Redalyc.Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: from Pittura

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Giulio Paolini and Giorgio De Chirico Explored for Cima's

GIULIO PAOLINI AND GIORGIO DE CHIRICO EXPLORED FOR CIMA’S 2016-17 SEASON Dual-focus Exhibition Reveals Unexplored Ties between Artists, Including Metaphysical Masterpieces by de Chirico Not Seen in U.S. in 50 Years, And Installation, Sculpture, and New Series of Works on Paper by Paolini From Left to Right: Giorgio de Chirico, Le Muse Inquietanti, 1918. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome. Giulio Paolini, Controfigura (critica del punto vista), 1981. © Giulio Paolini. Courtesy of Fondazione Giulio e Anna Paolini. New York, NY (April 5, 2016) – This October, the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA)’s annual installation will take a focused look at the direct ties between two Italian artists born in different centuries but characterized by deep affinities: the founder of Metaphysical painting, Giorgio de Chirico (1888- 1978), and leading conceptual artist Giulio Paolini (b. 1940). With a long-held interest in de Chirico’s oeuvre, Paolini often quotes signature motifs from the earlier artist’s works, despite defying de Chirico’s traditional painterly methods. As evidenced in CIMA’s installation, Paolini has appropriated certain of de Chirico’s meditations on the nature of representation, acknowledging him as a precursor of postmodernism. By juxtaposing important works by both artists in “conversation,” CIMA’s 2016-17 season will present a new appreciation of de Chirico’s metaphysical art and its lasting relevance. On view October 7, 2016 through June 24, 2017, Giorgio de Chirico – Giulio Paolini / Giulio Paolini – Giorgio de Chirico will be the fourth presentation mounted by CIMA, which promotes public appreciation for and new scholarship in 20th-century Italian art through annual installations, public programming, and its fellowship program. -

Parcours Pédagogique Collège Le Cubisme

PARCOURS PÉDAGOGIQUE COLLÈGE 2018LE CUBISME, REPENSER LE MONDE LE CUBISME, REPENSER LE MONDE COLLÈGE Vous trouverez dans ce dossier une suggestion de parcours au sein de l’exposition « Cubisme, repenser le monde » adapté aux collégiens, en Un autre rapport au préparation ou à la suite d’une visite, ou encore pour une utilisation à distance. réel : Ce parcours est à adapter à vos élèves et ne présente pas une liste d’œuvres le traitement des exhaustive. volumes dans l’espace Ce dossier vous propose une partie documentaire présentant l’exposition, suivie d’une sélection d’œuvres associée à des questionnements et à des compléments d’informations. L’objectif est d’engager une réflexion et des échanges avec les élèves devant les œuvres, autour de l’axe suivant « Un autre rapport au réel : le traitement des volumes dans l’espace ». Ce parcours est enrichi de pistes pédadogiques, à exploiter en classe pour poursuivre votre visite. Enfin, les podcasts conçus pour cette exposition vous permettent de préparer et d’approfondir in situ ou en classe. Suivez la révolution cubiste de 1907 à 1917 en écoutant les chroniques et poèmes de Guillaume Apollinaire. Son engagement auprès des artistes cubistes n’a jamais faibli jusqu’à sa mort en 1918 et a nourri sa propre poésie. Podcasts disponibles sur l’application gratuite du Centre Pompidou. Pour la télécharger cliquez ici, ou flashez le QR code situé à gauche. 1. PRÉSENTATION DE L’EXPOSITION L’exposition offre un panorama du cubisme à Paris, sa ville de naissance, entre 1907 et 1917. Au commencement deux jeunes artistes, Georges Braque et Pablo Picasso, nourris d’influences diverses – Gauguin, Cézanne, les arts primitifs… –, font table rase des canons de la représentation traditionnelle. -

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Published on Iitaly.Org (

Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Natasha Lardera (February 21, 2014) On view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, until September 1st, 2014, this thorough exploration of the Futurist movement, a major modernist expression that in many ways remains little known among American audiences, promises to show audiences a little known branch of Italian art. Giovanni Acquaviva, Guillaume Apollinaire, Fedele Azari, Francesco Balilla Pratella, Giacomo Balla, Barbara (Olga Biglieri), Benedetta (Benedetta Cappa Marinetti), Mario Bellusi, Ottavio Berard, Romeo Bevilacqua, Piero Boccardi, Umberto Boccioni, Enrico Bona, Aroldo Bonzagni, Anton Giulio Bragaglia, Arturo Bragaglia, Alessandro Bruschetti, Paolo Buzzi, Mauro Camuzzi, Francesco Cangiullo, Pasqualino Cangiullo, Mario Carli, Carlo Carra, Mario Castagneri, Giannina Censi, Cesare Cerati, Mario Chiattone, Gilbert Clavel, Bruno Corra (Bruno Ginanni Corradini), Tullio Crali, Tullio d’Albisola (Tullio Mazzotti), Ferruccio Demanins, Fortunato Depero, Nicolaj Diulgheroff, Gerardo Dottori, Fillia (Luigi Page 1 of 3 Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Colombo), Luciano Folgore (Omero Vecchi), Corrado Govoni, Virgilio Marchi, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Alberto Martini, Pino Masnata, Filippo Masoero, Angiolo Mazzoni, Torido Mazzotti, Alberto Montacchini, Nelson Morpurgo, Bruno Munari, N. Nicciani, Vinicio Paladini -

André Derain Stoppenbach & Delestre

ANDR É DERAIN ANDRÉ DERAIN STOPPENBACH & DELESTRE 17 Ryder Street St James’s London SW1Y 6PY www.artfrancais.com t. 020 7930 9304 email. [email protected] ANDRÉ DERAIN 1880 – 1954 FROM FAUVISM TO CLASSICISM January 24 – February 21, 2020 WHEN THE FAUVES... SOME MEMORIES BY ANDRÉ DERAIN At the end of July 1895, carrying a drawing prize and the first prize for natural science, I left Chaptal College with no regrets, leaving behind the reputation of a bad student, lazy and disorderly. Having been a brilliant pupil of the Fathers of the Holy Cross, I had never got used to lay education. The teachers, the caretakers, the students all left me with memories which remained more bitter than the worst moments of my military service. The son of Villiers de l’Isle-Adam was in my class. His mother, a very modest and retiring lady in black, waited for him at the end of the day. I had another friend in that sinister place, Linaret. We were the favourites of M. Milhaud, the drawing master, who considered each of us as good as the other. We used to mark our classmates’s drawings and stayed behind a few minutes in the drawing class to put away the casts and the easels. This brought us together in a stronger friendship than students normally enjoy at that sort of school. I left Chaptal and went into an establishment which, by hasty and rarely effective methods, prepared students for the great technical colleges. It was an odd class there, a lot of colonials and architects. -

Giorgio De Chirico and Rafaello Giolli

345 GIORGIO DE CHIRICO AND RAFFAELLO GIOLLI: PAINTER AND CRITIC IN MILAN BETWEEN THE WARS AN UNPUBLISHED STORY Lorella Giudici Giorgio de Chirico and Rafaello Giolli: “one is a painter, the other a historian”,1 Giolli had pointed out to accentuate the diference, stung to the quick by statements (“just you try”2) and by the paintings that de Chirico had shown in Milan in early 1921, “pictures […] which”, the critic declared without mincing words, “are not to our taste”.3 Te artist had brought together 26 oils and 40 drawings, including juvenilia (1908- 1915) and his latest productions, for his frst solo show set up in the three small rooms of Galleria Arte,4 the basement of an electrical goods shop that Vincenzo Bucci5 more coherently and poetically rechristened the “hypogean gallery”6 and de Chirico, in a visionary manner, defned as “little underground Eden”.7 Over and above some examples of metaphysical painting, de Chirico had shown numerous copies of renaissance and classical works, mostly done at the Ufzi during his stays in Florence: a copy from Dosso Dossi and a head of Meleager (both since lost); Michelangelo’s Holy Family (“I spent six months on it, making sure to the extent of my abilities to render the aspect of Michelangelo’s work in its colour, its clear and dry impasto, in the complicated spirit of its lines and forms”8); a female fgure, in Giolli’s words “unscrupulously cut out of a Bronzino picture”,9 and a drawing with the head of Niobe, as well as his Beloved Young Lady, 1 R. -

Futurism's Photography

Futurism’s Photography: From fotodinamismo to fotomontaggio Sarah Carey University of California, Los Angeles The critical discourse on photography and Italian Futurism has proven to be very limited in its scope. Giovanni Lista, one of the few critics to adequately analyze the topic, has produced several works of note: Futurismo e fotografia (1979), I futuristi e la fotografia (1985), Cinema e foto- grafia futurista (2001), Futurism & Photography (2001), and most recently Il futurismo nella fotografia (2009).1 What is striking about these titles, however, is that only one actually refers to “Futurist photography” — or “fotografia futurista.” In fact, given the other (though few) scholarly studies of Futurism and photography, there seems to have been some hesitancy to qualify it as such (with some exceptions).2 So, why has there been this sense of distacco? And why only now might we only really be able to conceive of it as its own genre? This unusual trend in scholarly discourse, it seems, mimics closely Futurism’s own rocky relationship with photography, which ranged from an initial outright distrust to a later, rather cautious acceptance that only came about on account of one critical stipulation: that Futurist photography was neither an art nor a formal and autonomous aesthetic category — it was, instead, an ideological weapon. The Futurists were only able to utilize photography towards this end, and only with the further qualification that only certain photographic forms would be acceptable for this purpose: the portrait and photo-montage. It is, in fact, the very legacy of Futurism’s appropriation of these sub-genres that allows us to begin to think critically about Futurist photography per se. -

ARTE CONCETTUALE in ITALIA Libri D’Artista E Cataloghi 1965 - 1985 in Copertina (Particolare): N

ARTE CONCETTUALE IN ITALIA libri d’artista e cataloghi 1965 - 1985 in copertina (particolare): n. 27. Renato Mambor. Vocabolario degli usi, Roma, Galleria Breton, 1971 ARTE CONCETTUALE IN ITALIA libri d’artista e cataloghi 1965 - 1985 NOVEMBER PROGRAM Sunday, November 1, 2020: Conceptual art in Italy - invitations and posters Saturday, November 7, 2020: Conceptual art in Italy - Artist’s books and catalogs Saturday, November 14, 2020: Arte Oggettuale, Kinetic and Minimal in Italy. Invitations, Posters, catalogs and books. Saturday, November 21, 2020: Arte Povera 1967-1978 - Artist’s books, ca- talogs, invitations, posters, photos and original documents 1. AA.VV., La Tartaruga - Catalogo 2, Roma, la Tartaruga Galleria di Pittura e Scultura Contempora- nee, 1965 (Febbraio), 30,5x23,5 cm., brossura, pp. 28 (incluse le copertine), copertina illustrata con immagine fotografica in bianco e nero, 44 illustrazioni in bianco e nero con opere di Mario Ceroli (10 immagini), Pino Pascali (4 immagini), Giosetta Fioroni, Nanni Balestrini, Ilja Josifovic Kabakov, Eric Vladimirovic Bulatov, Ulo Sooster e immagini fotografiche di artisti e personaggi famosi presenti alla Premiazione della Prima Edizione del Premio la Tartaruga (ottobre 1964) fra cui Alberto Moravia, Achille Perilli, Dacia Maraini, Leoncillo, Leonardo Sinisgalli, Taylor Mead, Michelangelo Antonioni e molti altri. testi di Maurizio Calvesi “(Mario Ceroli) Dritto e rovescio”, Cesare Vivaldi “(Pino Pascali) Un mito mediterraneo”, Nanni Balestrini “Quartina per Giosetta”. Edizione originale. € 120 2. BARUCHELLO Gianfranco (Livorno 1924), Mi viene in mente. Romanzo, Milano, Edizioni Galle- ria Schwarz, 1966, 24x16,5 cm, brossura con sovraccopertina in acetato, pp. [112], libro d’artista interamente illustrato con disegni al tratto e testi calligrafi a stampa dell’artista. -

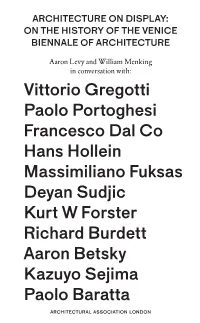

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Monuments to Mundanity at the Socle Du Monde Biennale | Apollo

REVIEWS Monuments to mundanity at the Socle du Monde Biennale Nausikaä El-Mecky 28 APRIL 2017 Socle du Monde (1961), Piero Manzoni. Photo: Ole Bagger. Courtesy of HEART SHARE TWITTER FACEBOOK LINKEDIN EMAIL I am in the middle of nowhere and absolutely terrified. All around me, long strips of white canvas stretch into the distance, suspended above the grass; the wind plays them like strings, making them howl and snap. They are precisely at the level of my neck, and their edges appear razor-sharp. Walking through Keisuke Matsuura’s brilliantly simple Resonance, with its multiple slacklines stretched across two small rises, is like going through a dangerous portal, or navigating a set of laser-beams. Keisuke Matsuura resonance Socle du Monde Biennale 2017 from Keisuke Matsuura on Vimeo. Matsuura’s work is part of the 7th Socle du Monde Biennale in Herning, Denmark. To get there, we drive through an industrial estate in the middle of grey flatlands. Steam billows from a chimney nearby, and a massive hardware store flanks the Biennale’s terrain, which consists of manicured green lawns dotted with several buildings, and intercut by a road or two. Rather than ruining the experience, the encroaching elements of daily life make for a compelling, unpretentious backdrop to the art on display. Matsuura’s work is typical of this Biennale, where things that appear simple, even mundane, suddenly swallow you up in an intense encounter. Even the main building, Denmark’s HEART museum, is a surprise. At first glance it appears to be an unobtrusive, white-walled specimen of Scandi minimalism, but when I happen to look up, I see a beautifully menacing ceiling whose folds and texture resemble parchment or flesh. -

GIORGIO MORANDI 5 – 26 March 2016 Tuesday to Sunday – 2 Pm to 7Pm Via Serlas 35, CH-75000, St Moritz

GIORGIO MORANDI 5 – 26 March 2016 Tuesday to Sunday – 2 pm to 7pm Via Serlas 35, CH-75000, St Moritz ROBILANT+VOENA are pleased to present an exhibition of paintings by Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964) on view at their St Moritz gallery from 5-26 of March 2016. This will be the second exhibition at the gallery dedicated to the celebrated Italian artist, following the 2011 show ‘Still Life’ held at their London space. The exhibition will include works the artist realised during the 1940s and 1960s, bringing together a selection of eight landscapes and still lifes. Morandi was a unique, poetic and challenging artist renowned for his subtle and contemplative paintings which, despite the repetition of subject-matter, are extremely complex in their organisation and execution. Throughout the course of his extensive and very prolific career, Morandi remained committed to developing a deliberately limited visual language. In doing so he concentrated almost exclusively on the production of still lifes and landscapes, repeatedly making use of the same familiar subject-objects: bottles, vases, boxes, flowers or the same landscape views, taken from the window of his home on Via Fondazza or in Grizzana. Included in this exhibition are two Flower paintings produced ten years apart (in 1943 and 1953) and two Still Lifes, from 1949/1950 and 1959. Whilst these paintings are characterised by simplicity of composition, great sensitivity to tone, colour, light and compositional balance, it is possible to notice in his later works a shift in focus, which tends to fade and gradually dissolve the material. In addition, the show will feature four paintings from his Landscape series. -

Futurism-Anthology.Pdf

FUTURISM FUTURISM AN ANTHOLOGY Edited by Lawrence Rainey Christine Poggi Laura Wittman Yale University Press New Haven & London Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College. Frontispiece on page ii is a detail of fig. 35. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Scala type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Futurism : an anthology / edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-08875-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Futurism (Art) 2. Futurism (Literary movement) 3. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Rainey, Lawrence S. II. Poggi, Christine, 1953– III. Wittman, Laura. NX456.5.F8F87 2009 700'.4114—dc22 2009007811 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: F. T. Marinetti and the Development of Futurism Lawrence Rainey 1 Part One Manifestos and Theoretical Writings Introduction to Part One Lawrence Rainey 43 The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909) F.