Tonkatsu Speculaas Cookies Fish & Chips Fajitas Gravlax Mozzarella Cheese -

Potato Days Set for Friday and Saturday, August 23 & 24

STREETLIGHT 2019 Barnesville Record-Review 2C Barnesville, Minnesota 56514 Streetlight 2019 Progress Report Potato Days Set For Friday And Saturday, August 23 & 24 Lefse. You either love it or you put sugar on it. Either way, it’s an amazing way to transform a potato. People from all over the country bring their lefse making skills to Barnesville to see if they can be the top dog in the lefse field. they are all winners! The Miss Tator left behind and this amount, plus Tot Contest is open to young girls penalty, is subtracted from the total ages five and six. Each contestant is weight. interviewed and the day of the contest Following the Potato Picking they model a potato sack outfit of contest for adults, the Potato their choice and a party dress. Each Scramble for ages four through contestant is a winner and receives 16 is held in the same potato field. a trophy and is encouraged to ride They are allowed so much time on the float during the Potato Days to pick as many potatoes as they After the kids Potato Scramble, it is time for the adults to dig in the Parade on Saturday at 5:30 p.m. can. They have an added incentive dirt during the Potato Picking Contest. Potato pickers do just that. Although that should be a rousing to picking other than being able to Pick as many potatoes as possible in an allloted amount of time. A good time for many, there is a Teen take the potatoes home with them. -

Neve Shalom Bulletin December 2015

Neve Shalom Bulletin december 2015 NEVE SHALOM FROM THE RABBI By Gerald Zelizer From Our Rabbi….Eric Rosin t has often been observed that peo- customs. And every new ple who are not Jewish will some- relationship and revelation I times leave a social event without gives rise to new possibili- saying goodbye. Jewish people, on the ties. other hand, are notorious for saying Which brings us to the goodbye without leaving. I know that next step in this process of every Shabbat, there comes a moment when I tell my wife, Jen, “Let’s becoming acquainted with start our goodbyes.” This moment may occur anywhere between one another. I may still fifteen minutes and one hour before we actually emerge from the need to be reminded of synagogue and begin our walk home. names for a little longer, but by and large the period of introductions What I’ve learned over the past few months is that saying hello is coming to a close. I am gratified and energized by the realization in the Jewish community isn’t much different. I continue to enjoy that we are transitioning into a period in which our relationships will meeting everyone, but I’m finding out that this process is a marathon grow and flourish through the process of our rolling up our sleeves not a sprint. My first Shabbat in the synagogue the leadership and getting to work together to help the synagogue realize its exhila- offered a wonderful Friday night dinner and Jen and I were treated to rating potential. -

Norwegian Eat Your Way Through Any Holiday with This Cookbook American Story on Page 12-13 Volume 127, #30 • November 4, 2016 Est

the Inside this issue: NORWEGIAN Eat your way through any holiday with this cookbook american story on page 12-13 Volume 127, #30 • November 4, 2016 Est. May 17, 1889 • Formerly Norwegian American Weekly, Western Viking & Nordisk Tidende $3 USD Discovering Helgeland It’s never too late to uncover a new favorite part of Norway PATRICIA BARRY Hopewell Junction, N.Y. “What is your favorite place in Norway?” I world-famous Lofoten Islands, Helgeland— was asked during our trip there in June. Norway’s hidden gem—quietly displays its own I hesitated. Our family has covered lots of unique beauty. territory in Norway. We’ve been to every fylke Helgeland’s partially submerged lowlands (county) and seen more of Norway than most form thousands of skerries that dot the coast- Norwegians, we’ve been told. How could I pick line. Sharp, angular mountains (3,500 ft.) pop WHAT’S INSIDE? one favorite place? up along the coast. Add to this the white sandy And would my answer change? Every trip beaches, glaciers, fjords, inland forests and Nyheter / News 2-3 Du må tørre å ta modige to Norway we seek out new places. On this trip mountains, and the Arctic Circle and you have a « Business og krevende valg. Det finnes 4-5 Helgeland would be our new adventure. combination of features that makes Helgeland a Our entourage included my husband, our unique and stunning part of Norway. ikke noen snarvei. » Opinion 6-7 Sports 8-9 son, our former exchange student, her husband Easily accessible but not as crowded as – Celina Midelfart (our personal tour guide born and raised in Helge- more popular destinations, Helgeland beckons. -

Class Choice Info An

An Introduction to Quilting: Tools, Tips, and Tricks for Class Choice Info the Beginner Take #122 & #222 ‐ Sessions 1 & 2 You may attend up to 5 class sessions. Has quilting always interested you but you don't know where to start? In this class we will discuss the necessary tools required to begin, See this page and following pages for class including cutting mats, rulers, cutters, thread, needles, and sewing machines. We'll also cover tips and tricks to make quilting faster and titles and choices. easier. Keeping it simple, Janelle will demonstrate how to get started Lunch is offered during Session 3 or 4, so on a simple quilting project for the beginner. Instructor: Janelle Braun you'll choose only one class from Sessions 3 and 4, so that you may attend lunch in the Intro to Landscape Design Take #139 & #239‐ Sessions 1 & 2 other. This class will focus on design fundamentals to help you improve and Read class descriptions and select carefully: design your individual landscape from the ground up. Particular Some classes cover two or more sessions and emphasis will be given to: site analysis, exploring how you have used require signing up for all parts consecutively or want to use your landscape or outdoor space, and connecting your (see the rest of the page for all the “two home to your outdoor living space and the surrounding environment. Instructor: David Malda session” classes). Lawn and Garden Equipment Maintenance for the Homeowner Some classes are repeated/offered in more Take #271 & #371 ‐ Sessions 2 & 3 than one session. -

Favorite Foods of the World.Xlsx

FAVORITE FOODS OF THE WORLD - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Third Round Fourth Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Fourth Round Third Round Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Blintzes 53 31 Duck Confit Blintzes 49 20 Duck Confit Papadums 5 23 Laksa Blintzes 23 43 Burrito Jambalaya 32 38 Burrito Jambalaya 36 65 Burrito Cornish Pasty 28 21 Bulgogi Potato Pancakes 43 52 Burrito Nori 35 10 Torta Nori 5 60 Crepes Vegemite Toast 15 49 Crepes Potato Pancakes 61 42 Crepes Tagliatelle al Ragù 18 9 Bouneschlupp Potato Pancakes 81 25 Hummus Potato Pancakes 42 47 Hummus Potato Pancakes 36 49 Burrito Gazpacho 10 22 Lumpia Philly Cheesesteak 44 55 Cannelloni Philly Cheesesteak 49 36 Cannelloni Philly Cheesesteak 39 42 Cannelloni Tiramisu 51 47 Kugel Tiramisu 41 28 Kugel Arepas 8 7 Cullen Skink Gelato 42 34 Mousse Börek 10 26 Hot and Sour Soup Gelato 57 25 Hot and Sour Soup Gelato 49 25 Bibimbap Gelato 46 44 Mousse Black Forest Cake 26 43 Mousse Croissants 28 59 Mousse Croissants 34 16 Soba Cheeseburger Burrito Bockwurst 37 54 Churros Bockwurst 28 45 Churros Parathas 21 6 Cream Stew Crab Rangoon 53 29 Churros Brie de Meaux 20 7 Hutspot Crab Rangoon 57 41 Cupcakes Crab Rangoon 39 50 Cupcakes Crab Rangoon 39 35 Pretzels Kartoffelsalat 28 21 Feta Cheese Kartoffelsalat 13 32 PBJ Sandwich Kroppkaka 22 38 PBJ Sandwich Gnocchi 32 56 Pretzels Gnocchi 43 18 Saganaki Gnocchi 68 53 Pretzels Mochi 14 42 Pretzels -

Potatoes from Garden to Table

FN630 Potatoes from garden to table Julie Garden-Robinson, Ph.D., R.D., L.R.D., Extension food and nutrition specialist Asunta (Susie) Thompson, Ph.D., potato breeder Duane Preston, Extension potato specialist, NDSU and UMN Extension (former) Home-grown potatoes, or those purchased at a farmers market or other venues, are a nutritious part of a healthy diet from early July until the following spring in northern areas. North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota Reviewed February 2019 Cultivar Selection Potato cultivars vary in appearance, maturity, Red-skinned cultivars growing requirements and culinary quality, and are Red-skinned cultivars provide an attractive contrast an excellent source of nutrients, such as potassium. to meat and other vegetables, and tend to have Potatoes are versatile and convenient. You can lower starch content and a waxy texture, making prepare them as baked, boiled, chipped, fried and them most suitable for boiling, roasting, salads, roasted, and use them in soups, salads and stew. soups and stews. They may have a sweet flavor, Choose cultivars that suit your culinary needs particularly after cold storage. Typically, they and those suited to your local growing conditions. are round, although oblong or oval cultivars are Most early cultivars will provide you with “new” becoming common. The majority have white flesh. potatoes, often by the Fourth of July. Those with a Several new cultivars, particularly those from later maturity will require 100 days or more from Europe, have varying shades of yellow flesh. Some emergence to produce a potato crop with acceptable consumers feel these have a “nuttier” flavor. -

Supplementary Material

ICCV ICCV #465 #465 ICCV 2015 Submission #465. CONFIDENTIAL REVIEW COPY. DO NOT DISTRIBUTE. 000 054 001 055 002 056 003 Supplementary Material: 057 004 058 005 Webly Supervised Learning of Convolutional Networks 059 006 060 007 061 008 Anonymous ICCV submission 062 009 063 010 Paper ID 465 064 011 065 012 066 013 067 014 In the supplementary material we include: Somewhat to our surprise, we found the extra clean-up 068 step does not help improving the detection performance. In 015 1. Additional results on PASCAL VOC for ablation anal- 069 fact, the average precision dropped for most of the cate- 016 ysis. 070 017 gories, regardless of whether the bounding box information 071 018 2. Scene classification results. is used or not. We suspect one reason lies in the size of 072 019 the data: after the object localization step, the number of 073 3. Diagnosis results for webly supervised object detec- 020 images was cut in more than a half (∼0.67M compared to 074 tion using [4]. 021 ∼1.5M). Also better algorithms can be devised for cleaning 075 022 4. Lists of objects, scenes and attributes. up web images. 076 023 On the other hand, fine-tuning ImageNet pretrained 077 024 1. Additional Results on PASCAL VOC model to Google images gives slightly better result than 078 training from scratch. However, further investigation is still 025 For ablation analysis, we provide more results on the 079 needed here since IN-GoogleA has seen more images (Im- 026 PASCAL VOC 2007 detection challenge. Please refer to 080 ageNet 1M) than GoogleA. -

The Ultimate Potato Book

The Ultimate Potato Book Hundreds of Ways to Turn America's Favorite Side Dish into a Meal BRUCE WEINSTEIN & MARK SCARBROUGH TO MARIANNE MACY, the sexiest potato eater in Manhattan Contents Introduction 1 A Potato Primer 3 Ingredients and Equipment 11 Potato Recipes, A to Z 17 Potato Recipes Listed by Type of Potato Used 247 Source Guide 250 Index 253 Acknowledgments 273 About the Author Books by Bruce Weinstein Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher Introduction Here's the most radical thing we can tell you: The Ultimate Potato Book is a book of main courses. That may not seem like much--until you think about potatoes. They're side dishes, right? Mashed, roasted, fried, whatever. Sometimes they make a main course debut in a soup; usually they're relegated to the edge of the plate. We've decided to put them front and center. The recipes are alphabetized, mostly without the word ªpotatoº in their titles: Lasagna, in other words, not ªPotato Lasagna.º If you thumb through the book, you'll get the hang of how it works. But we'll admit it right up front: some of our cataloguing is idiosyncrat- ic. Provençal Stew, for example. It's a potato/tomato stew with Pernod. Some main courses naturally include potatoes on the side. Steak Frites, for example. But the potatoes aren't really a ªsideº so much as a co-dish, half the whole, integral to the entree. Although we're passionate about potatoes as main courses, you may still want to make them as traditional sides. -

All About the SES Staff

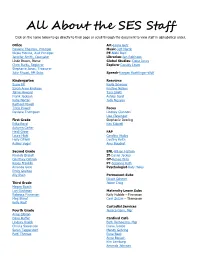

All About the SES Staff Click on the name below to go directly to their page or scroll through the document to view staff in alphabetical order. Office Art-Laura Getz Danielle Chastain, Principal Music-Jeff Martin Nicole Monkul, Asst Principal PE-Nikki Bleill Jennifer Smith, Counselor Librarian-Jen Robinson Linda Brown, Nurse Global Studies- Dana Jones Cheri Burks, Registrar Explore-Cassidy Leum Stephanie Jones, Treasurer Julie Rhoad, AM Subs Speech-Keegan Koehlinger-Wolf Kindergarten Resource Susie Bill Kayla Schnaus Sarah Anne Erickson Kristine Nelson Jaime Howard Tara Smith Frank Jackson Ashley Gard Katie Norton Judy Nguyen Rachael Powell Tricia Powell Focus Danielle Thompson Lindsay Giannoni Lisa Clevenger First Grade Stephanie Dearing Erika Boyd Ken Sidwell Autumn Carter Heidi Greer FAP Laura Hiett Caroline Hudec Holly O'Neill Destiny Keith Ashley Vogel Amy Boudrot Second Grade ENL-Allison Haltom Rhonda Brandt IT-Daniel Jackey Courtney Cohron OT-Renee Wills Kasey Franklin PT-Suzanne Ruth Amanda Gore Psychologist-Katy Haley Emily Greinke Ally Stein Permanent Subs Nicole Scherer Third Grade Jaime Craig Megan Busch Lori Cushman Maternity Leave Subs Rebecca Finnerson Kaily Hubble – Finnerson Meg Strnat Carri Zuzzio – Thompson Kelly Wolf Custodial Services Fourth Grade Jessica Gann, Mgr Anne Gibson Dana Huffer Cardinal Café Lindsey Kraick Beth Verhoestra, Mgr Christa Stevenson Diana Jacobs Sarah Tappendorf Mandy Gehring Patti Thomas Euna Baek Anna Banuch Kim Lemburg Amanda Johnson All About: Euna Baek Favorite Foods Color: Black Animal: -

The History of the Potato in Irish Cuisine and Culture

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Conference papers School of Culinary Arts and Food Technology 2009-01-01 The History of the Potato in Irish Cuisine and Culture Mairtin Mac Con Iomaire Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Pádraic Óg Gallagher Gallagher's Boxty House, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/tfschcafcon Recommended Citation Mac Con Iomaire, M. and P. Gallagher: The History of the Potato in Irish Cuisine and Culture. 'The History of the Potato in Irish Cuisine and Culture' in Friedland, S. (ed) Vegetables: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2008, Devon, Prospect Books This Conference Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Culinary Arts and Food Technology at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Conference papers by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License The History of the Potato in Irish Cuisine and Culture Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire and Pádraic Óg Gallagher Introduction Few plants have been as central to the destiny of the nation as the potato (Solanum tuberosum) has been to Ireland. Ireland was the first European country to accept the potato as a serious food crop. From its introduction in the 16th Century, the potato has held a central place in the Irish diet, and by extension, in the culture of Ireland (Choiseul, Doherty et al.