Altschul2018.Pdf (3.396Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Picrotoxin-Like Channel Blockers of GABAA Receptors

COMMENTARY Picrotoxin-like channel blockers of GABAA receptors Richard W. Olsen* Department of Molecular and Medical Pharmacology, Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1735 icrotoxin (PTX) is the prototypic vous system. Instead of an acetylcholine antagonist of GABAA receptors (ACh) target, the cage convulsants are (GABARs), the primary media- noncompetitive GABAR antagonists act- tors of inhibitory neurotransmis- ing at the PTX site: they inhibit GABAR Psion (rapid and tonic) in the nervous currents and synapses in mammalian neu- system. Picrotoxinin (Fig. 1A), the active rons and inhibit [3H]dihydropicrotoxinin ingredient in this plant convulsant, struc- binding to GABAR sites in brain mem- turally does not resemble GABA, a sim- branes (7, 9). A potent example, t-butyl ple, small amino acid, but it is a polycylic bicyclophosphorothionate, is a major re- compound with no nitrogen atom. The search tool used to assay GABARs by compound somehow prevents ion flow radio-ligand binding (10). through the chloride channel activated by This drug target appears to be the site GABA in the GABAR, a member of the of action of the experimental convulsant cys-loop, ligand-gated ion channel super- pentylenetetrazol (1, 4) and numerous family. Unlike the competitive GABAR polychlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides, antagonist bicuculline, PTX is clearly a including dieldrin, lindane, and fipronil, noncompetitive antagonist (NCA), acting compounds that have been applied in not at the GABA recognition site but per- huge amounts to the environment with haps within the ion channel. Thus PTX major agricultural economic impact (2). ͞ appears to be an excellent example of al- Some of the other potent toxicants insec- losteric modulation, which is extremely ticides were also radiolabeled and used to important in protein function in general characterize receptor action, allowing and especially for GABAR (1). -

Qrno. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 CP 2903 77 100 0 Cfcl3

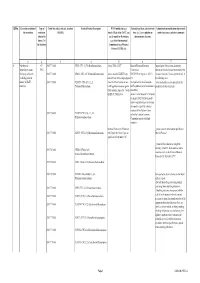

QRNo. General description of Type of Tariff line code(s) affected, based on Detailed Product Description WTO Justification (e.g. National legal basis and entry into Administration, modification of previously the restriction restriction HS(2012) Article XX(g) of the GATT, etc.) force (i.e. Law, regulation or notified measures, and other comments (Symbol in and Grounds for Restriction, administrative decision) Annex 2 of e.g., Other International the Decision) Commitments (e.g. Montreal Protocol, CITES, etc) 12 3 4 5 6 7 1 Prohibition to CP 2903 77 100 0 CFCl3 (CFC-11) Trichlorofluoromethane Article XX(h) GATT Board of Eurasian Economic Import/export of these ozone destroying import/export ozone CP-X Commission substances from/to the customs territory of the destroying substances 2903 77 200 0 CF2Cl2 (CFC-12) Dichlorodifluoromethane Article 46 of the EAEU Treaty DECISION on August 16, 2012 N Eurasian Economic Union is permitted only in (excluding goods in dated 29 may 2014 and paragraphs 134 the following cases: transit) (all EAEU 2903 77 300 0 C2F3Cl3 (CFC-113) 1,1,2- 4 and 37 of the Protocol on non- On legal acts in the field of non- _to be used solely as a raw material for the countries) Trichlorotrifluoroethane tariff regulation measures against tariff regulation (as last amended at 2 production of other chemicals; third countries Annex No. 7 to the June 2016) EAEU of 29 May 2014 Annex 1 to the Decision N 134 dated 16 August 2012 Unit list of goods subject to prohibitions or restrictions on import or export by countries- members of the -

Fluorides in the Environment

Color profile: Disabled Composite 150 lpi at 45 degrees Fluorides in the Environment A4662 - Weinstein - Vouchers - VP10 #K.prn 1 Z:\Customer\CABI\A4642 - Weinstein\A4662 - Weinstein - Vouchers - VP10 #K.vp Monday, November 10, 2003 3:35:50 PM Color profile: Disabled Composite 150 lpi at 45 degrees A4662 - Weinstein - Vouchers - VP10 #K.prn 2 Z:\Customer\CABI\A4642 - Weinstein\A4662 - Weinstein - Vouchers - VP10 #K.vp Monday, November 10, 2003 3:35:50 PM Color profile: Disabled Composite 150 lpi at 45 degrees Fluorides in the Environment Effects on Plants and Animals Professor L.H. Weinstein Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research Tower Road Ithaca NY 14853 USA and Professor A. Davison School of Biology Ridley Building University of Newcastle Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU UK CABI Publishing A4662 - Weinstein - Vouchers - VP10 #K.prn 3 Z:\Customer\CABI\A4642 - Weinstein\A4662 - Weinstein - Vouchers - VP10 #K.vp Monday, November 10, 2003 3:35:51 PM Color profile: Disabled Composite 150 lpi at 45 degrees CABI Publishing is a division of CAB International CABI Publishing CABI Publishing CAB International 875 Massachusetts Avenue Wallingford 7th Floor Oxon OX10 8DE Cambridge, MA 02139 UK USA Tel: +44 (0)1491 832111 Tel: +1 617 395 4056 Fax: +44 (0)1491 833508 Fax: +1 617 354 6875 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.cabi-publishing.org ©L.H. Weinstein and A. Davison 2004. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronically, mechanically, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. -

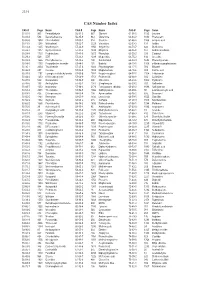

CAS Number Index

2334 CAS Number Index CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name 50-00-0 905 Formaldehyde 56-81-5 967 Glycerol 61-90-5 1135 Leucine 50-02-2 596 Dexamethasone 56-85-9 963 Glutamine 62-44-2 1640 Phenacetin 50-06-6 1654 Phenobarbital 57-00-1 514 Creatine 62-46-4 1166 α-Lipoic acid 50-11-3 1288 Metharbital 57-22-7 2229 Vincristine 62-53-3 131 Aniline 50-12-4 1245 Mephenytoin 57-24-9 1950 Strychnine 62-73-7 626 Dichlorvos 50-23-7 1017 Hydrocortisone 57-27-2 1428 Morphine 63-05-8 127 Androstenedione 50-24-8 1739 Prednisolone 57-41-0 1672 Phenytoin 63-25-2 335 Carbaryl 50-29-3 569 DDT 57-42-1 1239 Meperidine 63-75-2 142 Arecoline 50-33-9 1666 Phenylbutazone 57-43-2 108 Amobarbital 64-04-0 1648 Phenethylamine 50-34-0 1770 Propantheline bromide 57-44-3 191 Barbital 64-13-1 1308 p-Methoxyamphetamine 50-35-1 2054 Thalidomide 57-47-6 1683 Physostigmine 64-17-5 784 Ethanol 50-36-2 497 Cocaine 57-53-4 1249 Meprobamate 64-18-6 909 Formic acid 50-37-3 1197 Lysergic acid diethylamide 57-55-6 1782 Propylene glycol 64-77-7 2104 Tolbutamide 50-44-2 1253 6-Mercaptopurine 57-66-9 1751 Probenecid 64-86-8 506 Colchicine 50-47-5 589 Desipramine 57-74-9 398 Chlordane 65-23-6 1802 Pyridoxine 50-48-6 103 Amitriptyline 57-92-1 1947 Streptomycin 65-29-2 931 Gallamine 50-49-7 1053 Imipramine 57-94-3 2179 Tubocurarine chloride 65-45-2 1888 Salicylamide 50-52-2 2071 Thioridazine 57-96-5 1966 Sulfinpyrazone 65-49-6 98 p-Aminosalicylic acid 50-53-3 426 Chlorpromazine 58-00-4 138 Apomorphine 66-76-2 632 Dicumarol 50-55-5 1841 Reserpine 58-05-9 1136 Leucovorin 66-79-5 -

CHIMPANZEE (Pan Troglodytes ) CARE MANUAL

CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) CARE MANUAL CREATED BY THE AZA Chimpanzee Species Survival Plan® IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE AZA Ape Taxon Advisory Group Chimpanzee (Pan Troglodytes) Care Manual Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Ape TAG 2010. Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Care Manual. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring, MD. Original Completion Date: December 8, 2009 Authors and Significant Contributors: Steve Ross, Ph.D. Lincoln Park Zoo Jennie McNary, Los Angeles Zoo See Appendix F for a full list of contributors and reviewers from the AZA Chimpanzee SSP. Reviewers: Linda Brent, Ph.D., Chimp Haven, Inc. Maria Finnigan, Perth Zoo, ASMP Chimpanzee Coordinator Steve Ross, Ph.D., Lincoln Park Zoo Candice Dorsey, Ph.D., AZA Director, Animal Conservation Debborah Colbert, Ph.D., AZA VP, Animal Conservation Paul Boyle, Ph.D., AZA Sr. VP Conservation and Education See Appendix F for a full list of contributors and reviewers from the AZA Chimpanzee SSP. Chimpanzee Care Manual Project Consultant: Joseph C.E. Barber, Ph.D. AZA Staff Editors: Candice Dorsey, Ph.D., Director, Animal Conservation Cover Photo Credits: Steve Ross Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. The manual assembles basic requirements, best practices, and animal care recommendations to maximize capacity for excellence in animal care and welfare. The manual should be considered a work in progress, since practices continue to evolve through advances in scientific knowledge. The use of information within this manual should be in accordance with all local, state, and federal laws and regulations concerning the care of animals. -

Human Pharmacokinetic Study of Tutin in Honey; a Plant-Derived Neurotoxin ⇑ Barry A

Food and Chemical Toxicology 72 (2014) 234–241 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Food and Chemical Toxicology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodchemtox Human pharmacokinetic study of tutin in honey; a plant-derived neurotoxin ⇑ Barry A. Fields a, , John Reeve b, Andrew Bartholomaeus c,d, Utz Mueller a a Food Standards Australia New Zealand, 55 Blackall St., Barton, ACT 2600, Australia b New Zealand Ministry for Primary Industries, Pastoral House, 25 The Terrace, Wellington, New Zealand c Therapeutics Research Centre, School of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia d School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, Australia article info abstract Article history: Over the last 150 years a number of people in New Zealand have been incapacitated, hospitalised, or died Received 26 March 2014 from eating honey contaminated with tutin, a plant-derived neurotoxin. A feature of the most recent poi- Accepted 16 July 2014 soning incident in 2008 was the large variability in the onset time of clinical signs and symptoms of tox- Available online 30 July 2014 icity (0.5–17 h). To investigate the basis of this variability a pharmacokinetic study was undertaken in which 6 healthy males received a single oral dose of tutin-containing honey giving a tutin dose of Keywords: 1.8 lg/kg body weight. The serum concentration–time curve for all volunteers exhibited two discrete Tutin peaks with the second and higher level occurring at approximately 15 h post-dose. Two subjects reported Neurotoxin mild, transient headache at a time post-dose corresponding to maximum tutin concentrations. There Glycosides Honey were no other signs or symptoms typical of tutin intoxication such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness or sei- Coriaria arborea zures. -

Accepted Version

Article Metabolomics identifies a biomarker revealing in vivo loss of functional ß-cell mass before diabetes onset LI, Lingzi, et al. Abstract Identification of pre-diabetic individuals with decreased functional ß-cell mass is essential for the prevention of diabetes. However, in vivo detection of early asymptomatic ß-cell defect remains unsuccessful. Metabolomics emerged as a powerful tool in providing read-outs of early disease states before clinical manifestation. We aimed at identifying novel plasma biomarkers for loss of functional ß-cell mass in the asymptomatic pre-diabetic stage. Non-targeted and targeted metabolomics were applied on both lean ß-Phb2-/- mice (ß-cell-specific prohibitin-2 knockout) and obese db/db mice (leptin receptor mutant), two distinct mouse models requiring neither chemical nor diet treatments to induce spontaneous decline of functional ß-cell mass promoting progressive diabetes development. Non-targeted metabolomics on ß-Phb2-/- mice identified 48 and 82 significantly affected metabolites in liver and plasma, respectively. Machine learning analysis pointed to deoxyhexose sugars consistently reduced at the asymptomatic pre-diabetic stage, including in db/db mice, showing strong correlation with the gradual loss of ß-cells. [...] Reference LI, Lingzi, et al. Metabolomics identifies a biomarker revealing in vivo loss of functional ß-cell mass before diabetes onset. Diabetes, 2019, vol. 68, no. 12, p. 2272-2286 PMID : 31537525 DOI : 10.2337/db19-0131 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:126176 -

Biology, Medicine, and Surgery of Elephants

BIOLOGY, MEDICINE, AND SURGERY OF ELEPHANTS BIOLOGY, MEDICINE, AND SURGERY OF ELEPHANTS Murray E. Fowler Susan K. Mikota Murray E. Fowler is the editor and author of the bestseller Zoo Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use, or and Wild Animal Medicine, Fifth Edition (Saunders). He has written the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by Medicine and Surgery of South American Camelids; Restraint and Blackwell Publishing, provided that the base fee is paid directly to Handling of Wild and Domestic Animals and Biology; and Medicine the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, and Surgery of South American Wild Animals for Blackwell. He is cur- MA 01923. For those organizations that have been granted a pho- rently Professor Emeritus of Zoological Medicine, University of tocopy license by CCC, a separate system of payments has been California-Davis. For the past four years he has been a part-time arranged. The fee codes for users of the Transactional Reporting employee of Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey’s Circus. Service are ISBN-13: 978-0-8138-0676-1; ISBN-10: 0-8138-0676- 3/2006 $.10. Susan K. Mikota is a co-founder of Elephant Care International and the Director of Veterinary Programs and Research. She is an First edition, 2006 author of Medical Management of the Elephants and numerous arti- cles and book chapters on elephant healthcare and conservation. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data © 2006 Blackwell Publishing Elephant biology, medicine, and surgery / edited by Murray E. All rights reserved Fowler, Susan K. Mikota.—1st ed. -

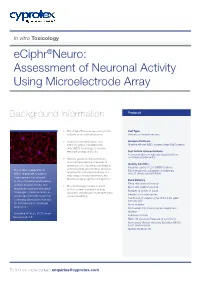

Assessment of Neuronal Activity Using Microelectrode Array

In vitro Toxicology eCiphr®Neuro: Assessment of Neuronal Activity Using Microelectrode Array Background Information Protocol • The eCiphr®Neuro assay uses primary Cell Type cultures of rat cortical neurons. Primary rat cortical neurons • Cyprotex’s neuronal assay uses Analysis Platform high throughput microelectrode Maestro 48-well MEA system (Axion BioSystems) array (MEA) technology to monitor electrophysiological activity. Test Article Concentrations 4 concentrations in triplicate (dependent on customer requirements) • Neurons grown on microelectrode arrays recapitulate many features of Quality Controls neurons in vivo, including spontaneous Negative control: 0.2% DMSO (vehicle) activity (spiking and bursting), plasticity, ‘The unique capabilities of Positive controls: picrotoxin and domoic organisation and responsiveness to a MEAs to provide functional acid (at single concentration) wide range of neurotransmitters and measurements of network pharmacological agonists/antagonists1. activity, including spontaneous Data Delivery Firing rate (spikes/second) activity, evoked activity, and • This technology provides a unique Burst rate (spikes/second) responses to pharmacological in vitro system for preclinical drug Number of spikes in burst challenges, therefore offers an discovery, neurotoxicity assessment and Percent of isolated spikes advantage over other potential disease modelling. Coefficient of variation (CV) of the inter-spike screening approaches that rely intervals (ISI) on biochemical or structural Burst duration endpoints.’ Normalised IQR (inter-quartile range) burst duration 1Robinette BL et al., (2011) Front Interburst interval Neuroeng 4; 1-9 Mean ISI-distance (measure of synchrony) Normalised Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) burst spike number Median ISI/Mean ISI To find out more [email protected] In vitro networks of neurons are spontaneously active and express patterns of electrical activity as part of their normal function2. -

Modeling the Health of Free-Living Illinois Herptiles: an Integrated Approach Incorporating Environmental, Physiologic, Spatiotemporal, and Pathogen Factors

MODELING THE HEALTH OF FREE-LIVING ILLINOIS HERPTILES: AN INTEGRATED APPROACH INCORPORATING ENVIRONMENTAL, PHYSIOLOGIC, SPATIOTEMPORAL, AND PATHOGEN FACTORS BY LAURA ADAMOVICZ DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in VMS-Comparative Biosciences in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2019 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Assistant Professor Matthew Allender, Chair and Research Director Professor CheMyong Jay Ko Associate Professor Megan Mahoney Assistant Professor Rebecca Smith Professor Mark Mitchell, Louisiana State University Sharon Deem, Saint Louis Zoo Institute for Conservation Medicine ABSTRACT Human expansion has contributed to an unprecedented global environmental crisis and significantly impacted the stability of many wildlife populations. The health of wildlife populations influences their ability to recover from a complex array of anthropogenic and natural stressors. Promotion of positive health status may improve conservation outcomes in wild animals. However, wildlife health status is dynamic and determined by a variety of factors. Studying such a complex system requires a comprehensive approach with careful consideration of multiple determinants simultaneously. The purpose of this dissertation is to holistically characterize health in three herptile species of conservation concern in Illinois by combining traditional veterinary health assessments with environmental and spatio-temporal data within a modeling framework. The main objective is to identify the best means of assessing wellness in wild herptiles to inform management strategies which support robust population health. Health was investigated in three species of conservation concern in Illinois: the eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina), the ornate box turtle (Terrapene ornata ornata), and the silvery salamander (Ambystoma platineum) over the course of three years using a combination of physical examination, qPCR pathogen screening, and clinical pathology (box turtles). -

P1029 Tutin Risk Assessment

Supporting document 1 Risk assessment – Proposal P1029 Maximum Level for Tutin in Honey Executive summary Tutin is a plant-derived neurotoxin which is sometimes detected in New Zealand honey. Tutin contamination of honey occurs when bees gather honeydew from an insect that feeds on sap of the shrub Coriaria arborea (“tutu”). Consumption of tutu honeydew honey can result in serious acute adverse health effects. Temporary maximum levels (MLs) for tutin in honey and comb honey of 2 mg/kg and 0.1 mg/kg, respectively, currently exist in the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code (Standard 1.4.1 – Contaminants and Natural Toxicants). For acute neurotoxins, such as tutin, severe symptoms of poisoning (e.g. tonic-clonic convulsions) usually correspond to the time taken to achieve their maximal concentration in serum (typically less than 3-4 hours after ingestion). However, the large variability in the onset time of clinical signs and symptoms of toxicity (0.5 to 17 h with a median of 7.5 h) following tutu honeydew honey ingestion in the 2008 human poisoning incident was difficult to explain. To investigate this variability, which was considered to have potential implications for the existing MLs for tutin, a human pharmacokinetic study was conducted in which 6 healthy adult males each received a single oral dose of tutu honeydew honey. The tutin dose received by the volunteers was equivalent to that received by a high consumer of honey (97.5th percentile) that contains tutin at the ML of 2 mg/kg. The serum tutin concentration profile for all volunteers exhibited two discrete peaks, with the first at 0.5 to 1.5 hours post-dose, and the second and higher serum level occurring at 8 to 16 hours post-dose. -

Managment Guidelines for the Welfare of Zoo Animals 3Rd Edition © British & Irish Association of Zoos & Aquariums 2010

Elephants Loxodonta africana and Elephas maximus Managment Guidelines for the Welfare of Zoo Animals 3rd Edition © British & Irish Association of Zoos & Aquariums 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Management Guidelines for the Welfare of Zoo Animals Elephants Loxodonta africana and Elephas maximus Third edition (2010) Revised by Olivia Walter First published 2002 Published and printed by the British & Irish Association of Zoos & Aquariums, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4RY, United Kingdom ISSN 0963 - 1712 MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES FOR THE WELFARE OF ZOO ANIMALS Elephants 3rd EDITION Incorporating BIAZA’s Policy Statement and Policy Document on the Management of Elephants British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums Management Guidelines for the Welfare of Elephants Document compiled by Olivia Walter, IZVG, for the British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums www.biaza.org.uk 3rd Edition January 2010 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Management Guidelines for the Welfare of Elephants.........................................................................ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ..........................................................................................................III SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................1 1.1 The