Josephus and Vespasian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VESPASIAN. AD 68, Though Not a Particularly Constructive Year For

138 VESPASIAN. AD 68, though not a particularly constructive year for Nero, was to prove fertile ground for senators lion the make". Not that they were to have the time to build anything much other than to carve out a niche for themselves in the annals of history. It was not until the dust finally settled, leaving Vespasian as the last contender standing, that any major building projects were to be initiated under Imperial auspices. However, that does not mean that there is nothing in this period that is of interest to this study. Though Galba, Otho and Vitellius may have had little opportunity to indulge in any significant building activity, and probably given the length and nature of their reigns even less opportunity to consider the possibility of building for their future glory, they did however at the very least use the existing imperial buildings to their own ends, in their own ways continuing what were by now the deeply rooted traditions of the principate. Galba installed himself in what Suetonius terms the palatium (Suet. Galba. 18), which may not necessarily have been the Golden House of Nero, but was part at least of the by now agglomerated sprawl of Imperial residences in Rome that stretched from the summit of the Palatine hill across the valley where now stands the Colosseum to the slopes of the Oppian, and included the Golden House. Vitellius too is said to have used the palatium as his base in Rome (Suet. Vito 16), 139 and is shown by Suetonius to have actively allied himself with Nero's obviously still popular memory (Suet. -

Naval Training Device Center Index of Technical Reports

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 066 013 EM 010 085 AUTHOR Walker, Lemuel E. TITLE Naval Training DeviceCenter Index of Technical Reports. INSTITUTION' Naval Training Device.Center, Orlando, Fla. REPORT NO NAVTRADEV-P-3695 PUB DATE 1 Apr 72 NOTE 65p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Bibliographies; *Government Publications; *Indexes (Locaters); *Military Training; Simulators; *Training Techniques IDENTIFIERS *Naval Training Device Center ABSTRACT Published Naval Training Device Center technical reports and some technical notes (those available through the Defense Documentation Center-DDC) which have resulted from basic research, exploratory development, and advanced development type projects are listed. The reports are indexed by technical note nuhtber, by title, and by contractor code. The index is revised once a year. (Author/JY) ,....,X...?;.;N,..,4,4,40:.W.., e:e ( 0.7 'ta....;.:.: 1 \ 1.4..0.... t,, ti W 1.1 l'.n.,:1;;;,.>,.,:,,,,: ' (- t 4,.,.y.....,..1f... ...1<:<. .,..: ;:x. ,s..:^ '<.,..i.y,W...,,z, :.i -.., .:,..< A ,1 Ke. <,, ;:, P7<<,,".:..:..7. NAVTRADEV P-3695 re I APRIL 1972 ..r;) CD C:) NAVAL TRAINING DEVICE CENTER INDEX OF TECHNICAL REPORTS Basic Research Exploratory Development Advanced Development All titles in this publication are unclassified DoD Distribution Statement U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION Distribution limited to U.S. Government agencies THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO. DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM only; Test and Evaluation; 1 April 1972. Other THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG requests for this document must be referred to INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY Ar;§ the Commanding Officer, Naval Training Device REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU CATION POSITION OR POLICY Center (Code 423) Orlando, Florida 32813. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

10 Bc 5 Bc 1 Ad 5 10 15 20

AD 14 AD 18 4 BC AD 4 Augustus Caiaphas Death of King Emperor Augustus Caesar, the fi rst appointed as Herod the formally adopts his emperor of a Jewish High Great of Judea stepson Tiberius as Rome, dies Priest his successor 10 BC 5 BC 1 AD 5 10 15 20 AD 6 7 BC Jesus a� ends Jesus born in Passover in Bethlehem Jerusalem of Judea as a boy (Luke 2:1-20) (Luke 2:40-52) TIMELINE | PAGE 1 AD 26 Pon� us Pilate begins governorship of Judea 25 30 AD 32 AD 31 Jesus miraculously AD 29 Jesus appoints feeds 5000 John the Bap� st’s and sends his (Ma� hew 14:13-33; ministry begins; Jesus apostles on their AD 30 Mark 6:31-52; is bap� zed and begins fi rst mission Jesus a� ends Luke 9:10-17; John 6) his ministry (Ma� hew 9:35- Passover in (Ma� hew 3:1-17; 11:1; Mark 6:6-13; Jerusalem and Mark 1:2-11; Luke 9:1-10) Luke 3:1-23) cleanses the temple (John 2:13-25) AD 32 AD 30 Jesus a� ends Jesus establishes the Feast of his ministry in Tabernacles in Galilee Jerusalem (Ma� hew 4:12-17; (John 7-9) Mark 1:14-15; Luke 4:14-15) TIMELINE | PAGE 2 AD 43 AD 36 AD 37 AD 40 AD 41 Roman Pon� us Pilate Death of Emperor Caligula Emperor Caligula conquest of governorship of Emperor orders a statue of assassinated and Britain begins Judea ends Tiberius himself be erected in Claudius crowned under Emperor the temple; Jewish the new Emperor Claudius peasants stop this from happening 35 40 AD 37 Paul visits Peter and James in Jerusalem (Acts 9:23-30; Gala� ans 1:18-24) AD 38-43 Missions to the Gen� les begin; church in An� och established AD 33 (Acts 10-11) Jesus crucifi ed -

On the Roman Frontier1

Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers Impact of Empire Roman Empire, c. 200 B.C.–A.D. 476 Edited by Olivier Hekster (Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) Editorial Board Lukas de Blois Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt Elio Lo Cascio Michael Peachin John Rich Christian Witschel VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/imem Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers Edited by Daniëlle Slootjes and Michael Peachin LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016036673 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1572-0500 isbn 978-90-04-32561-6 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-32675-0 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

RUSSIAN ORIENTAL STUDIES This Page Intentionally Left Blank Naumkin-Los.Qxd 10/8/2003 10:33 PM Page Iii

RUSSIAN ORIENTAL STUDIES This page intentionally left blank naumkin-los.qxd 10/8/2003 10:33 PM Page iii RUSSIAN ORIENTAL STUDIES Current Research on Past & Present Asian and African Societies EDITED BY VITALY NAUMKIN BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 naumkin-los.qxd 10/8/2003 10:33 PM Page iv This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Current research on past & present Asian and African societies : Russian Oriental studies / edited by Vitaly Naumkin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-13203-1 (hard back) 1. Asia—Civilization. 2. Africa—Civilization. I. Title: Current research on past and present Asian and African societies. II. Naumkin, Vitalii Viacheslavovich. DS12.C88 2003 950—dc22 2003060233 ISBN 90 04 13203 1 © Copyright 2004 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change printed in the netherland NAUMKIN_f1-v-x 11/18/03 1:27 PM Page v v CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................ vii PART ONE POLITICS AND POWER Monarchy in the Khmer Political Culture .............................. 3 Nadezhda Bektimirova A Shadow of Kleptocracy over Africa (A Theory of Negative Forms of Power Organization) ... -

The First Kirillo-Belozerskij, N° 15 (Kir)

INTRODUCTION 21 the First Makary, N° 6 (Mak), the First Barsov (Bars), the Rumjancev, N° 28 (Rum), the First Kirillo-Belozerskij, N° 15 (Kir). Conjectures suggested by V. M. lstrin in his Paris edition and by Berendts in the notes to his translation have also been introduced into the variant readings. These conjectures and corrections according to other copies are given in the footnotes, and are immediately followed by the surname of the researcher. References to the text of Malalas' chronicle are given according to V. M. Istrin's edition (see bibliography). After the book (indicated in Roman numerals), the page and line of the edition are indicated in Arabic numerals. References to the text of Hamartolus' chronicle are given according to V. M. lstrin's edition: Xronika Georgija Amartola v drevnem slavjanorusskom perevode (The Chronicle of George Hamartolus in the Old Slavorussian Translation), vol. I (text), Petrograd, 1920. The pages and lines of this edition are indicated by numerals. The layout of the text of the History in chapters and parts corresponds to Niese's edition (Berlin, 1894). However, unlike Berendts' translation and Istrin's edition, in which paragraphs are indicated in accordance with Niese's divisions, we do not keep to these divisions, since in the Old Russian translation, the text is at times so divergent from the Greek original that frequently it is not possible to make the paragraphs conform on a line-to-line basis. V JOSEPHUS FLAvrus; HIS LIFE AND WORK; HIS IDEOLOGY; RECEPTION OF HIS WORK BY JEWS AND CHRISTIANS; THE GREEK TEXT AND EARLY TRANSLATIONS. -

California Legislative Pictorial Roster

® California Constitutional/Statewide Officers Governor Lieutenant Governor Attorney General Secretary of State Gavin Newsom (D) Eleni Kounalakis (D) Rob Bonta (D) Shirley Weber (D) State Capitol State Capitol, Room 1114 1300 I Street 1500 11th Street, 6th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 Sacramento, CA 95814 Sacramento, CA 95814 Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 445-2841 (916) 445-8994 (916) 445-9555 (916) 653-6814 Treasurer Controller Insurance Commissioner Superintendent of Public Instruction Fiona Ma (D) Betty T. Yee (D) Ricardo Lara (D) Tony K. Thurmond 915 Capitol Mall, Room 110 300 Capitol Mall, Suite 1850 300 Capitol Mall, Suite 1700 1430 N Street Sacramento, CA 95814 Sacramento, CA 95814 Sacramento, CA 95814 Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 653-2995 (916) 445-2636 (916) 492-3500 (916) 319-0800 Board of Equalization — District 1 Board of Equalization — District 2 Board of Equalization — District 3 Board of Equalization — District 4 Ted Gaines (R) Malia Cohen (D) Tony Vazquez (D) Mike Schaefer (D) 500 Capitol Mall, Suite 1750 1201 K Street, Suite 710 450 N Street, MIC: 72 400 Capitol Mall, Suite 2580 Sacramento, CA 95814 Sacramento, CA 95814 Sacramento, CA 95814 Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 445-2181 (916) 445-4081 (916) 445-4154 (916) 323-9794 ® LEGISLATIVE PICTORIAL ROSTER — 2021-2022 California State Senators Ben Allen (D), SD 26 — Part of Bob J. Archuleta (D), SD 32 Toni Atkins (D), SD 39 — Part Pat Bates (R), SD 36 — Part of Josh Becker (D), SD 13 — Part Los Angeles. (916) 651-4026. —Part of Los Angeles. of San Diego. (916) 651-4039. Orange and San Diego. -

A Week in the Fall of Jerusalem

W ITHERINGTON A Week in the Fall of Jerusalem BEN WITHERINGTON III ivpress.com Taken from A Week in the Fall of Jerusalem by Ben Witherington III. Copyright © 2017 by Ben Witherington III. Published by InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. www.ivpress.com 1 Where There’s Smoke Joanna awoke suddenly to the sound of a shofar blowing, its long, piercing call cleaving the cool morning air. It was barely cockcrow. The sun had not yet penetrated the cracks of the window less house. Rousing herself, she sat up on her improvised couch. The acrid smell of smoke snapped her out of drowsiness. It was not the smell of wood or sacrifice—perhaps tar or pitch? Sh ofar A shofar is a trumpet-like instrument made by hollowing out a horn, usually a ram’s horn. The horns vary in shape and size depending on the age and size of the animal from which they were taken. Typically used at Jewish festivals such as Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement) or Passover, it can also be used in synagogue services. This horn is first mentioned in the Bible in connection with God’s appearance at Mount Sinai (Ex 19:16). A shofar could also be used to signal the beginning of a battle (Josh 6:4; Judg 3:27; 7:16; 1 Sam 8:3). The sound of the shofar was distinguishable from the trumpet, and this is significant in our story, as the Romans used trumpets, not shofars, to give military signals. 8 A Week in the Fall of Jerusalem Fear rose in her chest in a familiar way, and brought back a time in her life when it had been her constant companion. -

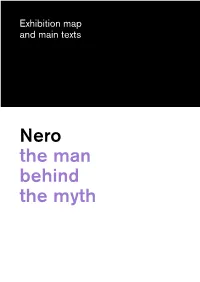

Nero the Man Behind the Myth About This Guide

Exhibition map and main texts Nero the man behind the myth About this guide This guide gives you an overview of the exhibition’s layout and main texts. An online large print guide containing the entire text is also available. Passion and discord Power and succession Fire From republic The new to empire Apollo Spectacle and splendour War and diplomacy Crisis and death A young ruler exit entrance Your visit will take about one hour. 2 Nero the man behind the myth Nero is one of the most infamous Roman emperors. Does he deserve his reputation for cruelty and excess? 3 Introduction A young ruler Nero was the ffth Roman emperor. He came to power aged sixteen and reigned for almost fourteen years, from AD 54 to 68. Nero had to steer a vast empire through a period of great change. Faced with conficting demands and expectations, he adopted policies that appealed to the people, but alienated many members of the elite. Ultimately, his reign came to a premature and tragic close, but this outcome was not predetermined. Nero’s memory was contested. In the end, the judgements of elite authors like Tacitus, Suetonius and Cassius Dio prevailed. In light of new research, now is the time to re-evaluate their stories. 4 From republic to empire From republic to empire Nero was the fnal ruler of Rome’s frst dynasty, the Julio-Claudians, which comprised members of two interrelated families, the Iulii and the Claudii. Some eighty years earlier, Nero’s ancestor Augustus had emerged victorious from decades of civil war. -

Josephus: the Historian and His Society (2Nd Ed.)

JOSEPHUS Remercie humblement aussi ton Créateur Que t'a donné Iosephe, un si fidèle auteur, Certes qui tousiours semble avoir de Dieu guidée La plume, en escrivant tous les faits de Iudée: Car bien qu'il ait suyui le Grec langage orné, Tant s'en faut qu'il se soit à leurs moeurs adonné, Que plutost au vray but de l'histoire il regarde Qu'il ne fait pas au fard d'une langue mignarde. Pierre Tredehan, au peuple françois, 1558. JOSEPHUS The Historian and His Society Tessa Rajak DUCKWORTH This impression 2003 Paperback edition published 2002 First published in 1983 by Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd. 61 Frith Street, London W1D 3JL Tel: 020 7434 4242 Fax: 020 7434 4420 [email protected] www.ducknet.co.uk © 1983, 2002 by Tessa Rajak All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 7156 3170 5 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Bookcraft (Bath) Ltd, Midsomer Norton, Avon Contents Preface to the First Edition vi Preface to the Second Edition vii Introduction to the Second Edition ix Abbreviations xvi Table of events xvii Map: the Palestine of Josephus xviii Introduction 1 1. Family, Education and Formation 11 2. The Greek Language in Josephus'Jerusalem 46 3. Josephus' Account of the Breakdown of Consensus 65 4. Josephus' Interpretation of the Jewish Revolt 78 5. -

First Jewish Revolt

THE FIRST JEWISH REVOlt Throughout much of the first Christian century a had long been a breeding ground for voices of insurrection combination of Hellenistic secularism, Roman politics, and and resistance movements. Even among those who had Jewish ideology created a strange alchemy in Palestinian attempted to avoid confrontation with Rome, increasingly culture and society. The Roman procurators were sometimes bold and bitterly resentful sounds could be heard concerning cruel and defiant, sometimes corrupt or contemptuous of Rome’s tyrannical imperialism.630 Then there was the Jewish Jewish religious practices, and always eager to impose an nationalist sect known as the Zealots that was fervently and excessive tax burden. Jewish sectarianism, in response, absolutely committed to the creation of an independent Jewish state at any cost. (Josephus referred to this as a “fourth philosophy,” in contrast to the three longstanding The lofty and isolated mesa of Masada is crowned with architecture from the time of philosophical groups of Pharisees, Sadducees, and Herod the Great. A 300-foot elevated siege ramp built by the Romans is visible on its Essenes.)631 Suspicions fanned mutual animosities, and covert west side (right side of the picture), in order to employ siege machines and battering intrigue often gave way to open hostility. An atmosphere had rams to capture the city, thus ending the First Jewish Revolt. been created in Judea in which revolution was imminent. 268 The Moody Atlas of the Bible The First Jewish Revolt map 115 A B A series of altercations occurred in rapid Vespasian from Antioch in Syria succession during the spring and early summer of A A a.d.