Saint Paul and a Group of Worshippers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: from Pittura

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas ISSN: 0185-1276 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas México AGUIRRE, MARIANA Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917- 1928 Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, vol. XXXV, núm. 102, 2013, pp. 93-124 Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36928274005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MARIANA AGUIRRE laboratorio sensorial, guadalajara Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917-1928 lthough the art of the Bolognese painter Giorgio Morandi has been showcased in several recent museum exhibitions, impor- tant portions of his trajectory have yet to be analyzed in depth.1 The factA that Morandi’s work has failed to elicit more responses from art historians is the result of the marginalization of modern Italian art from the history of mod- ernism given its reliance on tradition and closeness to Fascism. More impor- tantly, the artist himself favored a formalist interpretation since the late 1930s, which has all but precluded historical approaches to his work except for a few notable exceptions.2 The critic Cesare Brandi, who inaugurated the formalist discourse on Morandi, wrote in 1939 that “nothing is less abstract, less uproot- ed from the world, less indifferent to pain, less deaf to joy than this painting, which apparently retreats to the margins of life and interests itself, withdrawn, in dusty kitchen cupboards.”3 In order to further remove Morandi from the 1. -

ARTE CONCETTUALE in ITALIA Libri D’Artista E Cataloghi 1965 - 1985 in Copertina (Particolare): N

ARTE CONCETTUALE IN ITALIA libri d’artista e cataloghi 1965 - 1985 in copertina (particolare): n. 27. Renato Mambor. Vocabolario degli usi, Roma, Galleria Breton, 1971 ARTE CONCETTUALE IN ITALIA libri d’artista e cataloghi 1965 - 1985 NOVEMBER PROGRAM Sunday, November 1, 2020: Conceptual art in Italy - invitations and posters Saturday, November 7, 2020: Conceptual art in Italy - Artist’s books and catalogs Saturday, November 14, 2020: Arte Oggettuale, Kinetic and Minimal in Italy. Invitations, Posters, catalogs and books. Saturday, November 21, 2020: Arte Povera 1967-1978 - Artist’s books, ca- talogs, invitations, posters, photos and original documents 1. AA.VV., La Tartaruga - Catalogo 2, Roma, la Tartaruga Galleria di Pittura e Scultura Contempora- nee, 1965 (Febbraio), 30,5x23,5 cm., brossura, pp. 28 (incluse le copertine), copertina illustrata con immagine fotografica in bianco e nero, 44 illustrazioni in bianco e nero con opere di Mario Ceroli (10 immagini), Pino Pascali (4 immagini), Giosetta Fioroni, Nanni Balestrini, Ilja Josifovic Kabakov, Eric Vladimirovic Bulatov, Ulo Sooster e immagini fotografiche di artisti e personaggi famosi presenti alla Premiazione della Prima Edizione del Premio la Tartaruga (ottobre 1964) fra cui Alberto Moravia, Achille Perilli, Dacia Maraini, Leoncillo, Leonardo Sinisgalli, Taylor Mead, Michelangelo Antonioni e molti altri. testi di Maurizio Calvesi “(Mario Ceroli) Dritto e rovescio”, Cesare Vivaldi “(Pino Pascali) Un mito mediterraneo”, Nanni Balestrini “Quartina per Giosetta”. Edizione originale. € 120 2. BARUCHELLO Gianfranco (Livorno 1924), Mi viene in mente. Romanzo, Milano, Edizioni Galle- ria Schwarz, 1966, 24x16,5 cm, brossura con sovraccopertina in acetato, pp. [112], libro d’artista interamente illustrato con disegni al tratto e testi calligrafi a stampa dell’artista. -

Bertoia, Harry

237 East Palace Avenue Santa Fe, NM 87501 800 879-8898 505 989-9888 505 989-9889 Fax [email protected] Harry Bertoia (American Sculptor and Designer, 1915-1978) Arieto Bertoia was born on March 10, 1915, in the small village of San Lorenzo, Friuli, Italy, about 50 miles north of Venice and 70 miles south of Austria. He had one brother, Oreste, and one sister, Ave. Another sister died at eighteen months old; she was the subject of one of his first paintings. Even as a youngster, the local brides would ask him to design their wedding day linen embroidery patterns, as his talents were already recognized. He attended high school in Arzene, Carsara, until age 15. He then accompanied his father to Detroit to visit his brother Oreste. Upon entering North America, his birth name Arri, which often morphed into the nickname Arieto ("little Harry" in Italian), was altered to the Americanized "Harry." Bertoia stayed in Michigan to attend Cass Technical High School, a public school with a special program for talented students in arts and sciences. Later, a one-year scholarship to the Art School of the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts allowed him to study painting and drawing. He entered and placed in many local art competitions. By the fall of 1937, another scholarship entitled him to become a student, again of painting and drawing, at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. Cranbrook was, at the time, an amazing melting pot of creativity attracting many famous artists and designers: Carl Milles, resident-sculptor, Maija Grotell, resident-ceramist, Walter Gropius, visiting Bauhaus- architect, and others. -

Faithful Friends

Valentiner Meyers Given 24 Water Weasels DETROIT SUNDAY TIMES C April 8. 1945—Part I, Page 11 Dr. Friends . Good Housekeeping Faithful“/ pray thee, give them me, that birds to gentle, unto which the Scripture likeneth chaste and humble In Carriers’ Bag and faithful souls, may not fall into the hands of TABLE PADf Quit cruel To Post men that would kill them”—St Francis Assisi. Knudsen Post Stop chances with your Ml Times Boys Near taklnf table. Be sale, be tare with Art Institute Head Detroit Officer Half Way Mark a Good Housekeeping table Old Masters Authority pad. None better made, none Succeeds General better fitted. Nu-wood grain One Water Weasel short of their patterns William R. Valentiner, with choice of colors half way mark! Detroit Times and soil felt back. Priced fromIMP tor of the Detroit Art Insti- An army career officer will suc- t carriers Saturday had purchased Let our representative measure lute, by some ceed Gen. William S. Knudsen. and considered the Lt 24 Water Weasels and havg 26 to your table and show «am. world’s on M ¦BHg : production pies of foremoat authority old former automotive go to reach their goal ... 50 heat-proof, liquid- proof and masters, will retire this month. geniu* of General Motors Corp., Water Weasels purchased for the washable table pads. his wife, of the air technical Shop at koms by Dr. Valentiner and as director army through calling TR 2-1455, day Cecilia, are at their newly en- service command May 1. 24 Bought the sale of war or night. -

UNFOLDING of HISTORY. AGOSTINO BONALUMI, SANDRO DE ALEXANDRIS” Curated by Marco Meneguzzo

MILAN GALLERIA 10 A.M. ART FROM 10 JUNE TO 30 SEPTEMBER 2021 “UNFOLDING OF HISTORY. AGOSTINO BONALUMI, SANDRO DE ALEXANDRIS” curated by Marco Meneguzzo From 10 June to 30 September the Galleria 10 A.M. ART in Milan is organising the show Unfolding of history. Agostino Bonalumi, Sandro De Alexandris. In the show an important selection of works from the 1960s and 1970s will open a new dialogue between the researches of the two artists. This is what the curator, Marco Meneguzzo, has written: The habit of looking at a certain kind of reading of history – all histories – is usually generated by a very convincing interpretation of what has happened, and also of the inevitable generalisations that the distance in time from the events produces in those very interpretations. The history of art, which is made of individuals as well as of languages, is not immune from these generalisations and habits: the cataloguing by movements and by successive phases really is convenient (from the viewpoint of scholastic or frivolous divulgation) and allows the placing of each work of an artist in the place that news and the universally known attribute to them, and thus to define them once and for all, in such a way as to make clear what we are speaking about and anyway the territory in which we move. Luckily, history is a dynamic affair that, even without resorting to impossible revisionism, in the urgency of defining certain important moments of its course – important for us, not for history in itself which is indifferent –, together with generalisations, searches the opposite pole in order to refine its own view, to make it more acute until it finds the various underground rivers of its own course which, on the one hand, shift from the principle current and, on the other, perhaps finds in another direction part of that current that was held to run calmly to the mouth. -

"Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2017 "Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto: An Analysis of Illusory and Spiritual Depth Aaron Hubbell Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Hubbell, Aaron, ""Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto: An Analysis of Illusory and Spiritual Depth" (2017). LSU Master's Theses. 4408. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4408 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THINGS NOT SEEN" IN THE FRESCOES OF GIOTTO: AN ANALYSIS OF ILLUSORY AND SPIRITUAL DEPTH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University and the School of Art in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History in The School of Art by Aaron T. Hubbell B.F.A., Nicholls State University, 2011 May 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Elena Sifford, of the College of Art and Design for her continuous support and encouragement throughout my research and writing on this project. My gratitude also extends to Dr. Darius Spieth and Dr. Maribel Dietz as the additional readers of my thesis and for their valuable comments and input. -

Scarica Catalogo

1 2 Renata Boero 3 Renata Boero Testo critico Marilena Pasquali Traduzioni David Stanton, Milano Apparati Sara Meloni Referenze fotografiche Industrialfoto, Firenze Stampa Raa © 2011 Cardelli & Fontana artecontemporanea Via Torrione Stella Nord 5, 19038 Sarzana (SP) T/F 0187 626374 [email protected] www.cardelliefontana.com © 2011 Colossi Arte Contemporanea Corsia del Gambero 12/13, 25121 Brescia T 030 3758583 [email protected] www.colossiarte.it © 2011 Galleria Open Art Viale della Repubblica 24, 59100 Prato T 0574 538003 F 0574 537808 [email protected] www.openart.it © 2011 Galleria Spazia Via dell’Inferno 5, 40126 Bologna T 051 220184 F 051 222333 [email protected] ISBN 000-00-000-000-0 www.galleriaspazia.com Tutti i diritti sono riservati 4 Renata Boero Testo critico di Marilena Pasquali 5 6 7 8 Sommario / Contents 11 Renata Boero. I Cromogrammi come 113 Senza tempo filtri del tempo Luca Beatrice Marilena Pasquali 119 Renata Boero 18 Renata Boero. I Cromogrammi come Claudio Cerritelli filtri del tempo Marilena Pasquali 131 L’inevitabile magnetismo Tommaso Trini Antologia critica 134 La terra dell’anima 50 Solve et coagula Raffaele Morelli Luciano Caramel 139 Per Renata 71 La pittura dimenticata a memoria Giuseppe Frazzetto Achille Bonito Oliva 142 La concreta ligereza del ser 76 Boero Donatella Cannova Filiberto Menna Apparati / Appendix 77 Per Renata Boero Marco Meneguzzo 153 Biografia 90 Cucine 160 Biography Paolo Fossati 165 Esposizioni / Exhibitions 98 De sensu rerum et magia 170 Libri-opera / Art Books Marisa Vescovo 171 Bibliografia / Bibliography 9 Ipotesi di piegature n.5-. Studio sulla trasformazione cromatica della turmic alla verifica esterna, 1976 10 Renata Boero. -

Michele Dantini, Gradus Ad Parnassum. Giulio Paolini, “Autoritratto”, 1969, in “Palinsesti

Michele Dantini, Gradus ad Parnassum. Giulio Paolini, “Autoritratto”, 1969, in “Palinsesti. Contemporary Italian Art On-Line Journal”, vol. 1, n. 2, 2011, pp. 1-11. Nel 1969 Giulio Paolini realizza un singolare Autoritratto “turchesco”: poco visto, poco noto, pressoché dimenticato persino dall’artista (fig. 1). Ricorre a una fotografia in bianco e nero anonima, casuale, trovata chissà dove. L’immagine dell’Autoritratto non ha niente a che fare con l’aspetto dell’artista: mostra un anziano dagli abiti in apparenza orientali, dall’atteggiamento smarrito. Ha grande barba, turbante e scarpette. Alle sue spalle un ampio portale in bronzo modellato in profondità e ornato di motivi a racemi, inserito tra imponenti pilastri in marmo. Un sufi, un ex Giovane turco in gita sul Bosforo, un pittore-pellegrino appassionato e schivo con cartelletta e ombrellino parasole oppure Giovanni Bellini redivivo? Non sappiamo, né disponiamo di alcuna biografia. Ma all’immagine giova lo statuto di relitto: dilapidata dal tempo, i fortuiti passaggi di mano e l’eccessiva esposizione alla luce, è un documento di cui è andato perduto l’archivio. Il retino fotografico, bene in vista, lascia supporre che l’immagine sia il dettaglio isolato e ingrandito di una vecchia cartolina. QUALE TRADIZIONE? Due sole evidenze ci sorreggono nella nostra indagine. La prima: l’anziano è un pittore, per questo desta l’interesse di Paolini. Esibisce infatti diligenti attributi del mestiere. La seconda: all’affaticato sgomento dello sguardo contribuisce non poco il confronto, impari, tra le proprie capacità e la soggiogante eredità ricevuta. Il portale si chiude alle spalle quasi a sospingere fuori, o a vietare l’accesso. -

Art and Science Come Together in Detroit Institute of Arts' Exhibition "Bruegel's the Wedding Dance Revealed" !

AiA News-Service Art and science come together in Detroit Institute of Arts' exhibition "Bruegel's The Wedding Dance Revealed" ! Expert Dr. Tomasz Wazny (Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun) assesses the edge of wood panel of The Wedding Dance as part of the dendrochronological analysis. DETROIT, MICH.- The Detroit Institute of Arts invites visitors to experience an exhibition that explores how science and technology is used to learn about art, focused on one of the DIA’s most iconic European paintings. “Bruegel’s The Wedding Dance Revealed” is open from December 14, 2019–August 30, 2020. The year 2019 marks the 450th anniversary of artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s death, and to commemorate it, the DIA’s Conservation department and the European Art department collaborated to trace the life of the painting from its creation in 1566 to the present, including the story behind the DIA’s exciting acquisition of the work in 1930. This exhibition is free with museum admission, which is always free for residents of Macomb, Oakland and Wayne counties. The DIA was the second museum in the U.S. to acquire a painting by Bruegel, and it soon became one of the museum’s most prized and beloved works. This exhibition features three other works from the DIA’s collection, as well as conservation images (x-ray and infrared), archival materials, pigments and a variety of tools inspired by Bruegel’s complex quest to source and create the colors used in the painting. The exhibition is located in Special Exhibitions Central, adjacent to the Detroit Industry murals. -

Curriculum Simona Pasquinucci

CURRICULUM DOTT.SSA SIMONA PASQUINUCCI Simona Pasquinucci è nata a Empoli (Fi) il 6 aprile 1965. Titoli di studio: Maturità Classica presso il Liceo Ginnasio “Niccolò Forteguerri” di Pistoia nel 1983 con la votazione di 60/60; Laurea in Lettere presso l’Università degli Studi di Firenze relatore Prof. Mina Gregori nel 1991 con una tesi dal titolo “Giovanni Bonsi nella pittura Fiorentina della metà del Trecento” con la votazione di 110 /110 e lode; Diploma in Archivistica, Paleografia e Diplomatica presso l’Archivio di Stato di Firenze nel 1993 con la votazione di 63/70. Specializzazione in Beni Artistici conseguita presso la Scuola di Studi Umanistici e della Formazione di Firenze il 18 aprile 2019 con il massimo dei voti e menzione della lode. Esperienza professionale: Dal 27 luglio 1997 in servizio presso l’Amministrazione dei Beni Culturali (prima presso la Soprintendenza Beni Artistici e Storici per le Province di Firenze Pistoia e Prato, fino alla riforma del 2014 presso il Polo Museale Fiorentino; Polo Museale Regionale della Toscana fino al 30 giugno 2016); Dal primo luglio 2016 assegnata alle Gallerie degli Uffizi, con la qualifica di Assistente Amministrativo; Dal 14 luglio 2019 nomina a Storico dell’Arte. Capodivisione Curatoriale delle Gallerie degli Uffizi dal 2019 ad oggi. Attività scientifica: Fa parte del Consiglio direttivo dell’Associazione Corpus della Pittura Fiorentina. Ha iniziato nel 1991 la sua collaborazione con il Corpus della Pittura Fiorentina, sotto la guida del Prof. Miklos Boskovits, lavorando al volume, uscito nel 2000, “Tradition and Innovation in florentine Trecento Painting Giovanni Bonsi and Tommaso del Mazza” nel quale sono confluite le ricerche condotte per la tesi di laurea. -

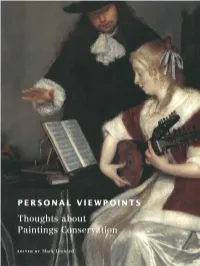

Thoughts About Paintings Conservation This Page Intentionally Left Blank Personal Viewpoints

PERSONAL VIEWPOINTS Thoughts about Paintings Conservation This page intentionally left blank Personal Viewpoints Thoughts about Paintings Conservation A Seminar Organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, June 21-22, 2001 EDITED BY Mark Leonard THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE LOS ANGELES & 2003 J- Paul Getty Trust THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Timothy P. Whalen, Director Los Angeles, CA 90049-1682 Jeanne Marie Teutónico, Associate Director, www.getty.edu Field Projects and Science Christopher Hudson, Publisher The Getty Conservation Institute works interna- Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief tionally to advance conservation and to enhance Tobi Levenberg Kaplan, Manuscript Editor and encourage the preservation and understanding Jeffrey Cohen, Designer of the visual arts in all of their dimensions— Elizabeth Chapín Kahn, Production Coordinator objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through Typeset by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Austin, Texas scientific research; education and training; field Printed in Hong Kong by Imago projects; and the dissemination of the results of both its work and the work of others in the field. Library of Congress In all its endeavors, the Institute is committed Cataloging-in-Publication Data to addressing unanswered questions and promoting the highest possible standards of conservation Personal viewpoints : thoughts about paintings practice. conservation : a seminar organized by The J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, June 21-22, 2001 /volume editor, Mark Leonard, p. -

Daddi, Bernardo Also Known As Daddo, Bernardo Di Active by 1320, Died Probably 1348

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Paintings Daddi, Bernardo Also known as Daddo, Bernardo di active by 1320, died probably 1348 BIOGRAPHY Son of Daddo di Simone, Bernardo is recorded for the first time in the registers of the Arte dei Medici e Speziali when he enrolled in the guild (which also included artists) between 1312 and 1320.[1] By this date he must have been a firmly established painter, as the reconstruction of his oeuvre also suggests; presumably, he had been born by the last decade of the thirteenth century, if not earlier. His first securely dated work is the signed triptych in the Uffizi, Florence; its inscription contains not only the artist’s name but also the year 1328. Recent studies, however, have assigned various works, also of large dimensions, to previous years, such as the cycle of frescoes in the chapel of the Pulci and Berardi families in Santa Croce in Florence; the polyptych of San Martino at Lucarelli (Siena), now in the New Orleans Museum of Art; and the polyptych divided among the Galleria Nazionale in Parma, the Museo Lia in La Spezia, and a private collection.[2] Although perhaps trained in the circle of painters such as Lippo di Benivieni or the Master of San Martino alla Palma,[3] in the second or the early third decade of the fourteenth century Bernardo worked in close contact with Giotto’s shop (executing for the church of Santa Croce, then the preserve of the pupils and followers of the great master, not only the abovementioned frescoes but also possibly the Parma–La Spezia polyptych).[4] During the fourth and fifth decades of the century, Daddi’s shop seems to have produced by preference numerous small but precious panels destined for private devotion.