143 4. the CIAC in CONTEXT 4.1 Introduction This Chapter Bridges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: from Pittura

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas ISSN: 0185-1276 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas México AGUIRRE, MARIANA Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917- 1928 Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, vol. XXXV, núm. 102, 2013, pp. 93-124 Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36928274005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MARIANA AGUIRRE laboratorio sensorial, guadalajara Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917-1928 lthough the art of the Bolognese painter Giorgio Morandi has been showcased in several recent museum exhibitions, impor- tant portions of his trajectory have yet to be analyzed in depth.1 The factA that Morandi’s work has failed to elicit more responses from art historians is the result of the marginalization of modern Italian art from the history of mod- ernism given its reliance on tradition and closeness to Fascism. More impor- tantly, the artist himself favored a formalist interpretation since the late 1930s, which has all but precluded historical approaches to his work except for a few notable exceptions.2 The critic Cesare Brandi, who inaugurated the formalist discourse on Morandi, wrote in 1939 that “nothing is less abstract, less uproot- ed from the world, less indifferent to pain, less deaf to joy than this painting, which apparently retreats to the margins of life and interests itself, withdrawn, in dusty kitchen cupboards.”3 In order to further remove Morandi from the 1. -

ARTE CONCETTUALE in ITALIA Libri D’Artista E Cataloghi 1965 - 1985 in Copertina (Particolare): N

ARTE CONCETTUALE IN ITALIA libri d’artista e cataloghi 1965 - 1985 in copertina (particolare): n. 27. Renato Mambor. Vocabolario degli usi, Roma, Galleria Breton, 1971 ARTE CONCETTUALE IN ITALIA libri d’artista e cataloghi 1965 - 1985 NOVEMBER PROGRAM Sunday, November 1, 2020: Conceptual art in Italy - invitations and posters Saturday, November 7, 2020: Conceptual art in Italy - Artist’s books and catalogs Saturday, November 14, 2020: Arte Oggettuale, Kinetic and Minimal in Italy. Invitations, Posters, catalogs and books. Saturday, November 21, 2020: Arte Povera 1967-1978 - Artist’s books, ca- talogs, invitations, posters, photos and original documents 1. AA.VV., La Tartaruga - Catalogo 2, Roma, la Tartaruga Galleria di Pittura e Scultura Contempora- nee, 1965 (Febbraio), 30,5x23,5 cm., brossura, pp. 28 (incluse le copertine), copertina illustrata con immagine fotografica in bianco e nero, 44 illustrazioni in bianco e nero con opere di Mario Ceroli (10 immagini), Pino Pascali (4 immagini), Giosetta Fioroni, Nanni Balestrini, Ilja Josifovic Kabakov, Eric Vladimirovic Bulatov, Ulo Sooster e immagini fotografiche di artisti e personaggi famosi presenti alla Premiazione della Prima Edizione del Premio la Tartaruga (ottobre 1964) fra cui Alberto Moravia, Achille Perilli, Dacia Maraini, Leoncillo, Leonardo Sinisgalli, Taylor Mead, Michelangelo Antonioni e molti altri. testi di Maurizio Calvesi “(Mario Ceroli) Dritto e rovescio”, Cesare Vivaldi “(Pino Pascali) Un mito mediterraneo”, Nanni Balestrini “Quartina per Giosetta”. Edizione originale. € 120 2. BARUCHELLO Gianfranco (Livorno 1924), Mi viene in mente. Romanzo, Milano, Edizioni Galle- ria Schwarz, 1966, 24x16,5 cm, brossura con sovraccopertina in acetato, pp. [112], libro d’artista interamente illustrato con disegni al tratto e testi calligrafi a stampa dell’artista. -

UNFOLDING of HISTORY. AGOSTINO BONALUMI, SANDRO DE ALEXANDRIS” Curated by Marco Meneguzzo

MILAN GALLERIA 10 A.M. ART FROM 10 JUNE TO 30 SEPTEMBER 2021 “UNFOLDING OF HISTORY. AGOSTINO BONALUMI, SANDRO DE ALEXANDRIS” curated by Marco Meneguzzo From 10 June to 30 September the Galleria 10 A.M. ART in Milan is organising the show Unfolding of history. Agostino Bonalumi, Sandro De Alexandris. In the show an important selection of works from the 1960s and 1970s will open a new dialogue between the researches of the two artists. This is what the curator, Marco Meneguzzo, has written: The habit of looking at a certain kind of reading of history – all histories – is usually generated by a very convincing interpretation of what has happened, and also of the inevitable generalisations that the distance in time from the events produces in those very interpretations. The history of art, which is made of individuals as well as of languages, is not immune from these generalisations and habits: the cataloguing by movements and by successive phases really is convenient (from the viewpoint of scholastic or frivolous divulgation) and allows the placing of each work of an artist in the place that news and the universally known attribute to them, and thus to define them once and for all, in such a way as to make clear what we are speaking about and anyway the territory in which we move. Luckily, history is a dynamic affair that, even without resorting to impossible revisionism, in the urgency of defining certain important moments of its course – important for us, not for history in itself which is indifferent –, together with generalisations, searches the opposite pole in order to refine its own view, to make it more acute until it finds the various underground rivers of its own course which, on the one hand, shift from the principle current and, on the other, perhaps finds in another direction part of that current that was held to run calmly to the mouth. -

Scarica Catalogo

1 2 Renata Boero 3 Renata Boero Testo critico Marilena Pasquali Traduzioni David Stanton, Milano Apparati Sara Meloni Referenze fotografiche Industrialfoto, Firenze Stampa Raa © 2011 Cardelli & Fontana artecontemporanea Via Torrione Stella Nord 5, 19038 Sarzana (SP) T/F 0187 626374 [email protected] www.cardelliefontana.com © 2011 Colossi Arte Contemporanea Corsia del Gambero 12/13, 25121 Brescia T 030 3758583 [email protected] www.colossiarte.it © 2011 Galleria Open Art Viale della Repubblica 24, 59100 Prato T 0574 538003 F 0574 537808 [email protected] www.openart.it © 2011 Galleria Spazia Via dell’Inferno 5, 40126 Bologna T 051 220184 F 051 222333 [email protected] ISBN 000-00-000-000-0 www.galleriaspazia.com Tutti i diritti sono riservati 4 Renata Boero Testo critico di Marilena Pasquali 5 6 7 8 Sommario / Contents 11 Renata Boero. I Cromogrammi come 113 Senza tempo filtri del tempo Luca Beatrice Marilena Pasquali 119 Renata Boero 18 Renata Boero. I Cromogrammi come Claudio Cerritelli filtri del tempo Marilena Pasquali 131 L’inevitabile magnetismo Tommaso Trini Antologia critica 134 La terra dell’anima 50 Solve et coagula Raffaele Morelli Luciano Caramel 139 Per Renata 71 La pittura dimenticata a memoria Giuseppe Frazzetto Achille Bonito Oliva 142 La concreta ligereza del ser 76 Boero Donatella Cannova Filiberto Menna Apparati / Appendix 77 Per Renata Boero Marco Meneguzzo 153 Biografia 90 Cucine 160 Biography Paolo Fossati 165 Esposizioni / Exhibitions 98 De sensu rerum et magia 170 Libri-opera / Art Books Marisa Vescovo 171 Bibliografia / Bibliography 9 Ipotesi di piegature n.5-. Studio sulla trasformazione cromatica della turmic alla verifica esterna, 1976 10 Renata Boero. -

Michele Dantini, Gradus Ad Parnassum. Giulio Paolini, “Autoritratto”, 1969, in “Palinsesti

Michele Dantini, Gradus ad Parnassum. Giulio Paolini, “Autoritratto”, 1969, in “Palinsesti. Contemporary Italian Art On-Line Journal”, vol. 1, n. 2, 2011, pp. 1-11. Nel 1969 Giulio Paolini realizza un singolare Autoritratto “turchesco”: poco visto, poco noto, pressoché dimenticato persino dall’artista (fig. 1). Ricorre a una fotografia in bianco e nero anonima, casuale, trovata chissà dove. L’immagine dell’Autoritratto non ha niente a che fare con l’aspetto dell’artista: mostra un anziano dagli abiti in apparenza orientali, dall’atteggiamento smarrito. Ha grande barba, turbante e scarpette. Alle sue spalle un ampio portale in bronzo modellato in profondità e ornato di motivi a racemi, inserito tra imponenti pilastri in marmo. Un sufi, un ex Giovane turco in gita sul Bosforo, un pittore-pellegrino appassionato e schivo con cartelletta e ombrellino parasole oppure Giovanni Bellini redivivo? Non sappiamo, né disponiamo di alcuna biografia. Ma all’immagine giova lo statuto di relitto: dilapidata dal tempo, i fortuiti passaggi di mano e l’eccessiva esposizione alla luce, è un documento di cui è andato perduto l’archivio. Il retino fotografico, bene in vista, lascia supporre che l’immagine sia il dettaglio isolato e ingrandito di una vecchia cartolina. QUALE TRADIZIONE? Due sole evidenze ci sorreggono nella nostra indagine. La prima: l’anziano è un pittore, per questo desta l’interesse di Paolini. Esibisce infatti diligenti attributi del mestiere. La seconda: all’affaticato sgomento dello sguardo contribuisce non poco il confronto, impari, tra le proprie capacità e la soggiogante eredità ricevuta. Il portale si chiude alle spalle quasi a sospingere fuori, o a vietare l’accesso. -

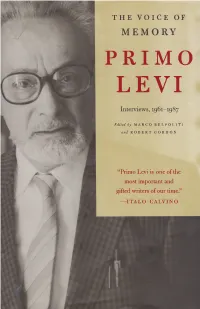

Primo-Levi-The-Voice-Of-Memory

THE VOICE OF MEMORY PRIMO LEVI Interviews, 1961-1987 Edited by M A R C 0 B E L P 0 L I T I and R 0 B E R T G 0 R D 0 N "Primo Levi is one of the most important and gifted writers of our time." -ITALO CALVINO The Voice of Memory The Voice of Memory Interviews 1961-1987 Primo Levi Edited by Marco Belpoliti and Robert Gordon Translated by Robert Gordon The New Press New York This collection © 2001 by Polity Press First published in Italy as Primo Levi: Conversazioni e interviste 1963-87, edited by Marco Belpoliti © 1997 Guilio Einaudi, 1997, with the exception of the interviews beginning on pages 3, 13, 23, and 34 (for further details see Acknowledgments page). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. First published in the United Kingdom by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2001 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2001 Distributed by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York ISBN 1-56584-645-1 (he.) CIP data available. The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450West 41st Street, 6th floor, NewYork, NY 10036 www.thenewpress.com Set in Plantin Printed in the -

Syllabus Toschi 2018

! ARTH-UA9850 Class code Instructor Details Name: CATERINA TOSCHI NYUHome Email Address: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesday: 1:00pm – 2:30pm; Thursday: 1:00pm – 2:30pm (appointment arranged via email) Villa Sassetti: TBA Villa Ulivi Office Extension: 055 5007 300 For fieldtrips refer to the email with trip instructions and trip assistant’s cell phone number Semester: Spring 2018 Class Details Full Title of Course: Modern Movements in Italian Art: 1861 – Present Day Meeting Days and Times: Tuesday 3:00pm – 5:45pm; Thursday 3:00pm – 5:45pm Classroom Location: Villa Sassetti – TBA Attendance, Academic Integrity Prerequisites Sample Page 1! of 18! The course aims to examine modern movements of Italian Art from the Unity in Class Description 1861 to present day exploring key turning points and breakthroughs. Given the extent of the period analyzed, a chronology of the topics addressed in class can be consulted at the following link: 20th and 21st-Century Art History, ed. Caterina Toschi, http://timemapper.okfnlabs.org/toschicaterina/20th-and-21st-century-art- history--ed-caterina-toschi. Video and photographic materials of the recent Italian artistic culture will also be uploaded on the course’s website throughout the semester to invite students to think about contemporary through history, and vice versa, from the outset. Each topic is addressed thanks to different tools: 1. Lectures: to illustrate the Italian art system and its complex evolution in the 20th century with a focus on Tuscan artistic culture. 2. Manifestos and documentary resources: to stimulate students to confront with a philological methodology by learning to interpret and understand art history through document. -

LUCIANO FABRO Biography

P A U L AC O O P E R G A L L E R Y LUCIANO FABRO Biography Born. 1936. Turin, Italy Died: 2007. Milan, Italy Awards: 2004 Accademico d’onore, Accademia di Belle Arti, Florence, 2004 1994 Coutts Contemporary Art Award, Zurich 1994 1993 Premio Antonio Feltrinelli awarded by the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Rome, 1993 1987 Sikkens Prize given by the Sikkens Stichting, Rotterdam, 1987 1983 Art Prize, Aachen, given by The Ludwig Forum, Aachen, 1983 1981 Louis-Price Award, 1981 Teaching: Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara, Carrara, Italy 1979 - 1982 Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, Milan, Italy 1983 - 2002 Selected One-Person Exhibitions: 2019 C’est la vie, Casamadre arte contemporanea Gallery, Naples, Italy 2017 Luciano Fabro, Simon Lee Gallery, London, UK 2016 Luciano Fabro, Micheline Szwajcer Gallery, Bruxelles, Belgium 2015 Luciano Fabro, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York Fabro, Christian Stein Gallery, Milan, Italy Fabro, Casamadre arte contemporanea Gallery, Naples, Italy 2014 Luciano Fabro, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain 2013 Luciano Fabro. Disegno In-Opera, GAMeC, Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Bergamo, Italy; Centro Italiano Arte Contemporanea (CIAC), Foligno, Italy Luciano Fabro: 100 disegni, Kunstmuseum Winterthur, Zurich, Switzerland 2009 À Luciano Fabro, Progetti Gallery, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2008 Permanent installation: Il cielo di Gennaro, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina (MADRE), Naples, Italy 2007 Luciano Fabro e amici, Galerie Lelong, Zurich, Switzerland Luciano Fabro, Didactica Magna Minima Moralia, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina (MADRE), Naples, Italy Preview: Colonna di Genk, Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht, Netherlands 524 WEST 26TH STREET, NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10001 TELEPHONE 212.255.1105 FACSIMILE 212.255.5156 P A U L AC O O P E R G A L L E R Y 2005 Permanent installation: Il cielo di Gennaro, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina (MADRE), Naples, Italy Permanent installation: Luciano Fabro. -

MEMOFONTE Rivista On-Line Semestrale

STUDI DI MEMOFONTE Rivista on-line semestrale Numero 24/2020 FONDAZIONE MEMOFONTE Studio per l’elaborazione informatica delle fonti storico-artistiche www.memofonte.it COMITATO REDAZIONALE Proprietario Fondazione Memofonte onlus Fondatrice Paola Barocchi Direzione scientifica Donata Levi Comitato scientifico Francesco Caglioti, Barbara Cinelli, Flavio Fergonzi, Margaret Haines, Donata Levi, Nicoletta Maraschio, Carmelo Occhipinti Cura redazionale Martina Nastasi, Mara Portoghese Segreteria di redazione Fondazione Memofonte onlus, via de’ Coverelli 2/4, 50125 Firenze [email protected] ISSN 2038-0488 INDICE LUCIO ORIANI Un libro d’ore miniato da Cristoforo Majorana alla Biblioteca dei Girolamini di Napoli p. 1 CAMILLA FROIO La cultura nord-americana e il Laokoon di G.E. Lessing: premesse di una fortunata ricezione critica (1840-1874) p. 23 EMANUELE PELLEGRINI Una Rivista attraverso il Novecento p. 61 FLAVIO FERGONZI Una polemica tra Francesco Arcangeli e Cesare Vivaldi sulla pittura moderna (1958-1960) p. 76 GIULIA CAPPELLETTI Un cambio di passo: la partecipazione italiana alla VII Biennale di Parigi del 1971 p. 113 GIOVANNI RUBINO Munari 1971. Il progetto critico di Paolo Fossati per Codice Ovvio: un libro d’artista di massa p. 145 CRISTIANA SORRENTINO Santarcangelo 1980, Festival del Teatro in Piazza. Nuovi metodi di indagine sui rapporti tra fotografia e teatro e uno sguardo nell’Archivio Carla Cerati p. 183 CARMEN BELMONTE La Sapienza, il fascismo, una mostra. Snodi critici nella ricezione dell’arte del Ventennio negli anni Ottanta p. 208 GIORGIO BACCI Arti migranti. Uno sguardo attuale a partire dal tema della barca p. 245 ARTE & LINGUA MATTEO MAZZONE Su un tecnicismo dell’architettura di area settentrionale: il verbo salicare/saligare (‘selciare’) p. -

Manfredo Tafuri and Storia Dell'architettura Italiana, 1944-1985’

CENTRE FOR ARCHITECTURE I THEORY I CRITICISM I HISTORY ATCH Author Leach, Andrew Title ‘”Everything we do is but the larvae of our intentions": Manfredo Tafuri and Storia Dell'Architettura Italiana, 1944-1985’ Date 2002 Source Additions to Architectural History: XIXth Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand ISBN 1864996471 www.uq.edu.au/atch ADDITIONS to architectural history XIXth conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand, Brisbane: SAHANZ, 2002 ‘Everything we do is but the larva of our intentions’: Manfredo Tafuri and Storia dell’architettura italiana 1944-1985 ɴʀ ʟʜ Wellington Institute of Technology This paper offers a critical reading of the Manfredo Tafuri’s Storia dell’architettura italiana 1944-1985. Besides a small body of monographic writing, Storia dell’architettura italiana remains Tafuri’s single broad assessment of the polemics of post-War Italian architectural culture. Given its contemporaneity with Tafuri’s own life and career, this paper questions the text’s ‘operative’ dimension. It likewise identifies and questions Tafuri’s absence as ‘actor’ within the text in terms of his ‘authority’ as a writer. Does absence play an active role in the text? Responding to these questions involves an emerging body of ideas attending to Tafuri’s positions on the tasks of history and criticism. Post-War Italian intellectual history sheds further light on a dialectic of knowledge and action significant to Tafuri’s historiographic programme from the late 1960s onwards. The relationship of Storia dell’architettura italiana to Teorie e storia dell’architettura and Progetto e utopia is consequently questioned. -

Living Art and the Art of Living

LIVING ART AND THE ART OF LIVING: REMAKING HOME IN ITALY IN THE 1960s Teresa Kittler PhD Thesis History of Art University College London 2014 1 DECLARATION I, Teresa Kittler, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on the social, material, and aesthetic engagement with the image of home by artists in Italy in the 1960s to offer new perspectives on this period that have not been accounted for in the literature. It considers the way in which the shift toward environment, installation and process-based practices mapped onto the domestic at a time when Italy had become synonymous with the design of environments. Over four chapters I explore the idea of living-space as the mise-en-scène, and conceptual framework, for a range of artists working across Italy in ways that both anticipate and shift attention away from accounts that foreground the radical architectural experiments enshrined in MoMA’s landmark exhibition Italy: the New Domestic Landscape (1972). I begin by examining the way in which the group of temporary homes made by Carla Accardi between 1965 and 1972 combines the familiar utopian rhetoric of alternative living with attempts to redefine artistic practice at this moment. I then go on to look in turn at the sculptural practice of artists Marisa Merz and Piero Gilardi in relation to the everyday lived experience of home. This question is first considered in relation to the material and psychic challenges Merz poses to the gendering of homemaking with Untitled (Living Sculpture) 1966. -

Saint Paul and a Group of Worshippers

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Bernardo Daddi active by 1320, died probably 1348 Saint Paul and a Group of Worshippers 1333 tempera on panel painted surface: 224.8 × 77 cm (88 1/2 × 30 5/16 in.) overall: 233.53 × 88.8 × 5.3 cm (91 15/16 × 34 15/16 × 2 1/16 in.) Inscription: above the saint's halo: S[ANCTUS]; above the saint's shoulders: PAU LUS; on the lower frame below the worshippers: [ANNO DOMI]NI.MCCCXXXIII M...II.ESPLETUM FUIT H[O]C OPUS (In the year of the Lord 1333... this work was finished) [1] Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.3 ENTRY The panel, with the frontal figure of the standing saint, who is not accompanied to the sides by a series of superimposed narrative scenes of his legend as in so- called biographical icons, belongs to a type of image that began to appear in Florence and in other cities in Italy in the thirteenth century and remained widespread throughout the following century: narrow and elongated in format, these paintings were probably intended to be hung against a pillar in a church. [1] Paintings of this kind, however, were more frequently painted directly onto the pillar or onto the wall of the church with the more economical technique of fresco. [2] Panels with single figures of saints were realized either with a votive intention, as for instance the one by Daddi himself representing Saint Catherine of Alexandria and a kneeling donor, now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence, [3] or as an expression of the cult of a confraternity or a religious lay company that met to pray and sing before the image at particular times.