Trans* Lives in the Age of Epidemic by Christopher William Roebuck A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engaged Anthropology, Diversity and Dilemmas

Current Anthropology Volume 51 Supplement 2 October 2010 Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas Leslie C. Aiello Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas: Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 2 S201 Setha M. Low and Sally Engle Merry Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas: An Introduction to Supplement 2 S203 Ida Susser The Anthropologist as Social Critic: Working toward a More Engaged Anthropology S227 Barbara Rose Johnston Social Responsibility and the Anthropological Citizen S235 Norma Gonza´lez Advocacy Anthropology and Education: Working through the Binaries S249 Michael Herzfeld Engagement, Gentrification, and the Neoliberal Hijacking of History S259 Signe Howell Norwegian Academic Anthropologists in Public Spaces S269 John L. Jackson Jr. On Ethnographic Sincerity S279 Jonathan Spencer The Perils of Engagement: A Space for Anthropology in the Age of Security? S289 Kamari M. Clarke Toward a Critically Engaged Ethnographic Practice S301 Kamran Asdar Ali Voicing Difference: Gender and Civic Engagement among Karachi’s Poor S313 Alan Smart Tactful Criticism in Hong Kong: The Colonial Past and Engaging with the Present S321 http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/CA Current Anthropology Volume 51, Supplement 2, October 2010 S201 Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 2 by Leslie C. Aiello Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas grew out of a tiative on environmental issues involving 70 international and Wenner-Gren-sponsored workshop titled “The Anthropolo- interdisciplinary scholars who were selected for their common gist as Social Critic: Working toward a More Engaged An- interest and curiosity about the human impact on the earth. thropology” held at the foundation headquarters in New York Among many other Wenner-Gren meetings dealing with City, January 22–25, 2008 (fig. -

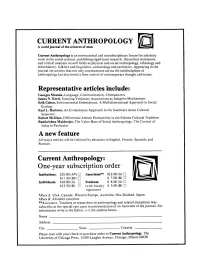

A New Feature Current Anthropology

CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY A world journal of the sciences of man Current Anthropology is an international and interdisciplinary forum for scholarly work in the social sciences, publishing significant research, theoretical statements, and critical analyses in such fields as physical and social anthropology, ethnology and ethnohistory, folklore and linguistics, archaeology and prehistory. Appearing in the journal are articles that not only communicate across the subdisciplines of anthropology but also reveal a firm control of contemporary thought and issues. Representative articles include: Georges Mounin, Language, Communication, Chimpanzees James N. Kerri, Studying Voluntary Associations as Adaptive Mechanisms Erik Cohen, Environmental Orientations: A Multidimensional Approach to Social Ecology Karl L. Hutterer, An Evolutionary Approach to the Southeast Asian Cultural Sequence Robert McGhee, Differential Artistic Productivity in the Eskimo Cuhural Tradition Ramkrisltna Muldierjee, The Value-Base of Social Anthropology: The Context of India in Particular A new feature All major articles will be followed by abstracts in English, French, Spanish, and Russian. Current Anthropology: One-year subscription order Institutions: $25.00 (A*) D Associates* $12.00 (A) D $17.50 (Bf:) D $ 7.00(B) n Individuals: $18.00 (A) D Students: $ 8.00(A) D $12.50(8) D (with faculty $ 5.00(B) D signature) *RateA: USA, Canada, Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Japan tRate B: All other countries **Associates: Teachers or researchers in anthropology and related disciplines may subscribe at the special rate upon recommendation ot an Associate of the journal. For information write to the Editor, c/o the address below. Name Address City . State . Country Please mail with your check or purchase order to Current Anthropology, The University of Chicago Press, 11030 Langley Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60628 SES is a multidisciplinary journal devoted to critical studies in Southwest regional develop ment. -

The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, National Styles, and International Networks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of History and Sociology of Science Departmental Papers (HSS) (HSS) 4-2012 The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, National Styles, and International Networks Susan M. Lindee University of Pennsylvannia, [email protected] Ricardo V. Santos Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hss_papers Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Lindee, S. M., & Santos, R. V. (2012). The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, National Styles, and International Networks. Current Anthropology, 53 (S5), S3-S16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/663335 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hss_papers/22 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, National Styles, and International Networks Abstract We introduce a special issue of Current Anthropology developed from a Wenner-Gren symposium held in Teresópolis, Brazil, in 2010 that was about the past, present, and future of biological anthropology. Our goal was to understand from a comparative international perspective the contexts of genesis and development of physical/biological anthropology around the world. While biological anthropology today can encompass paleoanthropology, primatology, and skeletal biology, our symposium focused on the field's engagement with living human populations. Bringing together scholars in the history of science, science studies, and anthropology, the participants examined the discipline's past in different contexts but also reflected on its contemporary and future conditions. Our contributors explore national histories, collections, and scientific field acticepr with the goal of developing a broader understanding of the discipline's history. -

Current Anthropology Fonds

Current Anthropology fonds Compiled by Erwin Wodarczak (2015) University of British Columbia Archives Table of Contents Fonds Description o Title / Dates of Creation / Physical Description o Administrative History o Custodial History o Scope and Content o Notes Series Descriptions o Sol Tax (Editor) o Rejected Articles o Accepted Publications o Duplicate Files o Editorial Files o CA – General o CA – Accounts o University of Chicago Press Box List Catalogue entry (UBC Library catalogue) Fonds Description Current Anthropology fonds. – 1970-1985. 32.03 m of textual records. Administrative History The journal Current Anthropology is a peer-reviewed academic journal, published by the University of Chicago Press and sponsored by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. Founded in 1959, it is devoted to research that covers the full range of scholarship on human cultures and on the human and other primate species. Current Anthropology publishes research across all sub-disciplines of anthropology, including social, cultural, and physical anthropology, as well as ethnology and ethnohistory, archaeology and prehistory, folklore, and linguistics. Cyril Belshaw, of the UBC Department of Anthropology and Sociology, was editor of Current Anthropology from 1975 to 1985. Custodial History Materials were originally donated to the University Archives by Cyril Belshaw as part of his personal fonds in 1985. With the donation by Belshaw of the rest of his papers in 2015 the fonds was re-organized, and the Current Anthropology records were removed and established as a separate fonds. Scope and Content Fonds consists of editorial files and related materials accumulated by Cyril Belshaw as editor of Current Anthropology. -

An Anthropology of Repatriation: Contemporary Physical Anthropological and Native American Ontologies of Practice

Whittier College Poet Commons Anthropology Faculty Publications & Research 2012 An Anthropology of Repatriation: Contemporary Physical Anthropological and Native American Ontologies of Practice Ann M. Kakaliouras Follow this and additional works at: https://poetcommons.whittier.edu/anth Part of the Anthropology Commons S210 Current Anthropology Volume 53, Supplement 5, April 2012 An Anthropology of Repatriation Contemporary Physical Anthropological and Native American Ontologies of Practice by Ann M. Kakaliouras The policies and politics around the repatriation of ancestral human remains and biological materials to Native North Americans and other indigenous peoples have largely been rooted in attempts to reconcile divergent worldviews about cultural heritage. Even though repatriation has been a legal and practical reality for over 2 decades, controversies between anthropological scientists and repatriation proponents still often dominate professional and scholarly dis- courses over the fate of Native American human remains and associated artifacts. The epistemological gap between Western scientific and indigenous or Native American perspectives—however crucial to bridge in the process of consultation and achieving mutual agreements—is likely to remain. Moreover, although it is a productive legal, sociopolitical, and cultural strategy for many indigenous groups, repatriation as practiced still struggles to funda- mentally transform anthropology’s relationship to indigenous peoples, at least in the United States. In this article I will -

Field-Cv-2018.Pdf

1 CURRICULUM VITAE LES W. FIELD (October 2018) Professor of Anthropology Department of Anthropology University of New Mexico Albuquerque NM 87131 (505) 277-5205; FAX (505) 277-0874 email: [email protected] RESEARCH AREAS AND INTERESTS Nicaragua, Colombia, Ecuador, Indigenous California, Palestine, Greenland Indigenous Identities; Nation-States and Colonial Projects; Nationalist Ideologies and the State; Resources, Agriculture and Development; Social Transformations and Landscapes; Conflict Zones; Licit and Illicit; Collaborative Ethnography, Methods, Epistemologies EDUCATION 1989-90 Post-Doctoral Fellow; Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical, Cali, Colombia 1987 Ph.D., Cultural Anthropology; Duke University 1979 B.S., Anthropology; Johns Hopkins University ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2015-present Chair, Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico 2010-2014 Director, Peace Studies Program, University of New Mexico 2011-2014 Associate Chair, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico 2007- present Full Professor, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico 2007 Acting Director, Latin American and Iberian Institute, University of New Mexico 2005-06 Associate Chair, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico 2000 – 2007 Associate Professor, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico 1994- 2000 Assistant Professor, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico 1991-94 Faculty-In-Residence, Anthropology Department, University of New Hampshire 1991 Visiting Assistant Professor, History Department, San Jose -

Curriculum Vitae

College of Arts and Sciences “Standard Form” for Faculty Vitae Name Department Date Les W. Field Anthropology June 2021 Educational History Ph.D. 1987 Duke University (Durham NC) Cultural Anthropology “I am content with my art: Two groups of artisans in revolutionary Nicaragua,” Carol A. Smith PhD Advisor B.S. 1975 Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore MD) Anthropology Employment History Part I Full Professor, 2008- present, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico Associate Professor, 2000 – 2008, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico Assistant Professor, 1994- 2000 Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico Faculty-In-Residence, 1991-94, Anthropology Department, University of New Hampshire Visiting Assistant Professor, 1991 History Department, San Jose State University Post-Doctoral Fellow, 1989- 1990, Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical, Cali, Colombia Visiting Assistant Professor, 1988 Cultural Anthropology Department, Duke University Employment History Part II Tribal Ethnohistorian, 1991- present, Muwekma Ohlone Tribe (San Jose, CA) Tribal Ethnohistorian, 1994-2000, Esselen Nation of Costanoan Indians (Spreckels CA) Ethnological Consultant, 1998-2000, Federated Coast Miwok (Graton CA) Professional Recognition and Honors Outstanding Teacher of the Year, 2011, OSET-UNM Snead-Wertheim Endowed Lectureship in Anthropology and History, 2008-2009, UNM Departments of Anthropology and History Fulbright IIE Research/Lecturing Fellowship (In Colombia), 2008-10 1 Gunter Starkey Teaching Award, 2000, College -

The Public Value of Anthropology: Engaging Cirtical Social Issues

The Public Value of Anthropology: Engaging Critical Social Issues Through Ethnography Edited by Elisabeth Tauber Dorothy Zinn The Public Value of Anthropology: Engaging Critical Social Issues Through Ethnography Edited by Elisabeth Tauber Dorothy Zinn Design: doc.bz Printing: Digiprint, Bozen/Bolzano © 2015 by Bozen-Bolzano University Press Free University of Bozen-Bolzano All rights reserved 1st edition www.unibz.it/universitypress ISBN 978-88-6046-076-9 E-ISBN 978-88-6046-114-8 This work—excluding the cover and the quotations—is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Table of Contents A Lively and Musing Discipline: The Public Contribution of Anthropology Through Education and Engagement Elisabeth Tauber, Dorothy Zinn .................................................................... 1 Anthropology and Asylum Procedures and Policies in Italy Barbara Sorgoni ......................................................................................... 31 “My dad has fifteen wives and eight ancestors to care for": Conveying Anthropological Knowledge to Children and Adolescents Sabine Klocke-Daffa .................................................................................. 61 Begging—Between Charity and Profession: Reflections on Romanian Roma’s Begging Activities in Italy Cătălina Tesăr ........................................................................................... 83 Crafting Fair Trade Tourism: Gender, Race, and Development in Peru Jane Henrici ............................................................................................ -

Transgender Identities: Towards a Social Analysis of Gender Diversity

Transgender Identities Routledge Research in Gender and Society 1. Economics of the Family and 9. Homosexuality, Law and Family Policies Resistance Edited by Inga Persson and Derek McGhee Christina Jonung 10. Sex Differences in Labor 2. Women’s Work and Wages Markets Edited by Inga Persson and David Neumark Christina Jonung 11. Women, Activism and Social 3. Rethinking Households Change An Atomistic Perspective on European Edited by Maja Mikula Living Arrangements Michel Verdon 12. The Gender of Democracy Citizenship and Gendered Subjectivity 4. Gender, Welfare State and Maro Pantelidou Maloutas the Market Thomas P. Boje and Arnlaug Leira 13. Female Homosexuality in the Middle East 5. Gender, Economy and Culture in Histories and Representations the European Union Samar Habib Simon Duncan and Birgit Pfau Effi nger 14. Global Empowerment of Women 6. Body, Femininity and Nationalism Responses to Globalization and Girls in the German Youth Movement Politicized Religions 1900–1934 Edited by Carolyn M. Elliott Marion E. P. de Ras 15. Child Abuse, Gender and Society 7. Women and the Labour-Market Jackie Turton Self-employment as a Route to Economic Independence 16. Gendering Global Transformations Vani Borooah and Mark Hart Gender, Culture, Race, and Identity Edited by Chima J. Korieh and 8. Victoria’s Daughters Philomina Ihejirika-Okeke The Schooling of Girls in Britain and Ireland 1850–1914 17. Gender, Race and National Identity Jane McDermid and Paula Coonerty Nations of Flesh and Blood Jackie Hogan 18. Intimate Citizenships Gender, Sexualities, Politics Elz·bieta H. Oleksy 19. A Philosophical Investigation of Rape The Making and Unmaking of the Feminine Self Louise du Toit 20. -

Key Issues in Anthropology Sopranzetti

KEY ISSUES IN SOCIAL AND CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY Claudio Sopranzetti 2 credits (MA, 1 year and 2 year programs) Office Hours: Friday 12-14 (in Vienna) Email: [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION: The course examines key theoretical concepts and approaches in past and contemporary anthropology, following two parallel paths. The first focuses on the history of the discipline and explores the development of the French, British and American schools of anthropology. The second and parallel path is thematic and examines key themes and debates in anthropology, namely, on myth and ritual, structure and function, culture and history, meaning and power, gender, capitalism and neoliberalism. The two trajectories start from a questioning of the anthropological canon and some reflections on the project of decolonizing anthropology. During this course, therefore, we will read some parts of this canon but also reflects on its relation to the colonial encounter, its short-comings and potential alternatives. The course is designed to provide students with knowledge of the inventive traditions in anthropology as well as with a critical perspective on the creative process of theory-building. COURSE REQUIREMENTS AND LEARNING OUTCOMES: As this is an introductory course there are no previous requirements. Students are expected to critically engage with the intellectual history of the discipline, address the strength and weakness of different theories and employ the conceptual paradigms in their own research projects (see mid-term paper and final paper). [1] Careful preparation of assigned readings by the date on which they are to be discussed in class. Class discussion will require informed participation on the part of all. -

AN177 Cultural Anthropology

Syllabus Course Number/Title: AN177 Cultural Anthropology Year: Fall 2012 Department: Social Science/Anthropology Credit Hours: 3 Required Texts: CD/Online Text Room #: BMC 712 Introductory Cultural Anthropology: An Interactive Approach Days/Time: MW 10:50-12:05 By Loretta A. Cormier, Sharyn R. Jones 8/22-10/17/12 ISBN Number: 978-1-936306-05-0 Course Placement: Any Instructor: Linda Davis-Stephens, BA, MA, JD Prerequisite: None Office Hours: M-F 9:00 a.m. &M-R@2 p.m. BMC 701 Phone #: 460- 5528 Email [email protected] https://app.onelogin.com/client/apps http://thecollaboratory.wikidot.com/cultural-anthropology-accelerated RATIONALE Cultural Anthropology is suitable for transfer to four-year institutions offering training in the behavioral/social sciences professions. Cultural Anthropology provides the basis for further study of past and present cultures. Students learn by practical experience, involvement and investigation using concepts and theories of anthropology. This disciplined, anthropological experience will complement and enhance students’ academic program of study as well as influence their own lives. COURSE DESCRIPTION Anthropology is the comparative study of past and present human societies and cultures. Cultural Anthropology explores culture as the basis for human experience. Cultural Anthropology is the study of human diversity and universals. Emphasis includes examination of the worldviews of peoples and the areas where they live from a international and interdisciplinary perspective. Students are engaged -

Downloaded From: Ebooks.Adelaide.Edu.Au/D/Descartes/Rene/D44dm/Part2.Html, Sept

A History of Anthropology Eriksen HOA3 00 pre 1 16/04/2013 16:04 Anthropology, Culture and Society Series Editors: Professor Vered Amit, Concordia University and Dr Jon P. Mitchell, University of Sussex Published titles include: Claiming Individuality: Discordant Development: The Aid Effect: The Cultural Politics of Global Capitalism and the Giving and Governing in Distinction Struggle for Connection in International Development EDITED BY VERED AMIT AND Bangladesh EDITED BY DavID MOSSE AND NOEL DYCK KATY GARDNER DavID LEWIS Community, Cosmopolitanism Anthropology, Development Cultivating Development: and the Problem of Human and the Post-Modern An Ethnography of Aid Policy Commonality Challenge and Practice VERED AMIT AND KATY GARDNER AND DavID MOSSE NIGEL RAPPORT DavID LEWIS Contesting Publics Home Spaces, Street Styles: Border Watch: Feminism, Activism, Contesting Power and Identity Cultures of Immigration, Ethnography in a South African City Detention and Control LYNNE PHILLIPS AND SALLY COLE LESLIE J. BANK ALEXANDRA HALL Terror and Violence: In Foreign Fields: Corruption: Imagination and the The Politics and Experiences Anthropological Perspectives Unimaginable of Transnational Sport EDITED BY DIETER HALLER AND EDITED BY ANDREW STRATHERN, Migration CRIS SHORE PAMELA J. STEWART AND THOMAS F. CARTER Anthropology’s World: NEIL L. WHITEHEAD On the Game: Life in a Twenty-First Century Anthropology, Art and Women and Sex Work Discipline Cultural Production SOPHIE DAY ULF HANNERZ MAruškA SvašEK Slave of Allah: Humans and Other Animals Race