Non-Wood Forest Products and Services for Socio-Economic Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUINEE - PREFECTURE DE NZEREKORE Carte De La Population Et Des Structures Sanitaires 10 Mars 2021

GUINEE - PREFECTURE DE NZEREKORE Carte de la population et des structures sanitaires 10 mars 2021 BEYLA KOUANKAN BOOLA Boola Kognea Maghana Lomou Ouinzou Kogbata FOUMBADOU SEREDOU Boma Nord Gbana KOROPARA Lomou Gounangalaye Saouro Kpamou Koni Koropara Lokooua Alaminata Foozou Nyema Nord Kabieta Bassa´ta Koroh Keleta Ouleouon WOMEY Pampara Suobaya Bowe Nord NZEBELA Keorah Womey kerezaghaye Zenemouta Beneouli Selo MACENTA Loula Yomata Koule Komata KOULE Pale Yalakpala Tokpata Goueke Voumou LAINE Tamoe Niaragbaleye Kpoulo Pouro Kolata Maoun Wouyene PALE Zogbeanta GOUECKE Dapore Soulouta SOULOUTA Konipara Gouh Nona Banzou Tamoe Kola Kpagalaye Nyenh Koronta Youa Gbouo Kelemanda Zogotta Mahouor Koloda KOBELA KOYAMAH Kpaya Souhoule Kelouenta Poe KOKOTA Filikoele Koola Yleouena Batoata Gbadiou Niambara LOLA SAMOE Niema Komou Niarakpale Gbamba Banota Kpaya YALENZOU Boma Samoe Moata Kounala LOLA CTRE Koule Sud Boma Sud Horoya BOWE NZEREKORE CTRE Dorota Nyalakpale Bangoueta Gonia Nyen Commercial Toulemou Nzerekore Konia Kotozou Wessoua Aviation Mohomuo YOMOU Gbottoye Yalenzou Secteur zaapa Zao Yalenzou Kerema Gbenemou Lomou Centre centre Toulemou POPULATION PAR SOUS-PREFECTURE NZOO Gbenedapah SOUS-PREFECTURE POPULATION 2021 Foromopa BOSSOU Teyeouon Bounouma 27 605 Bounouma Kankore Gouecke 24 056 centre DISTANCES DES DISTRICTS SANITAIRES DE NZEREKORE Kobela 19 080 Centre de santé Distance N’Zérékoré_CS Poste de santé Distance CS_PS Koropara 23 898 KOULE SUD 9KM NYEMA 10 KM Sehipa Koule 23 756 C S SAMOE 12 KM NYAMPARA PELA 9 KM BOUNOUMA Thuo centre -

Guinea : Reference Map of N’Zérékoré Region (As of 17 Fev 2015)

Guinea : Reference Map of N’Zérékoré Region (as of 17 Fev 2015) Banian SENEGAL Albadariah Mamouroudou MALI Djimissala Kobala Centre GUINEA-BISSAU Mognoumadou Morifindou GUINEA Karala Sangardo Linko Sessè Baladou Hérémakono Tininkoro Sirana De Beyla Manfran Silakoro Samala Soromaya Gbodou Sokowoulendou Kabadou Kankoro Tanantou Kerouane Koffra Bokodou Togobala Centre Gbangbadou Koroukorono Korobikoro Koro Benbèya Centre Gbenkoro SIERRA LEONE Kobikoro Firawa Sassèdou Korokoro Frawanidou Sokourala Vassiadou Waro Samarami Worocia Bakokoro Boukorodou Kamala Fassousso Kissidougou Banankoro Bablaro Bagnala Sananko Sorola Famorodou Fermessadou Pompo Damaro Koumandou Samana Deila Diassodou Mangbala Nerewa LIBERIA Beindou Kalidou Fassianso Vaboudou Binemoridou Faïdou Yaradou Bonin Melikonbo Banama Thièwa DjénédouKivia Feredou Yombiro M'Balia Gonkoroma Kemosso Tombadou Bardou Gberékan Sabouya Tèrèdou Bokoni Bolnin Boninfé Soumanso Beindou Bondodou Sasadou Mama Koussankoro Filadou Gnagbèdou Douala Sincy Faréma Sogboro Kobiramadou Nyadou Tinah Sibiribaro Ouyé Allamadou Fouala Regional Capital Bolodou Béindou Touradala Koïko Daway Fodou 1 Dandou Baïdou 1 Kayla Kama Sagnola Dabadou Blassana Kamian Laye Kondiadou Tignèko Kovila Komende Kassadou Solomana Bengoua Poveni Malla Angola Sokodou Niansoumandou Diani District Capital Kokouma Nongoa Koïko Frandou Sinko Ferela Bolodou Famoîla Mandou Moya Koya Nafadji Domba Koberno Mano Kama Baïzéa Vassala Madina Sèmèkoura Bagbé Yendemillimo Kambadou Mohomè Foomè Sondou Diaboîdou Malondou Dabadou Otol Beindou Koindou -

The Woods of Liberia

THE WOODS OF LIBERIA October 1959 No. 2159 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST PRODUCTS LABORATORY FOREST SERVICE MADISON 5, WISCONSIN In Cooperation with the University of Wisconsin THE WOODS OF LIBERIA1 By JEANNETTE M. KRYN, Botanist and E. W. FOBES, Forester Forest Products Laboratory,2 Forest Service U. S. Department of Agriculture - - - - Introduction The forests of Liberia represent a valuable resource to that country-- especially so because they are renewable. Under good management, these forests will continue to supply mankind with products long after mined resources are exhausted. The vast treeless areas elsewhere in Africa give added emphasis to the economic significance of the forests of Liberia and its neighboring countries in West Africa. The mature forests of Liberia are composed entirely of broadleaf or hardwood tree species. These forests probably covered more than 90 percent of the country in the past, but only about one-third is now covered with them. Another one-third is covered with young forests or reproduction referred to as low bush. The mature, or "high," forests are typical of tropical evergreen or rain forests where rainfall exceeds 60 inches per year without pro longed dry periods. Certain species of trees in these forests, such as the cotton tree, are deciduous even when growing in the coastal area of heaviest rainfall, which averages about 190 inches per year. Deciduous species become more prevalent as the rainfall decreases in the interior, where the driest areas average about 70 inches per year. 1The information here reported was prepared in cooperation with the International Cooperation Administration. 2 Maintained at Madison, Wis., in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. -

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens Distributed 1901 - 1990

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens distributed 1901 - 1990 Page 1 - https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/57407494 15 July 1901 Dr T Johnson FLS, Science and Art Museum, Dublin Two cases containing the following:- Ackd 20.7.01 1. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 2. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 3. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 4. Wood of Anogeissus acuminata, Ganjam, Paris Exhibition 1900 5. Wood of Xylia dolabriformis, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 6. Wood of Pterocarpus Marsupium, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 7. Wood of Lagerstremia parviflora, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 8. Wood of Anogeissus latifolia , Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 9. Wood of Gyrocarpus jacquini, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 10. Wood of Acrocarpus fraxinifolium, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 11. Wood of Ulmus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 12. Wood of Phyllanthus emblica, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 13. Wood of Adina cordifolia, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 14. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 15. Wood of Cedrela toona, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 16. Wood of Premna bengalensis, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 17. Wood of Artocarpus chaplasha, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 18. Wood of Artocarpus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 19. Wood of Ulmus wallichiana, N. India, Paris Exhibition 1900 20. Wood of Diospyros kurzii , India, Paris Exhibition 1900 21. Wood of Hardwickia binata, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 22. Flowers of Heterotheca inuloides, Mexico, Paris Exhibition 1900 23. Leaves of Datura Stramonium, Paris Exhibition 1900 24. Plant of Mentha viridis, Paris Exhibition 1900 25. Plant of Monsonia ovata, S. -

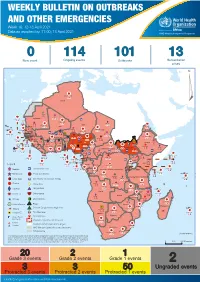

Week 16: 12-18 April 2021

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 16: 12-18 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 18 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 114 101 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 119 642 3 155 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 694 170 Mauritania 7 2 13 070 433 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 129 453 Mali 3 491 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 706 169 Eritrea Cape Verde 39 782 1 091 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 20 466 191 973 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 242 028 3 370 0 164 233 2 061 Guinea 13 129 154 12 38 397 1 3 712 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 61 731 919 52 14 Ghana 5 787 75 Côte d'Ivoire 10 473 114 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 97 17 25 0 21 612 260 45 560 274 91 709 771 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 151 653 2 481 655 2 43 0 119 12 6 1 488 6 4 028 79 12 533 7 259 106 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 378 338 Kenya Legend 7 611 95 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 275 35 23 888 325 Measles 21 858 133 Democratic Republic of the Congo 10 084 137 Burundi 3 612 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 28 956 745 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 190 0 4875 25 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 24 389 561 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 90 918 1 235 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 941 1 138 862 0 3 815 146 Zambia 133 0 Mozambique -

Case Studies on the Status of Invasive Woody Plant Species in the Western Indian Ocean

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Forest Health & Biosecurity Working Papers Case Studies on the Status of Invasive Woody Plant Species in the Western Indian Ocean 1. Synthesis By C. KUEFFER1, P. VOS2, C. LAVERGNE3 and J. MAUREMOOTOO4 1 Geobotanical Institute, ETH (Federal Institute of Technology), Zurich, Switzerland 2 Forestry Section, Ministry of Environment & Natural Resources, Seychelles 3 Conservatoire Botanique National de Mascarin, Réunion 4 Mauritian Wildlife Foundation, Mauritius May 2004 Forest Resources Development Service Working Paper FBS/4-1E Forest Resources Division FAO, Rome, Italy Disclaimer The FAO Forestry Department Working Papers report on issues and activities related to the conservation, sustainable use and management of forest resources. The purpose of these papers is to provide early information on on-going activities and programmes, and to stimulate discussion. This paper is one of a series of FAO documents on forestry-related health and biosecurity issues. The study was carried out from November 2002 to May 2003, and was financially supported by a special contribution of the FAO-Netherlands Partnership Programme on Agro-Biodiversity. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Quantitative information regarding the status of forest resources has been compiled according to sources, methodologies and protocols identified and selected by the authors, for assessing the diversity and status of forest resources. -

Reproductive Biology of <I>Pentadesma

Plant Ecology and Evolution 148 (2): 213–228, 2015 http://dx.doi.org/10.5091/plecevo.2015.998 REGULAR PAPER Reproductive biology of Pentadesma butyracea (Clusiaceae), source of a valuable non timber forest product in Benin Eben-Ezer B.K. Ewédjè1,2,*, Adam Ahanchédé3, Olivier J. Hardy1 & Alexandra C. Ley1,4 1Service Evolution Biologique et Ecologie, Faculté des Sciences, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 50 Av. F. Roosevelt, 1050 Brussels, Belgium 2Faculté des Sciences et Techniques FAST-Dassa, BP 14, Dassa-Zoumé, Université d’Abomey-Calavi, Benin 3Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques FSA, BP526, Université d’Abomey-Calavi, Benin 4Institut für Geobotanik und Botanischer Garten, University Halle-Wittenberg, Neuwerk 21, 06108 Halle (Saale), Germany *Author for correspondence: [email protected] Background and aims – The main reproductive traits of the native African food tree species, Pentadesma butyracea Sabine (Clusiaceae), which is threatened in Benin and Togo, were examined in Benin to gather basic data necessary to develop conservation strategies in these countries. Methodology – Data were collected on phenological pattern, floral morphology, pollinator assemblage, seed production and germination conditions on 77 adult individuals from three natural populations occurring in the Sudanian phytogeographical zone. Key results – In Benin, Pentadesma butyracea flowers once a year during the dry season from September to December. Flowering entry displayed less variation among populations than among individuals within populations. However, a high synchrony of different floral stages between trees due to a long flowering period (c. 2 months per tree), might still facilitate pollen exchange. Pollen-ovule ratio was 577 ± 213 suggesting facultative xenogamy. The apical position of inflorescences, the yellowish to white greenish flowers and the high quantity of pollen and nectar per flower (1042 ± 117 µL) represent floral attractants that predispose the species to animal-pollination. -

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. Map of Guinea1 1 For the purposes of this report, we will be using the following names for the regions of Guinea: Upper Guinea, Middle Guinea, Lower Guinea, and the Forest Region. Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5188 Fax (404) 420-5196 www.cartercenter.org The Carter Center Contents Foreword ..................................1 Proxy Voting and Participation of Executive Summary .........................2 Marginalized Groups ......................43 The Carter Center Election Access for Domestic Observers and Observation Mission in Guinea ...............5 Party Representatives ......................44 The Story of the Guinean Security ................................45 Presidential Elections ........................8 Closing and Counting ......................46 Electoral History and Political Background Tabulation .............................48 Before 2008 ..............................8 Election Dispute Resolution and the From the CNDD Regime to the Results Process ...........................51 Transition Period ..........................9 Disputes Regarding First-Round Results ........53 Chronology of the First and Disputes Regarding Second-Round Results ......54 Second Rounds ...........................10 Conclusion and Recommendations for Electoral Institutions and the Framework for the Future Elections ...........................57 -

Chemical Characterization of Shea Butter Oil Soap (Butyrospermum Parkii G

International Journal of Development and Sustainability ISSN: 2186-8662 – www.isdsnet.com/ijds Volume 6 Number 10 (2017): Pages 1282-1292 ISDS Article ID: IJDS13022701 Chemical characterization of shea butter oil soap (Butyrospermum parkii G. Don) K.O. Boadu 1*, M.A. Anang 1, S.K. Kyei 2 1 Industrial Chemistry Unit, Department of Chemistry, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana 2 Department of Chemical Engineering, Kumasi Technical University, Kumasi, Ghana Abstract Shea butter oil was obtained from the edible nut of the fruit from Karite (Butyrospermum parkii) tree grown in Savannah Grasslands of West Africa. It is a wild growing tree that produces tiny, almond-like fruit. Shea Butter oil was extracted from the fruit by cold process and was used to prepare medical soap. Chemical analysis showed that the obtained soap has 76.0 %, 9.0 %, 3.41 minutes, 9.0, 0.0 %, 3.7% and 0.87 as its total fatty matter, moisture, foam stability, pH, free caustic alkali, unsaponified and specific gravity respectively. Due to the phytoconstituents in shea butter oil and the favourable chemical characteristics of the soap, it can be used as medical and cosmetics toilet soap. Such soap is used to alleviate problems of the skin and scalp. Keywords: Medical Soap; Karite Tree; Butyrospermum Parkii; Shea Butter Oil; Chemical Characteristics Published by ISDS LLC, Japan | Copyright © 2017 by the Author(s) | This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Cite this article as: Boadu, K.O., Anang, M.A. -

Natural Cosmetic Ingredients Exotic Butters & Oleins

www.icsc.dk Natural Cosmetic Ingredients Exotic Butters & Oleins Conventional, Organic and Internal Stabilized Exotic Butters & Oleins Exotic Oils and butters are derived from uncontrolled plantations or jungles of Asia, Africa and South – Central America. The word exotic is used to define clearly that these crops are dependent on geographical and seasonal variations, which has an impact on their yearly production capacity. Our selection of natural exotic butters and oils are great to be used in the following applications: Anti-aging and anti-wrinkle creams Sun Protection Factor SPF Softening and hydration creams Skin brightening applications General skin care products Internal Stabilization I.S. extends the lifecycle of the products 20-30 times as compare to conventional. www.icsc.dk COCOA BUTTER Theobroma Cacao • Emollient • Stable emulsions and exceptionally good oxidative stability • Reduce degeneration and restores flexibility of the skin • Fine softening effect • Skincare, massage, cream, make-up, sunscreens CONVENTIONAL ORGANIC STABILIZED AVOCADO BUTTER Persea Gratissima • Skincare, massage, cream, make-up • Gives stables emulsions • Rapid absorption into skin • Good oxidative stability • High Oleic acid content • Protective effect against sunlight • Used as a remedy against rheumatism and epidermal pains • Emollient CONVENTIONAL ORGANIC STABILIZED ILLIPE BUTTER Shorea Stenoptera • Emollient • Fine softening effect and good spreadability on the skin • Stable emulsions and exceptionally good oxidative stability • Creams, stick -

Improving Sustainable Water Access in Rural Communities in Guinea

© CEAD 2016 IMPROVING SUSTAINABLE WATER ACCESS IN RURAL COMMUNITIES IN GUINEA OCTOBER 2018 Overview The Ebola outbreak of 2014-2016 highlighted the need to strengthen water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) health-related preventive measures at all levels in Guinea. Safe drinking water and adequate sanitation are essential for life and health. A sustainable supply of safe water, adequate sanitation and improved hygiene not only saves lives, but also has significant effects for girls and women, who bear primary responsibility for fetching water, which is often unclean and far from home. This daily chore exposes them to the potential risk of violence and can prevent girls from attending school. UNICEF believes that access to WASH goes far beyond health improvements, positively affecting areas such as human rights, girls’ education, gender relations and nutrition. In 2000, approximately 47 percent of the population in rural Guinea consumed contaminated water, further increasing the risk of communicable diseases; the success of the manual drilling project supported by your previous gift has helped bring that percentage down by 2015 to 32 percent.1 Still, rural communities remain poorly served with too few sources of safe water in areas that are too widely spaced apart. UNICEF estimates that at approximately 10,154 water points are required to meet to the country’s basic water supply needs. And although the number of people sharing a water point should only be 300, data collected by the national water service agency (Service National d’Aménagement des Points d’Eau, or SNAPE) shows that an average of 1,500 people in fact share the same water point. -

Ethnobotany of Pentadesma Butyracea in Benin: a Quantitative Approach C

Ethnobotany of Pentadesma butyracea in Benin: A quantitative approach C. Avocèvou-Ayisso, T.H. Avohou, M. Oumorou, G. Dossou and B. Sinsin Research Abstract Integrating ethnobotanical knowledge in the development guistiques de deux zones géographiques distinctes of management and conservation strategies of indigenous du Bénin, et comment ces variations pourraient in- plant resources is critical to their effectiveness. In this pa- fluencer les stratégies de conservation de l’espèce. per, we used four plant use indices to assess how the Sept groupes sociolinguistiques à savoir les Anii, Na- plant use knowledge of a multipurpose tree (Pentadesma got, Kotocoli, et Fulani au centre, et les Waama, Dita- butyracea Sabine) varies across different sociolinguistic mari et Natimba au nord-ouest du pays, ont été con- groups from two geographical areas of Benin, and how sidérés. Quatre valeurs d’usage à savoir le nombre these variations may influence the species’ conservation d’usages rapportés par organe de la plante, la valeur and utilisation strategies. Seven sociolinguistic groups de l’organe en question, des usages spécifiques et la namely the Anii, Nagot, Kotocoli, and Fulani in the central valeur d’usage intraspécifique ont été calculées pour part, and the Waama, Ditamari and Natimba in the north- chaque groupe. Les diverses communautés ont mon- western part of the country were considered. We deter- tré des intérêts différents pour les divers organes de mined the reported use value of the plant parts, the plant l’espèce utilisés. Les Nagot ont présenté le meilleur part value, the specific use and the intraspecific use value niveau de connaissances de P.