Engaged Anthropology, Diversity and Dilemmas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology

An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology By C. Nadia Seremetakis An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology By C. Nadia Seremetakis This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by C. Nadia Seremetakis All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7334-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7334-5 To my students anywhere anytime CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Part I: Exploring Cultures Chapter One ................................................................................................. 4 Redefining Culture and Civilization: The Birth of Anthropology Fieldwork versus Comparative Taxonomic Methodology Diffusion or Independent Invention? Acculturation Culture as Process A Four-Field Discipline Social or Cultural Anthropology? Defining Culture Waiting for the Barbarians Part II: Writing the Other Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 30 Science/Literature Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

Public Anthropology in 2015: <I>Charlie Hebdo</I

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST YEAR IN REVIEW Public Anthropology Public Anthropology in 2015: Charlie Hebdo, Black Lives Matter, Migrants, and More Angelique Haugerud ABSTRACT In this review essay, I focus on how anthropologists have addressed salient public issues such as the European refugee and migrant crisis, the Black Lives Matter movement, and the attack on the Paris office of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. Public anthropology relies on slow ethnography and fast responses to breaking news stories. It is theoretically informed but reaches out to audiences beyond the academy. Drawing on proliferating anthropological contributions to news media and blogs, as well as scholarly articles and books, I explore how anthropologists today counter grand narratives such as the “clash of civilizations”; how they grapple with risky popular misconceptions of culture, difference, and suffering; and how they surface less visible forms of compassion, care, and solidarity that have long sustained our species. The challenges of this era of growing polarization and anti-intellectualism appear to have energized rather than quieted public anthropology. [public anthropology, Charlie Hebdo, Black Lives Matter, migrants, year in review] RESUMEN En este ensayo de revision,´ centro mi atencion´ en como´ los antropologos´ han abordado cuestiones publicas´ relevantes tales como la crisis de migrantes y refugiados en Europa, el movimiento las Vidas Negras Importan, y el ataque a la oficina de Parıs´ del magazine satırico´ Charlie Hebdo. La antropologıa´ publica´ depende de la etnografıa´ lenta y las respuestas rapidas´ a las historias de noticas de ultima´ hora. Es teoricamente´ informada, pero alcanza a llegar a audiencias mas´ alla´ de la academia. -

SM 5 Culture Genuine and Spurious

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eVols at University of Hawaii at Manoa Savage Minds Occasional Papers No. 5 Culture, Genuine and Spurious By Edward Sapir Edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub First edition, 5 November, 2013 Savage Minds Occasional Papers 1. The Superorganic by Alfred Kroeber, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 2. Responses to “The Superorganic”: Texts by Alexander Goldenweiser and Edward Sapir, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 3. The History of the Personality of Anthropology by Alfred Kroeber, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 4. Culture and Ethnology by Robert Lowie, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 5. Culture, Genuine and Spurious by Edward Sapir, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub Copyright information This original work is copyright by Alex Golub, 2013. The author has issued the work under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license. You are free • to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work • to remix - to adapt the work Under the following conditions • attribution - you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author • noncommercial - you may not use this work for commercial purposes • share alike - if you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one This work includes excerpts from Sapir, Edward. 1924. Culture, genuine and spurious. American Journal of Sociology 29 (4): 401-429. This work is in the public domain. -

Why a Public Anthropology? Notes and References

WHY A PUBLIC ANTHROPOLOGY? NOTES AND REFERENCES While the placement of notes and references online is still relatively rare, they are quite easy to examine in a PDF online format. Readers should use find (or control F) with a fragment of the quote to discover the cited reference. In a number of cases, I have added additional material so advanced readers, if they wish, can explore the issue in greater depth. Find can also be used to track down relevant citations, explore a topic of interest, or locate a particular section (e.g. Chapter 2 or 3.4). May I make a request? Since this Notes and References section contains over 1,300 references, it is likely that, despite my best efforts, there are still incomplete references and errors. I would appreciate readers pointing them out to me, especially since I can, in most cases, readily correct them. Thank you. Readers can email me at [email protected]. Quotes from Jim Yong Kim: On Leadership , Washington Post (April 1, 2010, listed as March 31, 2010) http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp- dyn/content/video/2010/03/31/VI2010033100606.html?hpid=smartliving CHAPTER 1 1.1 Bronislaw Malinowski, a prominent early twentieth century anthropologist, famously stated his goal in anthropology was "to grasp the native's point of view, his relation to life, to realize his vision of his world" (1961 [1922]:25) To do this, he lived as a participant-observer for roughly two years – between 1915-1918 – among the Trobriand Islanders of Papua New Guinea (in the South Pacific). Quoting him (1961[1922]:7-8): There is all the difference between a sporadic plunging into the company of natives, and being really in contact with them. -

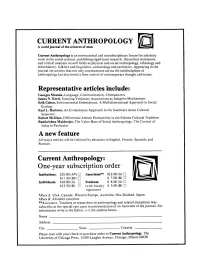

A New Feature Current Anthropology

CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY A world journal of the sciences of man Current Anthropology is an international and interdisciplinary forum for scholarly work in the social sciences, publishing significant research, theoretical statements, and critical analyses in such fields as physical and social anthropology, ethnology and ethnohistory, folklore and linguistics, archaeology and prehistory. Appearing in the journal are articles that not only communicate across the subdisciplines of anthropology but also reveal a firm control of contemporary thought and issues. Representative articles include: Georges Mounin, Language, Communication, Chimpanzees James N. Kerri, Studying Voluntary Associations as Adaptive Mechanisms Erik Cohen, Environmental Orientations: A Multidimensional Approach to Social Ecology Karl L. Hutterer, An Evolutionary Approach to the Southeast Asian Cultural Sequence Robert McGhee, Differential Artistic Productivity in the Eskimo Cuhural Tradition Ramkrisltna Muldierjee, The Value-Base of Social Anthropology: The Context of India in Particular A new feature All major articles will be followed by abstracts in English, French, Spanish, and Russian. Current Anthropology: One-year subscription order Institutions: $25.00 (A*) D Associates* $12.00 (A) D $17.50 (Bf:) D $ 7.00(B) n Individuals: $18.00 (A) D Students: $ 8.00(A) D $12.50(8) D (with faculty $ 5.00(B) D signature) *RateA: USA, Canada, Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Japan tRate B: All other countries **Associates: Teachers or researchers in anthropology and related disciplines may subscribe at the special rate upon recommendation ot an Associate of the journal. For information write to the Editor, c/o the address below. Name Address City . State . Country Please mail with your check or purchase order to Current Anthropology, The University of Chicago Press, 11030 Langley Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60628 SES is a multidisciplinary journal devoted to critical studies in Southwest regional develop ment. -

The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, National Styles, and International Networks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of History and Sociology of Science Departmental Papers (HSS) (HSS) 4-2012 The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, National Styles, and International Networks Susan M. Lindee University of Pennsylvannia, [email protected] Ricardo V. Santos Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hss_papers Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Lindee, S. M., & Santos, R. V. (2012). The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, National Styles, and International Networks. Current Anthropology, 53 (S5), S3-S16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/663335 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hss_papers/22 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, National Styles, and International Networks Abstract We introduce a special issue of Current Anthropology developed from a Wenner-Gren symposium held in Teresópolis, Brazil, in 2010 that was about the past, present, and future of biological anthropology. Our goal was to understand from a comparative international perspective the contexts of genesis and development of physical/biological anthropology around the world. While biological anthropology today can encompass paleoanthropology, primatology, and skeletal biology, our symposium focused on the field's engagement with living human populations. Bringing together scholars in the history of science, science studies, and anthropology, the participants examined the discipline's past in different contexts but also reflected on its contemporary and future conditions. Our contributors explore national histories, collections, and scientific field acticepr with the goal of developing a broader understanding of the discipline's history. -

Trans* Lives in the Age of Epidemic by Christopher William Roebuck A

“Workin’ It:” Trans* Lives in the Age of Epidemic by Christopher William Roebuck A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Lawrence Cohen, Chair Professor Judith Butler Professor Sharon Kaufman Professor Aihwa Ong Spring 2013 Copyright (2013) by Christopher William Roebuck Abstract “Workin’ It”: Trans* Lives in the Age of Epidemic by Christopher William Roebuck Joint Doctor of Philosophy with University of California, San Francisco In Medical Anthropology University of California Professor Lawrence Cohen, Chair Situated in the interstices of anthropology, public health, and critical theory, this dissertation pursues questions of gender, health, transnationality, and governance. It does so through a critical medical anthropological study of trans* lives during what has been referred to as “the second wave of AIDS” in San Francisco. According to public health research and epidemiological studies, urban transgender women are reported to constitute one of most vulnerable populations for HIV infection in the United States. Combining research methods of medical anthropology and urban ethnography, this dissertation explores self-making and world- making practices of trans* individuals during a time, I call “the age of epidemic.” Multi-year ethnographic research was based primarily in San Francisco’s Tenderloin, a low-income, culturally diverse neighborhood that has been referred to as the “epi-center of the AIDS epidemic” in San Francisco. At the same time, it is home and center of social life for many trans* immigrants from Mexico, Central and South American, and South-east Asia, who migrate to the city in hopes of creating vibrant lives. -

CHAPTER 1 Anthropological Perspectives Learning Objectives

CHAPTER 1 Anthropological Perspectives Learning Objectives Chapter Objectives This chapter introduces anthropology as an academic subject and explores its historical development. It discusses various theoretical and contemporary perspectives on fieldwork and ethnography. It also explores how the evolutionary past of primates and early humans is used and understood by contemporary cultural anthropologists. • Learning Objective 1: Understand the definitions of culture and the subdisciplines of anthropology. • Learning Objective 2: Understand the differences between cultural relativity and ethnocentrism. • Learning Objective 3: Understand the significance of the major characteristics, physical and cognitive, of Homo sapiens and how they differ from earlier hominids. • Learning Objective 4: Understand the history of anthropology and the changes in the discipline over the past 150 years. • Learning Objective 5: Understand how the metaphor of the “tapestry” applies to learning about culture. Sample Questions Multiple choice questions Select the one answer that best completes the thought. 1. Anthropology can be best described as: A. the study of behavior and customs B. digging up bones to study the evolution of the human species C. the comparison of cultures in order to identify similarities and differences of patterning D. the analysis of the weaving of tapestry 2. Culture can be defined as: A. a set of ideas and meanings that people use based on the past and by which they construct the present B. symphony orchestras and opera C. the knowledge about yourself and your past that you’re born with and is transmitted through your genes D. all of the above 3. Society is A. the same thing as culture B. -

Heather Richards- Rissetto

HEATHER RICHARDS- RISSETTO Current as of 06/13/2020 Department of Anthropology 840 Oldfather Hall University of Nebraska-Lincoln ph. 402.472.2420 Lincoln, NE 68588 [email protected] CURRENT POSITION 2020-Present Associate Professor of Anthropology, School of Global Integrative Studies, University of Nebraska-Lincoln 2014-2020 Assistant Professor of Anthropology, School of Global Integrative Studies, University of Nebraska-Lincoln 2014-Present Faculty Fellow, Center for Digital Research in the Humanities, University of Nebraska- Lincoln 2016-Present Courtesy Assistant Professor, School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska- Lincoln 2019-Present Museum Research Associate, University of Nebraska State Museum 2020 Interim Digital Humanities Program Coordinator, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Nebraska-Lincoln PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT 2013-2014 Geographic Information Systems Teaching Fellow, Dept. of Geography, Middlebury College, Vermont 2012-2013 NSF Postdoctoral Fellow, 3D Optical Metrology, Bruno Kessler Foundation, Trento, Italy 2010-2014 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Dept. of Anthropology, University of New Mexico EDUCATION Ph.D. University of New Mexico, Ph.D. with Distinction, Anthropology (2010). Advisors: James Boone, Jane Buikstra, Jennifer von Schwerin, David Dinwoodie, and Richard Watson M.A. University of New Mexico, M.A., Anthropology B.A. University of Southern Maine, B.A., Anthropology and Geography TOPICAL CONCENTRATIONS & SKILLS -Geographic Information Systems -3D Visualization -Mesoamerica -Ancient -

ALABAMA® University Libraries

THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA® University Libraries Engaging Undergraduates through Neuroanthropological Research Christopher D. Lynn – University of Alabama, Max J. Stein – University of Alabama, and Andrew P.C. Bishop – Arizona State University Deposited 2/21/2018 Citation of published version: Lynn, C.D., Stein, M.J., Bishop, A.P.C. (2016). Engaging Undergraduates through Neuroanthropological Research. Anthropology Now, 6(1), 92-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/19492901.2013.11728423 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Anthropology Now on 17 May 2016, available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/19492901.2013.11728423. © Taylor & Francis AnthroNow_6-1_AnthroNow 2/25/14 10:29 AM Page 92 education in the “neuroanthropology” of religion through a project that develops new appli- cations for the study of religious commit- Engaging Undergraduates ment and the psychology of dissociation, through affirms scientific inquiry and empowers stu- Neuroanthropological dents to become active researchers. We present this project from the varied perspec- Research tives of a professor and undergraduate men- tor (Lynn), a graduate student and assistant Christopher D. Lynn, Max J. Stein in undergraduate training (Stein) and a and Andrew P. C. Bishop graduate student trained through this pro- gram (Bishop). nthropology’s holistic way of viewing Aand interpreting the world is an asset to The Neuroanthropology “Brand” any college graduate. It helps put global and local events in context and grounds this Neuroanthropology is an increasingly popu- context in particularistic and scientifically lar specialty that combines ethnography meaningful frames. Nevertheless, the disci- with neuroscience to understand the brain pline is frequently beset by skepticism of its in culture. -

Current Anthropology Fonds

Current Anthropology fonds Compiled by Erwin Wodarczak (2015) University of British Columbia Archives Table of Contents Fonds Description o Title / Dates of Creation / Physical Description o Administrative History o Custodial History o Scope and Content o Notes Series Descriptions o Sol Tax (Editor) o Rejected Articles o Accepted Publications o Duplicate Files o Editorial Files o CA – General o CA – Accounts o University of Chicago Press Box List Catalogue entry (UBC Library catalogue) Fonds Description Current Anthropology fonds. – 1970-1985. 32.03 m of textual records. Administrative History The journal Current Anthropology is a peer-reviewed academic journal, published by the University of Chicago Press and sponsored by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. Founded in 1959, it is devoted to research that covers the full range of scholarship on human cultures and on the human and other primate species. Current Anthropology publishes research across all sub-disciplines of anthropology, including social, cultural, and physical anthropology, as well as ethnology and ethnohistory, archaeology and prehistory, folklore, and linguistics. Cyril Belshaw, of the UBC Department of Anthropology and Sociology, was editor of Current Anthropology from 1975 to 1985. Custodial History Materials were originally donated to the University Archives by Cyril Belshaw as part of his personal fonds in 1985. With the donation by Belshaw of the rest of his papers in 2015 the fonds was re-organized, and the Current Anthropology records were removed and established as a separate fonds. Scope and Content Fonds consists of editorial files and related materials accumulated by Cyril Belshaw as editor of Current Anthropology. -

An Anthropology of Repatriation: Contemporary Physical Anthropological and Native American Ontologies of Practice

Whittier College Poet Commons Anthropology Faculty Publications & Research 2012 An Anthropology of Repatriation: Contemporary Physical Anthropological and Native American Ontologies of Practice Ann M. Kakaliouras Follow this and additional works at: https://poetcommons.whittier.edu/anth Part of the Anthropology Commons S210 Current Anthropology Volume 53, Supplement 5, April 2012 An Anthropology of Repatriation Contemporary Physical Anthropological and Native American Ontologies of Practice by Ann M. Kakaliouras The policies and politics around the repatriation of ancestral human remains and biological materials to Native North Americans and other indigenous peoples have largely been rooted in attempts to reconcile divergent worldviews about cultural heritage. Even though repatriation has been a legal and practical reality for over 2 decades, controversies between anthropological scientists and repatriation proponents still often dominate professional and scholarly dis- courses over the fate of Native American human remains and associated artifacts. The epistemological gap between Western scientific and indigenous or Native American perspectives—however crucial to bridge in the process of consultation and achieving mutual agreements—is likely to remain. Moreover, although it is a productive legal, sociopolitical, and cultural strategy for many indigenous groups, repatriation as practiced still struggles to funda- mentally transform anthropology’s relationship to indigenous peoples, at least in the United States. In this article I will