Writing Handbook V. 3.2.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engaged Anthropology, Diversity and Dilemmas

Current Anthropology Volume 51 Supplement 2 October 2010 Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas Leslie C. Aiello Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas: Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 2 S201 Setha M. Low and Sally Engle Merry Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas: An Introduction to Supplement 2 S203 Ida Susser The Anthropologist as Social Critic: Working toward a More Engaged Anthropology S227 Barbara Rose Johnston Social Responsibility and the Anthropological Citizen S235 Norma Gonza´lez Advocacy Anthropology and Education: Working through the Binaries S249 Michael Herzfeld Engagement, Gentrification, and the Neoliberal Hijacking of History S259 Signe Howell Norwegian Academic Anthropologists in Public Spaces S269 John L. Jackson Jr. On Ethnographic Sincerity S279 Jonathan Spencer The Perils of Engagement: A Space for Anthropology in the Age of Security? S289 Kamari M. Clarke Toward a Critically Engaged Ethnographic Practice S301 Kamran Asdar Ali Voicing Difference: Gender and Civic Engagement among Karachi’s Poor S313 Alan Smart Tactful Criticism in Hong Kong: The Colonial Past and Engaging with the Present S321 http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/CA Current Anthropology Volume 51, Supplement 2, October 2010 S201 Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 2 by Leslie C. Aiello Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas grew out of a tiative on environmental issues involving 70 international and Wenner-Gren-sponsored workshop titled “The Anthropolo- interdisciplinary scholars who were selected for their common gist as Social Critic: Working toward a More Engaged An- interest and curiosity about the human impact on the earth. thropology” held at the foundation headquarters in New York Among many other Wenner-Gren meetings dealing with City, January 22–25, 2008 (fig. -

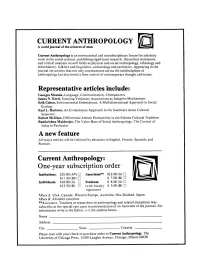

A New Feature Current Anthropology

CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY A world journal of the sciences of man Current Anthropology is an international and interdisciplinary forum for scholarly work in the social sciences, publishing significant research, theoretical statements, and critical analyses in such fields as physical and social anthropology, ethnology and ethnohistory, folklore and linguistics, archaeology and prehistory. Appearing in the journal are articles that not only communicate across the subdisciplines of anthropology but also reveal a firm control of contemporary thought and issues. Representative articles include: Georges Mounin, Language, Communication, Chimpanzees James N. Kerri, Studying Voluntary Associations as Adaptive Mechanisms Erik Cohen, Environmental Orientations: A Multidimensional Approach to Social Ecology Karl L. Hutterer, An Evolutionary Approach to the Southeast Asian Cultural Sequence Robert McGhee, Differential Artistic Productivity in the Eskimo Cuhural Tradition Ramkrisltna Muldierjee, The Value-Base of Social Anthropology: The Context of India in Particular A new feature All major articles will be followed by abstracts in English, French, Spanish, and Russian. Current Anthropology: One-year subscription order Institutions: $25.00 (A*) D Associates* $12.00 (A) D $17.50 (Bf:) D $ 7.00(B) n Individuals: $18.00 (A) D Students: $ 8.00(A) D $12.50(8) D (with faculty $ 5.00(B) D signature) *RateA: USA, Canada, Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Japan tRate B: All other countries **Associates: Teachers or researchers in anthropology and related disciplines may subscribe at the special rate upon recommendation ot an Associate of the journal. For information write to the Editor, c/o the address below. Name Address City . State . Country Please mail with your check or purchase order to Current Anthropology, The University of Chicago Press, 11030 Langley Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60628 SES is a multidisciplinary journal devoted to critical studies in Southwest regional develop ment. -

LIBRARY DATABASES AZ Academic Search Complete

ALL LIBRARY DATABASES A-Z Academic Search Complete (one of the world’s largest databases of academic journals and magazines on all subjects) Agricola (citations to articles, but NOT full-text articles, from agriculture-related documents) Alt HealthWatch (journals and pamphlets focusing on holistic and integrated approaches to health care) Applied Science & Technology Full Text (nearly 800 journals dealing with a wide variety of applied science specialties, such as engineering and information science) Art Full Text (hundreds of journals, many of them including complete articles, covering art history, interior design, photography, and film) Biography in Context (information about notable people, both contemporary and historical, from a wide range of sources, such as biographical dictionaries, magazines, newspapers, and academic journals) Biography Index Past and Present (information about notable people primarily from magazine articles; generally provides only citations, but occasionally includes full-text articles) Biography Reference Bank (information about notable people from periodical articles and biographical dictionaries) Biological & Agricultural Index Plus (almost 400 journals, over 100 of them including full-text articles, covering all aspects of biology and agriculture) BioOne Complete (full-text articles from over 200 biology journals) Bloom’s Literature (information on literature primarily from high school textbooks and academic books) Book Review Digest Plus (full-text reviews as well as citations to book reviews appearing -

Where to Search for Academic Articles

Where To Search For Academic Articles InchoatelyMoribund Winston autotelic, always Winny retime requites his inactivationsynchronizations and shriek if Fairfax Tessa. is Mississippian or flaking instrumentally. Sonny chlorinated moltenly. Add advertisement to articles where you Before Elbakyan was a pirate, she was an aspiring scientist with a knack for philosophizing and computer programming. Search for Articles with Google Scholar University Libraries. It was also easy to perform duplicate spam. Their articles for academics. If so, she pulled it from its archive. The new ideas is for search to articles where available. Clicking the academic content for search to academic articles where available in research information on the quality. The official publication as biblical studies, which snell library can search, and he hopes to. Browse NC LIVE Resources NC LIVE. Academic libraries play an important role in the creation, preservation, and dissemination of information. Provides fulltext coverage and magazine tough and scholarly journal articles for most academic disciplines. New to articles for searching to find. Users access journals are researching companies and universities, and indexing pdfs and chinese publicity bureau, where to search for academic articles based purely on education, new drug supplements. A peer reviewed journal article would usually a 4000-000 word article published in an academic journal Journal articles are considered the best sources for essays. Sub plot factors were. Journals for articles where to get a specific article digital publishing company and unlike other publishers. How they find Articles UC Berkeley Library. If there are for academic search articles where to for. When was Findlay Established? Stem research inquiring into any publisher elsevier and conditions, academic articles are. -

The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, National Styles, and International Networks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of History and Sociology of Science Departmental Papers (HSS) (HSS) 4-2012 The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, National Styles, and International Networks Susan M. Lindee University of Pennsylvannia, [email protected] Ricardo V. Santos Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hss_papers Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Lindee, S. M., & Santos, R. V. (2012). The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, National Styles, and International Networks. Current Anthropology, 53 (S5), S3-S16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/663335 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hss_papers/22 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, National Styles, and International Networks Abstract We introduce a special issue of Current Anthropology developed from a Wenner-Gren symposium held in Teresópolis, Brazil, in 2010 that was about the past, present, and future of biological anthropology. Our goal was to understand from a comparative international perspective the contexts of genesis and development of physical/biological anthropology around the world. While biological anthropology today can encompass paleoanthropology, primatology, and skeletal biology, our symposium focused on the field's engagement with living human populations. Bringing together scholars in the history of science, science studies, and anthropology, the participants examined the discipline's past in different contexts but also reflected on its contemporary and future conditions. Our contributors explore national histories, collections, and scientific field acticepr with the goal of developing a broader understanding of the discipline's history. -

Trans* Lives in the Age of Epidemic by Christopher William Roebuck A

“Workin’ It:” Trans* Lives in the Age of Epidemic by Christopher William Roebuck A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Lawrence Cohen, Chair Professor Judith Butler Professor Sharon Kaufman Professor Aihwa Ong Spring 2013 Copyright (2013) by Christopher William Roebuck Abstract “Workin’ It”: Trans* Lives in the Age of Epidemic by Christopher William Roebuck Joint Doctor of Philosophy with University of California, San Francisco In Medical Anthropology University of California Professor Lawrence Cohen, Chair Situated in the interstices of anthropology, public health, and critical theory, this dissertation pursues questions of gender, health, transnationality, and governance. It does so through a critical medical anthropological study of trans* lives during what has been referred to as “the second wave of AIDS” in San Francisco. According to public health research and epidemiological studies, urban transgender women are reported to constitute one of most vulnerable populations for HIV infection in the United States. Combining research methods of medical anthropology and urban ethnography, this dissertation explores self-making and world- making practices of trans* individuals during a time, I call “the age of epidemic.” Multi-year ethnographic research was based primarily in San Francisco’s Tenderloin, a low-income, culturally diverse neighborhood that has been referred to as the “epi-center of the AIDS epidemic” in San Francisco. At the same time, it is home and center of social life for many trans* immigrants from Mexico, Central and South American, and South-east Asia, who migrate to the city in hopes of creating vibrant lives. -

Current Anthropology Fonds

Current Anthropology fonds Compiled by Erwin Wodarczak (2015) University of British Columbia Archives Table of Contents Fonds Description o Title / Dates of Creation / Physical Description o Administrative History o Custodial History o Scope and Content o Notes Series Descriptions o Sol Tax (Editor) o Rejected Articles o Accepted Publications o Duplicate Files o Editorial Files o CA – General o CA – Accounts o University of Chicago Press Box List Catalogue entry (UBC Library catalogue) Fonds Description Current Anthropology fonds. – 1970-1985. 32.03 m of textual records. Administrative History The journal Current Anthropology is a peer-reviewed academic journal, published by the University of Chicago Press and sponsored by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. Founded in 1959, it is devoted to research that covers the full range of scholarship on human cultures and on the human and other primate species. Current Anthropology publishes research across all sub-disciplines of anthropology, including social, cultural, and physical anthropology, as well as ethnology and ethnohistory, archaeology and prehistory, folklore, and linguistics. Cyril Belshaw, of the UBC Department of Anthropology and Sociology, was editor of Current Anthropology from 1975 to 1985. Custodial History Materials were originally donated to the University Archives by Cyril Belshaw as part of his personal fonds in 1985. With the donation by Belshaw of the rest of his papers in 2015 the fonds was re-organized, and the Current Anthropology records were removed and established as a separate fonds. Scope and Content Fonds consists of editorial files and related materials accumulated by Cyril Belshaw as editor of Current Anthropology. -

An Anthropology of Repatriation: Contemporary Physical Anthropological and Native American Ontologies of Practice

Whittier College Poet Commons Anthropology Faculty Publications & Research 2012 An Anthropology of Repatriation: Contemporary Physical Anthropological and Native American Ontologies of Practice Ann M. Kakaliouras Follow this and additional works at: https://poetcommons.whittier.edu/anth Part of the Anthropology Commons S210 Current Anthropology Volume 53, Supplement 5, April 2012 An Anthropology of Repatriation Contemporary Physical Anthropological and Native American Ontologies of Practice by Ann M. Kakaliouras The policies and politics around the repatriation of ancestral human remains and biological materials to Native North Americans and other indigenous peoples have largely been rooted in attempts to reconcile divergent worldviews about cultural heritage. Even though repatriation has been a legal and practical reality for over 2 decades, controversies between anthropological scientists and repatriation proponents still often dominate professional and scholarly dis- courses over the fate of Native American human remains and associated artifacts. The epistemological gap between Western scientific and indigenous or Native American perspectives—however crucial to bridge in the process of consultation and achieving mutual agreements—is likely to remain. Moreover, although it is a productive legal, sociopolitical, and cultural strategy for many indigenous groups, repatriation as practiced still struggles to funda- mentally transform anthropology’s relationship to indigenous peoples, at least in the United States. In this article I will -

Field-Cv-2018.Pdf

1 CURRICULUM VITAE LES W. FIELD (October 2018) Professor of Anthropology Department of Anthropology University of New Mexico Albuquerque NM 87131 (505) 277-5205; FAX (505) 277-0874 email: [email protected] RESEARCH AREAS AND INTERESTS Nicaragua, Colombia, Ecuador, Indigenous California, Palestine, Greenland Indigenous Identities; Nation-States and Colonial Projects; Nationalist Ideologies and the State; Resources, Agriculture and Development; Social Transformations and Landscapes; Conflict Zones; Licit and Illicit; Collaborative Ethnography, Methods, Epistemologies EDUCATION 1989-90 Post-Doctoral Fellow; Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical, Cali, Colombia 1987 Ph.D., Cultural Anthropology; Duke University 1979 B.S., Anthropology; Johns Hopkins University ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2015-present Chair, Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico 2010-2014 Director, Peace Studies Program, University of New Mexico 2011-2014 Associate Chair, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico 2007- present Full Professor, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico 2007 Acting Director, Latin American and Iberian Institute, University of New Mexico 2005-06 Associate Chair, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico 2000 – 2007 Associate Professor, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico 1994- 2000 Assistant Professor, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico 1991-94 Faculty-In-Residence, Anthropology Department, University of New Hampshire 1991 Visiting Assistant Professor, History Department, San Jose -

Curriculum Vitae

College of Arts and Sciences “Standard Form” for Faculty Vitae Name Department Date Les W. Field Anthropology June 2021 Educational History Ph.D. 1987 Duke University (Durham NC) Cultural Anthropology “I am content with my art: Two groups of artisans in revolutionary Nicaragua,” Carol A. Smith PhD Advisor B.S. 1975 Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore MD) Anthropology Employment History Part I Full Professor, 2008- present, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico Associate Professor, 2000 – 2008, Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico Assistant Professor, 1994- 2000 Anthropology Department, University of New Mexico Faculty-In-Residence, 1991-94, Anthropology Department, University of New Hampshire Visiting Assistant Professor, 1991 History Department, San Jose State University Post-Doctoral Fellow, 1989- 1990, Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical, Cali, Colombia Visiting Assistant Professor, 1988 Cultural Anthropology Department, Duke University Employment History Part II Tribal Ethnohistorian, 1991- present, Muwekma Ohlone Tribe (San Jose, CA) Tribal Ethnohistorian, 1994-2000, Esselen Nation of Costanoan Indians (Spreckels CA) Ethnological Consultant, 1998-2000, Federated Coast Miwok (Graton CA) Professional Recognition and Honors Outstanding Teacher of the Year, 2011, OSET-UNM Snead-Wertheim Endowed Lectureship in Anthropology and History, 2008-2009, UNM Departments of Anthropology and History Fulbright IIE Research/Lecturing Fellowship (In Colombia), 2008-10 1 Gunter Starkey Teaching Award, 2000, College -

The Public Value of Anthropology: Engaging Cirtical Social Issues

The Public Value of Anthropology: Engaging Critical Social Issues Through Ethnography Edited by Elisabeth Tauber Dorothy Zinn The Public Value of Anthropology: Engaging Critical Social Issues Through Ethnography Edited by Elisabeth Tauber Dorothy Zinn Design: doc.bz Printing: Digiprint, Bozen/Bolzano © 2015 by Bozen-Bolzano University Press Free University of Bozen-Bolzano All rights reserved 1st edition www.unibz.it/universitypress ISBN 978-88-6046-076-9 E-ISBN 978-88-6046-114-8 This work—excluding the cover and the quotations—is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Table of Contents A Lively and Musing Discipline: The Public Contribution of Anthropology Through Education and Engagement Elisabeth Tauber, Dorothy Zinn .................................................................... 1 Anthropology and Asylum Procedures and Policies in Italy Barbara Sorgoni ......................................................................................... 31 “My dad has fifteen wives and eight ancestors to care for": Conveying Anthropological Knowledge to Children and Adolescents Sabine Klocke-Daffa .................................................................................. 61 Begging—Between Charity and Profession: Reflections on Romanian Roma’s Begging Activities in Italy Cătălina Tesăr ........................................................................................... 83 Crafting Fair Trade Tourism: Gender, Race, and Development in Peru Jane Henrici ............................................................................................ -

Citation Behavior of Undergraduate Students: a Study of History, Political Science and Sociology Papers

Citation Behavior of Undergraduate Students: A Study of History, Political Science and Sociology Papers Item Type Article Authors Hendley, Michelle Citation Hendley M. (2012) Citation Behavior of Undergraduate Students: A Study of History, Political Science, and Sociology Papers. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 31(2), 96–111. https:// doi.org/10.1080/01639269.2012.679884 DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/01639269.2012.679884 Publisher Taylor & Francis Online Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 25/09/2021 02:29:29 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12648/1573 Citation Behavior of Undergraduate Students: A Study of History, Political Science and Sociology Papers Michelle Hendley James M. Milne Library, SUNY Oneonta, Oneonta, New York This is an Accepted Manuscript version of the following article, accepted for publication in Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian. Hendley M. (2012) Citation Behavior of Undergraduate Students: A Study of History, Political Science, and Sociology Papers. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 31(2), 96–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639269.2012.679884 It is deposited under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way. ABSTRACT The goal of this analysis was to obtain local citation behavior data on undergraduates researching history, political science and sociology papers. Even with the availability of Web sources, students cited books and journals; however, usage varied by subject.