Key Considerations: 2021 Outbreak of Ebola in Guinea, the Context of N’Zérékoré

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUINEE - PREFECTURE DE NZEREKORE Carte De La Population Et Des Structures Sanitaires 10 Mars 2021

GUINEE - PREFECTURE DE NZEREKORE Carte de la population et des structures sanitaires 10 mars 2021 BEYLA KOUANKAN BOOLA Boola Kognea Maghana Lomou Ouinzou Kogbata FOUMBADOU SEREDOU Boma Nord Gbana KOROPARA Lomou Gounangalaye Saouro Kpamou Koni Koropara Lokooua Alaminata Foozou Nyema Nord Kabieta Bassa´ta Koroh Keleta Ouleouon WOMEY Pampara Suobaya Bowe Nord NZEBELA Keorah Womey kerezaghaye Zenemouta Beneouli Selo MACENTA Loula Yomata Koule Komata KOULE Pale Yalakpala Tokpata Goueke Voumou LAINE Tamoe Niaragbaleye Kpoulo Pouro Kolata Maoun Wouyene PALE Zogbeanta GOUECKE Dapore Soulouta SOULOUTA Konipara Gouh Nona Banzou Tamoe Kola Kpagalaye Nyenh Koronta Youa Gbouo Kelemanda Zogotta Mahouor Koloda KOBELA KOYAMAH Kpaya Souhoule Kelouenta Poe KOKOTA Filikoele Koola Yleouena Batoata Gbadiou Niambara LOLA SAMOE Niema Komou Niarakpale Gbamba Banota Kpaya YALENZOU Boma Samoe Moata Kounala LOLA CTRE Koule Sud Boma Sud Horoya BOWE NZEREKORE CTRE Dorota Nyalakpale Bangoueta Gonia Nyen Commercial Toulemou Nzerekore Konia Kotozou Wessoua Aviation Mohomuo YOMOU Gbottoye Yalenzou Secteur zaapa Zao Yalenzou Kerema Gbenemou Lomou Centre centre Toulemou POPULATION PAR SOUS-PREFECTURE NZOO Gbenedapah SOUS-PREFECTURE POPULATION 2021 Foromopa BOSSOU Teyeouon Bounouma 27 605 Bounouma Kankore Gouecke 24 056 centre DISTANCES DES DISTRICTS SANITAIRES DE NZEREKORE Kobela 19 080 Centre de santé Distance N’Zérékoré_CS Poste de santé Distance CS_PS Koropara 23 898 KOULE SUD 9KM NYEMA 10 KM Sehipa Koule 23 756 C S SAMOE 12 KM NYAMPARA PELA 9 KM BOUNOUMA Thuo centre -

Guinea : Reference Map of N’Zérékoré Region (As of 17 Fev 2015)

Guinea : Reference Map of N’Zérékoré Region (as of 17 Fev 2015) Banian SENEGAL Albadariah Mamouroudou MALI Djimissala Kobala Centre GUINEA-BISSAU Mognoumadou Morifindou GUINEA Karala Sangardo Linko Sessè Baladou Hérémakono Tininkoro Sirana De Beyla Manfran Silakoro Samala Soromaya Gbodou Sokowoulendou Kabadou Kankoro Tanantou Kerouane Koffra Bokodou Togobala Centre Gbangbadou Koroukorono Korobikoro Koro Benbèya Centre Gbenkoro SIERRA LEONE Kobikoro Firawa Sassèdou Korokoro Frawanidou Sokourala Vassiadou Waro Samarami Worocia Bakokoro Boukorodou Kamala Fassousso Kissidougou Banankoro Bablaro Bagnala Sananko Sorola Famorodou Fermessadou Pompo Damaro Koumandou Samana Deila Diassodou Mangbala Nerewa LIBERIA Beindou Kalidou Fassianso Vaboudou Binemoridou Faïdou Yaradou Bonin Melikonbo Banama Thièwa DjénédouKivia Feredou Yombiro M'Balia Gonkoroma Kemosso Tombadou Bardou Gberékan Sabouya Tèrèdou Bokoni Bolnin Boninfé Soumanso Beindou Bondodou Sasadou Mama Koussankoro Filadou Gnagbèdou Douala Sincy Faréma Sogboro Kobiramadou Nyadou Tinah Sibiribaro Ouyé Allamadou Fouala Regional Capital Bolodou Béindou Touradala Koïko Daway Fodou 1 Dandou Baïdou 1 Kayla Kama Sagnola Dabadou Blassana Kamian Laye Kondiadou Tignèko Kovila Komende Kassadou Solomana Bengoua Poveni Malla Angola Sokodou Niansoumandou Diani District Capital Kokouma Nongoa Koïko Frandou Sinko Ferela Bolodou Famoîla Mandou Moya Koya Nafadji Domba Koberno Mano Kama Baïzéa Vassala Madina Sèmèkoura Bagbé Yendemillimo Kambadou Mohomè Foomè Sondou Diaboîdou Malondou Dabadou Otol Beindou Koindou -

PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II

OFFICIAL USE ONLY IDA/SecM2007-0684 December 12, 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized For meeting of Board: Tuesday, January 8, 2008 FROM: Vice President and Corporate Secretary Guinea: Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper and Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note 1. Attached is the Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II. The IMF is currently scheduled to discuss this document on December 21, 2007. 2. The PRSP II was prepared by the Government of Guinea. The paper acknowledges the disappointing outcome of the first PRSP, which covered the period 2002-2006. The political, social and economic environment in which the implementation of PRSP I took place was characterized by poor governance, political instability, and low growth which led to an increase in poverty from 49 percent in 2002 to an estimated 54 percent in 2005. Overall, public service delivery deteriorated in terms of both quality and access and the living conditions for most Guineans worsened. Public Disclosure Authorized 3. PRSP II aims at recapturing lost ground over the past five years. The overall strategy is based on three pillars: (i) improving governance; (ii) accelerating growth and increasing employment opportunities; and (iii) improving access to basic services. It focuses on restoring macroeconomic stability, institutional and structural reforms, and mechanisms to strengthen the democratic process implementation capacity. 4. As approved by the Board on August 6, 2007, the pilot Board Technical Questions and Answer Database (http://boardqa.worldbank.org or from the EDs' portal) is now open for questions. -

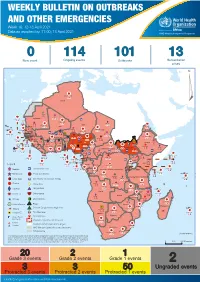

Week 16: 12-18 April 2021

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 16: 12-18 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 18 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 114 101 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 119 642 3 155 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 694 170 Mauritania 7 2 13 070 433 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 129 453 Mali 3 491 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 706 169 Eritrea Cape Verde 39 782 1 091 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 20 466 191 973 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 242 028 3 370 0 164 233 2 061 Guinea 13 129 154 12 38 397 1 3 712 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 61 731 919 52 14 Ghana 5 787 75 Côte d'Ivoire 10 473 114 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 97 17 25 0 21 612 260 45 560 274 91 709 771 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 151 653 2 481 655 2 43 0 119 12 6 1 488 6 4 028 79 12 533 7 259 106 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 378 338 Kenya Legend 7 611 95 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 275 35 23 888 325 Measles 21 858 133 Democratic Republic of the Congo 10 084 137 Burundi 3 612 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 28 956 745 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 190 0 4875 25 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 24 389 561 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 90 918 1 235 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 941 1 138 862 0 3 815 146 Zambia 133 0 Mozambique -

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. Map of Guinea1 1 For the purposes of this report, we will be using the following names for the regions of Guinea: Upper Guinea, Middle Guinea, Lower Guinea, and the Forest Region. Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5188 Fax (404) 420-5196 www.cartercenter.org The Carter Center Contents Foreword ..................................1 Proxy Voting and Participation of Executive Summary .........................2 Marginalized Groups ......................43 The Carter Center Election Access for Domestic Observers and Observation Mission in Guinea ...............5 Party Representatives ......................44 The Story of the Guinean Security ................................45 Presidential Elections ........................8 Closing and Counting ......................46 Electoral History and Political Background Tabulation .............................48 Before 2008 ..............................8 Election Dispute Resolution and the From the CNDD Regime to the Results Process ...........................51 Transition Period ..........................9 Disputes Regarding First-Round Results ........53 Chronology of the First and Disputes Regarding Second-Round Results ......54 Second Rounds ...........................10 Conclusion and Recommendations for Electoral Institutions and the Framework for the Future Elections ...........................57 -

Guinea Ebola Response International Organization for Migration

GUINEA EBOLA RESPONSE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION SITUATION REPORT From 9 to 31 May, 2016 First simulation exercise to manage EVD cases at the Point of Entry of Madina Oula, at the border with Sierra Leone. News © IOM Guinea 2016 Between May 9 and 13, IOM, in partnership with On the 12 May, IOM organized a On the 14 May, in partnership with CDC, launched the first simulation exercise to manage groundbreaking ceremony at the Tamaransy International Medical Corps (IMC), IOM EVD cases at the Madina Oula Point of Entry (PoE), at market, a village in Boké Prefecture that was officially launched Community Event-Based the border with Sierra Leone. Between May 22 and heavily affected by EVD. This activity is part of Surveillance (CEBS) in the prefecture of 26, it launched the second simulation exercise at the IOM’s support to the Guinean Government in Kindia. Many prefectural health and PoE of Baala, near Liberia. The main objective of these the socio-economic recovery of Ebola administrative authorities participated in the exercises is to prepare the authorities in charge of the Survivors. ceremony, during which bicycles and two points of entry in detecting, notifying and managing motorcycles were distributed to community any suspected case of potential epidemic disease, health agents and their supervisors. especially EVD cases at their various borders. Epidemiological situation On 29 March 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the end of EVD in West Africa as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. In its situation report of 26 May 2016, WHO underlined that the latest notified case in Guinea during the resurgence of Ebola in mid-March was declared Ebola negative for the second time in a row after final testing on 19 April, 2016. -

A Methodology for Complex Agricultural Development Projects

Systemic Impact Evaluation: A Methodology for Complex Agricultural Development Projects. The Case of a Contract Farming Project in Guinea Jocelyne Delarue, Hubert Cochet To cite this version: Jocelyne Delarue, Hubert Cochet. Systemic Impact Evaluation: A Methodology for Complex Agri- cultural Development Projects. The Case of a Contract Farming Project in Guinea. The European Journal of Development Research, 2013, 25 (5), p.778-796. 10.1057/ejdr.2013.15. halshs-01374496 HAL Id: halshs-01374496 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01374496 Submitted on 7 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Original Article Systemic Impact Evaluation: A Methodology for Complex Agricultural Development Projects. The Case of a Contract Farming Project in Guinea Jocelyne Delaruea and Hubert Cochetb aAgence Française de Développement, Evaluation and Capitalization Unit, Paris, France. E-mail: [email protected] bAgro Paris Tech, Comparative Agriculture and Agricultural Development Research Unit, Paris, France. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article presents a mixed-method approach used to analyse the impact of a complex agricultural development project, the SOGUIPAH (Guinean Oil Palms and Rubber Company) project designed to promote oil palm and rubber cultivation in Guinea. -

Improving Sustainable Water Access in Rural Communities in Guinea

© CEAD 2016 IMPROVING SUSTAINABLE WATER ACCESS IN RURAL COMMUNITIES IN GUINEA OCTOBER 2018 Overview The Ebola outbreak of 2014-2016 highlighted the need to strengthen water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) health-related preventive measures at all levels in Guinea. Safe drinking water and adequate sanitation are essential for life and health. A sustainable supply of safe water, adequate sanitation and improved hygiene not only saves lives, but also has significant effects for girls and women, who bear primary responsibility for fetching water, which is often unclean and far from home. This daily chore exposes them to the potential risk of violence and can prevent girls from attending school. UNICEF believes that access to WASH goes far beyond health improvements, positively affecting areas such as human rights, girls’ education, gender relations and nutrition. In 2000, approximately 47 percent of the population in rural Guinea consumed contaminated water, further increasing the risk of communicable diseases; the success of the manual drilling project supported by your previous gift has helped bring that percentage down by 2015 to 32 percent.1 Still, rural communities remain poorly served with too few sources of safe water in areas that are too widely spaced apart. UNICEF estimates that at approximately 10,154 water points are required to meet to the country’s basic water supply needs. And although the number of people sharing a water point should only be 300, data collected by the national water service agency (Service National d’Aménagement des Points d’Eau, or SNAPE) shows that an average of 1,500 people in fact share the same water point. -

Interim Report Government of Japan COUNTERING EPIDEMIC-PRONE

Government of Japan COUNTERING EPIDEMIC-PRONE DISEASES ALONG BORDERS AND MIGRATION ROUTE IN GUINEA Interim Report Project Period: 30 March 2016 – 29 March 2017 Reporting Period: 30 March 2016-31 August 2016 Funds: 2.000.000 USD Executing Organization: International Organization for Migration (IOM) Guinea October 2016 Interim Report to Government of Japan COUNTERING EPIDEMIC-PRONE DISEASES ALONG BORDERS AND MIGRATION ROUTES IN GUINEA Project Data Table Executing Organization: International Organization for Migration (IOM) Project Identification and IOM Project Code: MP.0281 Contract Numbers: Contract number: NI/IOM/120 Project Management Site Management Site: Conakry, CO, GUINEA and Relevant Regional Regional Office: Dakar, RO, SENEGAL Office: Project Period: 30 March 2016 – 29 March 2017 Geographical Coverage: Guinea Communal / Sub Prefectural / Prefectural / Regional Health authorities and Project Beneficiaries: Community members in Guinea Ministry of Health, National Health Security Agency, US Agency for international development (USAID), U.S. Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance Project Partner(s): (OFDA), Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), International Medical Corps (IMC), Research triangle institute (RTI), Premieres Urgences (PU) Reporting Period: 30 March 2016 – 31 August 2017 Date of Submission: 30 October 2016 Total Confirmed 2,000,000 USD Funding: Total Funds Received to 2,000,000 USD Date: Total Expenditures: 439,761 USD Headquarters 17 route des Morillons • C.P. 71 • CH-1211 -

Elements De La Carte Sanitaire Des Etablissements De Soins Du Secteur Public

REPUBLIQUE DE GUINEE ----------------- Travail - Justice - Solidarité MINISTERE DE LA SANTE PUBLIQUE ELEMENTS DE LA CARTE SANITAIRE DES ETABLISSEMENTS DE SOINS DU SECTEUR PUBLIC JANVIER 2012 TABLE DES MATIERES CHAPITRE I : SITUATION ACTUELLE DES ETABL ISSEMENTS DE SOINS ............................................. 4 I - TYPOLOGIE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 II - NIVEAU PRIMAIRE ............................................................................................................................................ 4 III - NIVEAU SECONDAIRE ..................................................................................................................................... 7 IV - NIVEAU TERTIAIRE ........................................................................................................................................ 10 V - POINTS FAIBLES .............................................................................................................................................. 12 VI - POINTS FORTS ................................................................................................................................................ 13 VII - CONTRAINTES ............................................................................................................................................... 13 VIII - OPPORTUNITES ET MENACES .................................................................................................................. -

Non-Wood Forest Products and Services for Socio-Economic Development

Non-Wood Forest Products and Services for Socio-Economic Development The AFRICAN FOREST FORUM – a platform for stakeholders in African Forestry A Compendium for Technical and Professional Forestry Education Suzana Agustino, Bennet Mataya, Kingiri Senelwa & Enoch G. Achigan-Dako Non-Wood Forest Products and Services for Socio-Economic Development © African Forest Forum 2011 All rights reserved African Forest Forum c/o World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) P.O. Box 30677-00100 Nairobi KENYA Tel: +254 20 722 4203 Fax: +254 20 722 4001 www.afforum.org Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the African Forest Forum concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries regarding its economic system or degree of development. Excerpts may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the African Forest Forum. Correct citation: Agustino, S., Mataya, B., Senelwa, K., and Achigan-Dako, G.E. 2011. Non-wood forest products and services for socio-economic development. A Compendium for Technical and Professional Forestry Education. The African Forest Forum, Nairobi, Kenya. 219 pp. Printed in Nairobi in 2011. ISBN 978-92-9059-294-5. Non-Wood Forest Products and Services for Socio-Economic Development A Compendium for Technical and Professional Forestry Education Suzana Agustino Bennet Mataya Kingiri Senelwa Enoch G. Achigan-Dako The African Forest Forum (AFF) NON-WOOD FOREST PRODUCTS AND SERVICES FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Table of Contents List of Figures, Tables and Boxes vi Acronymns and Abbreviations viii Foreword xi Concepts, Values and Uses of Non-Wood Forest Products and Services 1 1.1. -

Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper PRSP–2

© 2008 International Monetary Fund January 2008 IMF Country Report No. 08/7 Guinea: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) are prepared by member countries in broad consultation with stakeholders and development partners, including the staffs of the World Bank and the IMF. Updated every three years with annual progress reports, they describe the country's macroeconomic, structural, and social policies in support of growth and poverty reduction, as well as associated external financing needs and major sources of financing. This country document for Guinea, dated August 2007, is being made available on the IMF website by agreement with the member country as a service to users of the IMF website. To assist the IMF in evaluating the publication policy, reader comments are invited and may be sent by e-mail to [email protected]. Copies of this report are available to the public from International Monetary Fund • Publication Services 700 19th Street, N.W. • Washington, D.C. 20431 Telephone: (202) 623-7430 • Telefax: (202) 623-7201 E-mail: [email protected] • Internet: http://www.imf.org Price: $18.00 a copy International Monetary Fund Washington, D.C. ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution This page intentionally left blank ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution REPUBLIC OF GUINEA Work – Justice – Solidarity Ministry of the Economy, Finances and Planning Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper PRSP–2 (2007–2010) Conakry, August 2007 Permanent Secretariat for the Poverty Reduction Strategy (SP-SRP) Website: www.srp-guinee.org.Telephone: (00224) 30 43 10 80. ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document is the fruit of a collective effort that has involved many development stakeholders: executives of regionalized and decentralized structures, civil society organizations, development partners, etc.