The Revival of Lucanian Wheat Festivals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Lasting Differences in Civic Capital: Evidence from a Unique Immigration Event in Italy

Long Lasting Differences in Civic Capital: Evidence from a Unique Immigration Event in Italy. E. Bracco, M. De Paola and C. Green Abstract We examine the persistence of cultural differences focusing on the Arberesh in Italy. The Arberesh are a linguistic and ethnic minority living in the south of Italy. They settled in Italy at the end of the XV century, following the invasion of the Balkans by the Ottoman Empire. Using a large dataset from the Italian parliamentary elections of the lower chamber of the Parliament, taking place from 1946 to 2008, we compare turnout in Arberesh municipalities with turnout in indigenous municipalities located in the same geographical areas. We also use two alternative different indicators of social capital like turnout at referendum and at European Parliament Elections. We find that in Arberesh municipalities turnout and compliance rates are higher compared to indigenous municipalities located in the same area. 1 I. INTRODUCTION A range of evidence now exists that demonstrates the relationship between social capital and a range of important socio-economic outcomes. Using a variety of proxies, social capital has been shown to have predictive power across a range of domains, including economic growth (Helliwell and Putnam, 1995; Knack and Keefer, 1997; Zak and Knack, 2001), trade (Guiso et al., 2004), well- functioning institutions (Knack, 2002), low corruption and crime (Uslaner, 2002; Buonanno et al., 2009) and well functioning financial markets (Guiso et al., 2004a). While this literature demonstrates large and long-lived within and across country differences in values, social and cultural norms rather less is known about the origins of these differences. -

Viaggio in Basilicata (Lucania) Dal 1°Al 12 Febbraio 2021

Viaggio in Basilicata (Lucania) Dal 1°al 12 febbraio 2021 A febbraio usciamo con una nuova proposta di eccezionale valore: la Basilicata. Scopriamo il suo cuore elegantemente rurale, scopriamo siti famosi in tutto il mondo come il parco archeologico di Metaponto oppure il cuore della cultura Arberesh a San Costantino Albanese. Ci perderemo tra i vicoli di Satriano di Lucania e Sant'Angelo Le Fratte ammirando i loro meravigliosi Murales. E poi che dire della città fantasma di Craco e della misticità della Cattedrale "L'incompiuta" di Venosa. Tanti altri angoli di Basilicata ci colpiranno e faranno in modo che ci restino nella memoria a lungo. Prima di arrivare in Basilicata abbiamo però inserito alcune meraviglie di Puglia come Trani, Castel del Monte, Bari Vecchia, Polignano a Mare, Altamura e Gravina di Puglia. 1° giorno: 01 febbraio 2021 Trani Ritrovo dei partecipanti presso l’area di sosta camper di Trani, nel tardo pomeriggio. Pernottamento. 2° giorno: 02 febbraio 2021 Trani – Castel del Monte – Bari km 91 Mattinata dedicata alla visita della stupenda cattedrale, la più alta espressione dello stile romanico pugliese, inserita in uno splendido scenario affacciata direttamente sul mare. Al termine della visita ci spostiamo, con i camper, a Castel del Monte per la visita guidata al castello medievale, uno dei luoghi-simbolo della Puglia. È un antichissimo edificio del XIII secolo costruito dall’Imperatore del Sacro Romano Impero, Federico II di Svevia. Proseguiamo poi per Bari. Arrivo e sistemazione di mezzi all’area camper e pernottamento. 3° giorno: 03 febbraio 2021 Bari – Polignano a Mare km 40 Dedichiamo la mattina alla visita guidata (con transfer a/r in navetta) di Bari Vecchia e delle sue chicche come la Basilica di San Nicola e la Piazza Mercantile. -

Aggiornamento Graduatoria

AGGIORNAMENTO GRADUATORIA APPROVATA CON DETERMINA GIRIGENZIALE 76AG n.557 DEL 05/10/2013 RELATIVA ALLA CONCESSIONE DI CONTRIBUTI PER LA MITIGAZIONE DEL RISCHIO SISMICO DI CUI ALL'ART.2, COMMA 1, LETTERA C DELLA OPCM 4007/2012 E OCDPC n.25/2013 - (24/07/2014) Contributo Istanze Pos Richiedente Cofice fiscale Indirizzo Comune Punti Intervento Max Finanziabili Ammissibile 1 GESUALDI FILIPPO GSLFPP45L26D876J VIA SAN ROCCO GALLICCHIO 3.283,500 Rafforzamento locale € 6.500,00 € 6.500,00 2 Salvatore Teresa SLVTRS47D44L181D Borgo San Donato TITO 3.218,402 Rafforzamento locale € 13.000,00 € 13.000,00 3 DONATO ROSINA DNTRSN36H46C619I VIA G. DI GIURA, 85 CHIAROMONTE 3.134,094 Rafforzamento locale € 8.046,00 € 8.046,00 4 BONADIE ANNA BNDNNA73S59L738F VIA TARTAGLIA, 19 LAVELLO 2.898,600 Rafforzamento locale € 8.000,00 € 8.000,00 5 AMATULLI CAROLINA MTLCLN48L53G037Q VIA MONTEBELLO, 32 OLIVETO LUCANO 2.882,684 Rafforzamento locale € 5.000,00 € 5.000,00 6 Petrone Antonio PTRNTN66A14L326H Via San Martino SATRIANO DI LUCANIA 2.813,647 Miglioramento sismico € 45.000,00 € 45.000,00 7 MAFFEO GIUSEPPINA MFFGPP49D48D876W VIA MADONNA DI VIGGIANO, 13 GALLICCHIO 2.789,902 Rafforzamento locale € 15.300,00 € 15.300,00 8 BIANCULLI ANTONIO BNCNTN55B02H994X VIA MARIO PAGANO, 22 SAN MARTINO D'AGRI 2.736,480 Rafforzamento locale € 5.700,00 € 5.700,00 9 CARMIGNANO ENRICO CRMNRC30L28E976M VIA SAN GIUSEPPE, 3 MARSICO NUOVO 2.684,806 Rafforzamento locale € 8.100,00 € 8.100,00 10 CASALASPRO LUIGI CSLLGU44S02D876R VICO PALADINO GALLICCHIO 2.667,844 Rafforzamento locale € 4.000,00 € 4.000,00 11 PIZZILLI SERGIO MARIO ADRIANO PZZSGM53R14G806O C.SO GARIBALDI, 17 POMARICO 2.666,985 Rafforzamento locale € 5.500,00 € 5.500,00 12 MAGGI ANTONIETTA MGGNNT69L71I917R VICO V GARIBALDI, 4 SPINOSO 2.577,781 Rafforzamento locale € 9.000,00 € 9.000,00 13 PASCARELLI PIETRO PSCPRN21D26H994I VIA FELICE ORSINI,5 SAN MARTINO D'AGRI 2.529,395 Rafforzamento locale € 7.400,00 € 7.400,00 14 FERRARA PIETRO GIUSEPPE FRRPRG62H29D766J VIA M. -

Determinazione N.33/2013

AZIENDA TERRITORIALE PER L’EDILIZIA RESIDENZIALE DI POTENZA Via Manhes, 33 – 85100 – POTENZA – tel. 0971413111 – fax. 0971410493 – www.aterpotenza.it URP – NUMERO VERDE – 800291622 – fax 0971 413201 UNITA’ DI DIREZIONE “DIREZIONE “ DETERMINAZIONE N.33/2013 OGGETTO: BANDO PER LA FORMAZIONE DI ELENCHI DI OPERATORI ECONOMICI.(Art. 31 Regolamento per i lavori, le forniture e i servizi in economia). AGGIORNAMENTO ELENCHI OPERATORI ECONOMICI PER LAVORI, FORNITURE E SERVIZI AL 30.06.2013. L'anno 2013 il giorno 4 del mese di luglio nella sede dell'ATER IL DIRETTORE DELL’AZIENDA 1 PREMESSO: - che con delibera dell’Amministratore Unico n. 31 del 06.05.2008 e’ stato approvato il regolamento per i lavori, le forniture e i servizi in economia che prevede, fra l’altro, all’art.31, la costituzione di appositi elenchi di operatori economici atti agli scopi suddetti; - che con successiva delibera dell’A.U. n.32 del 21.05.2008 è stato approvato il Bando per la formazione dei citati elenchi; - che il Bando prevede, altresì, l’aggiornamento degli elenchi degli operatori, senza ulteriori forme di pubblicità, a cadenza semestrale, in base alle domande che pervengono entro il 30/06 e 31/12 di ciascun anno solare; - che, pertanto, si è proceduto alla formazione degli elenchi in relazione alle istanze ammissibili pervenute entro il 30.06.2013 o comunque inviate entro tale termine e validate dalla data del timbro postale sulla raccomandata a..r.; VISTO il regolamento per i lavori, le forniture e i servizi in economia; RITENUTO necessario dover dare attuazione a quanto previsto all’art.31 del Regolamento approvando gli elenchi aggiornati al 30.06.2013 degli operatori economici per i lavori, i servizi e le forniture allegati alla presente per farne parte integrante e sostanziale; VISTI gli articoli 125 e 253, comma 22 del D.Lgs. -

Back Matter (PDF)

Index Page numbers in italics refer to Figures; page numbers in bold refer to Tables Acarinina spp. 200 Apennines 3, 22-23, 27-29, 36, facies cycles Acquarone Ridge 351 38, 40 concept of 177-179 Ad-Dour-Khalladi massif 167 Alpes-Apnnin: 42 description 179, 181,182, Adra Unit 30, 32, 32, 36 Northern 3-5, 19, 23, 33-34, 183, 184, 185, 186, Adige embayment 248, 254 36, 37, 39-41 187-188 Aeolian Island Arc 350, 351 Post-Pseudoverrucano 4 sedimentological significance aeromagnetic surveys Pseudoverrucano 4 188-189 bottom reduction method see also Helminthoid Flysch factorial correspondence analysis application of results Southern 4, 18, 23, 33, 34, 40, methods 148-152 343-347 278-279 results 152-156 data processing 338-339 Argille Varicolori unit 279 results discussed input data 338 evolution 283-286 156-158 signal analysis 339-343 stratigraphy 280-281 significance for African Domain 120, 121 structure 281-283 palaeogeography A1 Alya-A1 Hatba massif 167 Post-Pseudoverrucano 6-9 157, 158 Alboran Basin 3 Pseudoverrucano 4-6 deformation 166-167, 168, Alboran Domain 87-89, 98, 101, structural setting 289-291 170 102, 110, 114 see also Sant'Arcangelo nappe 147-148, 150, 152, Alboran Ridge 112 Basin 155-160, 162, 162-163, Alboran Sea 217, 218 Variszisch-apenninischen 43 164, 165, 165, 167, 168, A1Hamra 138-139 Anageniti Minute formation 19, 168-173, 175 196, 205 Ali Montagnareale Unit 7, 23-24, 20, 21 stratigraphy 163, 164 24, 26, 36 Apuane Unit 3, 19, 20, 21-22, 23, structure 165 Aliano Group 293 39, 40, 42-43 stratigraphy 48 Aliano synthem Apulian -

Annibale Formica Le Comunità Arbëresh Della Val Sarmento

Annibale Formica Le comunità arbëresh della Val Sarmento1 La valle La Val Sarmento è una vallata di appena 4500 abitanti e di 25 mila ettari di territorio rurale e montano. È una piccola enclave, marginale, del versante nord-orientale del Parco Nazionale del Pollino, dove si concentra un patrimonio unico, irripetibile, inestimabile di natura, di paesaggi, di biodiversità, di storia, di tradizioni, di identità, di cultura. Attraverso rocce dolomitiche, pini loricati, boschi di faggio, cuscini di lava, nuclei abitati, comunità arbëresh, siti archeologici, in poche decine di chilometri si passa da un paesaggio “alpino” ad un paesaggio “mediterraneo”. Dopo gli ultimi decenni di abbandono e di spopolamento, il paesaggio, a scendere da Terranova di Pollino alla confluenza nella Valle dei Sinni, è andato via via caratterizzandosi per la notevole espansione della pianta di ginestra, che ha colonizzato gran parte degli ex-coltivi. Alle pendici del Monte Carnara, sul versante orientale del Sarmento, e della Timpa San Nicola, sul versante occidentale, nei luoghi di “fere, sassi, orride ruine, selve incolte e solitarie grotte”, invocati, nelle sue struggenti liriche, entro le mura del suo castello sotto Monte Coppolo, da Isabella Morra, negli anni del XVI secolo in cui la poetessa di Valsinni consumava la sua tragica esistenza, le comunità arbëresh, profughe dalla Morea, hanno formato i loro insediamenti. I due borghi rurali arbëresh si conservano, quasi intatti, nelle loro case in pietra, nei tetti in coppi, nei camini fumanti, nelle scale e nei ballatoi esterni alle abitazioni, negli intricati vicoletti e negli slarghi popolati dalle “gjtonie“ (il vicinato), dalle anziane donne, alcune delle quali vestono nei loro tradizionali costumi e col capo coperto nei tipici panni rossi. -

The Venice Carnival • Cuneo Stone • Antonio Meucci • America, the Musical • Cremona Salami • Gothic Underground

#53 • February 8th, 2015 IN THIS NUMBER: THE VENICE CARNIVAL • CUNEO STONE • ANTONIO MEUCCI • AMERICA, THE MUSICAL • CREMONA SALAMI • GOTHIC UNDERGROUND... & MUCH MORE INTERVIEW WITH Gianluca DE Novi from Basilicata to Harvard # 53 • FEBRUARy 8TH, 2015 Editorial staff We the Italians is a web portal where everybody Umberto Mucci can promote, be informed and keep in touch with anything regarding Italy happening in the US. It is Giovanni Vagnone also the one and only complete archive of every Alessandra Bitetti noncommercial website regarding Italy in the USA, Manuela Bianchi geographically and thematically tagged. Enrico De Iulis Jennifer Gentile Martin We also have our online magazine, which every 15 William Liani days describes some aspects of Italy the beautiful and some of our excellences. Paola Lovisetti Scamihorn We have several columns: all for free, in English, in Simone Callisto Manca your computer or tablet or smartphone, or printed Francesca Papasergi to be read and shared whenever and wherever you Giovanni Verde want. Anna Stein Ready? Go! Plus, articles written by: www.expo2015.org www.borghitalia.it www.buonenotizie.it www.folclore.it www.italia.it www.livingadamis.com MIPAAF © # 53 • February 8th, 2015 UNIONCAMERE ... and many more. SUBSCRIBE OUR NEWSLETTER http://wetheitalians.com/index.php/newsletter CONTACT US [email protected] 2 | WE THE ITALIANS www.wetheitalians.com # 53 • febrUARy 8TH, 2015 INDEX EDITORIAL #53: ITALIAN LITTLE ITALIES: What’s up with WTI Tagliacozzo, The ancient capital of Marsica By Umberto Mucci By I borghi più belli d’Italia pages 4 pages 36-37 THE INTERVIEW: ITALIAN ART: Gianluca De Novi Gothic underground By Umberto Mucci By Enrico De Iulis pages 5-10 pages 38-40 ITALIAN TRADITIONS: GREAT ITALIANS OF THE PAST: The Venice Carnival Antonio Meucci By folclore.it By Giovanni Verde pages 11-13 pages 41-42 ITALIAN CULTURE AND HISTORY: ITALIAN SPORT: House Museums and Historic Homes Tennis, Ferrari and .. -

Venosa – Chiaromonte – Lauria

UNITA’ OPERATIVA PATOLOGIA CLINICA - ASP Laboratorio Analisi Chimiche, cliniche e microbiologiche SEDI: Venosa – (Sede U.O.C.) Altre Sedi: Chiaromonte - Lauria Presentazione L'Unità Operativa di Patologia Clinica dell’ASP ha sede principale presso il Presidio Ospedaliero di Venosa, cui si aggiungono le articolazioni funzionali con sede presso i Presidi Ospedalieri Distrettuali di Chiaromonte e Lauria. Il compito istituzionale consiste nell'eseguire esami e ricerche di diagnostica di laboratorio su campioni a matrice biologica, per fornire informazioni clinicamente utili, corrette e tempestive finalizzate alla gestione appropriata del paziente-utente, perseguendo l’obiettivo di favorire la cultura della prevenzione; di valutare lo stato di salute, orientando la diagnosi e monitorando la terapia instaurata per la cura delle malattie; di offrire un supporto di consulenza nell'interpretazione dei risultati e di suggerire ulteriori indagini di approfondimento diagnostico. Per questa funzione si avvale di risorse professionali, strutturali e strumentali: difatti impiega una equipe costituita da personale dipendente ben motivato, sotto il profilo umano e professionale, appartenente a diverse discipline sanitarie: Medici, Biologi, Tecnici di Laboratorio bio-medico ed Infermieri, che partecipa ai programmi di Educazione Continua in Medicina (ECM) per l'aggiornamento professionale delle figure sanitarie; utilizza tecnologie di ultima generazione per l'attività analitica e si avvale di strumenti che consentono il miglioramento continuo dei requisiti -

WERESILIENT the PATH TOWARDS INCLUSIVE RESILIENCE The

UNISDR ROLE MODEL FOR INCLUSIVE RESILIENCE AND TERRITORIAL SAFETY 2015 #WERESILIENT COMMUNITY CHAMPION “KNOWLEDGE FOR LIFE” - IDDR2015 THE PATH TOWARDS INCLUSIVE RESILIENCE EU COVENANT OF MAYORS FOR CLIMATE AND The Province of Potenza experience ENERGY COORDINATOR 2016 CITY ALLIANCE BEST PRACTICE “BEYOND SDG11” 2018 K-SAFETY EXPO 2018 Experience Sharing Forum: Making Cities Sustainable and Resilient in Korea Incheon, 16th November 2018 Alessandro Attolico Executive Director, Territorial and Environment Services, Province of Potenza, Italy UNISDR Advocate & SFDRR Local Focal Point, UNISDR “Making Cities Resilient” Campaign [email protected] Area of interest REGION: Basilicata (580.000 inh) 2 Provinces: Potenza and Matera PROVINCE OF POTENZA: - AREA: 6.500 sqkm - POPULATION: 378.000 inh - POP. DENSITY: 60 inh/sqkm - MUNICIPALITIES: 100 - CAPITAL CITY: Potenza (67.000 inh) Alessandro Attolico, Province of Potenza, Italy Experience Sharing Forum: Making Cities Sustainable and Resilient in Korea Incheon, November 16th, 2018 • Area of interest Population (2013) Population 60.000 20.000 30.000 40.000 45.000 50.000 65.000 70.000 25.000 35.000 55.000 10.000 15.000 5.000 0 Potenza Melfi Lavello Rionero in Vulture Lauria Venosa distribution Avigliano Tito Senise Pignola Sant'Arcangelo Picerno Genzano di Lagonegro Muro Lucano Marsicovetere Bella Maratea Palazzo San Latronico Rapolla Marsico Nuovo Francavilla in Sinni Pietragalla Moliterno Brienza Atella Oppido Lucano Ruoti Rotonda Paterno Tolve San Fele Tramutola Viggianello -

Wildlife Agriculture Interactions, Spatial Analysis and Trade-Off Between Environmental Sustainability and Risk of Economic Damage

Wildlife Agriculture Interactions, Spatial Analysis and Trade-Off Between Environmental Sustainability and Risk of Economic Damage Mario Cozzi, Severino Romano, Mauro Viccaro, Carmelina Prete, and Giovanni Persiani Abstract Over the last few years, wildlife damages to the agricultural sector have shown an increasing trend at the global scale. Fragile rural areas are more likely to suffer because marginal lands, which have little potential for profit, are being increasingly abandoned. Moreover, public administrations have difficulties to meet the growing requests for crop damage compensations. There is therefore a need to identify appropriate measures to control this growing trend. The specific aim of this research is to understand this phenomenon and define specific and effective action tools. In particular, the proposed research involves different steps that start from the historic analysis of damages and result in the mapping of risk levels using different tests (ANOVA, PCA and spatial correlation) and spatial models (MCE-OWA). The subsequent possibility to cluster risk results ensures greater effectiveness of public actions. The results obtained and the statistical consistency of applied parameters ensure the strength of the analysis and of cost- effectiveness parameters. 1 Introduction Dealing with problems related to the damages caused by wildlife to the agricultural sector involves environmental and socioeconomic sustainability issues associated with the management of natural resources. If, on one hand, farmers are suffering due to the damages caused to crops, on the other, hunters push towards the growth of wild fauna populations for having greater hunting opportunities. This has led to conflicting interests in many European (Wenum et al. 2003; Calenge et al. -

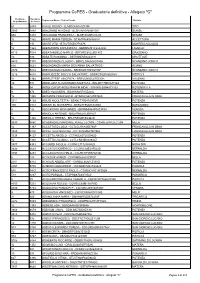

Programma Copes - Graduatoria Definitiva - Allegato "C"

Programma CoPES - Graduatoria definitiva - Allegato "C" Posizione Posizione Cognome e Nome - Codice Fiscale Comune in graduatoria in elenco 61 2839 AAJALI SOUAD - JLASDO65A61Z330F TITO 2080 4893 ABALSAMO ANTONIO - BLSNTN45P28I610W SENISE 694 3478 ABALSAMO FRANCESCA - BLSFNC69R51I610I SENISE 12 1362 ABATE MARIA TERESA - BTAMTR64S49A017I ACCETTURA 8 191 ABATE VITO - BTAVTI56B17F637K MONTESCAGLIOSO 12 1363 ABBAMONTE ANNUNZIATA - BBMNNZ41C65A743J LAVELLO 4119 7014 ABBATANGELO MARCO - BBTMRC60L25E147S GRASSANO 10 530 ABBATE ROSANNA - BBTRNN76B52L418I GROTTOLE 4480 7378 ABBONDANZA CLAUDIO - BBNCLD86A04G786H SCANZANO JONICO 899 3693 ABBONDANZA MARIA GIOVANNA SALVATRICE - ALIANO 2976 5814 ABBONDANZA NUNZIA - BBNNNZ81H49G786F SCANZANO JONICO 1216 4014 ABBRUZZESE ROCCO SALVATORE - BBRRCS82P06B936Y PISTICCI 12 1364 ABBRUZZESE VINCENZA - BBRVCN50C47D513H VALSINNI 10 531 ABDELAZIZ ALI MOHAMED MOSTAFA - BDLMTF79R03Z336Z POTENZA 6 54 ABDULGAFUR ABDULRAHEM NIDAL - BDLNDL60M48Z225J ROTONDELLA 9 474 ABEDI HOUSSEIN - BDAHSN45R15Z224J MATERA 12 1365 ABITANTE FRANCESCO - BTNFNC54C27D766S FRANCAVILLA IN SINNI 1311 4109 ABIUSI NICOLTETTA - BSANLT77B47G975R POTENZA 135 2913 ABKARI EL MUSTAPHA - BKRLST56A01Z330M BARAGIANO 8 192 ABOUKRAIMI MOHAMMED - BKRMMM64P08Z330H VENOSA 4 7 ABRIOLA ANTONIO - BRLNTN62A13G942T POTENZA 12 1366 ABRIOLA TERESA - BRLTRS50B55G942D POTENZA 3039 5886 ACASANDREI MARDARE AUREL FLORIN - CSNRFL68P24Z129N MELFI 12 1367 ACCATTATO LUCIA - CCTLCU58A49D766P FRANCAVILLA IN SINNI 1540 4346 ACCATTATO SANTINA - CCTSTN60M49D766J FRANCAVILLA IN SINNI -

Ministero Della Salute DIREZIONE GENERALE DELLA DIGITALIZZAZIONE, DEL SISTEMA INFORMATIVO SANITARIO E DELLA STATISTICA Ufficio Di Statistica

Ministero della Salute DIREZIONE GENERALE DELLA DIGITALIZZAZIONE, DEL SISTEMA INFORMATIVO SANITARIO E DELLA STATISTICA Ufficio di Statistica Oggetto: Regione Basilicata – Analisi della rete assistenza ambulatoriale nelle aree interne. Le prestazioni specialistiche ambulatoriali erogabili dal Servizio sanitario nazionale costituiscono il livello essenziale di assistenza garantito dal sistema di sanità pubblica in questo regime di erogazione. Si forniscono di seguito i risultati dell’analisi condotta sui dati sui dati relativi alla rete di assistenza ambulatoriale delle aree interne selezionate dalla Regione Basilicata, rilevati per l’anno 2012 attraverso le seguenti fonti informative: - Modelli di rilevazione Decreto Ministro della salute 5 dicembre 2006 STS.11 - Dati anagrafici delle strutture sanitarie; STS.21 - Assistenza specialistica territoriale: attività clinica, di laboratorio, di diagnostica per immagini e di diagnostica strumentale. Le informazioni tratte dalle suddette fonti informative consentono di caratterizzare la rete di offerta di assistenza ambulatoriale dei Comuni oggetto di analisi, con riferimento alle strutture sanitarie presenti nelle aree interne (Fonte STS.11) e ai relativi dati di attività (Fonte STS.21 – quadro F). L’analisi è stata condotta sulla base dei dati trasmessi dalla Regione Basilicata al Ministero della salute, relativamente ai Comuni ricompresi nelle seguenti aree del territorio regionale: ALTO BRADANO: Acerenza, Banzi, Forenza, Genzano di Lucania, Oppido Lucano, Palazzo San Gervasio, San Chirico